Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. | CHAPTER XXXI.

THE LAST BATTLE FOR THE REPUBLIC. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XXXI.

THE LAST BATTLE FOR THE REPUBLIC. Unwritten history | ||

31. CHAPTER XXXI.

THE LAST BATTLE FOR THE REPUBLIC.

TENDERLY at last I laid her down, and

moved about. Glad of something to do, I

gathered fallen branches, decayed wood, and

dry, dead reeds, and built a ready pyre.

I struck flints together, made a fire, and when the

surf of light again broke in across the eastern wall, I

lifted her up, laid her tenderly on the pile, composed

her face and laid her little hands across her breast.

I lighted the grass and tules. The fire took hold

and leaped and laughed, and crackled, and reached,

as if to touch the solemn boughs that bent and waved

from the cliffs above, as bending and looking into a

grave. I gathered white stones and laid a circle

around the embers. How rank and tall the grass is

growing above her ashes now! The stones have

settled and settled till almost sunk in the earth, but

this girl is not forgotten. This is the monument I

raise above her ashes and her faithful life. I have

written this that she shall be remembered, and properly

this narrative should here have an end.

The “Tale of the Tall Alcalde,” which men assert

on their own authority to be a true story of my life

here and her death, was written for her. I could not

then make it literally true, because the events were

too new in my mind. It had been like opening

wounds not yet half healed. I was then a judge in

the northern part of Oregon. I had, with one law

book and two six-shooters, administered justice successfully

for four years, and was then an aspirant for

a seat on the Supreme Bench of the State. Men who

had some vague knowledge of my life with the Indians

were seeking to get att the secrets of it and

accomplish my destruction. I wrote that poem, and

took upon myself all the contumely, real or fancied,

that could follow such an admission.

At sunrise I began to make my way slowly up the

river, towards the Indian camp, which I knew was

not more than a day's journey away. I ate berries

and roots as I could find them in my way, and at

night I entered the village and sat down by the door

of a lodge.

An old woman brought me water, but she could

not restrain her eagerness to know of my companions,

and at once broke the accustomed silence.

“Uti Paquita? Uti Olale?”

I pointed my thumbs to the earth.

She threw up her arms and turned away. The

camp was a camp of mourning, for nothing but defeat

they would mourn for Paquita and the brave young

warrior, and they went up to the hill-top among the

pines and filled the woods with lamentations.

Let us hasten to the conclusion of these unhappy

days. I rested a little while, then took part in a

skirmish, captured a few cavalry horses, and two

prisoners, whose lives I managed to save at the risk

of my own, for the Indians were now made desperate.

The Indians were now doing what little fighting was

done, entirely with arrows.

The Modoc Indians had exhausted all their arrows

and were returning home. A general despondency

was upon the Indians. No supplies whatever for the

approaching winter had been secured. The Indians

had been kept back from the fisheries on the rivers

and the hunting grounds in the valleys. The Indian

men had been losing time in war and the Indian

women in making arrows and nursing the wounded.

Even in the plentiful season of early autumn a famine

was looking them in the face.

No gentleness marked our actions now; I did not

restrain my Indians in any ruthless thing they undertook

short of taking the lives of prisoners.

I made a hurried ride through the Modoc plains

around Tula lake and saw there but little hope of

continuing a successful struggle as it was then being

conducted. Lieutenant Crook, now the General

military post on the head-lakes of Pit river. This

was in the heart of the Indian country, and almost

on the spot where the three corners of the lands of

the three tribes met, and he could from this point

reach the principal valleys and the great eastern

plains of the Indians with but little trouble.

A new and most desperate undertaking now entered

my mind. It was impossible to dislodge the military

from the Indian country as things then stood. I

resolved to “carry the war into Africa.”

I laid my plan before the Modocs, and they, poor

devils, made desperate with the long and wasting

struggle, were mad with delight.

It was resolved to gather the Indian forces together,

send the women and children into the caves to hide

and subsist as best they could, leave our own homes,

and then boldly descend upon the white settlements.

