Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. | CHAPTER I.

SHADOWS OF SHASTA. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER I.

SHADOWS OF SHASTA. Unwritten history | ||

1. CHAPTER I.

SHADOWS OF SHASTA.

AS lone as God, and white as a winter moon,

Mount Shasta starts up sudden and solitary

from the heart of the great black forests of

Northern California.

You would hardly call Mount Shasta a part of the

Sierras; you would say rather that it is the great

white tower of some ancient and eternal wall, with

here and there the white walls overthrown.

It has no rival! There is not even a snow-crowned

subject in sight of its dominion. A shining pyramid

in mail of everlasting frosts and ice, the sailor sometimes,

in a day of singular clearness, catches glimpses

of it from the sea a hundred miles away to the west;

and it may be seen from the dome of the capital 340

miles distant. The immigrant coming from the east

beholds the snowy, solitary pillar from afar out on

silence as in answer to a sign.

Column upon column of storm-stained tamarack,

strong-tossing pines, and war-like looking firs have

rallied here. They stand with their backs against

this mountain, frowning down dark-browed, and confronting

the face of the Saxon. They defy the advance

of civilization into their ranks. What if these

dark and splendid columns, a hundred miles in depth,

should be the last to go down in America! What

if this should be the old guard gathered here, marshalled

around their emperor in plumes and armour,

that may die but not surrender.

Ascend this mountain, stand against the snow

above the upper belt of pines, and take a glance below.

Toward the sea nothing but the black and

unbroken forest. Mountains, it is true, dip and

divide and break the monotony as the waves break

up the sea; yet it is still the sea, still the unbroken

forest, black and magnificent. To the south the

landscape sinks and declines gradually, but still maintains

its column of dark-plumed grenadiers, till the

Sacramento Valley is reached, nearly a hundred miles

away. Silver rivers run here, the sweetest in the

world. They wind and wind among the rocks

and mossy roots, with California lilies, and the yew

with scarlet berries dipping in the water, and trout

idling in the eddies and cool places by the basketful.

rank till the Pit River valley is reached; and even

there it surrounds the valley, and locks it up tight

in its black embrace. To the north, it is true, Shasta

valley makes quite a dimple in the sable sea, and

men plough there, and Mexicans drive mules or herd

their mustang ponies on the open plain. But the

valley is limited, surrounded by the forest confined

and imprisoned.

Look intently down among the black and rolling

hills, forty miles away to the west, and here and there

you will see a haze of cloud or smoke hung up above

the trees; or, driven by the wind that is coming from

the sea, it may drag and creep along as if tangled in

the tops.

These are mining camps. Men are there, down in

these dreadful canons, out of sight of the sun, swallowed

up, buried in the impenetrable gloom of the

forest, toiling for gold. Each one of these camps is

a world in itself. History, romance, tragedy, poetry

in every one of them. They are connected together,

and reach the outer world only by a narrow little

pack trail, stretching through the timber, stringing

round the mountains, barely wide enough to admit

of footmen and little Mexican mules with their

apparajos, to pass in single file. We will descend

into one of these camps by-and-by. I dwelt there a

year, many and many a year ago. I shall picture

Giants were there, great men were there.

They were very strong, energetic and resolute, and

hence were neither gentle or sympathetic. They

were honourable, noble, brave and generous, and yet

they would have dragged a Trojan around the wall

by the heels and thought nothing of it. Coming

suddenly into the country with prejudices against

and apprehensions of the Indians, of whom they

knew nothing save through novels, they of course

were in no mood to study their nature. Besides,

they knew that they were in a way, trespassers if

not invaders, that the Government had never treated

for the land or offered any terms whatever to the

Indians, and like most men who feel that they

are somehow in the wrong, did not care to get

on terms with their antagonists. They would have

named the Indian a Trojan, and dragged him

around, not only by the heels but by the scalp, rather

than have taken time or trouble, as a rule, to get

in the right of the matter.

