Unwritten history life amongst the Modocs |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. | CHAPTER VIII.

BLOOD ON THE SNOW. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| CHAPTER VIII.

BLOOD ON THE SNOW. Unwritten history | ||

8. CHAPTER VIII.

BLOOD ON THE SNOW.

THERE was a tribe of Indians camped down

on the rapid, rocky Klamat river — a sullen,

ugly set were they, too: at least so said The

Forks. Never social, hardly seeming to notice the

whites, who were now thick about them, below them,

above them, on the river and all around them. Sometimes

we would meet one on the narrow trail; he

would gather his skins about him, hide his bow and

arrows under their folds, and, without seeming to see

any one, would move past us still as a shadow. I do

not remember that I ever saw one of these Indians

laugh, not even to smile. A hard-featured, half-starved

set of savages, of whom the wise men of the

camp prophesied no good.

The snow, unusually deep this winter, had driven

them all down from the mountains, and they were

compelled to camp on the river.

The game, too, had been driven down along with

the Indians, but it was of but little use to them.

rifles of the whites in the killing of the game. The

whites fairly filled the cabins with deer and elk, got all

the lion's share, and left the Indians almost destitute.

Another thing that made it rather more hard on

the Indians than anything else, was the utter failure

of the annual run of salmon the summer before, on

account of the muddy water. The Klamat, which

had poured from the mountain lakes to the sea as

clear as glass, was now made muddy and turbid from

the miners washing for gold on its banks and its

tributaries. The trout turned on their sides and

died; the salmon from the sea came in but rarely on

account of this; and what few did come were pretty

safe from the spears of the Indians, because of the

coloured water; so that supply, which was more than

all others their bread and their meat, was entirely

cut off.

Mine? It was all a mystery to these Indians as

long as they were permitted to live. Besides, there

were some whites mining who made poor headway

against hunger. I have seen them gather in groups

on the bank above the mines and watch in silence for

hours as if endeavouring to make it out; at last they

would shrug their shoulders, draw their skins closer

about them, and stalk away no wiser than before.

Why we should tear up the earth, toil like gnomes

from sun-up to sun-down, rain or sun, destroy the

a mystery—it was a terror. I believe they accepted

it as a curse, the work of evil spirits, and so bowed to

it in sublime silence.

This loss of salmon was a greater loss than you

would suppose. These fish in the spring-time pour

up these streams from the sea in incalculable swarms.

They fairly darken the water. On the head of the

Sacramento, before that once beautiful river was

changed from a silver sheet to a dirty yellow stream,

I have seen between the Devil's Castle and Mount

Shasta the stream so filled with salmon that it was

impossible to force a horse across the current. Of

course, this was not usual, and now can only be met

with hard up at the heads of mountain streams where

mining is not carried on, and where the advance of

the fish is checked by falls on the head of the stream.

The amount of salmon which the Indians would

spear and dry in the sun, and hoard away for winter,

under such circumstances, can be imagined; and I

can now better understand their utter discomfiture at

the loss of their fisheries than I did then.

A sharp, fierce winter was upon them; for reasons

above stated they had no store of provisions on hand,

save, perhaps, a few dried roots and berries; and the

whites had swept away and swallowed up the game

before them as fast as it had been driven by the

winter from the mountains. Yet I do not know that

and I do not remember hearing any allusion made to

these things by the bearded men of the camp, old

enough, and wise enough too, to look at the heart of

things. Perhaps it was because they were all so busy

and intent on getting gold. I do remember distinctly,

however, that there was a pretty general feeling

against the Indians down on the river—a general

feeling of dislike and distrust.

What made matters worse, there was a set of men,

low men, loafers, and of the lowest type, who would

hang around those lodges at night, give the Indians

whiskey of the vilest sort, debauch their women, and

cheat the men out of their skins and bows and arrows.

There was not a saloon, not a gambling den in camp

that did not have a sheaf of feathered, flint-headed

arrows in an otter quiver, and a yew bow hanging

behind the bar.

Perhaps there was a grim sort of philosophy in the

red man so disposing of his bow and arrows now that

the game was gone and they were of no further use.

Sold them for bread for his starving babes, maybe.

