The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. | V. 7 |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 7

DEVICES FOR HEATING,

LIGHTING, VENTILATION,

AND COOKING

V.7.1

THE CENTRAL HEARTH AND THE

LOUVER

THE MEANING OF LOCUS FOCI AND TESTU

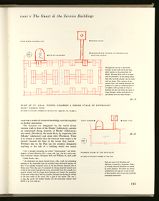

One of the striking typological characteristics of the guest

and service buildings on the Plan is the squares in the

center of these houses referred to varyingly as locus foci and

testu (fig. 358A-C). The first of these terms clearly refers

to the "fireplace" or open hearth in the middle of the floor

which heats the house. The second, testu, requires some

explanation. It has generally been taken to be an abbreviation

for the word testudo ("turtle" or "roof"),[226]

but I do

not think that this is the correct interpretation. Testu, as an

abbreviation for testudo, with no sign given to indicate that

a part of the word is missing, is not consistent with the

author's other abbreviations,[227]

and there is no reason to

assume that he departed from his normal procedure because

of the smallness of the space in which the word had

to be inscribed. The testu square in the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers (fig. 358B) is large enough to accommodate

the whole word testudo and several other words if

necessary. What the scribe had in mind, in my opinion, was

the word testu, exactly as it is written—a rare yet perfectly

meaningful term.

Testu (indeclinable) means the "lid of a pot."[228]

It is

closely related to testa, which means "shell," either the

shell that covers a testaceous animal, the human skull

(testa hominis), or human artifacts of comparable construction,

359. WIJCHEN, GELDERLAND, THE NETHERLANDS

This Iron Age house of modest design was unearthed on a chain of hills skirting

a moor that once may have formed an outer arm of the Maas. The house was

internally divided into two areas one of which contained its hearth. Four

independent posts surrounding the hearth are most reasonably explained as the

supports of a small roof protecting an opening in the main roof admitting light

and air and also allowing the smoke to escape.

NEAR THE RIVER MAAS (10KM WEST OF NIJMEGEN)

PLAN. IRON AGE HOUSE [after F. Bloemen, 1933, 5, fig. 5]

both these words. It shares with them the basic meaning

of "protective cover." In everyday language testudo meant a

"tortoise" or "turtle"; in military language it was the name

for the protective covering formed when soldiers held their

shields overhead and locked them together. By analogy, in

architectural terminology—both classical and medieval—

testudo came to be the word used for "roof," usually a roof

of timber, but also by extension, a "vaulted roof."[229]

Even supposing that the author of the Plan had in mind

testudo, rather than testu, it is unlikely that he referred to

the principal roof of the building; rather, he must have

meant a roof equal in size with the square in which

the term was written; and since this square is designated

both as testu and as locus foci, it is most probably to be understood

as "a protective shield above the hearth," the purpose

of which must have been to form a cover for a central smoke

outlet. Such openings in the roof above the hearth are, in

fact, a feature of the protohistoric and early medieval building

tradition just discussed, and they remained an intrinsic

part of vernacular buildings throughout the Middle Ages.

360. KRAGHEDE, VENDSYSSEL, DENMARK

This Danish Iron Age House is of very similar design to the Dutch specimen

shown in the preceding figure. It shows four independent inner posts related to

the hearth in an identical manner. In houses of relatively small dimensions it

made sense to support the hearth-protecting lantern by poles rising from the

ground. In larger houses, as the subsequent figures show, this was accomplished

by timbers forming part of the roof frame.

PLAN. IRON AGE HOUSE

[after Hatt, 1928, 254, fig. 25]

The scribe is very careful with his abbreviations and in general

designates contractions or omissions by the customary symbols. I

would draw attention especially to the word longitudo in one of the

explanatory titles of the Church (cf. Vol. I, p. 77); it is contracted into

LONGĪT̄·, but the fact that the letters UDO are missing is indicated by a

horizontal bar over the IT and a point beside the T·. In two other titles

of the same Church the word latitudo is spelled out. The word pedum

in the same titles is either spelled out or contracted into pedū (a horizontal

bar indicating the missing m). The Plan, it is true, contains a few

capricious abbreviations (cf. III, 12) and in some cases (I am aware

of six, (cf. III, 11) the horizontal bar, standing for m, is omitted over

a terminal vowel; but it appears to me unlikely that an entire syllable

would be dropped, either intentionally or inadvertently, from a technical

term that appears on three crucial places of the Plan, that was not used

in this sense in classical times, and must have been relatively rare even

in Medieval Latin.

