Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. | CHAPTER XIX.

THE INDIANS' ACCOUNT OF THE CREATION. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER XIX.

THE INDIANS' ACCOUNT OF THE CREATION. Unwritten history | ||

19. CHAPTER XIX.

THE INDIANS' ACCOUNT OF THE CREATION.

I NOW became almost thoroughly an Indian.

The clash and struggle of the world

below had ground upon my nerves, and I

was glad to get away. Perhaps by nature I inclined

to the dreamy and careless life of the Arabs of

America; certainly my sympathies had always been

with them, and now my whole heart and soul entered

into the wild life in the forest. In fact from the first

few months I had spent with these people—a sort of

prisoner—I had a keen but inexpressed desire to be

with them and them alone.

Now my desire was wholly gratified. I had seen

my last, my only friend depart, and had shut the

door behind him with a slam—a sort of fierce delight

that I should be left alone in the wilderness.

No more plans for getting money; no more reproach

from fast and clever men who managed the

lower world; no more insults from the coarse and

insolent; no more bumping of my head against the

civilization;—nothing, it seemed to me now, but

rest, freedom, absolute independence.

Did I dread and fear the primeval curse that God

has put upon all men, and so seek to hide away from

Him in the dark deep forests of Shasta?

I think not. I think rather that all men have

more or less of the Arab in their natures; and but

for the struggles for gold, the eddies and currents of

commerce, and the emulation of men in art, and the

like, we should soon become gipsies, Druids, and

wanderers in the wild and fragrant woods that would

then repossess the lands.

Maybe after a while, when the children of men are

tired and weary of the golden toy they will throw it

away, rise up and walk out into the woods, never

more to return to cities, to toil, to strife, to thraldom.

But the Indian's life to an active mind is monotonous,

and so I found it there; listless, dull and

almost melancholy. We rode, we fished, we hunted,

and hunted, and fished, and rode, and that was nearly

all we could do by day. If, however, we had no

intense delights we had no great concern. We

dreamed dreams and built castles higher than the

blue columns of smoke that moved towards the

heavens through the dense black boughs above. And

so the seasons wore away.

Under all this, of course, there was another

loves, and as they have but little else, these fill up

most of their lives. That I had mine I do not deny;

and how much this had to do with my remaining

here I do not care to say. Nor can I bring my will

to write of myself in this connection. These things

must remain untold. They were sincere then, and

shall be sacred now.

At night, when no wars or excitement of any kind

stirred the village, they would gather in the chief's

or other great bark lodges around the fires, and tell

and listen to stories; a red wall of men in a great

circle, the women a little back, and the children still

behind, asleep in the skins and blankets. How silent!

You never hear but one voice at a time in an Indian

village.

The Indians say the Great Spirit made this mountain

first of all. Can you not see how it is? they

say. He first pushed down snow and ice from the

skies through a hole which he made in the blue

heavens by turning a stone round and round, till

he made this great mountain, then he stepped out

of the clouds on to the mountain top, and descended

and planted the tree all around by putting his finger

on the ground. Simple and sublime!

The sun melted the snow, and the water ran down

and nurtured the trees and made the rivers. After

that he made the fish for the rivers out of the small

some leaves which he took up from the ground

among the trees. After that he made the beasts out

of the remainder of his stick, but made the grizzly

bear out of the big end, and made him master over

all the others. He made the grizzly so strong that

he feared him himself, and would have to go up on

the top of the mountain out of sight of the forest to

sleep at night, lest the grizzly, who, as will be seen,

was much more strong and cunning then than now,

should assail him in his sleep. Afterwards, the

Great Spirit wishing to remain on earth, and make

the sea and some more land, he converted Mount

Shasta by a great deal of labour into a wigwam, and

built a fire in the centre of it and made it a pleasant

home. After that his family came down, and they

all have lived in the mountain ever since. They say

that before the white man came they could see the

fire ascending from the mountain by night and the

smoke by day, every time they chose to look in that

direction.

This, I have no doubt, is true. Mount Shasta is

even now, in one sense of the word, an active volcano.