How many tragedies are hidden here? How many

tales of devotion, self-denial, and sacrifice, as true as

the white man ever lived, as pure, and brave, and

beautiful as ever gave tongue to eloquence or pen to

song, sleep here with the dust of these sad and silent

people on the bank of the stormy river!

In this condition of things, about mid-winter, when

the snow was deep and crusted stiff, and all nature

seemed dead and buried in a ruffled shroud, there was

a murder. The Indians had broken out! The prophesied

massacre had begun! Killed by the Indians!

It swept like a telegram through the camp. Confused

and incoherent, it is true, but it gathered force

and form as the tale flew on from tongue to tongue,

until it assumed a frightful shape.

A man had been killed by the Indians down at the

rancheria. Not much of a man, it is true. A “capper;”

a sort of tool and hanger-on about the lowest gambling

dens. Killed, too, down in the Indian camp

when he should have been in bed, or at home, or at

least in company with his kind.

All this made the miners hesitate a bit as they

hurriedly gathered in at The Forks, with their long

Kentucky rifles, their pistols capped and primed, and

bowie knives in their belts.

But as the gathering storm that was to sweep the

Indians from the earth took shape and form, these

honest men stood out in little knots, leaning on their

rifles in the streets, and gravely questioned whether,

all things considered, the death of the “Chicken,” for

that was the dead man's name, was sufficient cause

for interference.

To their eternal credit these men mainly decided

that it was not, and two by two they turned away,

rack, and turned their thoughts to their own affairs.

But the hangers-on about the town were terribly

enraged. “A man has been killed!” they proclaimed

aloud. “A man has been murdered by the

savages!! We shall all be massacred! butchered!

burnt!!”

In one of the saloons where men were wont to

meet at night, have stag-dances, and drink lightning,

a short, important man, with the print of a glass-tumbler

cut above his eye, arose and made a speech.

“Fellow-miners (he had never touched a pick in

his life), I am ready to die for me country! (He

was an Irishman sent out to Sydney at the Crown's

expense.) What have I to live for? (Nothing

whatever, as far as anyone could tell.) Fellow-miners,

a man has been kilt by the treacherous

savages—kilt in cold blood! Fellow-miners, let us

advance upon the inemy. Let us—let us—fellow-miners,

let us take a drink and advance upon the

inemy.”

This man had borrowed a pistol, and held or flourished

it in his hand as he talked to the crowd of

idlers, rum-dealers, and desperadoes—to the most of

whom any diversion from the monotony of camp-life,

or excitement, seemed a blessing.

“Range around me. Rally to the bar and take a

drink, every man of you, at me own ixpense.” The

a man not much above the type of the speaker,

ventured a mild remonstrance at this wholesale

generosity; but the pistol, flourished in a very suggestive

way, settled the matter, and, with something

of a groan, he set his decanters to the crowd, and

became a bankrupt.

This was the beginning; they passed from saloon

to saloon, or, rather, from door to door; the short,

stout Irishman making speeches and the mob

gathering force and arms as it went, and then, wild

with drink and excitement, moved down upon the

Indians, some miles away on the bank of the river.

“Come,” said the Prince to me, as they passed out

of town, “let us see this through. Here will be

blood. We will see from the hill overlooking the

camp. I hope the Indians are `on it'—hope to God

they are `heeled,' and that they will receive the

wretches warmly as they deserve.” The Prince was

wild.

Maybe his own wretchedness had something to do

with his wrath; but I think not. I should rather say

that had he been in strength and spirits, and had his

pistols, which had long since been disposed of for

bread, he had met this mob face to face, and sent

it back to town or to the place where the wretches

belonged.

We followed not far behind the crowd of fifty or

hatchets.

The trail led to a little point overlooking the bar

on which the Indian huts were huddled.

The river made a bend about there. It ground

and boiled in a crescent blocked with running

ice and snow. They were out in the extreme curve

of a horse-shoe made by the river, and we advanced

from without. They were in a net. They had only

a choice of deaths; by drowning, or death at

the hands of their hereditary foe.

It was nearly night; cold and sharp the wind blew

up the river and the snow flew around like feathers.

Not an Indian to be seen. The thin blue smoke

came slowly up, as if afraid to leave the wigwams,

and the traditional, ever watchful and wakeful

Indian dog was not to be seen or heard. The men

hurried down upon the camp, spreading out upon

the horse-shoe as they advanced in a run.

