Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. | CHAPTER X.

TWO LITTLE INDIANS. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER X.

TWO LITTLE INDIANS. Unwritten history | ||

10. CHAPTER X.

TWO LITTLE INDIANS.

THE sunshine follows the rain. There was a

sort of general joyousness. The Prince was

now a king, it seemed to me. He had fought

a battle with himself, with fate against him; fought

it silent, patient and alone; he had conquered, and he

was glad.

The great hero is born of the long hard struggle.

Who cannot go down to battle with banners, with

trumps and the tramp of horses? Who cannot fight

for a day in a line of a thousand strong with the eyes

of the world upon him? But the man who fights a

moral battle coolly, quietly, patiently and alone, with

no one to applaud or approve, as the strife goes on

through all the weary year, and after all to have no

reward but that of his own conscience, the calm delight

of a duty well performed, is God's own hero.

He is knighted and ennobled there, when the fight

is won, and he wears thenceforth the spurs of gold

and an armour of invulnerable steel.

We went down again among the boulders in the

bed of the creek. The Prince swung his pick, I

shovelled the thrown-out earth, and the little Indians

would come and look on and wonder, and lend a

hand in an awkward sort of a way for a few minutes

at a time, then go back to the cabin or high up on

the hills in the sun, following whatever pursuit they

chose.

The Prince did not take it upon himself to direct

or dictate what they should do, but watched their

natural inclinations and actions with the keenest

interest.

He loved freedom too well himself to attempt to

fetter these little unfortunates with rules and forms

that he himself did not hold in too great respect;

and as for taxing them to labour, they were yet

weak, and but poorly recovered from the effects of

the famine on the Klamat.

Besides, he had no disposition to reduce them to

the Christian slavery that was then being introduced,

and still obtains, up about Mount Shasta, wherever

any of the Indian children survive.

The girl developed an amiable and gentle nature,

but the boy showed anything but that from the first.

He always went out of the cabin whenever strangers

entered, would often spend days alone, out of sight

of everyone, and stubbornly refused to speak a word

of English. At the end of weeks he was untamed

procured him a cheap suit of clothes, something after

the fashion of the miner's dress; but he despised it,

and would only wear his shirt with the right arm free

and naked, the red sleeve tucked in or swinging about

his body. He submitted to have his hair trimmed,

but refused to wear a hat.

His chief delight was, in pointing and making

faces at the Doctor's bald head, whenever that individual

entered, as he stood in the corner by his club;

but I never knew him to laugh, not even to smile.

The first great epoch of his civilized life was the

receipt of a knife as a gift from the Prince. It was

more to him than diamonds to a bride. He kept it

with him everywhere; slept with it always. It was

to him as a host of companions.

Sometimes he talked in the Indian tongue to the

girl, but only when he thought no one noticed or

heard him.

The girl was quite the other way. She took to

domestic matters eagerly, learned to talk in a few

weeks, after a fashion, and was most anxious to be

useful, and as near like an American as possible.

She had a singular talent for drawing. One day she

made an excellent charcoal picture of Mount Shasta,

on the cabin door, and was delighted when she saw

the Prince take pride in her work. She was eager

to do everything, and insisted on doing all the

cooking.

She had a great idea of the use of salt, and often

an erroneous one. For instance, one morning she

put salt in the coffee as well as in the beef and beans.

I think it was an experiment of hers—that she was

so anxious to please and make things palatable, she

put it in to improve the taste. I can very well

understand how she thought it all over, and said to

herself, “Now if a little pinch of this white substance

adds to the beans, why will it not contribute

to the flavour of the coffee?” Once she put sugar on

the meat instead of salt, but the same mistake never

happened twice.

I must admit that she was deceitful, somewhat.

Not willfully, but innocently so. In fact, had anything

of importance been involved, she would have

stood up and told the whole simple truth with a perfect

indifference to results. She did this once I know,

when she had done an improper thing, in a way that

made us trust and respect her. But she did so much

like to seem wise about things of which she was

wholly ignorant. When she had learned to talk she

one day pretended to Klamat to also be able to read

and understand what was written on the bills of the

butchers. Her ambition seemed to be to appear

learned in that she knew the least about. That is so

much like many people you meet, that I know you

are prepared to call her half-civilized, even in these

few weeks.

