Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. | CHAPTER XVI.

HOME. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XVI.

HOME. Unwritten history | ||

16. CHAPTER XVI.

HOME.

A PECULIARLY nervous man suffers from

a mental ailment as distinctly as from a

wound. He grows weak under the sense

of mental distress the same as an ordinary man does

from the loss of blood. Remove the cause of apprehension,

and he recovers the same as the wounded

man recovers. Free the mind, and you stop the flow

of blood. He grows strong again.

We moved on a little way that day, slowly, to be

sure, but fast enough and far enough to be able to

pitch our camp in a place of our own choosing, with

wood, water, and grass, the indispensable requisites

of a mountain camp, all close at hand.

To the astonishment of all, the Doctor unsaddled

his mule, gathered up wood, and was a full half-hand

at supper. At night he spread his own blankets,

looked to his pistols like an old mountaineer, and

seemed to be at last getting in earnest with life.

The next day, as we rode through the trees, he

across the trails, and chirped at the squirrels overhead.

How delightful it was to ride through the grass

and trees, hear the partridges whistle, pack and

unpack the horses, pitch the tent by the water, and

make a military camp, and talk of war; imagine

battles, shoot from behind the pines, and always, of

course, making yourself a hero. Splendid! I was

busy as a bee. I cooked, packed, stood guard, killed

game, did everything. And so we journeyed on

through the splendid forests, under the face of Shasta,

and over peaceful little streams that wound silently

through the grass, as if afraid, till we came to the

head-waters of the Sacramento.

Sometimes we saw other camps. White tents

pitched down by the shining river, among the scattered

pines; brown mules and spotted ponies feeding,

and half buried in the long grass; and the sound of

the picks in the bar below us all made a picture in

my life to love.

Once we fell in with an Indian party; pretty girls

and lively unsuspicious boys along with their parents,

fishing for salmon, and not altogether at war with

the whites. They treated us with great kindness.

At last we branched off entirely to ourselves, cutting

deep into the mountain as the winter approached,

looking for a home. The weak condition of the

journey to a close. We had taken a different route

from others, for good and sufficient reasons. The

trails and tracks of the hundreds of gold-hunters, who

had mostly preceded us some months, lay considerably

west of Mount Shasta, striking the head of the Sacramento

river at its very source. They had found only

a few bars with float gold, not in sufficient quantities

to warrant the location of a camp, and pushed

on to the mines farther south. Some, however,

returned.

We sometimes met a party of ten or more, all

well armed and mounted, ready to fight or fly as the

case might require. The usual mountain civilities

would be exchanged, brief and brusque enough, and

each party would pass on its way, with a frequent

glance thrown back suspiciously at our Indian

boy with his rifle, the invalid Doctor leaning on his

catenas, the Indian girl with her splendid hair and

face as bright as the morning, and the majestic figure

of the Prince. An odd-looking party was ours, I

confess.

Paquita knew every dimple, bend or spur in these

mountains now. The Prince entrusted her to select

some suitable place to rest. One evening she drew

rein and reached out her hand. Klamat stood his

rifle against a pine, and began to unpack the tired

little mule, and all dismounted without a word.

It was early sundown. A balm and a calm was

on and in all things. The very atmosphere was still

as a shadow and seemed to say, “Rest, rest!” We

were on the edge of an opening; a little prairie of

a thousand acres, inclining south, with tall, very tall

grass, and a little stream straying from where we

stood to wander through the meadow. A wall of

pines stood thick and strong around our little Eden,

and when we had unsaddled our tired animals and

taken the aparrajo from the little packer, we

turned them loose in the little Paradise, without even

so much as a lariat or hackamoor to restrain them.

The sun had just retired from the body of the

mountain, but it was evident that all day long he

rested here and made glad the earth; for crickets

sang in the grass as they sing under the hearthstones

in the cabins of the west, and little birds started up

from the edge of the valley that were not to be found

in the forest.

An elk came out from the fringe of the wood,

threw his antlers back on his shoulders with his

brown nose lifted, and blew a blast as he turned to

fly that made the horses jerk their heads from the

grass, and start and wheel around with fright. Brown

deer came out, too, as if to take a walk in the meadow

beneath the moon, but snuffed a breath from

the intruders and turned away. Bears came out two

by two in single file, but did not seem to notice us.