For testa, testu, and testudo, see Walde and Hofmann, II, 1938, 675,

677; Forcellini, IV, 1940, 710, 714; Lewis and Short, 1945, 1862, 1864.

For the occurrence of the term in medieval literature, see the indices

in Lehmann-Brockhaus, II, 1938, 332; and Schlosser, 1896, 481. The

word-index in Lehmann-Brockhaus, 1955ff, was not yet published at

the time of this writing.

THE LIGHT AND SMOKE HOLES OF THE

NORDIC SAGA HOUSE

This roof device is well attested in the Nordic Sagas where,

according to its function, it is referred to varyingly as

"smoke hole" (reykháfr, reykberi), "light inlet" (ljóri), or

"air inlet" (vindgluggr, vindauga).[230]

Little is known about

the size and shape of these devices, but apparently they

were large enough to be used as an escape hatch when all

other passages were blocked. The Sagas abound with tales

of exits made in this manner. A passage from the Vatnsdœla

Saga gives a typical example: "And so was this [house]

arranged that from that pile of goods, one could step up

into a big smoke hole [í einn storan reykbera] which was

over the hall [er á var skálanum] and when the marauder

investigated the pile, þorsteinn was outside" [var þorsteinn

úti, the sense being: þorsteinn had gained his freedom by

escaping through the smoke hole].[231]

The openings of these light and smoke holes could be

closed by means of wooden shutters (spjaeld) or boards

(fjöl) which were placed in position with the help of a pole

361. NEW COLLEGE, OXFORD, ENGLAND

THE GREAT HALL, 1378-1386

[after Loggan, 1675]

The lantern-surmounted ridges of these buildings built approximately one hundred years apart attest the effectiveness of the device on larger

structures of monumental character.

made from the stomach lining of a hog mounted on movable

frames (skjágluggr, skjávindauga). We read of the first type

in Haralds saga harđrađa: "The king then let a board

(fjöl) be moved in front of the light hole (ljórann) so that

only a small opening was left . . . Einar entered and said,

`Dark is it in the King's Council Hall (málstofa).' At the

same moment men rushed on him. . . ."[232] The second type is

mentioned in an equally dramatic passage of the GullÞoris

saga, where Þorir, finding himself trapped in the hall

by Þorbjörn's housecarls, with all exits blocked, "grabbed

a pole and raised it under the `skin hole' (skjárinn) and

there went out and pulled up the pole, and then ran up to

the mountains."[233]

Haralds Saga Hardrada, chap. 63, ed. Gudmundsson, VI, 1831, 281.

Cf. also Heímskringla, ed. Unger, 1868, 579; and in English translation

by Monsen, 1932, 531.

PROTOHISTORIC EVIDENCE FOR

LIGHT AND SMOKE HOLES

Evidence for the existence of poles rising from the ground THE GREAT HALL, 1448-1480 [after Loggan, 1675]

to form a canopy around and over the hearth has been

found in aisled Iron Age houses at Hodorf, Germany (fig.

307), and Wijchen, Holland (fig. 359), as well as in the

362. MAGDALEN COLLEGE, OXFORD, ENGLAND

single-span Iron Age houses at Kraghede, Vendsyssel,

Denmark (fig. 360); Källberga, Alunda (Uppland), Sweden;

and the Migration Period village Vallhagar on the island

of Gotland, Sweden.[234]

363. NAPA VALLEY, CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA DAIRY BARN WITH LOUVERS

The most common and widely diffused survival form of the testu of the Plan are the

lantern-surmounted openings in the roofs of barns found at every community of the

great farm belt of Canada and the United States.

The relatively rare occurrence of these hearth poles

suggests, however, that in general the protective shields

were mounted directly on the roof rather than on special

supports. The latter system would have been entirely inappropriate

in larger halls, since it would have required an

underpinning of timbers entirely out of scale with the

superstructure that it served to support.

For Hodorf, see Haarnagel, 1937; for Wijchen, see Bloemen, 1933,

5, fig. 5; for Nauen, see Doppelfeld, 1937/38; for Kraghede and Källberga,

see Stenberger, 1933, 175 and 159; for Vallhagar, see Vallhagar,

ed. Stenberger, 1955, 220 and 223.