This sort of innocent deceit is no new thing, particularly

in women. And I rather like it. Go on to

one of the fashionable streets to-day in America, and

there you will find that the lady who has the least

amount of natural hair has invariably the largest

amount of artificial fix-ups on her head. This rule is

almost infallible; it has hardly the traditional exception

to testify to its truth.

In fact, does not this weakness extend even to man?

You can nearly always detect a bald-headed man,

even while his hat is on his head, by the display and

luxuriance of the hair peeping out from under his

hat. With the bald-headed man every hair is brought

into requisition, every hair is brushed and bristled

up into a sort of barricade against the eyes of the

curious. The few hairs seem to be marshalled up

for a fierce bayonet charge against any one who dares

suspect that the head which they keep sentry round

is bald. That man is bald and he feels it. Only

bald-headed men make this display of what hair they

have left.

And I am not sure but that nature herself is a

little deceitful. The dead and leafless oaks have the

richest growth of ivy, as if to make the world believe

that the trees are thriving like the bay. All about

the mouths of caves, all openings in the earth, old

wells and pits, the rankest growths abound, as if to

say, here is no wound in the breast of earth! here is

surface.

To go further into a new field. If a true woman

loves you truly she fortifies against it in every possible

way as a weak place in her nature. She tries to

deceive, not only the world, but herself. To keep

out the eyes of the inquisitive she would build a barricade

to the moon. She would not be seen to whisper

with you for the world. Yet if she loved you less,

she would laugh and talk and whisper by the hour,

and think nothing of it. I like such deceit as that.

It is natural.

The miners were at work like beavers. Up the

stream and down the stream the pick and shovel

clanged against the rock and gravel from dawn until

darkness came down out of the forests above them

and took possession of the place.

The Prince worked on patiently, industriously

with the rest, with reasonable success and first-rate

promise of fortune. The pent-up energies of the

camp were turned loose, and the stream ran thick

and yellow with sediment from pans, rockers, toms,

sluices and flumes. Never was such industry, such

energy, such ambition to get hold of the object of

pursuit and escape from the canon before another

winter set up an impassable wall to the civilized

world.

Spring came sudden and full-grown from the south.

Mexican seas, along the Californian coast, and drew

up to us between the rocky, pine-topped walls of the

Klamat.

At first she hardly set foot in the canon. The sun

came down to us only about noon-tide, and then only

tarried long enough to shoot a few bright shafts

through the dusk and dense pine-tops at the banks

of snow beneath, and spring did not like the place as

well as the open, sunny plains over by the city, and

toward the Klamat lakes. But at last she came to

take possession. She planted her banners on places

the sun made bare, and put up signs and land-marks

not to be misunderstood.

The balm and alder burst in leaf, and catkins

drooped and dropped from willows in the water, till

you had thought a legion of woolly caterpillars were

drifting to the sea. Still the place was not to be

surrendered without a struggle. It was one of

winter's struggles. He had been driven, day after

day, in a march of many a thousand miles. He had

retreated from Mexico to within sight of Mount

Shasta, and here he turned on his pursuer. One

night he came boldly down and laid hands on the

muddy little stream, and stretched a border of ice all

up and down its edges; spread frost-work, white and

beautiful, on pick, and tom, and sluice, and flume

and cradle, and made the miners curse him to his

night, lamb-tongue, Indian turnip and catella, and

took possession as completely as of old.

The sun came up at last and he let go his hold

upon the stream, took off his stamp from pick and

pan, and tom, and sluice and cradle, and crept in

silence into the shade of trees and up the mountain

side against the snow.

And now the spring came back with a double

force and strength. She planted California lilies, fair

and bright as stars, tall as little flag-staffs, along the

mountain side, and up against the winter's barricade

of snow, and proclaimed possession absolute through

her messengers, the birds, and we were very glad.