Sometimes only hot steam, bringing up with

it a fine powdered sulphur, staining yellow the snow

and ice, is thrown off. Then again boiling water,

clear at one time and then muddy enough, boils up

through the fissures and flows off into a little pool

unsettled and uncertain. Sometimes you hear most

unearthly noises even a mile from the little crater, as

you ascend, and when you approach, a tumult like a

thousand engines with whistles of as many keys;

then again you find the mountain on its good behavior

and sober enough.

Once it was thought a rare achievement to make

the ascent of Mount Shasta; now I find that almost

every summer some travellers and residents make

the ascent. This must not be undertaken, however,

when the arid sage brush plains of the east are

drawing the winds across from the sea. You would

at such a time be blown through the clouds like a

feather.

Two days only are required to make the crater

from the ranches in Shasta valley at the north

base of the mountain. The first day you ride

through the dense forest—a hard day's journey indeed—up

to the snow line, where you sleep, leave

your horses, and with pike and staff confront the ice

and snow.

I ascended this mountain the last time more than

fifteen years ago. It was soon after I first returned

to the Indians. I acted as guide for some travelling,

solemn, self-important-looking missionaries in black

clothes, spectacles and beaver hats. They gave me

some tracts, and paid me for my services in prayers

unpleasant that I never had courage or desire to

undertake it again.

There is but one incident in it all that I have ever

recalled with pleasure. I had come out of the forest

like a shadow, timid, shrinking, sensitive, to these

men: like an Indian, eager to lead them, to do them

any service for some kind words, some sympathy,

some recognition from these great, good men, wise

and learned, who professed to stand so near the

throne eternal, who were so anxious for the heathen.

I led and fed and watered and groomed their horses.

I watched while they slept, spread their blankets

beneath the trees on the dry soil, folded and packed

them, headed the gorges, shunned the chaparral

and bore on my own shoulders all the toils, and took

on my own breast all the dangers of the day. I

found them the most sour, selfish, and ungrateful

wretches on earth. But I led them to the summit

—two of them only—panting, blowing, groaning at

every step. The others had sat down on blocks of

ice and snow below. These two did not remain a

moment. They did not even lift their eyes to the

glory that lay to the right or to the left. What to

them was the far faint line of the sea to the west;

the long white lakes that looked like snow drifts, a

hundred miles away to the east? Had they not

been on the summit? Had they not said a prayer

say, to report, to write about? Was all this not

enough?

Hastily, indeed, they muttered something, hurriedly

drew some tracts from their pockets, brought far

away into this wilderness by these wise, good men,

for the benighted heathen, then turned as if afraid

to stay, and retraced their steps.

I hated these men, so manifestly unfit for anything

like a Christian act—despised them, not their

books or their professed work. When I had swept

my eyes around on the space below and photographed

the world for myself, I turned and saw

these tract-leaves fluttering at my feet, in the wind,

in the snow, like the wings of a wounded bird. A

strange, fierce fit of inspiration possessed me then. I

drew my bowie-knife, drove it through the open,

fluttering leaves, and pinned them to the snow, then

turned to descend the mountain, with a chuckle of

delight.

These wild people of the forest about the base of

Mount Shasta, by their valour, their savage defiance

of the white man, and many commendable traits,

make good their claim to be called the first of the

land. They are much nobler, physically, than any

other tribes of Indians found between the Nez-Perces

of the north and the Apaches of the south. They

raise no grain, rarely dig roots, but subsist chiefly on

meat, acorn bread, nuts and fish.

These Indians have a great thirst for knowledge,

particularly of the location and extent of countries.

They are great travellers. The fact is, all Indians

are great travellers. In any tribe, even in the deserts

of Arizona, or the tribes of the plains, you will find

guides who can lead you directly to the sea to the

west, or the Sierras to the east. A traveller with

them is always a guest. He repays the hospitality

he receives by relating his travels and telling of the

various tribes he has visited, their extent, location,

and strength. No matter if the traveller is from a

hostile tribe, he is treated well and allowed to pass

through any part of the country, and go and come

when he likes. Having no fortresses, and being

constantly on the move, makes it perfectly safe for

them to let their camps and locations be known to all.

A story-teller is held in great repute; but he is

not permitted to lie or romance under any circumstances.

All he says must bear the stamp of truth,

or he is disgraced forever. Telling stories, their

history, traditions, travels, and giving and receiving

lessons in geography, are their chief diversion

around their camp and wigwam fires at night;

except the popular and never-exhausted subject of

their wars with the white man, and the wrongs of

their race.

