The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. | I.14.9 |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I.14.9

CONFIRMING EVIDENCE:

THE PALACE GROUNDS AT AACHEN

We do not know whether or to what extent, if ever, the

modular construction methods used on the Plan of St. Gall

were implemented in any of the larger monasteries built or

rebuilt during the reign of Louis the Pious. But one other

site, a physical and historical reality, can be said to have

been organized along similar lines: Charlemagne's Palace

at Aachen. While Ernest Born and I were working on the

Plan of St. Gall, Leo Hugot of Aachen made a meticulous

dimensional survey of the palace grounds and its buildings.

None knew of the other's work, which was simultaneously

and for the first time displayed in 1965 at the Council of

Europe Exhibition Karl der Grosse in Aachen, each in the

form of a model, together with two brief explanatory statements

that formed part of the official Exhibition Catalogue.[387]

Charlemagne's Palace at Aachen was established on the

ground of an old Roman settlement that—like most other

Roman provincial towns or military camps—was inscribed

into a large rectangle, internally divided into four equal

quarters by two streets intersecting each other at right

angles, conditions that are even today mirrored in the

course of certain streets of the city of Aachen (fig. 71.X).

In the southeast corner of that rectangle were the famous

hot springs, the amenities of which were one of the primary

reasons for the selection of this site as the first "permanent"

residence of the great ruler. In laying out his residence,

Charlemagne did not follow the Roman dispositions

blindly. He changed the alignment of his buildings so that

the axis of the Palace Chapel would run from west to east,

as the liturgy demanded, and since all of the other buildings

of the Palace were either parallel or at right angles to the

church, this system of building came to lie athwart, at an

angle of 38 degrees, the Roman street system. As the

Romans had done with their settlement, so Charlemagne

also inscribed his residence and its buildings into an area

of rectangular shape (fig. 71.Y). In laying out his grounds

he availed himself, as the dimensional survey of the site by

Leo Hugot shows, of a modular base value consisting of a

rod 12 feet long. He placed the Palace Chapel (fig. 71.Y, 1)

against the southern edge, the Audience Hall (fig. 71.Y, 5)

against the northern edge of a large open square, each side

of which had a length of 30 rods = 360 feet. Internally

this square was composed of 16 smaller modules, each of

which formed an equilateral square of 7 rods = 84 feet.

The Palace grounds were intersected by two streets which

crossed each other at right angles dividing the site into an

outer and an inner court. These streets were each 2 rods

broad = 24 feet, bringing each side of the square to a total

of 30 rods = 360 feet. Hugot's analysis of the square grid

of the Palace grounds (Hugot, 1965, fig. 2 facing p. 524)

(fig. 71.Y, 5) or the site of the southern annex to the Palace

Chapel; the so-called Secretarium (fig. 71.Y, 4). Ernest

Born's analysis, superimposed in red on Hugot's plan

shows that with these two buildings included, the whole of

the Palace grounds could be conceived as being inscribed

into a rectangle, measuring 30 rods in width (30 × 12 =

360 feet) and 52 rods in length (52 × 12 = 624 feet). He

emphasizes in his caption to fig. 71.Y the importance of the

use of the sacred numbers 3, 4, 10, 12, 30 and 40 in the

construction of this grid.

The proportions of the Palace Chapel, Hugot's analysis

has shown, were as carefully and consistently regulated as

the layout of the entire Palace grounds (figs. 71.Za, b, c).

The base module, again, is a rod 12 feet long. The chapel

itself was fitted into a square, each side of which measured

84 feet = 7 rods (fig. 71.Za). To this cube was added in the

east a choir 24 feet deep (2 rods), and on the entrance side

a westwork of identical depth. In the vertical plane the

84-foot cube reaches from ground floor to base of the

pyramid. The total elevation is composed of: height of

outer wall, 48 feet (4 rods); height of gallery roof, 12 feet

(1 rod); height of drum, 24 feet (2 rods).

The height of the pyramidal roof of the octagon, in this

context (the original pyramid has disappeared) can only

have measured 2 rods = 24 feet. The total height from the

ground to the apex of the structure, accordingly would be

9 rods = 108 feet.