Paquita gathered blossoms in the sun, threw her

long hair back, and bounded like a fawn along the

hills. Klamat took his club and knife, drew his robe

only the closer about him in the sun, and went out

gloomy and sombre in the mountains. Sometimes

he would be gone all night.

At last the baffled winter abandoned even the wall

that lay between us and the outer world, and drew

off all his forces to Mount Shasta. He retreated above

the timber line, but he retreated not an inch beyond.

There he sat down with all his strength. He

planted his white and snowy tent upon this everlasting

fortress, and laughed at the world below him.

Sometimes he would send a foray down, and even in

peach, or apricot, for a hundred miles around his

battlement, whenever he may choose.

Now that the way was clear, immigrants and

new arrivals of all kinds began to pour into the

camp. The most noticeable was that of the new

Alcalde.

This Alcalde was appointed by the new commissioners

of the new county, and as might have been

expected, since the place brought neither profit nor

honour, was only a broad-cloth sort of a man. A

new arrival from the States, looking about for a

place where he could sit down and eat his bread

exempt from the primal curse. No doubt this little

egotist said to himself, “If there is a spot on earth

where God's great tribute-taker will not find me, it

is over at The Forks, on Humbug, and there will I

pitch my tent and abide.”

He had read just enough law to drive every bit of

common sense out of his head, and yet not enough to

get a bit of common law into it; except, perhaps, the

line which says that “Law is a rule of action prescribed

by the superior, which the inferior is bound

to obey.”

Being austere in his tastes, and feeling that he

had a dignity to sustain, he made friends with the

Doctor, and took up quarters in the Doctor's cabin.

As is the case with all small creatures, the Judge

and what was most remarkable, he wore a “stovepipe”

hat and a “boiled shirt;” the first that had

ever been seen in the camp. This was a daring

thing to undertake. The Judge, of course, had not

the least idea of his achievement and the risk he

incurred.

These men of the mountains always have despised

and perhaps always will despise a beaver hat. Why?

Here is food for reflection. Here is a healthy, well-seated

antipathy to an innocent article of dress, without

any discovered reason. Let the profound look

into this.

As for myself, I have looked into this thing, but

am not satisfied. The only reason I can give for this

enmity to the “tile” in the mountains of California,

is not that the miners hold that there is anything

wrong in the act or fact of a man wearing a beaver,

but because it invests the man with a dignity—an

artificial dignity, it is true, but none the less a

dignity—too far above that of the man who wears

a slouch or felt. The beaver hat is the minority,

the slouch hat is the majority; and, like all great

majorities, is a mob—a cruel, heartless, arrogant,

insolent mob, ignorant and presumptive. The beaver

hat is a missionary among cannibals in the California

mines. And the saddest part of it all is, that there

is no hope of reform. Tracts on this subject would

or by the splashing flume or dumping derrick!

Born of a low element in our nature is this antagonism

to the beaver hat; cruel as it is curious, selfish,

but natural.

The Englishman knows well the power and dignity

of a beaver hat. Go into the streets of London and

look about you. Surely some power has issued an

order not much unlike that of the famous one armed

Sailor—“England expects every man to wear a beaver

hat.”

But to return to this particular hat before us, it is

safe to say that no other man than the Judge in all

California could have brought into camp and worn

with impunity this hat.

It is true there was a universal giggle through the

camp, and it is likewise true that the Howlin' Wilderness

called out, “Oh, what a hat! Set 'em up!

Chuck 'em in the gutter! Saw my leg off!” and

so on, as the Judge passed that way the morning

after his arrival. But shrewd men at once took his

measure; saw that he was a harmless little egotist,

and in their hearts took his part in the hat question,

and set him up as a sort of wooden idol of the

camp.

It is not best to always seem too strong in the

presence of strong, good men. Man likes to pet

and patronize his fellow when he is weak. A strong

protect him. Strength challenges strength. The

combat of bulls on the plain! Possibly man inclines

to uphold the weak because there is no suggestion

of rivalry, but I do not think that. Here is room for

thought.

