26. CHAPTER XXVI.

A BLOODY MEETING.

I COULD not endure to remain in camp. I

went down the river and rested there, and

thought what I now should do. I began to

recover strength and resolution. I said, if I was

right at first I am still right. I resolved to return;

but no Indian would venture to go back again, and

I went alone. Leaving my horse on a ranch I entered

Yreka, and took the stage to Deadwood. I at once

went to the Indian camp, and told them of our loss.

They, superstitious like the others, resolved to gather

up their effects and supplies and return through the

mountains to the McCloud.

After seeing my old white friends a few hours, I

was told that Bill Hirst, the famous man-killer and

desperado, with whom I had unfortunately previously

become involved, had accused me of being with the

Indians, and also taking, or having a hand in taking,

his horse.

I cleaned and prepared my pistols for this man.

At another time I might have been disposed to

avoid this fellow. Now I wanted to meet him. It

was not particularly for what he had said or done,

but he had long been the terror of the camp; and

with something of a spirit of chivalry and determination

to revenge some wrongs of men less ready to

fight, I quietly resolved to meet this man in mortal

combat. Of course my own desperate condition

contributed to make me reckless, and tenfold more

ready to resent an insult. If I bore myself well

in the scene that followed it was owing more to that,

perhaps, than to manly valour.

As the men gathered into Deadwood camp, Hirst

among the others, I entered the main saloon and called

the boys to the bar in a long red and blue-shirted

line. We took a drink, and then, after the fashion of

the time, I drew a revolver, and declared myself chief

of the town. This is the way a man proceeded in

those days who had a wrong to avenge. If his

enemy was in camp this was his signal to “heel”

himself and come upon the ground. I passed from

one saloon to another, making this same declaration

until toward midnight. While standing with a knot

of miners at the bar of Dean's billiard saloon,

Hirst entered the far end of the establishment; a tall,

splendid fellow, with his hat pushed far back from his

brow, flashing eyes, and a pistol in his hand.

Not a sound was heard but the resolute tread of

Hirst, as he advanced partly toward me and partly

toward the billiard table, while the men at play

quietly fell back and left the red and white balls

dotting the green cloth.

Those around me sidled away right and left,

and I stood alone. Hirst advanced to the table,

darting his restless, keen eyes at me every second,

and, standing against and leaning over the table, all

the time watching me like a cat, he punched the

billiard balls savagely with the muzzle of his pistol.

He then drew back from the table, tossed his head,

whistled something, and moved in my direction.

My hand was on my pistol. The hammer was

raised and my finger touched the trigger; but Hirst,

without advancing further or saying a word, quietly

turned out at a side door and I saw no more of him

that night.

I had done nothing, said nothing, but answering

to the rough code and etiquette of the camp, the

victory was mine; for when a man enters a room

where his antagonist is, it is his place to make the

first demonstration. This Hirst did not openly do;

still no doubt he had done enough to satisfy his ambition

for that evening, and it was evident the end was

not yet. It was also evident, brave and reckless as

he was, that he sought rather to maintain his reputation

for recklessness than to meet me as he had met

so many others.

I went down the creek that night, after this event,

with my white friends, the gentlemen who kept

the library, and retired.

The next morning we took a walk about the

mining claim, returned, sat down in the shadow of

the cabin with a few friends who had gathered in,

and were talking over the little event of the evening

before, when Hirst and an officer came riding gaily

down the road, followed by several other gentlemen

on horseback, who were coming down to see the

result of a second meeting.

The cabins stood on the opposite side of the

stream from the road, and ditches had to be crossed

by the horsemen to reach us. The officer and Hirst—

both splendid horsemen as well as famous pistolshots—leapt

the ditches and came darting over; but

the others, whoever they were, as they had an open

view from where they stood, felt that they were

quite near enough, and reined their horses.

The men I was then with, and with whom I had

spent the night, were the most peaceful, noble, and

gentlemanly fellows in the camp, and I had no wish

to make their cabins the scene of a tragedy. I

was equally unwilling to submit to Hirst in any form

or manner, and hastily shaking hands with my

friends as the men advanced up the hill, I made off

up the mountain, perhaps fifty yards in advance of

the horsemen, and on foot.

Pistols flourished in the air, the men started forward

almost upon me, and it looked as if I was to be

shot down and trampled under foot. The hill side

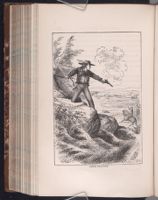

[ILLUSTRATION]

PISTOL PRACTICE.

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A man is standing on a rock outcropping overlooking a plain. One knee rests on some rocks and he holds onto a tree branch with his right hand. In his left hand he is aiming a pistol at a man on a horse in the valley below. The man on the horse is aiming a pistol at the man on the rock outcropping. There is another figure in the background of the plain, and there are two cabins in the distance.]

was steep and rocky, and the mettlesome little

Mexican horses refused to rush upon me across the

steep and broken ground, but began to spin round

like tops, and would not advance up the hill.

Some hard, iron-clad oaths, and then shot after

shot. I turned, drew a pistol, and the battle commenced

in earnest. The officer was unhorsed, and

lay bleeding on the ground from a frightful wound,

while Hirst, further down the hill, could only fire

random shots over the head of his restless and

plunging horse. It lasted but a few moments.

These men were both famous as pistol shots; but

they were not, here, equal to their reputation,

and that was because they were shooting on a range

they had never yet tried. They had only practised

on the level ground or in a well-arranged gallery,

and when it came to shooting up hill they were

helpless; and so it often happens with others. There

are other men, again, who are dead pistol shots

when allowed to draw deliberately and take aim

slowly and fire at leisure; but when compelled to

use the pistol instantly in some imminent peril,—the

only time they are ever really required to use it,—

they are slow, awkward, and embarrassed.

Let us for a moment follow the fortunes of these

two men before us: the one lying bleeding on the

ground, and the other flying down across the hill,

firing, and trying to hold his spirited horse to the

work.