This is not the time to go into the structural aesthetics of

this important building.[388]

But I cannot forego the pleasure

of remarking on the implications Hugot's findings had with

regard to our own work. First of all, it removed whatever

residual doubt Ernest Born and I may still have entertained

concerning the correctness of our interpretation of the Plan

of St. Gall. Second, it added new weight to the arguments

which we have advanced in a preceding chapter concerning

the provenance of the original scheme from sources close

to the Court School as well as to Bishop Hildebold, the

titular head of that school (791-819).

Bishop Hildebold's church at Cologne, as has been shown

in a preceding chapter, served as model for the Church of

the Plan of St. Gall.[389]

The site organization methods, which

Leo Hugot has shown were used for the Palace of Aachen,

are greatly akin in spirit to those which we have shown to

have been used in the layout of the Plan of St. Gall. This

kinship suggests that the designer of the latter was not only

familiar with, but in all likelihood inspired by the former.

He might even have had access to the original drawings

used for the Palace grounds and its buildings.

The importance of Leo Hugot's findings about the

modular construction methods used in the layout of

Charlemagne's Palace at Aachen can hardly be overemphasized.

It is here for the first time in the history of

medieval (and possibly Western) architecture and site

organization that not only the grounds, but also the most

important building on these grounds, the Palace Chapel,

are controlled by a binding and all-pervasive rule of modular

prime relationships. We shall return to this problem

later on in a discussion of the possible historical roots of

this concept.[390]

AACHEN, PALACE CHAPEL. TRIBUNE

DETAIL, BRONZE RAILING, CA. 800

Eight such railings, each 4 feet high and nearly 14 feet long, were each cast in one piece:

an astonishing accomplishment of the Carolingian Renaissance. Roman grille work patterns,

Byzantine acanthus leaves, and Hiberno-Saxon scroll-and-grid motifs are subsumed in

a sophisticated medieval linearism.

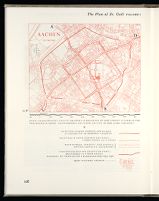

71.X AACHEN: THE CITY CENTER. A CADASTRAL PLAN AFTER 1800 WITH

CHARLEMAGNE'S PALACE GROUNDS

Superimposed in red are the grounds and buildings of Charlemagne's Palace as well as the reconstructed street

system of the Roman town of Aquae Granis (redrawn in part by Ernest Born, after Hugot, 1965, fig. 1 facing

p. 534, and with the aid of Hugot's original drawing which he generously made available to us for that

purpose).

Like most Roman towns or military camps this settlement was internally divided into four quarters by two

main arterials intersecting each other at right angles. The course of these, as Leo Hugot has shown, are

recognizable in the street alignment of the modern city of Aachen. They are: from north to south, the

alignment Kockerell Strasse—Klostergasse and Kleine Marschier Strasse (A-B); from west to east, the

alignment Jakob Strasse and Grosse Koln-Strasse (C-D). The latter was part of a Roman road that led from

Herleen to Kornelismünster into the Eifel Mountains; the former of a road that connected Liège with Julich

and Cologne.

The city of Aachen (French: Aix-la-Chapelle; Italian: Aquisgrana) owes its name to a Celtic settlement and

sanctuary that had sprung up in the vicinity of a cluster of sulphur hot springs which the Romans after their

conquest of this territory, in the first century A.D. converted into a watering place for legionaries, pensioners,

and other civilians visiting or settling there for recreational purposes or for reasons of health. The Romans

referred to this location as Aquae Granis = "the Waters of Granus" (a Celtic deity worshipped in connection

with hot springs). In ancient times, as well as in the Middle Ages and up to our own days, this kind of spring

was believed to have a curative effect on such afflictions as gout, arthritis and scrofula.

At the collapse of the Roman empire the city of Aquae Granis was destroyed (presumably around 375) but the

life of the native population appears to have continued. King Pepin bathed in the springs of Aachen in 765

and ordered the baths to be cleaned. Charlemagne signed deeds in AQUIS PALATIO PUBLICO in 768 and 769,

and between 777 and 786 rebuilt and enlarged his father's palace. The site became his favourite winter

residence from 794 onwards, a date which marks the turning point from ambulant government to rule from a

central seat of government, at least during the winter months, the summers continuing to be taken up by

warfare. Charlemagne furnished the site with a royal Audience Hall and a monumental Palace Chapel (fig.

71.Z), a residence for himself (location and details of construction unknown) as well as a considerable number

of lesser buildings to house his court as well as his bodyguards.