MEDIEVAL EXAMPLES

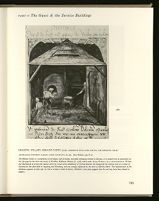

A fairly accurate picture of these smoke and air hole LOUVER ON COLLAPSING BARN

coverings may be obtained from some of the old engravings

of early English college halls, for instance, those of Oxford's

New College (fig. 361) and Magdalen College (fig. 362), as

shown in David Loggan's illustratious Oxonia Illustrata of

1675.[235]

New College Hall, the oldest of the surviving college

halls of Oxford, was built between 1378-1386 by William

of Wykeham. Magdalen College was founded in 1448 by

William of Waynflete, but its buildings were not completed

until 1480. Both these halls were built during a period when

new discoveries in the technique of roof construction made

it possible to dispense with the two rows of roof-supporting

posts which formerly divided the hall into a nave and two

364. NEAR BENICIA, CALIFORNIA

cover the space in a single span but also to lift the roof upon

walls of considerable height. Yet even in this new and more

fashionable hall, which permitted large windows, the traditional

opening in the roof above the hearth was retained

as the principal exit for smoke. The roof of the hall of

Magdalen College shows what extraordinary dimensions

these openings could obtain.

The medieval term for these smoke holes is fumerium

("smoke hole") or lovarium (identical with Old French

louvert, "opening"). The so-called Liberate Rolls of King

Henry III, issued in 1216 and 1272 (verbal directive for

repair and construction of houses owned by the crown)

make frequent reference to these devices.[236]

Loggan's engravings

of the halls of New College and Magdalen College

show how these smoke holes were covered by a simple

saddle roof, which looks like a portion of the main roof cut

out and raised over the hole. In Loggan's Oxonia Illustrata

saddle-like louvers appear only on the roofs of the earlier

college halls. On the roofs of the later halls the saddle-like

louver was replaced by a flèche or lantern, a Gothic development

and one which the author of the Plan of St. Gall

is not likely to have envisaged.[237]

365. JEAN LE PRINCE. LES LAVANDIÈRES, 1770, PARIS

ÉCOLE DES BEAUX-ARTS, COLLECTION ARMAND-VALTON

(AFTER LE PAYSAGE FRANCAIS. 1926, PL. LV)

The saddle-like version is the simpler and, unquestionably,

the older form, and this type of fumerium is in my

opinion what the author of the Plan had in mind when he

used the term testu.

Extracts of the "Liberate Rolls" of King Henry III are published

in Turner, 1877, 181ff. For passages that bear directly on the subject,

compare in particular, Roll 32, ibid., 216-17: "The keeper of the manor

of Woodstock is ordered . . . to make a hearth [astrum] of free-stone,

high and good, in the chamber above the wine-cellar in the great court,

and a great louver over the said hearth; and to make a door under the

door of Edward the king's son, and two great louvers [lovaria] in the

queen's chamber. . . ." Roll 28, ibid., 201, to the keepers of the works

at Woodstock: "And make also in our great hall at Woodstock a certain

great louver [fumerium]"; Roll 30, ibid., 209-10: "The sheriff of Southhampton

is ordered . . . to paint and gild the heads on the dais in the

king's great hall there, and to cover the louvers [fumericios] on it with

lead"; Roll 35, ibid., 234: "The sheriff of Wiltshire is ordered to re-roof

the queen's chapel, and to repair the louver [fumatorium] above the

king's hall at Clarendon which is injured by the wind"; Roll 36, ibid.,

234-35: "The king to the sheriff of Nottingham. We command you to

block up the cowled windows [fenestras culiciatas] on the south side of

the great hall of our castle of Nottingham, and to cover them externally

with lead; and make a certain great louver [fumerium] on the same hall,

and cover it with lead."

The earliest flèche-shaped lantern over the smoke hole of a medieval

hall known to me is that of Westminster Hall, "an exact copy of the

original from the end of the fourteenth century"; see Parker, 1882, 39.

For further specimens, see Atkinson, 1937, articles "Louver" and

"Lantern," also 122, fig. 118; and Clapham and Godfrey, n.d., 131 and

figs. 50 and 56 (turret-louver of Crosby Hall, 1466).

