Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. | CHAPTER XI.

“A MAN FOR BREAKFAST.” |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XI.

“A MAN FOR BREAKFAST.” Unwritten history | ||

11. CHAPTER XI.

“A MAN FOR BREAKFAST.”

NOW that we have got a Judge,” said Sandy

one day, “why not put him to work?”

There had been a pretty general feeling

against those who took part in the murder of the

Indians the last winter kept alive by the miners, and

Sandy, who was always boiling over on some subject,

and was brimfull of energy, went and laid the case

before the Judge and instituted a prosecution. Here

was a sensation! The court sent a constable to

arrest a prisoner with a verbal warrant, and the man

came into Court; the Howlin' Wilderness, followed

by half the town, gave verbal bonds for his

appearance next Saturday, and the Court adjourned

to that day.

Sides were taken at once. The idlers of course

all taking sides with the prisoner; the miners mostly

going the other way. Sandy took it upon himself

to prosecute. He could hardly have been in earnest,

yet he seemed to be terribly so. The assassins were

friends with the Judge, and intimidating all who

dared express sympathy with the Indians. The

miners, with the exception of Sandy, were rather indifferent.

They knew very well that this weak

little egotist would only make a farce of the affair,

even though he had capacity to enter a legal committal.

The giant Sandy, however, held his own

against all the town and promised a lively time.

The Indian boy came home that night beaming

with delight. His black eyes flashed like the eyes of

a cat in the dark. I had thought him incapable of

excitement. He had always seemed so passive and

sullen that we had come to believe he had no life or

passion in him.

He talked to Paquita eagerly, and made all kinds

of gestures; put his fingers about his neck, stabbed

himself with an imaginary knife, threw himself towards

the fire, and shot with an imaginary gun at

an imaginary prisoner. Would he be hung, stabbed,

burnt or shot? The boy was so eager and excited, that

once or twice he broke out into pretty fair English

at some length, the first I had ever heard him utter.

The Doctor, as I said, was unpopular. In fact,

doctors usually are in the mines. Whether this is

because nine-tenths of those who are there are frauds

and impostors, or whether it is because miners give

open expression to a natural dislike that all men

submit ourselves some day, I do not pretend to

say.

Even the Indian boy disliked the Doctor bitterly,

and one day flew at him, without any cause, and

clutched a handful of hair from his thin and half-bald

head. The Judge, too, disliked the Doctor, and only

the evening before the trial some one, passing the

cabin, heard the Judge call the Doctor a fool to his

teeth.

That was a feather in the Judge's hat, in the eyes

of The Forks, but a bad sign for the Doctor. The

Doctor should have knocked him down, said The

Forks.

The day of trial came, and Sandy, in respect for

the Court and the occasion, buttoned up his flannel

shirt, hid his hairy bosom, and gave over his gin and

peppermint during all the examination.

The prisoner was named “Spades.” Whether it

was because he looked so like the black, squatty

Jack of Spades I do not know; but I should say he

was indebted to his likeness to that right or left

bower for his name.

There was not the slightest doubt that he had

deliberately murdered two or three Indian children,

butchered them, as they crouched on the ground and

tried to hide under the lodges, with his knife, on the

day of the massacre; but there were grave doubts as

been pretty plainly told that he must not hold the

man to answer.

A low, wretched man was this—the lowest in the

camp; but he stood between others of a more respectable

character and danger. His fortune in the matter

was a prophecy of theirs. The prisoner was nearly

drunk as he took his seat on a three-legged stool

before the Judge in the Howlin' Wilderness. He sat

with his hat on. In fact, miners, in the matter of

wearing hats, would make first-class Israelites.

“Ef I ain't out o' this by dark,” said Spades, as

he jerked his head over his shoulder and spirted a

stream of amber at the back-log, “I'll sun somebody's

moccasins, see if I don't.” And he looked

straight at the Judge, who settled down uneasily in

his seat, and placed his beaver hat on the table between

himself and the prisoner as a sort of barricade.

Two or three gamblers, good enough men in

their way, acted as attorneys for Spades. They at

once turned themselves loose in plausible, if not

eloquent, speeches against the treacherous savage.

Sandy now introduced his witness for the prosecution.

This man told how Spades had butchered the

babes down on the Klamat, in detail; and then

others were called and did the same. It was a clear

case, and Sandy was delighted with his prosecution.