Geography is taught by making maps in the sand

or ashes with a stick. For example, the sea a hundred

there, and rivers are led into the sea by little

crooked marks in the sand. Then sand or ashes are

heaped or thrown in ridges to show the ranges of

mountains.

This tribe is defined as having possessions of such

and such an extent on the sea. Another tribe

reaches up this river so far to the east of that tribe,

and so on, till a thousand miles of the coast are

mapped out with tolerable accuracy. In these exercises

each traveller, or any one who by his age,

observation, or learning, is supposed to know, is

expected to contribute his stock of information, and

aid in drawing the chart correctly. I have seen the

great Willamette valley, hundreds of miles away,

which they call Pooakan Charook, very well drawn,

and the location of Mount Hood pointed out with

precision. They also chart out the great Sacramento

valley, which they call Noorkan Charook,

or South Valley. This valley, however, although

a hundred miles away, is almost in sight. They

trace the Sacramento River correctly, with its

crooks and deviations, to the sea.

Their code of morals, which consists chiefly of a

contempt of death, a certainty of life after death,

temperance in all things, and sincerity, is taught by

old men too old for war; and these lessons are given

seldom, generally after some death or disaster, when

listen to tales or take part in any exercises around

the camp. The women never attempt to teach anything,

or even to correct the children. In fact, the

children are rarely corrected. To tell the truth,

they are not at all vicious. I recall no rudeness

on their part, or disrespect for their parents or

travellers. They were fortyfold more civil than

are the children of the whites.

Quite likely this is because they have not so

many temptations to do wrong as white children

have. They have a natural outlet for all their energies;

they can hunt, fish, trap, dive and swim,

run in the woods, ride, shoot, throw the lance, do

anything they like in like directions, and only receive

praise for their achievements.

There is a story published that these Indians will

not ascend Mount Shasta for fear of the Great

Spirit there. This is only partly true. They will

not ascend the mountain above the timber line

under any circumstances; but it is not fear of either

good or evil spirit that restrains them. It is their

profound veneration for the Good Spirit: the Great

Spirit who dwells in this mountain with his people as

in a tent.

This mountain, as I said before, they hold is his

wigwam, and the opening at the top whence the

smoke and steam escapes is the smoke-place of his

mistake, which I wish to correct, is the statement

of one writer, that they claim the grizzly bear

as a fallen brother, and for this reason refuse to kill

or molest him. This is far from the truth. Instead

of the grizzly bear being a bad Indian undergoing a

sort of purgatory for his sins, he is held to be a propagator

of their race.

The Indian account of their creation is briefly

this. They say that one late and severe spring-time

many thousand snows ago, there was a great storm

about the summit of Shasta, and that the great Spirit

sent his youngest and fairest daughter, of whom he

was very fond, up to the hole in the top, bidding her

speak to the storm that came up from the sea, and

tell it to be more gentle or it would blow the mountain

over. He bade her do this hastily, and not

put her head out, lest the wind would catch her in

the hair and blow her away. He told her she should

only thrust out her long red arm and make a sing,

and then speak to the storm without.

The child hastened to the top, and did as she was

bid, and was about to return, but having never yet

seen the ocean, where the wind was born and made

his home, when it was white with the storm, she

stopped, turned, and put her head out to look that

way, when lo! the storm caught in her long red hair,

and blew her out and away down and down the

the hard, smooth ice and snow, and so slid on and on

down to the dark belt of firs below the snow rim.

Now, the grizzly bears possessed all the wood and

all the land even down to the sea at that time, and

were very numerous and very powerful. They were

not exactly beasts then, although they were covered

with hair, lived in caves, and had sharp claws; but

they walked on two legs, and talked, and used clubs

to fight with, instead of their teeth and claws as they

do now.

At this time, there was a family of grizzlies

living close up to the snow. The mother had lately

brought forth, and the father was out in quest of

food for the young, when, as he returned with his

club on his shoulder and a young elk in his left hand,

he saw this little child, red like fire, hid under a fir-bush,

with her long hair trailing in the snow, and

shivering with fright and cold. Not knowing what

to make of her, he took her to the old mother, who

was very learned in all things, and asked her what

this fair and frail thing was that he had found shivering

under a fir-bush in the snow. The old mother

Grizzly, who had things pretty much her own way,

bade him leave the child with her, but never mention

it to any one, and she would share her breast

with her, and bring her up with the other children,

and maybe some great good would come of it.