The Palace, as was to be expected, gave rise to the growth of a vast cluster of subsidiary establishments,

mainly to the north and to the west of the royal court, and acquired the appearance of the town when all of

these VICI, together with the Palace, were surrounded in 1172-1176 with a wall by order of Emperor Frederic

Barbarossa.

71.Y SITE PLAN OF THE EMPEROR'S AUDIENCE HALL AND THE PALACE CHAPEL AT AACHEN,

BUILT BETWEEN 796 and 804

KEY TO NUMBERS OF PLAN

1. THE PALACE CHAPEL

2. ATRIUM

3. NORTHERN ANNEX

Metatorium where the emperor changed his attire before entering the chapel

4. SOUTHERN ANNEX

Secretarium for assembly of the clergy and the holding of synods in contemporary sources referred to as In Laterano

5. THE EMPEROR'S AUDIENCE HALL

6. ENTRANCE HALL at ground level connects the OUTER COURT with the INNER COURT

7. BARRACKS for the emperor's guard

Superimposed on Hugot's drawing of a part of the Emperor's Palace at Aachen is shown the rectangular schematism on which its plan is

based. The basic module, as Hugot's dimensional survey of the site has demonstrated, measures 12 feet. Seven basic modules comprise one

major unit. The length of the plan is 7 major units, plus 2 basic modules for the east-west street, plus 1 basic unit for the projection of the

north apse of the Emperor's Audience Hall. Thus the length of the rectangle is 7 × 7 plus 3 units, or 52 units; its width is 4 × 7 units plus

2 units, or 30 units—a rectangle 624 feet long by 360 feet wide.

What captures our attention is the prevailing scheme of numerical and space relationships. The sacred numbers 3, 4, and 7, with 10, 12,

and 40, represent values of measurement that govern or control lines and critical grid relationships and are suffused into the fabric of the

plan to form interrelated kinships. For example, the length of the plan, 52 units, saturated with 75 [(7 × 7) + 3] is the sum of 40 plus 12.

The width of the plan, 30 units, is the product of 3 × 10 and, with 12 as a multiplier, creates 360 feet [(3 + 3 + 3) × 40]. Such a collection

of NUMERI SACRI offers striking evidence of the presence of sacred numbers as a dominating influence in the mind of the Carolingian

planner at the heart of the Empire, at this period in the development of western civilization. The aesthetic consequences of this pervasive

geometric and numerical schematism is another and different problem. Too, it is not without interest that the 3-4-5 triangular relationship

for the formation of a right angle is consonant with the 12-foot grid and would facilitate, in the field, layout for building foundations. In

monumental building schemes in particular, and all building in general, this would be advantageous to both the architect and his director

and construction foreman on the site.

Thus, rectangular schematism, identifiable with esoteric sacred numbers, was well-tailored in some respects to the practical needs of a

builder whose responsibilities, far removed from finely woven webs of theology, were characterized by mundane objectives, intolerant of

hocus-pocus.

E. B.

71.Za AACHEN, PALACE CHAPEL, BUILT BETWEEN 796 and 804

PLAN AND ELEVATIONS BY LEO HUGOT

GRID SUPERIMPOSED BY AUTHORS

The interesting and developmentally crucial significance of Leo Hugot's discovery of modular principles governing the organization of the Palace

Chapel at Aachen is its demonstration, by implication, that even a centrally planned Carolingian building cannot escape the power of

transformation which, at the age of Charlemagne, converts the Early Christian basilica into a modular structure.

The design of the Palace Chapel at Aachen is based on that of the church of San Vitale at Ravenna, begun around 532 and finished in 546.

In both buildings the shape and composition of the primary spaces as well as the formation of the basic morphological features are essentially the

same. In each case a tall octagonal center space with fenestrated and dome-surmounted drum is encircled by a peripheral envelope of outer

spaces, which, although internally divided into two stories (ambulatory and gallery) are, in their combined height, lower than the center space.

In each case the drum with its dome rests on eight huge arches, rising from piers erected in the eight angles of the octagon (cf. fig. 162.B).

These are the basic compositional and structural features. Yet in style and spatial concept the two buildings differ distinctly. In San Vitale the

shell separating the octagon from its spatial perimeter is made up of semicircular niches that billow out into the body of ambulatory and gallery.