The other side did not ask any questions. The

then one of them got up, took the stand, and gravely

asserted that on that day, and at the very moment

described, he was playing poker with Spades at two

bits a corner in the Howlin' Wilderness. Then

another arose with the same account; and then

another. It was the clearest alibi possible.

Sandy said nothing, and the case was closed. He

looked black across the table at the defence, and then

went up to the bar, and called for gin and peppermint,

alone.

This was the first attempt to introduce law practice

at The Forks, and no wonder that it did not

work well, and that some things were forgotten. All

were new hands—Court, counsel, and nearly all

present, here witnessed their first trial.

Poor Sandy had forgotten to have his witnesses

sworn, and the Court had not thought of it.

The testimony being all in, the Court proceeded

solemnly to sum up the case. In conclusion, it

said, “You will observe that, as a rule, the further

we go from the surface of things the nearer we get

to the bottom.” This brought cheers and waving of

hats from the Howlin' Wilderness, and the Court repeated,

“I am free to say that the Court has gone

diligently into the depths of this case, and that, as a

rule, the further you get from the surface of things

the nearer you get to the bottom. The case looked

Court has gone to the bottom of the matter, and he

is now white as snow.”

“Hear! hear! hear!” shouted a man from Sydney,

who always hobbled a little as if he dragged a chain

when he walked.

“Snow is good!” said a miner between his

teeth, as he looked at the black visage of the

prisoner.

“You see,” continued the Judge, “that things are

often not so black as they first appear, particularly

if they are only fairly washed.”

“Particularly if they are white-washed!” said

Sandy, as he swallowed his gin and peppermint and left

the saloon in disgust.

All this time a tawny little figure had stood back

in the corner unseen, perhaps, by any one. It was

Klamat with his club. He had watched with the

eyes of a hawk the whole proceeding. He had drank

in every sentence, and had never once taken his eyes

from the Court or the prisoner.

At last, when the Judge decreed the prisoner free,

and the Court adjourned, and all ranged themselves

in a long, single file before the bar, calling out

“Cocktail,” “Tom-and-Jerry,” “Brandy-smash, “Ginsling,”

“Lightning straight,” “Forty rod,” and so

on, he slipped out, looking back over his shoulders,

with his thin lips set, and his hand clutching a knife

under his robe.

That evening the Judge was again belabouring the

Doctor with his tongue, which had been made more

than ordinarily loose and abusive by the single-file

drilling process that had been repeated at the

Howlin' Wilderness in the celebration of Spades'

acquittal.

“That little Doctor 'll put a bug in his soup for

him yet, see 'f he don't,” said some one that evening

at the saloon, when the man who had heard the

Judge's abuse had finished reciting it.

“All right, let him,” said a man, who stood stirring

his liquor with a spoon, in gum-boots and with a gold-pan

under his left arm. “All right, let him;” said

the bearded sovereign, as he threw back his head

and opened his mouth. “It's not my circus, nor

won't be my funeral;” and he wiped his beard and

went out saying to himself:—

Thar's no dog of mine thar.”

The Prince, with that clear common-sense which

always came to the surface, had foreseen the whole

affair so far as the trial was concerned, and had

remained at home hard at work in the claim; I told

him all that had happened, and he only shrugged

his shoulders.

The next morning the butcher shouted down from

the cabin as he weighed out the steaks: “A man for

breakfast up in town, I say! a man for breakfast up

“Who?”

“The Judge!”

The man had been stabbed to death not far from

his own door, some time in the night, perhaps just

before retiring. There were three distinct mortal

wounds in the breast. There had evidently been a

short, hard struggle for life, for in one hand he

clutched a lock of somebody's hair. There was no

mistake about the hair. That long, soft, silken, half

curling, yellow German hair of the Doctor's, that

grew on the sides of his naked head—there was not

to be found another lock of hair like this in the

mountains.

The dead man had not been robbed. That was a

point in the Doctor's favour. He had been met in

the front, had not been poisoned, or stabbed or shot

in the back; that was another very strong point in

the Doctor's favour.