“Stop here,” said the Prince; and we stood from

the wind behind a boulder that stood, tall as a cabin,

upon the bar. The crowd advanced to within half a

pistol shot, and gave a shout as they drew and

levelled their arms. Old squaws came out—bang!

bang! bang! shot after shot, and they were pierced

and fell, or turned to run.

Some men sprung up, wounded, but fell the

instant, for the whites, yelling, howling, screaming,

length man, woman, or child. Some attempted the

river, I should say, for I afterwards saw streams of

blood upon the ice, but not one escaped; nor was a

hand raised in defence. It was all done in a little time.

Instantly as the shots and shouts began we two

advanced, we rushed into the camp, and when we

reached the spot only now and then a shot was

heard within a lodge, dispatching a wounded man or

woman. The few surviving children—for nearly all

had been starved to death—had taken refuge under

skins and under lodges overthrown, hidden away as

little kittens will hide just old enough to spit and

hiss, and hide when they first see the face of man.

These were now dragged forth and shot. Not all

these men who made this mob, bad as they were,

did this—only a few; but enough to leave, as far

as they could, no living thing. Christ! it was

pitiful! The babies did not scream. Not a wail,

not a sound. The murdered men and women, in

the few minutes that the breath took leave, did not

even groan.

As we came up a man named “Shon”—at least,

that was all the name I knew for him—held up a

baby by the leg, a naked, bony little thing, which he

had dragged from under a lodge—held it up with one

hand, and with the other blew its head to pieces with

his pistol.

I must stop here to say that this man Shon soon

left camp, and was afterwards hung by the Vigilance

Committee near Lewiston, Idaho Territory; that he

whined for his life like a puppy, and died like

a coward as he was. I chronicle this fact with a

feeling of perfect delight.

He was a tall, spare man, with small, grey eyes,

a weak, wicked mouth, colourless and treacherous,

that was for ever smiling and smirking in your face.

Shun a man like that. A man who always smiles

is a treacherous-natured, contemptible coward.

He knows, himself, how villainous and contemptible

he is, and he feels that you know it too, and so

tries to smile his way into your favour. Turn away

from the man who smiles and smiles, and rubs his

hands as if he felt and all men knew, that they were

really dirty.

You can put more souls of such men as that inside

of a single grain of sand than there are dimes in the

national debt.

This man threw down the body of the child among

the dead, and rushed across to where a pair of ruffians

had dragged up another, a little girl, naked, bony,

thin as a shadow, starved into a ghost. He caught

her by the hair with a howl of delight, placed the

pistol to her head and turned around to point the

muzzle out of range of his companions who stood

around on the other side.

The child did not cry—she did not even flinch.

Perhaps she did not know what it meant; but I

should rather believe she had seen so much of death

there, so much misery, the steady, silent work of the

monster famine through the village day after day,

that she did not care. I saw her face; it did not

even wince. Her lips were thin and fixed, and firm

as iron.

The villian, having turned her around, now lifted

his arm, cocked the pistol, and—

“Stop that, you infernal scoundrel! Stop that,

or die! You damned assassin, let go that child, or

I will pitch you neck and crop into the Klamat.”

The Prince had him by the throat with one hand,

and with the other he wrested the pistol from his

grasp and threw it into the river. The Prince had

not even so much as a knife. The man did not know

this, nor did the Prince care, or he had not thrown

away the weapon he wrung from his hand. The

Prince pushed the child behind him, and advanced

towards the short, fat Sydney convict, who had now

turned, pistol in hand, in his direction.

“Keep your distance, you Sydney duck, keep your

distance, or I will send you to hell across lots in a

second.”

There are some hard names given on the Pacific;

but when you call a man a “Sydney duck” it is

well understood that you mean blood. If you call a

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE STORY.

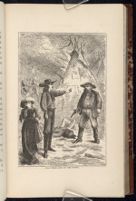

[Description: 645EAF. Illustration page. Two men stand facing each other. One is pointing at the other and one has a gun in his right hand, pointed downwards. There are two dead men behind the man with the gun, and in the background there is another man with a gun pointed at an Indian. There are three teepees in the background, and a man and child are standing huddled together looking at the two men. ]

down on the spot, or he will perform that office for

you. If he does not, or does not attempt it, he is

counted a coward and is in disgrace.