Despite their intensive perforation (three arched openings on each level) these curved niches, together with the piers to which they are attached,

are aesthetically perceived as a continuous sheet of masonry stretched around the center space. The movement is encircling, not divisive, and the

enveloped space, being uninvaded by any of the enveloping features, retains its full corporeal solidity and homogeneity. It is sculpture springing

from a concept of spatial mass akin in spirit to the monolithic self-containment of the component spaces of the Early Christian basilica (Cf.

figs. 174 and 177.A-C).

The stylistic and conceptual archetype and prototype of this manner of molding space is the Roman Pantheon, a body of incomparable globular

perfection and beauty contained in a masonry shell of simple cylindrical shape whose surfaces pass in unbroken planar continuity into those of

the semicircular dome by which it is surmounted, with no intrusion at any point. The camera—one-eyed and stationary—is incapable of

capturing this quality of style, but Giovanni Piranesi, with his uncanny sensitivity for such matters, has portrayed it with great perspicuity in a

series of masterful engravings.

The design of the Palace Chapel at Aachen by contrast is based upon the concept of spatial divisibility. This quality is strikingly reflected in the

manner in which the eight component surfaces of the octagon meet and connect with one another. Instead of billowing niches swinging inward and

outward, yet never losing their encircling hold, the Chapel's straight surfaces, separated by sharp lines, rise in undisrupted ascent from the

ground to the apex of the vault by which it is covered. The dome over the octagon of San Vitale is circular (or nearly so) and therefore

detaches itself distinctly from the octagonal shape of the body of space lying beneath it, the transition from octagonal drum to circle of the dome

being achieved by means of squinches. It rests or hovers like a protective lid over the space it covers. The dome over the octagon of the Palace

Chapel, by contrast—a cloister vault, not a hemicycle!—is segmented into eight separate parts, like the eight sides of the octagonal shell that

supports it. The emphasis thus is shifted from connecting surfaces to separating lines. In Aachen, for this reason, the center space conveys the

feeling of being "sliced" or "sliceable" rather than "whole" and "rounded." It could aesthetically be defined as an aggregate of triangular

prisms, meeting with their sharp inner edges in the center axis of the building. This is divisive Carolingian modularity: the conceptual equivalent

of the modular square division of the Carolingian basilica (figs. 166-173); medieval divisionalism versus Classical corporeality.

The differences are discernible with even more striking sharpness in the structural articulation of the outer spaces. In San Vitale, ambulatory

and gallery were covered by timber roofs formed by continuous sequences of beams or trusses all lying on the same level, and therefore visually

perceived as flat and continuous annular planes (the present vaults are medieval; see Krautheimer, 1965, 170). In the Palace Chapel at Aachen

the same spaces are covered, on ground floor level by groin vaults of alternating square and triangular shape; and on gallery level, by rampant

barrel vaults alternating with sharply defined triangular spaces. This is cellular medieval organization of space, springing from the same

conceptual sources that in the longitudinal layout of the basilica lead to the arch-framed bay division of the Romanesque and the Gothic

(fig. 177); and for more visual demonstration, Horn and Born, Viator, 1975, figs. 38, 39.A-B.

Centrally planned buildings do not lend themselves with the same ease to modular division and, for that reason, are not part of the mainstream

of medieval development. One hundred and fifty years after the construction of the Palace Chapel, a sophisticated Florentine architect created in the

Baptistery of that city, a synthesis between classical and medieval, disclosing that even south of the Alps materials inherited from antiquity are

reshaped in a similar manner (cf. Horn, 1938, 99-155; reprinted 1973).

71.Zc FRONT ELEVATION

71.Zb SIDE ELEVATION

For the Plan of St. Gall, see Horn, 1965, 402-10 ("Das Modell eines

Karolingischen Idealkloster") and idem, 1965, 391-400 ("La Maquette

d'après le plan de St. Gall"). For the Palace grounds at Aachen, see

Hugot, ibid., 395-400 ("Die Pfalz Karls der Grossen in Aachen") and

385-390 ("Le palais de Charlemagne à Aix-la-Chapelle") as well as the

more detailed and more comprehensive analysis in Hugot, 1966, 534-72.

We acknowledge with profound gratitude Dr. Hugot's generosity in

allowing us to make use of his original drawings in the preparation of

the red overlays reproduced in figures 41.Y, 71.Y and 71.Za, b, c.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||