Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. | CHAPTER II.

EL VAQUERO. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER II.

EL VAQUERO. Unwritten history | ||

2. CHAPTER II.

EL VAQUERO.

DESCENDING the mountain range that

then divided California from Oregon, I fell

in with a sour, flinty-faced old man, with a

band of horses, which he was driving to the lower

settlements of California. He was short of help,

and proposed to take me into his employ for the

round trip, promising to pay me whatever my

services were worth. Glad of an opportunity to do

something at least in a new land, I scarcely thought

of the consideration, but eagerly accepted his offer,

and was enrolled as a vaquero along with a motley

set of half Indians from the north, and Mexicans

from the south.

Our duties were light, and the employment pleasant

and congenial to my nature. It was, in fact,

about the only thing I was then fit for in that strange

new country, boiling and surging with hosts of strong

men, rushing hither and thither in search of gold.

Our work consisted in keeping the saddle eight or

camping under the trees, and now and then keeping

alternate watch over the stock by night.

We were miserably fed, and half frozen while in

the mountains, but we soon descended into the quiet

Sacramento valley, where the nights are warm with

perpetual summer.

The old drover, whose great vice was avarice,

quarrelled with his men at Los Angelos, whither he

had gone to get a herd of Mexican horses after disposing

of the American stock, to take with him on

the back trip, and only escaped by adroitly suing

out warrants, and leaving them all there in

goal for threatening his life. The cause of the

trouble was the old man's avarice. He had made a

loose contract with the roving vaqueros, and on

settlement refused to pay them scarcely a tithe of

their earnings. I remained with him. We returned

to the north with a great herd of half-wild horses,

driven by a band of almost perfectly wild men: men

of all nationalities and conditions, though chiefly

Mexicans, all anxious to reach the rich mines of the

north.

Drovers in this country always leave the line of

travel and all frequented roads that they may obtain

fresh grass for their stock. In the long, long journey

north we passed through many tribes of Indians, and

except in the mountains, I noticed that all the

low, shiftless, indolent, and cowardly. The moment

we touched the mountains we seemed to touch a new

current of blood.

The old man left his motley army of vaqueros

mostly to me, and I was practically captain of the

caravan. Not unfrequently, of a morning, we would

find ourselves short of a Mexican, who had disappeared

in the night with one of the best horses. Sometimes

in the daytime these men would get sulky and

cross with the cold and cruel old master, and ride off

before his face. These men would have to be replaced

by others, picked up here and there, of a still

more questionable character.

We reached Northern California after a long and

lonely journey, through wild and fertile valleys, with

only the smoke of wigwams curling from the fringe

of trees that hemmed them in, or from the river bank

that cleft the little Edens to disprove the fancy that

here might have been the Paradise and here the scene

of the expulsion.

We crossed flashing rivers, still white and clear,

that since have become turbid yellow pools with

barren banks of boulders, shorn of their overhanging

foliage, and drained of flood by ditches that the

resolute miner has led even around the mountain

tops.

On entering Pit River Valley we met with thousands

fishing, perhaps, but they kindly assisted us across

the two branches of the river, and gave no signs of

ill-will

We pushed far up the valley in the direction of

Yreka, and there pitched camp, for the old man

wished to recruit his horses on the rich meadows of

wild grass before driving them to town for market.

We camped against a high spur of a long timbered

hill, that terminated abruptly at the edge of the valley.

A clear stream of water full of trout, with willow-lined

banks, wound through the length of the

narrow valley, entirely hidden in the long grass and

leaning willows.

The Pit River Indians did not visit us here, neither

did the Modocs, and we began to hope we were entirely

hidden, in the deep narrow little valley, from

all Indians, both friendly and unfriendly, until one

evening some young men, calling themselves Shastas,

came into the camp. They were very friendly, however,

were splendid horsemen, and assisted to bring

in and corral the horses like old vaqueros.

Our force was very small, in fact we had then

less than half-a-dozen men; and the old man, for a day

or two, employed two of these young fellows to attend

and keep watch about the horses. One morning

three of our vaqueros mounted and rode off, cursing

my sour old master for some real or fancied wrong,

beside myself, so that the two young Indians had to

be retained.

Some weeks wore on pleasantly enough, when we

began to prepare to strike camp for Yreka. Thus far

we had not seen the sign of a Modoc Indian.

It was early in the morning. The rising sun was

streaming up the valley, through the fringe of fir and

cedar trees. The Indian boys and I had just returned

from driving the herd of horses a little way down

the stream. The old man and his companion were

sitting at breakfast, with their backs to the high bare

wall with its crown of trees. The Indians were

taking our saddle-horses across the little stream to

tether them there on fresh grass, and I was walking

idly towards the camp, only waiting for my tawny

young companions. Crack! crash! thud!!

The two men fell on their faces and never uttered

a word. Indians were running down the little lava

mountain side, with bows and rifles in their hands,

and the hanging, rugged brow of the hill was curling

in smoke. The Ben Wright tragedy was bearing its

fruits.