This we were certain would draw the enemy, for a

time at least, from our country.

I never witnessed such enthusiasm. These battle-scarred,

worn-out, ragged, half-starved Indians arose

under the thought of the enterprise as if touched by

inspiration.

I was to go down to Yreka, note the approaches

to the town, the probable strength of the place, the

proper time to attack, while they gathered their

forces together for the campaign and disposed of the

women and children.

The attack was to be made on the city itself.

There we were to strike the first blow. The plan

was to move the whole available Indian force to the

edge of the settlement and there leave the main

body. Then I was to take the flower of the force,

mounted on the swiftest horses, and, descending upon

the town suddenly, attack, sack, and burn it to the

ground.

We had had many a lesson in this mode of warfare

from the whites and knew perfectly well how the

work was to be done.

I mounted a strong, fleet horse and set out. On

reaching the mountain's rim overlooking the valley I

was struck by the peaceful scene below me. All

the fertile plain was dotted yellow, and brown, and

green from fields of grain. It looked like some

great map. Peace and plenty all the way across the

valley to the city lying on the other side, and thirty

miles ahead.

At dusk I came to a quiet farm-house and asked

for hospitality.

The old settler came bustling out bare-headed and

in his shirt-sleeves, as if he was coming to welcome

a son.

He took care of my horse, hurried me into the

house, hurried his good wife about the kitchen, and

I soon was seated at the table of a Christian eating a

Christian meal.

It was the first for a long, long time; I fell to

thinking as of old, and held down my head.

After supper the old man sat and talked of his

cattle and his crops and the two children climbed

about my knees.

No sign of war here. Not a hundred miles away

a people all summer had been battling for their firesides,

for existence, and yet it had been hardly felt

in the settlements. Such is the effect of the quiet,

steady, eternal warfare on the border. It is never

felt, never hardly heard of, till the Indians become

the aggressors which is seldom indeed.

The old lady came at last and sat down with her

knitting and a ball of yarn in her lap. She talked

of the price of butter and eggs, and said they should

soon be well-to-do and prosperous in their new

home.

I retired early, and rising with the dawn, left a

gold coin on the table, and rode rapidly toward the

city.

I was not satisfied with my desperate and bloody

undertaking. As I passed little farm-houses with

vines and blossoms and children about the doors, I

began to wonder how many kind and honest people

were to be ruined in my descent upon the settlements.

The city I found assailable from every side. There

was not a soldier within ten miles. Fifty men could

a hundred places, and then ride out unhindered.

It seems a little strange that I met kindness and

civility now when I did not want it. Of course I

was utterly unknown, and having taken care from

the first to dress in the plainest and commonest dress

of the time, there was not the least suspicion of my

name or mission.

As I rode back, the farmers were gathering in their

grain. On the low marshy plains of Shasta river

they were mowing and making hay. I heard the

mowers whetting their scythes and the clear ringing

melody came to me full of memories and stories of

my childhood.

I passed close to some of these broad-shouldered

merry men, as they sat on the grass at lunch, and

they called to me kindly to stop and rest and share

their meal. It was like merry hay-making of the

Old World. All peace, merriment and prosperity

here; out yonder, burning camps, starving children,

and mourning mothers; and only a hundred miles

away.

I did not again enter a house or partake of hospitality.

I slept on the wild grass that night, and in

another day rode into the camp where the Indians

had gathered in such force as they could to await my

action.

A council was called, and I told them all. I told

was feasible, and yet I could not lead them where

women and children and old men and honest labourers

would be ruined, and perish alike with the

arrogant and cruel destroyers. An old man answered

me; his women, his children, his old father, his

lodges, his horses had all been swept away; it was

now time to be revenged and then to die.

Never have I been placed in so critical a position,

never have I been so crucified between two plans of

life. But I had said when I climbed the mountain

and looked back on the green and yellow fields and

peaceful farm-houses below, that I would not lead

my allies there, come what might, and I doggedly

kept my promise through all the stormy council of

that long and unhappy night.