MODERN SURVIVAL FORMS

Superstructures of this type, almost extinct in the Old

World, are a common feature of the timbered barns in the

great farm belt of the United States (fig. 363). This device

was brought over by early settlers, along with the very type

of building for which it had been invented in the Early

Iron Age. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of aisled

American hay and dairy barns of timber are ventilated even

today by openings in the roof ridge, which are shielded by

elevated sections of the main roof and which still retain the

shape of what in the Middle Ages was probably the most

common means of controlling light and smoke.

The design of such a device from a barn in the vicinity VENICE, LIBRARY OF ST. MARK'S LABORS OF THE MONTH OF JULY, DETAIL, fol. 7v [photo: Alinari 39311]

of Benicia, California (fig. 364), is probably as good a guide

for the reconstruction of the louvers of the guest and service

buildings on the Plan of St. Gall as any equivalent found in

Europe, where this particular device disappeared rapidly in

366. GRIMANI BREVIARY

367. GRIMANI BREVIARY

VENICE, LIBRARY OF ST. MARK'S

LABORS OF THE MONTH OF FEBRUARY, DETAIL, fol. 2v

[photo: Alinari 39316]

hooded chimneys, a development that must have been

nearly complete by the beginning of the fifteenth century.

Despite a thorough search among Flemish, Dutch, and

German landscape drawings, etchings, and paintings—

media which have richly and vividly preserved the architectural

panorama of the medieval countryside—I have

been able to trace only a single case of survival in post-medieval

architecture, and a belated one at that. In an ink

drawing of 1770 by Jean le Prince, entitled Les Lavandières

(fig. 365) there is shown in the center of the bridge that

crosses a stream an old rectangular house with an opening

in the ridge which is shielded by a raised portion of the

main roof above the spot where in the period of construction

of this house there must have burned an open fire.

Together with the saddle-shaped superstructures over the

ridge of the halls of New College and Magdalen College at

Oxford, this drawing of Jean le Prince may retain the most

truthful visual record of the device which in the guest and

service buildings of the Plan is referred to as testu.

368. DUTCH BIBLE (UTRECHT, 1465)

RUTH LYING WITH BOAZ

VIENNA NATIONAL LIBRARY, ms. 2177, fol. 153v.

[after Byvanck and Hoogewerff, I, 1922, 116.B]

The details of the roof flaps und the curved levers by means of which they were

opened and shut are clear enough to leave no doubt about their identity with the

18th-century examples shown in figs. 369 and 370. Observe in the background the

haystack with a roof that can be lowered and raised, a Carolingian example of

which is shown in fig. 326.F.

HINGED HATCHES

However, in the Lowlands during the sixteenth century,

there existed a related device which, judging from the frequency

of its appearance in the illuminations of the Grimani

Breviary and other Franco-Flemish manuscripts of the

same period, must also have been a common feature in late

medieval house construction. A considerable number of

houses represented in the landscapes of these manuscripts

have smoke holes covered by wooden hatches hinged to the

ridge, which could be raised or lowered by means of pulleys.

This device appears in three different places in the Grimani

Breviary: the July representation (fig. 366), the March

representation, and the well-known February representation

(fig. 367), in which a wisp of smoke can be distinguished

rising in gentle spirals into the chilly winter air from an

open fire burning directly below the smoke hole on the

simple clay floor.[238]

Again, it is depicted in the September

representations of the breviary of the Museum Mayer van

den Bergh at Antwerp[239]

and in an illustration, which depicts

ROOF FLAPS ON AN 18TH-CENTURY FARM, THE NETHERLANDS

369. CROSS SECTION

The roof flaps are shown in closed position, with cord arrangement visible.

[after Uilkema, 1916, 21, fig. VII, and 27, fig. IX]

A simple arrangement of cords and eyes or small blocks caused the right-hand cord to open the left-hand flap, and vice-versa. These cords

were cleated off below to maintain the flap open which, when released, closed of their own weight.

370. EXTERIOR PERSPECTIVE

One roof flap is open (the second is omitted from the drawing for clarity).

illuminated around 1465 (fig. 368).[240] The technical details

of how such roof flaps were operated are well explained in

the sketches of a vent of a Frisian farmhouse of the eighteenth

century, published by K. Uilkema (figs. 369 and

370).[241]

A wooden hatch or lid of this kind would be in complete

accord with the term testu ("lid"), but the dimensions of

many of the testu squares of the Plan of St. Gall, some of

which are as large as 10 feet square (Hospice of the Paupers,

House for Distinguished Guests), speak against this being

the type used. Hinged lids of such dimensions would be

unmanageable. The saddler roof is the simple and the earlier

form, and for this reason in our reconstruction of the guest

and service buildings on the Plan, we have chosen the latter

version.

