Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. | CHAPTER XXI.

MY FIRST BATTLE. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XXI.

MY FIRST BATTLE. Unwritten history | ||

21. CHAPTER XXI.

MY FIRST BATTLE.

ABOUT this time, tiring somewhat of the

monotonous life of the Indian camp, and

wishing to see the face of a white man, I

descended to the settlements on the Sacramento River,

and fell in with Mountain Joe, an old mountaineer

who had been with Fremont. He was a German by

birth and education, and remarkable as it may seem,

was certainly a very learned man. I have heard him

repeat, or at least pretend to repeat, Homer in the

Greek and Virgil in the Latin, by the hour, though

he professed to despise the translations, and would

not give me a line of the English version. Possibly,

his Greek was not Greek, but I think it was, for in

other things in which I could not be utterly deceived

I found him wonderfully well-informed.

We together located and took possession of the

ranch now known as the Soda Springs, and to-day the

most famous summer resort in northern California.

We employed men, built a house, ploughed, planted,

a few weeks. Sometimes I would ride up into the

mountains towards Mount Shasta, as if hunting for

game, and spend a few days with my tawny friends.

Soon the rush of people subsided, and but few

white men were found in the country. All up and

down the streams their temporary shanties were left

without a foot to press the rank grass and abundant

weeds.

One day when our tame Indians, whom we had

employed on the ranch, were out fishing, and Mountain

Joe and I had taken our rifles and gone up the

Narrow Valley to look after the horses, a band of

hostile Indians living in and about the Devil's Castle,

some ten miles away on the opposite side of the

Sacramento, came in and plundered our camp of

all the stores and portable articles they could lay

hands on.

This castle is the most picturesque object in all the

magnificent scenery of northern California. It sits

on a high mountain, and is formed of grey granite

blocks and spires, lifting singly and in groups thousands

of feet from the summit of the mountain. Most

of these are inaccessible. Here the Indians locate

the abode of the devil. Hence its name.

I gathered up some half-tame Indians that could

be relied on, while Mountain Joe went down the

river ten or twenty miles to the little mining camps,

no connection with these Indians, and was therefore

plundered and treated as they would have treated any

other settler. To have borne with the outrage would

have been to fall into disgrace with the others. They

would have thought I dared not resent it.

The small command moved up Castle Creek under

the guide of friendly Indians. Each man carried his

arms, blankets, and three days' rations. All were

on foot, as the Castle cannot be approached by horsemen.

We reached Castle Lake, a sweet, peaceful

place, overhung by mountain cypress and sweeping

cedars. This is a spot the Indians will not visit, for

fear of the evil spirits which they are certain inhabit

the place. They sat down in the wood overlooking

the lake, while we descended, drank of the cool, deep

water, and refreshed ourselves for the combat, since

the spies had just returned and reported the hostile

camp only an hour distant. This was on the 26th

day of June, 1855. The enemy was not dreaming of

our approach, and we were in position, almost surrounding

the camp, before we were discovered.

Mountain Joe had distributed us behind the rocks

and trees in range of and overlooking the camp.

The ground was all densely timbered, and covered

with a thick growth of black stiff chaparral, save

one spot of a few acres, by the side of which the

Indians were camped, at the foot of a little hill.

This was my first war-path. I was about to take

part in my first real battle. I had been placed by

Mountain Joe behind a large pine, and alone. He

spoke kindly as he left me, and bade me take care of

myself.

I put some bullets in my mouth, primed my pistols,

and made all preparation to do my part. It seemed

like an age before the fight began. I could hear my

heart beat like a little drum.

The Indians certainly had not the least suspicion

of danger. They were, it seemed, as much off their

guard as possible. They evidently thought their

camp, if not impregnable, beyond our reach and discovery.

They owed the latter to their own race.

At last we were discerned, as some of the most

daring and experienced were stealing closer and

closer to the camp, and they sprang to their arms

with whoops and yells that lifted my hat almost from

my head.

The yells were answered. Rifles cracked around

the camp, and arrows came back in showers.

“Close up!” shouted Mountain Joe, and we left

cover and advanced. I think I must have swallowed

the bullets I put in my mouth, for I loaded from my

pouch as usual, and thought of them no more as we

moved down upon the yelling Indians.

A little group of us gathered behind some rocks.

Then a man came creeping to us through the brush

pressed and that we must move on. Then another

came to say that Mountain Joe had been struck

across the face by an arrow, and his eyes were so

injured that he could not direct the fight.