Time has shown that I was wrong; I should have

taken that city and held on, and kept up an aggressive

warfare till the Government came to terms, and

recognized the rights of this people.

I rode south with my warriors, and we gathered in

diminished force on a plateau not far from Pit River,

and prepared to make another fight.

If there is a race of men that has the gift of

prophecy or prescience I think it is the Indian. It

may be a keen instinct sharpened by meditation that

makes them foretell many things with such precision;

but I have seen some things that looked much like

the fulfilment of prophecies.

They believe in the gift of prophecy thoroughly

and are never without their seers. Besides the warriors

are constantly foretelling their own fate. A distinguished

warrior rarely goes into battle without

telling what he will do, whom he will encounter, who

will be killed, and how the battle will be determined.

They often foretell their own deaths with a singular

accuracy. They believe in signs of all kinds: signs

in the heavens, signs in the woods, on the waters, anywhere;

and a chief will sometimes suddenly, in the

midst of battle, call off his warriors even when about

to reap a victory, should a sign inauspicious appear.

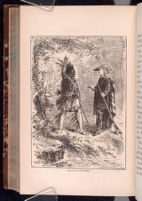

Klamat, shadowy, mysterious, dark-browed little

Klamat, now a tall and sinewy warrior, was strangely

thoughtful all this time. He went about his duties

as in a dream, but he left no duty unperformed. He

prepared his arms and all things for the approaching

battle with the utmost care. He bared his limbs

and breast and painted them red, and bound up his

hair in a flowing tuft with eagle feathers pointing

up from the defiant scalp-lock.

At last he painted his face in mourning. That

means a great deal. When a warrior paints his face

black it means victory or death. When a warrior

paints his face black before going into battle he does

not survive a defeat. It is rarely done, but an

Indian is greatly honoured who goes to this extreme,

and when he goes out to battle the women sit on

KLAMAT'S PROPHECY

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. To the left, a Black man stands with his right hand raised, pointing his finger towards the heavens. He holds a gun in his left hand and there is a dagger in his belt. He is looking at a white man. The white man is holding a gun which has its butt on the ground, and has his right hand slightly raised. ]

with his name in a kind of chorus, calling their deity

to witness his valour to defend him in battle, and

bring him back victorious.

I was standing down by the river alone, waiting

and looking in the water, when he came and laid his

hand upon my shoulder. He had his rifle in his

other hand and his knife, tomahawk, and pistol in his

belt. He looked wild and fierce. He scarcely spoke

above a whisper.

“I will not come back,” he began, “I have seen the

signs, and I shall not come back. It is all right, I

am going to die like a chief. To-morrow I will be

with my people on the other side of darkness.

They will meet me on my way, for I have had their

revenge.”

He looked at me sharp and sudden, and his black

eyes shot fire. He lifted his hand high above his

head and twirled it around as if shaping a beaver

hat. His eyes danced with a fierce delight as he

hissed between his teeth,

“The Judge! Spades!”

He struck out savagely, as if striking with a knife;

as if these men stood before him, and then laid his

hand upon his own breast.

Great Heavens! I said to myself, as he shouldered

his rifle and joined his comrades, and it was this boy

that killed them. The Doctor and the Prince had

with the secret. They had borne the peril and reproach

that they might save these two and bring

them back beyond the reach of the white man. I

never till that moment knew how great and noble

were the two men whose lives mine had touched,

spoken to, and parted from as ships that meet and

part upon the seas.

We had to fight a mixed body of soldiers and

settlers, and a short, but for the Indians bloody,

battle took place.

The chief of the Pit River Indians fell, and many

of his best warriors around him. Early in the fight

I received an ugly cut on the forehead, which bled

profusely and so blinded me that I could do nothing

further for my unhappy allies. It was a hopeless

case. While the fight waxed hot I stole off up a

canon with a number of the Shasta Indians and

escaped. I came upon an old wounded warrior

leaning on his bow by the trail. The old man said

“Klamat!” bowed his head and pointed to the

ground.