Some men say that the bear is deprived of the sense

of smell in the wild state. A mistake. He relies as

much on his nose as the deer; perhaps more, for his

little black eyes are so small that they surely are

not equal to the great liquid eyes of the buck, which

are so set in his head that he may see far and wide

at once. But the bear carries his nose close to the

ground, while that of the deer is lifted, and of course

can hardly smell an intruder in his dominions until

he comes upon his track. Then it is curious to observe

him. He throws himself on his hind legs,

stands up tall as a man, thrusts out his nose, lifts it,

snuffs the air, turns all around in his tracks, and

looks and smells in every direction for his enemy.

If he is a cub, however, or even a cowardly grown

bear, he wheels about the moment he comes upon

the track, will not cross it under any circumstances,

and plunges again into the thicket.

We had a blazing fire soon, and at last, when

we had sat down to the mountain meal, spread on

a canvas mantaro on the ground, each man on his

saddle or a roll of blankets, with his knife in hand,

Klamat looked at our limited supply of provisions,

and then pointed to the game in the meadow.

He pictured sun-rise, the hunt, the deer, the

crack of his rifle, and how he would come into camp

laden with supplies. All this, he gave us to understand,

would take place to-morrow, as he placed a

across his shoulder at the dark figures stealing

through the grass across the other side of our little

Eden.

The morning witnessed the fulfilment. Paquita

was more than busy all day in dressing venison, and

drying the meat for winter. The place was as full

of game as a park. No lonelier or more isolated place

than this on earth. We walked about and viewed

our new estates. The mules and ponies rolled in

the rich grass, or rested in the sun with drooping

heads and half-closed eyes.

Even the invalid Doctor seemed to revive in a

most sudden and marvellous way. He saw that no

white man's foot had ever trod the grasses of this

valley; that there we might rest and rest and never

rise up from fear. He could trust the wall of pine

that environed us. It was impassable. He stood

before an alder-tree that leaned across the babbling,

crooked little stream, and with his sheath-knife cut

this one word:—Home.

A little way from here Paquita showed us another

opening in the forest. This was a wider valley,

with warm sulphur and soda springs in a great

crescent all around the upper rim. Here the elk

would come to winter, she said; and hence we could

never want for meat. The earth and atmosphere

were kept warm here from the eternal springs; and

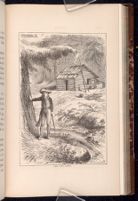

THE LOST CABIN.

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A man with a stick is standing next to a tree with his right hand resting on the tree. In the background there is a cabin with some long rods leaning up against it and more piled in front of the cabin. The cabin and man are in the woods and there is a creek next to the man.]

through.

This is the true source of the stream which the

white men call Soda; the proper Indian name of

which is Numken; and here we built our cabin,

reared a fortress against the approaching winter

without delay, for every night his sentries were

coming down bolder and bolder about the camp.

This was the famous “Lost Cabin.” It stood on

a hillside, a little above the prairie, facing the sun,

close to the warm springs, and on the very head of

the Numken, and was not unlike an ordinary miner's

cabin, except that the fireplace was in the centre

of the room instead of being awkwardly placed at

one end, where but few can get the benefit of the

fire. This departure was not without reason.

In the first place, the two Indians, constituting

nearly half of the voting population of our little colony,

insisted on it with a zeal that was certainly commendable;

and as they insisted on nothing else, it

was only justice to listen to them in this.

“By-and-by my people will come,” said Paquita,

“and then you will want an Indian fire, a fire that

they can sit down by and around without sending

somebody back in the cold.”

Again, you cannot build a cabin so strong with

one end devoted to a chimney, as if it is one solid

square body of logs. Then, it is no small task to

for a trowel and black mud for mortar.

All these things considered, we placed the fire in

the centre of the cabin on the earth-floor, and let

the smoke curl up and out through an opening in

the roof, as it always does and always will, in a

graceful sort of way, if you build a fire as an Indian

builds it.

The Doctor was getting strong again. As this

man grew strong in a measure, it is a little remarkable

that my sympathies were withdrawn proportionably.