I started to run, and ran with all my might towards

where I had left the Indian boys. I remember distinctly

thinking how cowardly it was to run and desert

the wounded men, with the Indians upon them,

and I also remember thinking that when I got to the

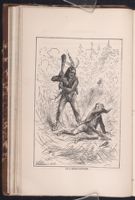

AT A DISADVANTAGE

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. An Indian towers over a caucasian, brandishing a club. The white man cowers on the ground, and has dropped his gun. In the background are pine trees and a horse.]

laid hold of the pistol in my belt, and could have

fired, and should have done so, but I was thoroughly

frightened, and no doubt if I had succeeded in reaching

the willows I would have thought it best to go

still further before turning about.

How rapidly one thinks at such a time, and how

distinctly one remembers every thought.

All this, however, was but a flash, the least part of

an instant. Some mounted Indians that had been

stationed up the valley darted out at the first shot,

and one of them was upon me before I saw him, for

I was only concerned with the Indians pouring down

the little hill out of the smoke into the camp.

I was struck down by a club, or some hard heavy

object, maybe the pole of a hatchet, possibly only a

horse's hoof, as he plunged in the air.

When I recovered, which must have been some

minutes after, an Indian was rolling me over and

pulling at the red Mexican sash around my waist.

He was a powerful savage, painted red, half-naked,

and held a war-club in his hand. I clutched tight

around one of his naked legs with both my arms.

He tried to shake me off, but I only clutched the

tighter. I looked up, and his terrible face almost

froze my blood. I relaxed my hold from want of

strength. I shut my eyes, expecting the war-club

to crash through my brain and end the matter at

allows himself to laugh, and winding the red sash

around him strode down the valley.

My pistol was gone. I crept through the grass

into the stream, then down the stream to where it

nearly touched the forest, and climbed over and slipped

into the wood.

From the timber rim I looked back, but could see

nothing whatever. The band of horses was gone,

the Indians had disappeared. All was still. It was

truly the stillness of death.

The Indian boys, my companions, had escaped with

the ponies into the wood, and I stole up the edge of

the forest till I struck their trail, and following on a

little way, weak and bewildered, I met them stealing

back on foot to my assistance.

My mind and energy both now seemed to give way.

We reached the Indian camp somehow, but I have

but a vague and shadowy recollection of what passed

during the next few weeks. For the most part, as

far as I remember, I sat by the lodges or under the

trees, or rode a little, but never summoned spirit or

energy to return to the fatal camp.

I asked the Indians to go down and see what had

become of the two bodies, but they would not think

of it. This was quite natural, since they will not

revisit their own camp after being driven from it by

an enemy, until it is first visited by their priest or

appeases the angered spirit that has brought the

calamity upon them. The Indian camp was a

small one, and made up mostly of women and children.

It was in a vine-maple thicket, on the bend of

a small stream called by the Indians Ki-yi-mem, or

white water. By the whites I think it is now called

Milk Creek. A singular stream it is; sometimes it

flows very full, and then is nearly dry; sometimes it

is almost white with ashes and fine sand, and then it

is perfectly clear with a beautiful white sand border

and bottom. The Indians say, that it is also sometimes

so hot as to burn the hand, and then again is as

cold as the McCloud; but this last phenomenon I

never witnessed. The changes, however, whatever

they are, are caused by some internal volcanic action

of Mount Shasta, from which the stream flows in

great springs.

The camp was but a temporary one, and pitched

here for the purpose of gathering and drying a sort

of mountain camas root from the low marshy springs of

this region. This camas is a bulbus root shaped much

like an onion, and is prepared for food by roasting in

the ground, and is very nutritious. Sometimes it is

kneaded into cakes and dried. In this state if kept

dry it will retain its sweetness and fine properties for

months.

I could not have been treated more kindly even at

suited to restore a shattered nervous system and organization

so delicate as my own, and I got on slowly.

Perhaps after all I only needed rest, and it is quite

likely the Indians saw this, for rest I certainly had,

such as I never had before or since. It was as near

a life of nothingness down there in the deep forest as

one well could imagine. There were no birds in the

thicket about the camp, and you even had to go out

and climb a little hill to get the sun.

This hill sloped off to the south with the woods

open like a park, and here the children and some

young women sported noiselessly or basked in the

sun.

If there is any place outside of the tomb that can

be stiller than an Indian camp when stillness is required,

I do not know where it is. Here was a camp

made up mostly of children, and what is usually called

the most garrulous half of mankind, and yet all was

so still that the deer often walked stately and unconscious

into our midst.

No mention was made of my going away or remaining.

I was permitted as far as the Indians were

concerned to forget my existence, and so I dreamed

along for a month or two and began to get strong

and active in mind and body.

I had dreamed a long dream, and now began to

waken and think of active life. I began to hunt

delights and their sorrows.

Did the world ever stop to consider how an Indian

who has no theatre, no saloon, no whisky shop, no

parties, no newspaper, not one of all our hundreds

of ways and means of amusement, spends his evening?