The prophecy had been fulfilled.

Do not imagine these were great battles. Other

events had the ears of the world then, and they

were probably hardly heard of beyond the lines

of the State. Half armed, and wholly untrained, the

Indians could not or did not make a single respectable

their side.

Had they been able to make one or two bold

advances against the whites, then negotiations would

have been opened, terms offered, opinions exchanged,

rights and wrongs discussed, and the Indians would

at least have had a hearing. But so long as the

troops had it their own way, the only terms were the

Reservation, or annihilation.

The few remaining Modoc warriors now returned

to their sage-brush plains and tule lakes to the east;

the Shastas withdrew to the head-waters of the

McCloud, thus abandoning lands that it would take

you days of journey to encompass; and the Pit

River Indians, now almost starving, with an approaching

winter to confront, sent in their remaining women

and children in sign of submission. They were

sadly reduced in numbers, and perhaps less than a

thousand were taken to the Reservation. To-day

the tribe is nearly extinct.

And why did the Government insist to the bitter

end that the Indians should leave this the richest

and finest valley of northern California? Because

the white settlers wanted it. Voters wanted it, and

no aspirant for office dared say a word for the Indian.

So it goes.

The last fight was a sort of Waterloo. There was

now no hope. My plans for the little Republic were

upon the Indians and destruction upon myself by

remaining. I resolved to go.

At last a thought like this began to take shape. I

will descend into the active world. I will go down

from my snowy island into the strong sea of people,

and try my fortunes for only a few short years.

With this mountain at my back, this forest to retreat

to if I am worsted, I can feel strong and brave; and

if by chance I win the fight, I will here return and

rest.

My presence there, instead of being a protection, was

only a peril now to the Indians. I told Warrottetot,

the old warrior, frankly that I wished to go, that it

was best I should, for the white men could not

understand why I was there, except it was to incite

them to battle or plunder.

I sat down with him by the river, and with a stick

marked out the world in the sand, showed him how

narrow were his possessions now, and told him where

all his wars must end. He gave me permission to go,

and said nothing more. He seemed bewildered.

The old chief, the day before my departure, rode

down with me from the high mountains to the beautiful

Now-aw-aw valley, where I had built a cabin

years before. We stopped on a hill overlooking the

valley and dismounted; he took fragments of lava

and built a little monument. He pointed out high

as much land as you could journey around in a day's

travel.

“This is yours. All this valley is yours; I give

it to you with my own hand.” He went down the

hill a little way, and taking up some of the earth

brought it to me and sprinkled it upon and before

my feet.

“It is all yours,” he said, “you have done all you

could do, and deserve it; besides, I have no one to

leave it to now but you.”

“You will go on your way, will win a place among

your own people, and when you return you will have

lands, a home and hunting-grounds. These you will

find here when you return, but you will not find me,

nor one of my children, nor one of my tribe.”

The poor old Indian, battle-worn, wounded and

broken in spirit, was all heart, all tenderness and

truth and devotion. He could not understand why

that land should not be wholly mine. He had not

the shadow of a doubt that this gift of his made the

little valley as surely and wholly mine as if a thousand

deeds had testified to the inheritance. He could

not understand why he was not the lord and owner

of the land which had been handed down to him

through a thousand generations, that had been fought

for and defended from a time as old, perhaps, as the

history of the invader.

Under the madronos my horse stood saddled for a

long, hard ride. Good-byes were said, I led my

steed a little way, and an Indian woman walked at

my side.

Some things shall be sacred. Recital is sometimes

profanity.

It was a sudden impulse that made me set my

horse back on his haunches as he bounded away, unwind

my red silk sash, wave a farewell with it, toss

it to her, and bid her keep it till my return. In less

than forty days, I rested beneath the palms of Nicaragua.

| CHAPTER XXXI.

THE LAST BATTLE FOR THE REPUBLIC. Unwritten history | ||