When you call a man a “Sydney duck,” however,

something more than blows are meant; that means

blood. There is but one expression, a vile one, that

cannot well be named, that means so much, or carries

so much disgrace as this.

The man turned away cowed and baffled. He had

looked in the Prince's face, and saw that he was born

his master.

As for myself, I was not only helpless, but, as was

always the case on similar occasions, stupid, awkward,

speechless. I went up to the little girl, however,

got a robe out of one of the lodges—for they had not

yet set fire to the village—and put it around her

naked little body. After that, as I moved about

among the dead, or stepped aside to the river to see

the streams of blood on the snow and ice, she followed

close as a shadow behind me, but said nothing.

Suddenly there was a sharp yell, a volley of oaths,

exclamations, a scuffle and blows.

“Scalp him! Scalp him! the little savage! Scalp

him and throw him in the river!”

From out of the piles of dead somewhere, no one

could tell exactly where or when, an apparition had

sprung up—a naked little Indian boy, that might

with a knotted war-club, and fallen upon his foes like

a fury.

The poor little hero, starved into a shadow, stood

little show there, though he had been a very Hercules

in courage. He was felled almost instantly by kicks

and blows; and the very number of his enemies saved

his life, for they could neither shoot nor stab him with

safety, as they crowded and crushed around him.

How or why he was finally spared, was always

a marvel. Quite likely the example of the Prince

had moved some of the men to more humanity. As

for Shon and Sydney, they had sauntered off with

some others towards town at this time, which also,

maybe, contributed to the Indian boy's chance for

life.

When the crowd that had formed a knot about him

had broken up, and I first got sight of him, he was

sitting on a stone with his hands between his naked

legs, and blood dripping from his long hair, which

fell down in strings over his drooping forehead. He

had been stunned by a grazing shot, no doubt, and

had fallen among the first. He came up to his work,

though, like a man, when his senses returned, and

without counting the chances, lifted his two hands to

do with all his might the thing he had been taught.

Valour, such valour as that, is not a cheap or common

thing. It is rare enough to be respected even by

to despise such courage. He is moved to this altogether

by the lowest kind of jealousy. A coward

knows how entirely contemptible he is, and can

hardly bear to see another dignified with that

noble attribute which he for ever feels is no part

of his nature.

So this boy sat there on the stone as the village

burned, the smoke from burning skins, the wild-rye

straw, willow-baskets and Indian robes, ascended,

and a smell of burning bodies went up to the Indians'

God and the God of us all, and no one said nay, and

no one approached him; the men looked at him from

under their slouched hats as they moved around,

but said nothing.

I pitied him. God knows I pitied him. I clasped

my hands together in grief. I was a boy myself,

alone, helpless, in an army of strong and unsympathetic

men. I would have gone up and put my arms

about the wild and splendid little savage, bloody and

desperate as he was, so lonely now, so intimate with

death, so pitiful! if I had dared, dared the reproach

of men-brutes.

But besides that there was a sort of nobility about

him; his recklessness, his desire to die, lifting his

little arms against an army of strong and reckless

men, his proud and defiant courage, that made me

feel at once that he was above me, stronger, somehow

the only boys in the camp; and my heart went out,

strong and true, towards him.

The work of destruction was now too complete. There

was not found another living thing—nothing but two

or three Indians that had been shot and shot, and yet

seemed determined never to die, that lay in the bloody

snow down towards the rim of the river.

Naked nearly, they were, and only skeletons, with

the longest and blackest hair tangled and tossed, and

blown in strips and strings, or in clouds out on the

white and the blood-red snow, or down their tawny

backs, or over their bony breasts, about their dusky

forms, fierce and unconquered, with the bloodless lips

set close, and blue, and cold, and firm, like steel.

The dead lay around us, piled up in places, limbs

twisted with limbs in the wrestle with death; a mother

embracing her boy here; an arm thrown around a

neck there: as if these wild people could love as well

as die.

| CHAPTER VIII.

BLOOD ON THE SNOW. Unwritten history | ||