In some of the northern states of Mexico, particularly

at Guadalajara, I remember some years ago

it was a pretty good defence for a man charged with

murder, if he could prove that he had not plundered

the dead, and that he had met him from the face like

a man. These Mexicans held that man is not naturally

vicious or bloodthirsty, and will not take life

without cause: that if he did not murder a man to

rob him, he had some secret and perhaps sufficient

right; then if, added to these, he met his man like a

man and he came off victor, although he slew the

man, the law for that would hardly take his life.

There was something of this feeling in the camp

now. However, if there had been an alcalde at The

Forks, there is no doubt the Doctor had been at

once arrested; but as there was nothing of the kind

nearer than a day's ride, nothing was done. Besides,

the Judge had made himself particularly odious to

the miners, and gamblers are the last men in the

world to meddle with the law. They settled their

suits with steel across a table, or with little bull-dog

deringers around a corner. Sometimes they have a

six-shooter war dance in the streets, if the misunderstanding

is one in which many parties are concerned.

As a rule, a funeral in the mines is a mournful

thing. It is the saddest and most pitiful spectacle I

have ever seen. The contrast of strength and weakness

is brought out here in such a way that you

must turn aside or weep when you behold it. To

see those strong, rough men, long-haired, bearded

and brown, rugged and homely-looking, with something

of the grizzly in their great, awkward movements,

now take up one of their number, straightened

in the rough pine box, in his miner's dress, and

carry him up, up on the hill in silence—it is sad

beyond expression.

He has come a long way, he has journeyed by

land or sea for a year, he has toiled and endured,

and denied himself all things for some dear object at

home, and now after all, he must lie down in the

forests of the Sierras, and turn on his side and

die. No one to kiss him, no one to bless him,

and say “good-bye,” only as a woman can, and

close the weary eyes, and fold the hands in their

final rest: and then at the grave, how awkward—

how silent! How they would like to look at each

other and say something, yet how they hold down

their heads, or look away to the horizon, lest they

should meet each other's eyes. Lest some strong man

should see the tears that went silently down from

the eyes of another over his beard and on to the

leaves.

But the Judge had no such burial as this. Sandy

was on a spree, and the gamblers placed Spades at

the head of the funeral. They had no respect for

the man and kept away. Spades was chief mourner,

and the poor little man was laid alone on the hill-side,

with hardly enough in attendance to do the last

offices for the dead.

That night Spades entered the Howlin' Wilderness

wearing a beaver hat. Sandy saw this, set

down the glass of gin and peppermint untouched,

and went straight up to the man. He seized him

by the throat and shook him till his teeth smote and

he picked up the hat reverently and respectfully as

his condition would allow, and laid it gently on the

roaring pine-log fire. That was the last of the first

beaver hat of Humbug.

The Doctor appeared out of place in this camp from

the first. Every one seemed to feel that—perhaps

no one felt it more keenly than himself.

There are people, it seems to me, who go all

through life looking for the place where they belong

and never finding it. This to me is a very sad

sight. They seem to fit in no place on top of the

earth.

The general feeling of dislike that had always

been observed, now became one of contempt. No one

noticed or spoke to him now. He came to hold

down his head very soon, and to shun people instinctively

since they seemed to wish to shun him.

I am bound to confess, right here, that after this

murder, when the whole camp seemed turned against

this shy, shrinking, silent man, when he was despised

by all, when no one would share the path with him,

but would make him stand aside and leave the trail

as if he had been an Indian or a Chinaman, I began

to sympathize with him. When the world pointed

its finger and set the mark of Cain upon the man, I

began to like him.

This, you say, seems to you remarkable. It is

to mention it.

There was now an expression in this man's face that

I had not seen before. A sort of weary, tired look it

was, that was pitiful. An idea took possession of

me that he had grown tired in his journey from

place to place in the world, looking for the place

where he belonged, for a sort of niche where he

would fit in, and which he had never yet found.

There are men who sit in a community like a

centre gem in a cluster of diamonds, and who

cannot be taken away without deranging and

marring the whole. The place of such a man

is vacant till the last one of the cluster of which he

forms the centre goes down in the dust.

There are others, again, who grow on the side or

even in the centre of a community, like a great wart

or wen. They sap its strength, they stop its growth,

they poison it thoroughly, and it dies: a miserable,

contemptible community, all through that one bad

man.