“It's all right, boys,” said six-foot Sandy, as he

stood at the bar of the Howlin' Wilderness, and

held out his glass for a little peppermint: “It's all

right, I tell you! He shall run a hat as tall as

Shasta if he likes, and let me set eyes on the shyster

that interferes. It's a poor camp that can't afford

one gentleman, anyhow.” And here he hitched up

his duck breeches, threw the gin and peppermint

down his throat, and wiping his hairy mouth on his

red sleeve, turned to the crowd, ready to “chaw up

and spit out,” as he called it, the first man who raised

a voice against the Judge and his beaver hat in all

The Forks.

Six-foot Sandy was an authority at The Forks. A

brawny and reckless miner—a sort of cross between

a first-class miner and a second-class gambler; a man

who vibrated between his claim up the creek and

the Howlin' Wilderness saloon. But he was a shrewd,

brave man, of the half-horse, half-alligator kind, and

was both feared and respected. After that the beaver

hat was safe at The Forks, and a fixture.

To illustrate the power and dignity of the beaver

hat even here, where reverence and respect for any

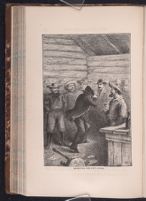

RECEIVING THE NEW JUDGE.

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A group of men stand around looking at a man in the center of the circle, who is slightly bent and has pulled his hat down over his face. In the foreground a stool or table is overturned and playing cards are on the floor. To the right, there is a table with a bottle and one man holds a glass.]

of, I may mention that a month or two after the

event described above, another beaver hat put in an

appearance at The Forks. There was not even a

protest. The man had sense enough to keep silent,

took a quiet game of “draw” with the boys at the

Howlin' Wilderness, and won at once the title of

Judge.

After dark the quiet game went on in the corner,

and Sandy came down from the claim.

“Who's that?” said Sandy to the bar-keeper, as he

threw his left thumb over his shoulder, and with his

right hand lifted his gin and peppermint.

“That? why that's Judge—Judge—why, the new

Judge.”

“Judge hell!” said Sandy, wiping his beard and

looking sharply under the hat rim. “I know him, I

do. He's a waiter over in a Yreka restaurant. I'll

go for him, I will. He is a fraud on the public.”

And he went up behind the man, as he sat there

on a three-legged stool, serenely leading out his ace

for his opponent's Jack.

“Come down!” said the new Judge, gaily; “come

down! I have you now! Come down!”

Sandy raised his hands, his great broad hands, like

slabs of pine, and brought them down on top of the

beaver hat like an avalanche. The hat shot down

and the head shot up, till it was buried out of sight

in the wrecked and ruined beaver.

The man sprung to his feet, thrust out his hands,

and jumped about like a boy in “Blind-man's-buff,”

and Sandy walked back to the bar, cool and unconcerned,

and ordered gin and peppermint.

The man at last excavated his nose, and took a

bee-line for the door, amid howls of delight from the

patrons of the Howlin' Wilderness. That is the

usual fate of beavers in the mines. They may be

respected, but they perish for all that.

Let a member of Congress, or even of the Cabinet,

go up into the mountains with a beaver, and ten to

one he would have it driven down over his nose.

He would have to stand it too; he would have to

laugh, call it a good joke, and treat “the boys” in

the bargain. After that they would call him a good

fellow, give him “feet” in an extension of the “Jenny

Lind” ledge, “Midnight Assassin,” or “Roaring Lion,”

and vote for him, if he should be a candidate for

office, to the last man.

I leave this question of the hat now to those wise

men of America who have rushed out upon the

frontier a pen in one hand, a telescope in the other,

and, viewing the Indian from afar off, decided in a

day that he was a bad and bloody character.

I leave this question to those teachers, with every

confidence that their capacities will prove equal to

the task. The subject is worthy such men, and the

men worthy such a subject.

| CHAPTER X.

TWO LITTLE INDIANS. Unwritten history | ||