Think of this! He is a human being, full of passion

and of poetry. His soul must find some expression;

his heart some utterance. The long, long nights of

darkness, without any lighted city to walk about in,

or books to read. Think of that! Well, all this

mind, or thought, or soul, or whatever it may be,

which we scatter in so many directions, and on so

many things, they centre on one or two.

What if I told you that they talk more of the

future and know more of the unknown than the

Christian? That would shock you. Truth is a

great galvanic battery.

No wonder they die so bravely, and care so little

for this life, when they are so certain of the next.

After a time we moved camp to a less dangerous

quarter, and out into the open wood. I now took

rides daily or hunted bear or deer with the Indians.

Yet all this time I had a sort of regretful idea that

I must return to the white people and give some

account of what had happened. Then I reflected

how inglorious a part I had borne, how long I had

remained with the Indians, though for no fault of

on the subject.

In this new camp I seemed to come fully to my

strength. I took in the situation and the scenery

and began to observe, to think, and reflect.

Here, for the first time, I found myself alone in

an Indian camp without any obligation or anything

whatever binding me or calling me back to the

Saxon. I began to look on the romantic side of my

life, and was not displeased. I put aside the little

trouble of the old camp and became as careless as a

child.

The wood seemed very very beautiful. The air

was so rich, so soft and pure in the Indian summer,

that it almost seemed that you could feed upon it.

The antlered deer, fat, and tame almost as if fed

in parks, stalked by, and game of all kinds filled

the woods in herds. We hunted, rode, fished and

rested beside the rivers.

What a fragrance from the long and bent fir boughs.

What a healthy breath of pine! All the long sweet

moonlight nights the magnificent forest, warm and

mellow-like from sunshine gone away, gave out

odours like burnt incense from censers swinging in

some mighty cathedral.

If I were to look back over the chart of my life for

happiness, I should locate it here if anywhere. It is

true that there was a little cast of concern in all this

and my life, I think, partook of the Indian's melancholy,

which comes of solitude and too much thought,

but the memory of these few weeks always appeals

to my heart, and strikes me with a peculiar gentleness

and uncommon delight.

The Indians were not at war with the whites, nor

were they particularly at peace. In fact, they assert

that there has never been any peace since they or

their fathers can remember. The various tribes,

sometimes at war, were also then at peace, so that

nothing whatever occurred to break the calm repose

of the golden autumn.

The mountain streams went foaming down among

the boulders between the leaning walls of yew and

cedar trees toward the Sacramento. The partridge

whistled and called his flock together when the sun

went down; the brown pheasants rustled as they ran

in strings through the long brown grass, but nothing

else was heard. The Indians, always silent, are unusually

so in autumn. The majestic march of the season

seems to make them still. They moved like

shadows. The conflicts of civilization were beneath

us. No sound of strife; the struggle for the

possession of usurped lands was far away, and I

was glad, glad as I shall never be again. I know I

should weary you, to linger here and detail the life

we led; but as for myself I shall never cease to relive

elsewhere.

With nothing whatever to do but learn their

language and their manners, I made fast progress,

and without any particular purpose at first, I soon

found myself in possession of that which, in the

hands of a man of culture would be of great

value. I saw then how little we know of the

Indian. I had read some flaming picture books of

Indian life, and I had mixed all my life more or less

with the Indians, that is, such as are willing to mix

with us on the border, but the real Indian, the

brave, simple, silent and thoughtful Indian who

retreats from the white man when he can, and fights

when he must, I had never before seen or read a

line about. I had never even heard of him. Few

have. Perhaps ten years from now the red man, as

I found him there in the forests of his fathers, shall

not be found anywhere on earth. I am now certain

that if I had been a man, or even a clever wide-awake

boy, with any particular business with the Indians, I

might have spent years in the mountains, and known

no more of these people than others know. But lost

as I was, and a dreamer, too ignorant of danger to

fear, they sympathized with me, took me into their inner

life, told me their traditions, and sometimes showed

me the “Indian question” from an Indian point of

view.

After mingling with these people for some months,

I began to say to myself, Why cannot they be permitted

to remain here? Let this region be untraversed

and untouched by the Saxon. Let this be a

great national park peopled by the Indian only. I

saw the justice of this, but did not at that time conceive

the possibility of it.

No man leaps full-grown into the world. No

great plan bursts into full and complete magnificence

and at once upon the mind. Nor does any one suddenly

become this thing or that. A combination of

circumstances, a long chain of reverses that refuses to

be broken, carries men far down in the scale of life,

without any fault whatever of theirs. A similar but

less frequent chain of good fortune lifts others up

into the full light of the sun. Circumstances which

few see, and fewer still understand, fashion the destinies

of nearly all the active men of the plastic west.

The world watching the gladiators from its high seat

in the circus will never reverse its thumbs against the

successful man. Therefore, succeed, and have the approval

of the world. Nay! what is far better, deserve

to succeed, and have the approval of your own conscience.

| CHAPTER II.

EL VAQUERO. Unwritten history | ||