“Then come on!” I cried; “let us push through

here to the camp and drive them into the open

ground.” I took the lead, the men followed, and

without knowing it, I became a leader of my fellows.

We had wound our blankets about our breasts and

bodies so as to guard against arrows, but our heads

were unprotected.

Suddenly the arrows came, whiz, whistle, thud,

right in our faces.

I fell senseless. After a while I felt men pulling

by my shoulders. I could hear and understand but

could not see or rise. It seemed to me they were

trying to twist my neck from my body. Yet I

felt no great pain, only a numbness and utter helplessness.

“Help me pull it out,” said one. They pulled.

“No, you must cut off the point, and then pull it

back.”

Then they cut and pulled, and the blood spurted

out and rattled on the leaves.

“Poor boy, he's done for.”

I could now see, but was still helpless. Half-a-dozen

men stood around leaning on their rifles,

MY FIRST BATTLE.

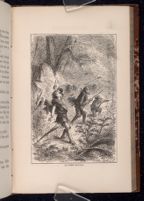

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. This is a battle-scene. A white man is raising a dagger in his hand, and his hat has blown off. He is being shot by an arrow in the throat and he has just dropped his gun. Two other white men are also in the battle. One is aiming a gun off to the rights. The other has his gun in his hands and is looking off tot the right. Three are three Indians in the background which are aiming arrows. There are also arrows flying towards the men. They are in the woods.]

By the side of me, with his head in a man's lap, lay

a young man, James Lane, with an arrow-shot near

the eye. I believe he died of his wound.

The fight was over. An arrow had struck me in

the left side of the face, struck the jaw-bone, and

then glanced around and came out at the back of the

neck. The wound certainly looked as if it must be

mortal, but the jugular vein was not touched and there

was hope. I was dizzy and sometimes senseless. This

perhaps was because the wound was so near the brain.

I constantly thought I was on the mountain slope

overlooking home, and kept telling the men to go

and bring my mother. We had no surgeon, and the

men tied up our wounds as best they could in

tobacco saturated in saliva.

That night the Indian camp was plundered and

burnt. The next morning, as the provisions were out,

preparations were made to descend the mountain. I

here must not forget the kind but half-savage attention

of these rough men. They could do but little,

it is true, but they were untiring in attention and

sympathy. They held my head in their laps, and

talked low and tenderly of early health and my return

home. I saw one man crying, the tears dropping

down into his long grizzly beard; then I thought I

should surely die.

In the morning one kind but mistaken old fellow

before my eyes in his left hand, while he tapped it

gently with his bowie knife. The blood was oozing

through the seams of the bag and trickling at his feet.

“Them's scalps.”

I grew sick at the sight.

The wounded were carried on the backs of squaws

that had been taken in the fight. A very old and

wrinkled woman carried me on her back by setting

me in a large buckskin, with one leg on each side of

her body, and then supporting the weight by a broad

leather strap passed across her brow. This was not

uncomfortable, all things considered. In fact, it was

by far the best thing that could be done.

The first half day the old woman was “sulky,” as

the men called it; possibly the wrinkled old creature

could feel, and was thinking of her dead.

In the afternoon I began to rally, and spoke to her

in her own tongue. Then she talked and talked,

and mourned, and would not be still. “You,” she

moaned, “have killed all my boys, and burnt up my

home.”

I ventured to protest that they had first robbed us.

“No,” she said, “you first robbed us. You drove

us from the river. We could not fish, we could not

hunt. We were hungry and took your provisions to

eat. My boys did not kill you. They could have

killed you a hundred times, but they only took

on the river.”

We reached the Sacramento in safety, and pitched

camp on the bank of the river under some sweeping

cedars about a mile below the site of the present

hotel on the Lower Soda Spring ranch. Here I lay a

long time, till able to travel. Those beautiful trees

were still standing when I returned there in 1872.

It was necessary to go to San Francisco to recover

my health; but I tired of the city soon, and longed

for the mountains and my Indian companions.

In the spring I returned, found Mountain Joe

ploughing and planting at Soda Springs, and after

resting and making arrangements for the further improvement

of the ranch, pushed back over the mountains

to my Indians. All were there, Paquita, Klamat,

the chief, and his daughter, who, although she

was much to me I shall barely mention in these

pages. This is a book not of the Indian woman's

love, but of the white man's hate. They had learned

all about my battle, and I think forgave me whatever

blood was on my hands for the part I had borne

in the fight, for an Indian is a hero-worshipper of the

very worst kind.

| CHAPTER XXI.

MY FIRST BATTLE. Unwritten history | ||