The old mother reared her as she promised to do,

and the old hairy father went out every day with his

club on his shoulder to get food for his family till

they were all grown up, and able to do for themselves.

“Now,” said the old mother Grizzly to the old

father Grizzly, as he stood his club by the door and

sat down one day, “our oldest son is quite grown

up, and must have a wife. Now, who shall it be but

the little red creature you found in the snow under

the black fir-bush.” So the old grizzly father kissed

her, said she was very wise, then took up his club

on his shoulder, and went out and killed some meat

for the marriage feast.

They married, and were very happy, and many

children were born to them. But, being part of

the Great Spirit and part of the grizzly bear, these

children did not exactly resemble either of their

parents, but partook somewhat of the nature and

likeness of both. Thus was the red man created; for

these children were the first Indians.

All the other grizzlies throughout the black

forests, even down to the sea, were very proud and

very kind, and met together, and, with their united

strength, built for the lovely little red princess a

wigwam close to that of her father, the Great Spirit.

This is what is now called “Little Mount Shasta.”

After many years, the old mother Grizzly felt

done wrong in detaining the child of the Great Spirit,

she could not rest till she had seen him and restored

him his long-lost treasure, and asked his forgiveness.

With this object in view, she gathered together all

the grizzlies at the new and magnificent lodge built

for the Princess and her children, and then sent her

eldest grandson to the summit of Mount Shasta, in

a cloud, to speak to the Great Spirit and tell him

where he could find his long-lost daughter.

When the Great Spirit heard this he was so glad

that he ran down the mountain-side on the south so

fast and strong that the snow was melted off in

places, and the tokens of his steps remain to this

day. The grizzlies went out to meet him by

thousands; and as he approached they stood apart

in two great lines, with their clubs under their arms,

and so opened a lane by which he passed in great

state to the lodge where his daughter sat with her

children.

But when he saw the children, and learned how

the grizzlies that he had created had betrayed

him into the creation of a new race, he was very

wroth, and frowned on the old mother Grizzly till

she died on the spot. At this the grizzlies all set

up a dreadful howl; but he took his daughter on

his shoulder, and turning to all the grizzlies, bade

and knees, and so remain till he returned. They

did as they were bid, and he closed the door of the

lodge after him, drove all the children out into the

world, passed out and up the mountain, and never

returned to the timber any more.

So the grizzlies could not rise up any more, or

use their clubs, but have ever since had to go on all-fours,

much like other beasts, except when they have to

fight for their lives, when the Great Spirit permits them

to stand up and fight with their fists like men.

That is why the Indians about Mount Shasta will

never kill or interfere in any way with a grizzly.

Whenever one of their number is killed by one of

these kings of the forest, he is burned on the spot,

and all who pass that way for years cast a stone

on the place till a great pile is thrown up.

Fortunately, however, grizzlies are not plentiful

about the mountain.

In proof of the truth of the story that the grizzly

once walked and stood erect, and was much like a

man, they show that he has scarcely any tail, and

that his arms are a great deal shorter than his

legs, and that they are more like a man than any

other animal.

These Indians burn their dead. I have looked into

this, and, for my part, I should at the last like to be

disposed of as a savage.

There is no such thing as absolute independence.

You must ask for bread when you come into the

world, and will ask for water when about to leave it.

Freedom of body is equally a myth, and a demagogue's

text; though freedom of mind is a certainty,

and within the reach of all, grand duke or galley-slave,

peasant or prince.

Since we are always more or less dependent, a wise

and just man will seek to make the load as light as

possible on his fellows. Socrates disliked to trouble

even so humble and coarse a person as his jailer.

Mahomet mended his own clothes, and Confucius

waited on himself till too feeble to lift a hand.

If these wise men were careful not to take the time

of others to themselves, when living and capable of

doing or saying something for the good of their fellows

in return, how much more careful we should be

not to do so when dead—when we can help nothing

whatever, and nothing whatever can help or

harm us!