I say that the greatest, and the grandest body of

men that have ever been gathered together since the

seige of Troy, was once here on the Pacific. I grant

that they were rough enough sometimes. I admit

that they took a peculiar delight in periodical six-shooter

war dances, these wild-bearded, hairy-breasted

men, and that they did a great deal of promiscuous

such a manly sort of way!

There is another race in these forests. I lived

with them nearly five years. A great sin it was

thought then, indeed. You do not see the smoke of

their wigwams through the trees. They do not

smite the mountain rocks for gold, nor fell the pines,

nor roil up the waters and ruin them for the fishermen.

All this magnificent forest is their estate.

The Great Spirit made this mountain first of all, and

gave it to them, they say, and they have possessed it

ever since. They preserve the forest, keep out the

fires, for it is the park for their deer.

I shall endeavour to make this sketch of my life

with the Indians—a subject about which so much has

been written and so little is known—true in every

particular. In so far as I succeed in doing that I

think the work will be novel and original. No man

with a strict regard for truth should attempt to write

his autobiography with a view to publication during

his life; the temptations are too great.

A man standing on the gallows, without hope of

descending and mixing again with his fellow men,

might trust himself to utter “the truth, the whole

truth, and nothing but the truth,” as the law hath it;

and a Crusoe on his island, without sail in sight or

hope of sail, might be equally sincere, but I know of

few other conditions in which I could follow a man

This narrative, however, while the thread of it is

necessarily spun around a few years of my early life,

is not particularly of myself, but of a race of people

that has lived centuries of history and never yet had a

historian; that has suffered nearly four hundred years

of wrong, and never yet had an advocate.

I must write of myself, because I was among these

people of whom I write, though often in the background,

giving place to the inner and actual lives of

a silent and mysterious people, a race of prophets;

poets without the gift of expression—a race that has

been often, almost always, mistreated, and never

understood—a race that is moving noiselessly from

the face of the earth; dreamers that sometimes waken

from their mysteriousness and simplicity, and then,

blood, brutality, and all the ferocity that marks a man

of maddened passions, women without mercy and

without reason, brand them with the appropriate

name of savages.

But beyond this, I have a word to say for the

Indian. I saw him as he was, not as he is. In

one little spot of our land, I saw him as he was

centuries ago in every part of it perhaps, a Druid and

a dreamer—the mildest and the tamest of beings.

I saw him as no man can see him now. I saw him

as no man ever saw him who had the desire and

patience to observe, the sympathy to understand, and

those who would really like to understand him.

He is truly “the gentle savage;” the worst and the

best of men, the tamest and the fiercest of beings.

The world cannot understand the combination of these

two qualities. For want of truer comparison let us

liken him to a jealous woman—a whole souled uncultured

woman, strong in her passions and her love.

A sort of Parisian woman, now made desperate by a

long siege and an endless war.

A singular combination of circumstances laid his

life bare to me. I was a child and he was a child.

He permitted me to enter his heart.

As I write these opening lines here to-day in the

Old World, a war of extermination is declared against

the Modoc Indians in the New. I know these people.

I know every foot of their once vast possessions,

stretching away to the north and east of Mount Shasta.

I know their rights and their wrongs. I have known

them for nearly twenty years.

Peace commissioners have been killed by the

Modocs, and the civilized world condemns the

act. I am not prepared to defend it. This narrative

is not for its defence, or for the defence of

the Indian or any one; but I could, by a ten-line

paragraph, throw a bombshell into the camp of the

civilized world at this moment, and change the whole

drift of public opinion. But it would be too late to

Years and years ago, when Captain Jack was but

a boy, the Modocs were at war with the whites, who

were then scouring the country in search of gold.

A company took the field under the command of a

brave and reckless ruffian named Ben Wright.

The Indians were not so well armed and equipped

as their enemies. The necessities of the case, to say

nothing of their nature, compelled them to fight from

behind the cover of the rocks and trees. They were

hard to reach, and generally came out best in the

few little battles that were fought.