Grimani Breviary, ed. Vries and Morpurgo, I, 1904, fols. 7v (July),

3v (March), 2v (February). The calendar section of this manuscript has

also been published by François M. Kelly, n.d., pls. VII (July), III

(March), II (February). In both these editions, which are in color, wisps

of smoke are clearly visible.

V.7.2

CORNER FIREPLACES WITH CHIMNEYS

A PREROGATIVE OF HIGHER-RANKING MEMBERS

OF THE MONASTIC COMMUNITY

In addition to the central open fireplace which forms the

primary—and in the majority of houses, the only—source

of heat, some of the guest and service buildings are provided

with another device for heating individual rooms. Its

symbol is an ovoid loop (fig. 371 A and B) always found in

the corner of a room. In the Abbot's House, it is designated

PLAN OF ST. GALL

371.A ABBOT'S HOUSE

371.B HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

CORNER FIREPLACES

Corner fireplaces with chimney stacks are installed in double-storied structures and

in houses where the seclusion of separate living or bedrooms deprives occupants of

the heat of the central fireplace (as in the House for Distinguished Guests).

caminata) is the medieval word for a room that has its own

fireplace (caminus).[242] In this sense the term is used to indicate

the bedrooms for distinguished guests (caminata cum

lectis; fig. 371B) and the bedroom in the Porter's lodging

(caminata portarii). By contrast, in the Abbot's living room

as well as his bedroom, both of which are heated by corner

fireplaces, the word caminata is inscribed into the interior

of the loop-shaped symbol that indicates the presence of

these heating devices, and therefore must have been used,

in these two instances, as synonyms for caminus, i.e. the fireplace

itself.

Individual fireplaces indicated in this way on the Plan CORNER FIREPLACE, BEGINNING 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. The stack of this earliest archaeologically attested corner fireplace was formed by

are found either in buildings having no central hearth, or

in rooms separated from the common hall by wall partitions

for the sake of greater privacy. Such fireplaces were the

prerogative of the higher ranking members of the monastic

polity and of the sick. They are primarily associated with

masonry structures. Besides appearing in the Abbot's

House, they are also found in the living quarters of the

monastic officials next in rank: the Porter, the Master of

372. MESOPOTAMIA, PALACE OF MARI

tubes of fired clay whose curved flanges and conical shape allowed them to fit into

one another. This ingenious flue at so early a period probably was used in houses of

the aristocracy.

of the Infirmary, and the Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers.[243]

For reasons of health they occur in

all the sick wards (Novitiate, Infirmary, House for Bloodletting,

House of the Physicians). They are found with less

frequency in the guest and service buildings. Here again

their presence is determined by considerations of rank or

functional necessity. We find them in the bedrooms of the

noblemen in the House for Distinguished Guests, in the

bedrooms of the Physician and the Gardener. Conversely,

they never occur in the buildings that accommodate the

humbler members of the monastic community. They are

completely absent from the houses for the workmen and

craftsmen, the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, and the

houses that shelter serfs or livestock and their keepers.

Du Cange, II, 1937, 52: camera in quo caminus extat. Cf. also

Murray, Dictionary II:1, 1893, 349.

The quarters of the Porter and of the Master of the Outer School

are in the row of masonry structures which are built against the northern

aisle of the Church, and in this row also are the living room and the

dormitory for the Visiting Monks, both provided with corner fireplaces.

The lodging of the Master of the Paupers' Hospice is built against the

southern aisle of the Church, next to the Hospice itself. Of other ancillary

structures of the central group of monastic buildings that are provided

with corner fireplaces, one should mention the Sacristy and the Annex

for the Preparation of the Holy Bread and the Holy Oil.

ETYMOLOGY AND SHAPE SUGGEST DERIVATION

FROM THE OVEN

Caminus comes from the Greek κάμινος, which meant an

"oven, furnace, or kiln for smelting, baking, or burning

373. LE PUY-EN-VELAY (HAUTE-LOIRE), FRANCE

WALL FIREPLACE, 12TH CENTURY

One of the earliest and most elegant of the surviving medieval fireplaces, it is set

against a flat wall, its conical hood constructed with consummate skill supported by

cusped brackets rising from two short columns.

apparently had come to mean "a furnace which supplies

the heat for a room or an apartment."[245] On the Plan of St.

