Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. | CHAPTER XVIII.

GOOD-BYE. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XVIII.

GOOD-BYE. Unwritten history | ||

18. CHAPTER XVIII.

GOOD-BYE.

THESE Indians, and all Indians for that

matter, have some strange customs, at which

we laugh, or talk of in a mild, missionary,

patronizing sort of a way.

Did it ever occur to an American sovereign, as he

lifted up his voice in the public places, and thanked

God that he is not as Indians are, that they may

possibly laugh at some of his customs too? I think

it never did.

When an Indian gets sick his friends have a dance.

When a white man begins to lose his hair he rushes

off to a barber, and has what he has left cut off to

the scalp. Nature, always obliging, comes to his

assistance then; and he never has to have any great

portion of it cut again, but is permitted to make the

rest of the journey with his head as bright and

naked as a globe.

Very odd to have a dance when you get ill; but

not half so odd as it is to cut off your hair to save

women also, who until recently wore their hair

nearly natural, never are bald. Yet I reckon men

have gone on cutting their hair for baldness, the very

thing that brings it on, for thousands of years past,

and, I suppose, will still go on doing so for thousands

of years to come.

We received some visits now from the chief of the

Shastas. He was not a tall man, as one would

suppose who had seen his warriors, but a giant in

strength. You would have said, surely this man is

part grizzly bear. As I have said before, he was

bearded like a prophet.

I now began to spend days and even weeks in the

Indian village over towards the south in a canon,

took part in the sports of the young men, listened to

the teachings and tales of the old, and was not unhappy.

The Prince was losing his old cheerfulness as

the summer advanced, and once or twice he half

hinted of taking a long journey away to the world

below.

At such times I would so wish to ask him where

was his home, and why he had left it, but could not

summon courage. As for myself, let it be here

understood, once for all, that when a man once casts

his lot in with the Indians he need return to his

friends no more, unless he has grown so strong of

with them disgraced for ever. I had crossed the

Rubicon.

It was the time of the Autumn Feasts, when the

Indians meet together on a high oak plain, a sort of

hem of the mountain, overlooking the far valley of

the Sacramento, to celebrate in dance and song

their battles of the summer and recount the virtues

of their dead. On this spot, among the oaks, their

fathers had met for many and many a generation.

Here all were expected to come in rich and gay

attire, and to give themselves up to feasting and

the dance, and show no care in their faces, no

matter how hard fortune had been upon them.

Indian summer, this. A mellowness and balm in

all the atmosphere; a haze hanging over all things,

and all things still and weary like, like a summer

sunset.

The manzineta-berries were yellow as gold, the

rich anther was here, the maple and the dogwood that

fringed the edge of the plain were red as scarlet, and

set against the wall of firs in their dark, eternal green.

The scene of the feast was a day's ride from the

cabin, and the Prince and I were expected to attend.

Paquita would of course be there, and who shall

say we had not both looked forward to this day with

eagerness and delight?

Gold, in any quantity, except in romance, is the

you in your wanderings in the mountains you can

imagine.

We had saved only a trifle of dust compared to the

amount report credited us with. This we put in

four little buckskin bags, each taking two and placing

them one in the left and one in the right pocket of

his catenas. This held them to their places in hard

rides; besides it was a sort of laying in of stores for

some storm that might blow in upon us at any moment.

Even if the lessons of the squirrels and the Indian

women, all the autumn days laying up their stores

for winter, had gone for nought, the lesson of the

Humbug miners was not forgotten. And yet I had

no idea that any grave danger could overtake us

there, and I am certain I had no desire to leave the

peaceful old forests and the calm delight of the

mountain camp.

Of course I was very silly, as most young people

are; but it seemed to me the world below was but

a small affair, and all the people in it of but little

consequence, so long as Paquita and the Prince

were remaining in the mountains.

Had they gone down into the world, then the

mountains had been rugged and cold enough, no

doubt, and the world below much like home; but

while they remained I had no thought of going

away.

The mine did not promise much after all. We

began to have a strong suspicion that we had only

chanced upon a pouch in the rock—a little “chimney”

that nurses a few thousand dollars' worth of dust

about the flue, and nothing more—with the quartz

rock back of this, as barren and hard as flint. A

common thing is this, and the most disappointing of all

things. Years ago, before the miners began to learn

this, many a fortune was squandered in erecting

mills on ledges that never offered any further reward

than the one little pocket.

We went to the feast—rode through the forest

in a sort of dream. How lovely! The deer were

going in long bands down their worn paths to the

plains below, away from the approaching winter.

The black bears were fat and indolent, and fairly

shone in their rich oily coats, as they crossed the

trail before us.

Hundreds were at the feast, and we were more

than welcome. The Chief came first, his warriors

by his side, to give us the pipe of peace and welcome,

and then a great circle gathered around the fire, seated

on their robes and the leaves; and as the pipe went

round, the brown girls danced gay and beautiful,

half-nude, in their rich black hair, and flowing robes.

But Paquita was shy. She would not dance,

for somehow she seemed to consider that this

was a kind of savage entertainment, and out of place

to deprive her of the pleasures of the wild and free.

There had grown a cast of care upon her lovely

face of late. She was in secret of all the Indians'

plans. At least she was a true Indian—true to the

rights of her race, and fully awake to a sense of their

wrongs.