In this emergency Captain Wright proposed to meet

the chiefs in council, for the purpose of making a

lasting and permanent treaty. The Indians consented,

and the leaders came in. “Go back,” said Wright,

“and bring in all your people; we will have council,

and celebrate our peace with a feast.”

The Indians came in in great numbers, laid

down their arms, and then at a sign Wright and his

men fell upon them, and murdered them without

mercy. Captain Wright boasted on his return that

he had made a permanent treaty with at least a thousand

Indians.

Captain Jack was but a boy then, but he was a

true Indian. He was not a chief then. I believe he

was not even of the blood which entitles him to that

place by inheritance, but he was a bold, shrewd

united himself to a band of the Modocs, worked his

way to their head, and bided his time for revenge.

For nearly half a lifetime he and his warriors waited

their chance, and when it came they were not unequal

to the occasion.

They have murdered, perhaps, one white man to

one hundred Indians that were butchered in the

same way, and not so very far from the same spot.

I deplore the conduct of the Modocs. It will contribute

to the misfortune of nearly every Indian in

America, however well some of the rulers of the land

may feel towards the race.

With these facts before you, considering our

superiority in understanding right and wrong, and

all that, you may not be so much surprised at the

faithful following in this case of the example we set

the Modoc Indians, which resulted in the massacre,

and the universal condemnation of Captain Jack and

his clan.

To return to my reason for publishing this sketch

at this time. You will see that treating chiefly of

the Indians, as it does, it may render them a service,

that by-and-by would be of but little use, by instructing

good men who have to deal with this peculiar

people.

I know full well how many men there are on the

border who are ready to rise up and contradict

for the Indian, and have therefore given only a brief

account of the Ben Wright treachery and tragedy,

and only such an account as I believe the fiercest

enemy of the Indians living in that region admits to

be true, or at least, such an account as Ben Wright

gave and was accustomed to boast of.

The Indian account of the affair, however, which I

have heard a hundred times around their camp fires,

and over which they seemed to never tire of brooding

and mourning, is quite another story. It is dark

and dreadful. The day is even yet with them, a sort

of St. Bartholomew's Eve, and their mournful narration

of all the bloody and brutal events would fill a

volume.

They waited for revenge, a very bad thing for

Indians to do, I find; though a Christian king can

wait a lifetime, and a Christian nation half a century.

They saw their tribe wasting away every year;

every year the hordes of white settlers were eating

into the heart of their hunting grounds, still they lay

in their lava beds or moved like shadows through the

stormy forests and silently waited, and then when

the whites came into their camp to talk for peace, as

they had gone into the camp of the whites, they

showed themselves but too apt scholars in the bloody

lesson of long ago.

The scene of this narrative lies immediately about

tributaries flows from its snows on the north, and the

quiet Sacramento from the south. The Shasta

Indians, now but the remnant of a tribe at one time

the most powerful on the Pacific, live at the south

base of the mountain, while the Modocs and Pit

River Indians live at the east and north-east, with the

Klamats still to the north. The other sides and base

of the mountain is disputed territory, since the driving

out of its original owners, between settlers and

hunters, and the roving bands of Indians.

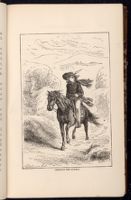

It was late in the fall. I do not know the day

or even remember the month; but I do know that I

was alone, a frail, sensitive, girl-looking boy, almost

destitute, trying to make my way to the mines of

California, and that before I had ridden my little

spotted Cayuse pony half way up the ten-mile trail

that then crossed the Siskiyou mountains, I met

little patches of snow; and that a keen, cold wind

came pitching down between the trees into my face

from the California side of the summit.

At one place I saw where a moccasin track was in

the snow, and leading across the trail; a very large

track I thought it was then, but now I know that

it was made by many feet stepping in the same impression.

My dress was scant enough for winter, and it was

chill and dismal. A fantastic dress, too, for one looking

between an Indian chief and a Mexican vaquero, with

a preference for colour carried to extremes.