I state this as a very remarkable fact. As the

pitiful condition of the Doctor daily grew less, his

crimes began to loom up and grow larger. They had

sunk down almost out of sight; but now as this man

began to lift up his hands to take part in the life

around him, I shrank back and said to myself, There

is blood on them—human blood.

No Indian had as yet, so far as we knew, discovered

us. Paquita had from the first, around

the fire, told her plans; how that as soon as she

should be well rested from the journey, and a house

was built and meat secured for the winter, she would

take her pony, strike a trail that lay still deeper in

the woods, and follow it up till she came to her

father's winter lodges.

How enthusiastically she pictured the reception.

into the village at sun-down, alone; the dogs would

bark a great deal at her red dress and her nice new

apparel. Then she would dismount and go straight

up to her father's lodge and sit down by the door.

The Indians would pass by and pretend not to see

her, but all the time be looking slily sideways, half-dead

to know who she was. Then, after a while,

some one of the women would come out and bring

her some water. Maybe that would be her sister.

If it was her sister, she would lift up her left arm

and show her the three little marks on the wrist,

and then they would know her and lead her into the

lodge in delight.

One fine morning she set forth on her contemplated

journey. I did not now like the place so

well. For the first time, I found fault with the

things around me. The forest was black, gloomy,

ghostly—a thing to be dreaded. Before, it was

dreamy, deep—a marvel, a something to love and

delight in. The cabin, that had been a very palace,

was now so small and narrow, it seemed I would

suffocate in the smoke. The fires did not burn so

well as they did before. Nobody could build a fire

like Paquita.

Back from our cabin a little way were some grand

old bluffs, topped with pine and cedar, from which

the view of valley, forest, and mountain, was all that

from the warm springs, the waters of the valley came

together and went plunging all afoam down the

canon, almost impassable even for footmen. Here

we found fine veins of quartz, and first-rate indications

of gold both in the rock and in the placer.

The Prince and the Doctor revived their theories on

the origin of gold, and had many plans for putting

their speculations to the test.

Klamat was never idle, yet he was never social.

There was a bitterness, a sort of savage deviltry, in

all he did. A fierce positive nature was his, and

hardly bridled at that.

Whether that disposition dated further back than

a certain winter, when the dead were heaped up and

the wigwams burned on the banks of the Klamat, or

whether it was born there of the blood and bodies in

the snow, and came to life only when a little, naked,

skeleton savage sprung up in the midst of men with

a club, I do not pretend to say, but I should guess

the latter. I can picture him a little boy with bow

and arrows, not over gentle it is true, but still a

patient little savage, like the rest, talking and taking

part in the sports, like those around him. Now he

was prematurely old. He never laughed; never so

much as smiled; took no delight in anything and

yet refused to complain. He took hold of things,

did his part, but kept his secrets and his sorrows to

himself, whatever they may have been.

Klamat never alluded to the massacre in any way

whatever. Once, when it was mentioned, he turned

his head and pretended not to hear. Yet, somehow

it seemed to me that that scene was before him every

moment. He saw it in the fire at night, in the forest

by day. There are natures that cannot forget if they

would. A scene like that settles down in the mind;

it takes up its abode there and refuses to go away.

His was such a nature.

In fact, Indians in the aggregate forget less than

any other people. They remember the least kindness

perfectly well all through life, and a deep wrong is

as difficult to forget. The reason is, I should say,

because the Indian does not meet with a great deal

of kindness as he goes through life. His mind and

memory are hardly overtaxed, I think, in remembering

good deeds from the white man.

Besides, their lives are very monotonous. But

few events occur of importance outside their wars.

They have no commercial speculations to call off the

mind in that direction; no books to forget themselves

in, and cannot go beyond the sea, and hide in old

cities, to escape any great sorrow that pursues them.

So they have learned to remember the good and the

bad better than do their enemies.

This cabin of ours in the trees on the rim of the

clearing grew soon to be a sacred place to all. Here

was rest absolute, unqualified repose. Eight-hour

fashion of the country, did not concern us here.

There were no days in which we were required to

remain in to receive company, no days in which we

were expected to make calls. We named the cabin

the “Castle,” and the Doctor cut out wooden cannon,

mounted them on pine stumps before the door as on

little towers, and turned them on the world below.

| CHAPTER XVI.

HOME. Unwritten history | ||