But the Doctor was neither of these. He had

never yet found his place, had never yet taken root

or hold anywhere, but had been blown or rolled or

thrown or pitched or shuttle-cocked about, it seemed

to me, from the beginning of his life; whenever that

may have been. A sort of sour, dried-up apple, that

no one would eat, yet an apple that no one would

care to pitch out of the window.

I had always hated and feared the man till now.

The universal dislike, however, aroused a sort of

antagonism in my nature, that always has, and I

expect always will, come to the surface on such

occasions on the side of the poor or much despised,

perfectly regardless of propriety, self-interest, or any

consideration whatever.

If a man has succeeded and is glad, let him go his

way. What should I have to do with him? My lot

and my life thus far have been with the poor and the

lonely, and so shall be to the end. They can understand

me.

And maybe, often, there is a kind of subtle

wisdom in this view of men. I think it is born of

the fact that your ostentatious, prosperous man,

your showy rich man of America, is so very, very

poor, that you do not care to call him your neighbour.

It is true he has horses and houses and

land and gold, but these horses and houses, and

lands and coins, are all in the world he has. When

he dies these will all remain and the world will

lose nothing whatever. His death will not make

even a ripple in the tide of life. His family, whom

he has taught to worship gold, will forget him in

their new estates. In their hearts they will be glad

that he is gone. They will barter and haggle with

the stone-cutter toiling for his bread, and for a

starve-to-death price they will lift a marble shaft

cold, and soulless!

Poor man, since he took nothing away that one

could miss, what a beggar he must have been. The

poor and unhappy never heard of him: the world has

not lost a thought. Not a note missed, not a word

was lost in the grand, sweet song of the universe

when he died.

Save us from such men. America is full of them.

She boils over with them in a sort of annual eruption.

She throws them over the sea into abbeys and

sacred places, with their hats on; they are howling,

hoarser than jackals, up and down the Nile and

over and away towards Jerusalem.

It was remarkable how suddenly the Indian

children sprung up with the summer. No one could

have recognized in this neat, modest, sensitive girl,

and this silent, savage-looking boy, who sometimes

looked almost a man, the two starved, naked little

creatures of half a year before.

There was a little lake belted by wild red roses

and salmon berries, and fretted by overhanging ferns

under the great firs that shut out the sun save in

little spars and bars of light that fell through upon

a bench of the hills; a sort of lily pond, only half

a pistol shot across, at the bottom of a waterfall, and

clear as sunshine itself. Here Paquita would go

often and alone to pass her idle hours. I chanced

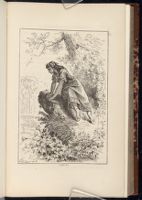

PAQUITA.

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. An Indian woman its on a outcropping of rock and leans on her arms looking out onto some water below her. She is wearing a dress and mocassins and has flowers in her hair. ]

and looking into the water as she moved forward,

now and then back, across her shoulder, as a maiden

in a glass preparing for a ball. She had just been

made glad with her first new dress—red, and

decorated with ribbons, made gay and of many

colours. The poor child was studying herself in the

waters.

This was not vanity; no doubt there was a deal of

satisfaction, a sort of quiet pride, in this, but it was

something higher, also. A desire to study grace, to

criticize her movements in this strange and to her

lovely dress, and learn to move with the most

perfect propriety. She practiced this often. The

finger lifted sometimes, the head bowed, then the

hands in rest and the head thrown back, she would

walk back and forth for hours, contemplating herself

and catching the most graceful motion from the

water.

What a rich, full, and generous mouth was hers—

frank as the noon-day. Beware of people with small

mouths, they are not generous. A full, rich mouth,

impulsive and passionate, is the kind of mouth to

trust, to believe in, to ask a favour of, and to give

kind words to.

There are as many kinds of mouths as there are

crimes in the catalogue of sins. There is the mouth

for hash!—thick-lipped, coarse, and expressionless, a

Bah! Then there is the thin-lipped, sour-apple

mouth, sandwiched in between a sharp chin and thin

nose. Look out!

There are mischievous mouths, ruddy and full of

fun, that you would like to be on good terms with if

you had time, and then there is the rich, full mouth,

with dimples dallying and playing about it like

ripples in a shade, half sad, half glad—a mouth to

love. Such was Paquita's. A rose, but not yet

opened; only a bud that in another summer would

unfold itself wide to the sun.

| CHAPTER XI.

“A MAN FOR BREAKFAST.” Unwritten history | ||