She was surely lovelier now than ever before; tall,

and lithe, and graceful as a mountain lily swayed by

the breath of morning. On her face, through the

tint of brown, lay the blush and flush of maidenhood,

the indescribable sacred something that makes a

maiden holy to every man of a manly and chivalrous

nature; that makes a man utterly unselfish, and perfectly

content to love and be silent, to worship at a

distance, as turning to the holy shrine of Mecca, to

be still and bide his time; caring not to possess

in the low coarse way that characterizes your

common love of to-day, but choosing rather to go

to battle for her,—bearing her in his heart through

many lands, through storms and death, with only

a word of hope, a smile, a wave of the hand from a

wall, a kiss blown far, as he mounts his steed below

and plunges into the night. That is a love to live

for. I say the knights of Spain, bloody as they

were, were a noble and a splendid type of men in

their way.

The Prince was of this manner of men. He was

of Spain, a hero born out of time, and blown out of

place, in the mines and mountains of the North.

Once he had taken Paquita in his arms, had folded

a robe around her as if she had been a babe. She

was all—everything to him. He renounced all this.

Now he did not even touch her hand.

The old earnestness and perplexity had come upon

the Prince again on our coming to the feast. Once,

when the dance and song ran swift and loud and

all was merriment, I saw him standing out from

the circle of warriors, of young maidens and men,

with folded arms, looking out on the land below.

I had too much respect, nay reverence, for this man

to disturb him. I leaned against a tree and looked

as he looked. Once his eyes left the dance before

him, and stole timidly toward the place where

Paquita sat with her brother watching the dance.

What a devotion in his face. I could not understand

him. Now he turned to the valley again, tapped

the ground with his foot in the old, restless way,

but his eyes soon wandered back to Paquita. At

last my gaze met his. He blushed deeply, held down

his head and walked away in silence.

The next day was the time set apart for feats of

horsemanship. The band was driven in, all common

property, and the men selected their horses. The

Prince drew out with his lasso a stout black steed,

THE FAREWELL.

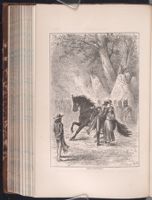

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A white man stands next to a horse and he has his arm wrapped around a young female Indian. He is kissing her. Another white man watches the couple. Many Indians, clustered near teepees in the background, are also watching on. ]

either side, or stood erect like a crest; a wiry, savage,

untrained horse that struck out with his feet, like an

elk at bay. He saddled him, and led him out all

ready now, where the other horses stood in line, then

came to me, walked a little way to one side, put out

one hand and with the other drew me close to him,

held down his head to my uplifted face, and said,

“Good-bye.”

I sprang up and seized hold of him, but he went

on calmly—

“I must go away. You are happy here; you will

remain, but I must go. After many years I will

return. You will meet me here on this spot, years

and years from to-day. Yes, it will be many years;

a long time. But it is short enough, and long enough.

I will forget her—it—I will forget by that time, you

see, and then there is all the whole world before me

to wander in.”

He made the sign of departure. The chief came

forward, Paquita came and stood at his side. He

reached his hands, took her in his arms, pressed her

to his breast an instant, kissed her pure brow once,

with her great black eyes lifted to his, but said no

word.

The Indians were mute with wonder and sorrow.

When you give the sign of going, there is no one to

say nay here. No one importunes you to stay; no

such folly. You know that you are welcome to one

and all, and they know that if you wish to go, you

wish to go, and that is all there is of it. This is the

highest type of politeness; the perfect hospitality.

The Prince turned to his steed, drew his red silk

sash tighter about his waist, undid the lasso, wound

the lariat on his arm, and wove his hand in the flowing

mane as the black horse plunged and beat the

air with his feet. Then he set him back on his

haunches, sprang from the ground, and forward

plunged the steed with mane like a storm, down the

place of oaks, pitching towards the valley.

The trees seemed to open rank as he passed, and

then to close again; a hand was lifted, a kiss thrown

back across the shoulder, and he was gone—gone

down in the sea below us, and I never saw my Prince

again for many a year. Noble, generous, self-denying

Prince! The most splendid type of the chivalric and

the perfect man I had ever met.

All this was so sudden that I hardly felt the

weight of it at first, and for want of something to

do to fill the blank that followed, I mounted my

horse and took part in the sports with the gayest of

the gay.

Indians do not speak of anything that happens

suddenly. They think it over, all to themselves, for

days, unless it is a thing that requires some action

cautiously and casually. It is considered very vulgar

indeed to give any expression to surprise, and

nothing is more out of taste than to talk about a

thing that you have not first had good time to think

about.

During the day I noticed that my catenas were

heavier than usual, and unfastening the pockets, I

found that they contained all four of the bags of

gold.

Why had he left himself destitute? Why had

he gone down to battle with the world without a

shield?—gone to fight Goliath, as it were, without

so much as a little stone. I wanted to follow him

and make him take the money—all of it. I despised

it, it made me miserable. But I had learned to obey

him, to listen to him in all things. And was he not

a Prince?

“Ah!” said I to myself, at last, “he has gone

down to take possession of his throne. He will

cross the seas and see maidens fair indeed, nearly as

lovely in some respects as Paquita;” and this was

my consolation.

“Years and years,” I said to myself that night as I

looked in the fire, and the dance went on; “Years

and years!” I counted it upon my fingers, and said

—“I will be dead then.”

| CHAPTER XVIII.

GOOD-BYE. Unwritten history | ||