As I approached the summit the snow grew deeper,

and the dark firs, weighted with snow, reached their

sable and supplie limbs across my path as if to catch

me by the yellow hair, that fell, like a school-girl's,

on my shoulders. Some of the little firs were covered

with snow, and were converted into pyramids

and snowy pillars.

I crossed the summit in safety, with a dreamy sort

of delight, a half-articulated “Thank God!” and

began to descend. Here the snow disappeared on the

south side of the mountain, and a generous flood of

sunshine took its place.

After a while I turned a sharp-cut point in the

trail, with dense woods hanging on either shoulder,

and an open world before me. I lifted my eyes and

looked away to the south.

Mount Shasta was before me. For the first time I

now looked upon the mountain in whose shadows so

many tragedies were to be enacted; the most comely

and perfect snow peak in America. Nearly a hundred

miles away, it seemed in the pure, clear atmosphere

of the mountains to be almost at hand. Above the

woods, above the clouds, almost above the snow, it

looked like the first approach of land to another

world. Away across a grey sea of clouds that arose

CROSSING THE SUMMIT

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A man on a horse is passing between two rock outcroppings. Wind blows the horse's mane and his shawl. In the background are mountains.]

stood, a solitary island; white and flashing like a

pyramid of silver! solemn, majestic and sublime!

Lonely and cold and white. A cloud or two about

his brow, sometimes resting there, then wreathed and

coiled about, then blown like banners streaming in

the wind.

I had lifted my hands to Mount Hood, uncovered

my head, bowed down and felt unutterable things,

loved, admired, adored, with all the strength of an

impulsive and passionate young heart. But he who

loves and worships naturally and freely, as all strong,

true souls must and will do, loves that which is most

magnificent and most lovable in his scope of vision.

Hood is a magnificent idol; is sufficient, if you do not

see Shasta.

A grander or a lovelier object makes shipwreck of

a former love. This is sadly so.

Jealousy is born of an instinctive knowledge of

this truth....

Hood is rugged, kingly, majestic, immortal! But

he is only the head and front of a well-raised family.

He is not alone in his splendour. Your admiration

is divided and weakened. Beyond the Columbia

St. Helen's flashes in the sun in summer or is folded

in clouds from the sea in winter. On either hand

Jefferson and Washington divide the attention; then

farther away, fair as a stud of fallen stars, the white

springs of the Willamette river;—all in a line—

all in one range of mountains; as it were, mighty

milestones along the way of clouds!—marble pillars

pointing the road to God.

Mount Shasta has all the sublimity, all the

strength, majesty, and magnificence of Hood; yet is

so alone, unsupported, and solitary, that you go

down before him utterly, with an undivided adoration—a

sympathy for his loneliness and a devotion

for his valour—an admiration that shall pass unchallenged.

I dismounted and stood in the declining sun, hat in

hand, and looked long and earnestly across the sea of

clouds. Now and then long strings of swans went

by to Klamat lakes. I could hear them calling to

each other. Far and faint and unearthly their echoes

seemed, and were as sounds that had lost their way,

and came to me for protection.

I looked and listened long but uttered not a sound;

strangely mute for a boy; but exclamation at such a

time is a sacrilege.

At last I threw a kiss across the sea of clouds, as

the red banners and belts of gold streamed from the

summit in the setting-sun, and turned, took up my

lariat, mounted, and proceeded down the mountain.

Should ever your fortune lead you to cross the

Chinese wall that divides the people of Oregon from

and ask for the old mountain trail. Take the direction

and stop at the top of what is called the first

summit of the Siskiyou mountains, for there you will

see to the left hand by the trail a pile of rocks high

as your head, put there to mark where a party fell a

few days after I passed the place.

Dismount and contribute a stone to the monument

from the loose rocks that lie up and down the

trail. It is a pretty Indian custom that the whites

sometimes adopt and cherish. I never fail to observe

it here, for this spot means a great deal to

me.

I uncover my head, take up a stone and lay it on

the pile, then turn my face to Mount Shasta and kiss

my hand, for the want of some better expression.

| CHAPTER I.

SHADOWS OF SHASTA. Unwritten history | ||