Holding this, I earnestly desire that my body

shall be burned, as soon as the breath has left

it, in the sheets in which I die, without any delay,

ceremony, or preparation, beyond the building of

a fire. There shall be no tomb or inscription of

any kind. If a man does any great good, history

will take note of it. If he has true friends, he will

live in their hearts while they live, and that is

churchyard, or elsewhere.

The waste of toil and money, which means

time, taken from the poor and needy by the strong

and wealthy, in conducting funerals and celebrating

doubtful virtues by building monuments, is something

enormous. Even good taste, to say nothing

of this great sacrifice of time, should rise above a

desire to ride to the grave in a hundred empty

carriages, and crop up through the grass in shameless

boast of all the virtues possible, chiselled

there. Particularly in an age when successful soap-boilers,

or packers of pork, rival the most refined

in the elegance of tombs and flourish of epitaphs.

Another good reason why I protest against this

display about the dead, is that so much is done

about the worthless and worn-out body, that the

mind is constantly directed down into the dismal

grave, instead of being lifted to the light of heaven

with the immortal spirit. One good reason is enough

for anything.

Besides, there is a waste of land in the present

custom that is inexcusable. Remember, all waste

time, all waste labour, all waste land, is loss. That

loss must be borne by some one, some portion of the

country; and it is not the wealthy or refined who

must bear it. True, they may directly take the

money from their purses, but indirectly all such losses

Death to the poor man is a terrible thing, made

tenfold terrible by the present custom of interment.

He sees that even in death there is a distinction

between him and his master, and that he is still

despised. The rich man goes to his marble vault,

which is to the poor a palace, in pomp and display of

carriages, attended by the dignitaries of the Church,

while he, the poor and despised, is quietly carted

away to a little corner set apart for the poor. Of

course, a strong and philosophic mind would laugh

at this, but to the poor it is a fearful contrast.

“Death is in the world,” and throws a shadow on

the poor that may, in part, be lifted when all are

interred alike—burned in one common fire.

These Indians, as I have before intimated, never

question the immortality of the soul. Their fervid

natures and vivid imaginations make the spirit world

beautiful beyond description, but it is an Indian's

picture, not a Christian's or Mahomedan's. No city set

upon a hill, no places curtained in silk and peopled

by beautiful women: woods, deep, dark, boundless,

with parks of game and running rivers; and above

and beyond all, not a white man there.

I have seen half-civilized Indians who are first-rate

disbelievers, but never one who is left to think

for himself. When an Indian tries to understand

our religion he stumbles, as he does when he tries to

understand us in other things.

The marriage ceremony of these people is not imposing.

The father gives a great feast, to which all

are invited, but the bride and bridegroom do not

partake of food. A new lodge is erected and furnished

more elegant than any other of the village,

by the women, each vieing with the other to do

the best in providing their simple articles of the

Indian household.

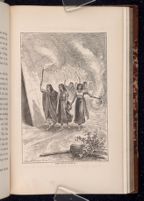

In the evening, while the feast goes on and the

father's lodge is full of guests, the women and

children come to the lodge with a great number of

pitch torches, and two women enter and take the

bride away between them: the men all the time

taking no heed of what goes on. They take her to

the lodge, chanting as they go, and making a great

flourish with their torches. Late at night the men

rise up, and the father and mother, or those standing

in their stead, take the groom between them to the

lodge, while the same flourish of torches and chant

goes on as before. They take him into the lodge

and set him on the robes by the bride. This time

the torches are not put out, but are laid one after

another in the centre of the lodge. And this is the

first fire of the new pair, which must not be allowed

to die out for some time. In fact, as a rule, in time

of peace Indians never let their lodge-fires go out so

long as they remain in one place.

When all the torches are laid down and the fire

THE INDIAN BRIDAL.

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. A young Indian woman, looking despondant, is led by a male Indian and another female Indian, both carrying burning torches. In the background are more Indians, following the procession, also carrying torches. There is a teepee off to the left. ]

ceremony is over, and the company go away in the

dark.

Late in the fall, the old chief made the marriage-feast,

and at that feast neither I not his daughter

took meat......

| CHAPTER XIX.

THE INDIANS' ACCOUNT OF THE CREATION. Unwritten history | ||