Gall it is used in this sense in connection with the large

firing chambers (caminus ad calefaciendü) of the hypocausts

which heated the Monks' Dormitory and Warming Room

as well as the living and sleeping quarters of the novices and

the sick. In medieval Latin caminus is the standard term for

a wall or corner fireplace with a chimney, as may be inferred

from Old High German glossaries, where it is translated

both by "oven" (ofan) and "chimney" (scorenstein).[246] The

etymology of the term caminus—its original meaning of

"kiln" or "oven" and its eventual change to mean chimney

(French: cheminée; German: Kamin)—suggests that the

medieval wall or corner fireplace is, developmentally, an

offspring of the baker's oven or potter's kiln. This assumption

makes sense for functional as well as etymological

reasons. When the fire was moved against the wall, it had

to be enclosed, and the age-old solution for enclosing a fire

was the ovoid or round oven of the baker or potter. When

the baking oven had, in this manner, been transformed into

374. FRANKFURT-AM-MAIN, GERMANY

RÖMERTURM, CORNER FIREPLACE, 13TH CENTURY

The hood has the shape of a beehive. Other examples of this design are found

in the Berchfried of Castle Schönburg, near Naumburg (by some ascribed to the

11th century) and in the Berchfried of Petersberg near Freisach (see Piper,

1895, figs. 476 and 480).

room, the proper functioning of the fire and the health of

the people whom it served required a smoke flue. At precisely

what point in history this feature was introduced is

as yet uncertain.

375. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CORNER FIREPLACE

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

Our reconstruction of the corner fireplaces in the bedrooms of the guests is

related to the design of the chimney shown in fig. 373. The hood masonry rests

on a lintel fashioned by contilevered curved stones seated deep in the masonry,

separated on corbels likewise deeply embedded. A voussior as illustrated, or a

joint, may occur at center.

Steinmeyer and Sievers, Glossen, III, 1895, 10, No. 51 (ofan); 418,

No. 73 (eitoven); 384, No. 3 (scorenstein).

TIME OF INVENTION OR ADOPTION

IS PROBLEMATIC

Moritz Heyne[247]

and Joseph Schepers[248]

ascribe its invention

to the Romans, but this supposition has recently

been shattered by André Parrot's extraordinary discovery

of two fireplaces from the bathrooms of the Palace of Mari

in Mesopotamia, which date from the beginning of the

second millennium B.C. (fig. 372).[249]

The smoke flues of these fireplaces consist of conical [after Erikson, 1947, 427, fig. 546] CORNER FIREPLACE [after Erixon, 1947, 426, fig. 545] CORNER FIREPLACE WITH OVEN

hoods encasing a vertical stack of tubular flue tiles, with an

opening at the bottom for the fire which burned on a platform

that formed a quarter of a circle. Hence the Romans

cannot claim to be the first inventors of this device. They

may have rediscovered it, but until a chimney-type Roman

corner fireplace has actually been excavated—and so far no

one has had the good fortune to find one—even this assumption

must remain hypothetical. Conversely, it must be

stressed that wall or corner fireplaces with chimneys were

not a feature characteristic of Germanic house construction,

and were not known at all in the northernmost areas

held by Germanic peoples. We know this is so not only

because of hundreds of house sites that have actually been

376. GRYTEN, VÄSTERGOTLAND, SWEDEN

WITH DOMESHAPED

HOOD AND OVEN377. SANNAP, HALLAND, SWEDEN

SURMOUNTED BY CONICAL

HOOD

introduced at the Norwegian court during the reign of Olaf

Kyrre (1067-93), this was an event so unusual that it was

considered worthy of being recorded in Snorri's Lives of the

Kings of Norway: "It was an old custom in Norway that

the King's high seat was in the middle of the long bench.

The ale was borne round the fire. King Olaf was the first

to install corner fireplaces."[250]

(Ofnstofur, the Old Norse

term, like the Latin caminus retains etymological consciousness

of the fact that the masonry fireplace is an offspring of

the oven !) Iceland resisted this innovation even longer. The

first masonry-built Icelandic wall fireplace was constructed

in 1316, in the timbered hall of Bishop Laurentius at

Hólar.[251]

Parrot, II, 1958, 201-5. The excavations were conducted as early

as 1935-38, but publication of the results was delayed by World War II.

The report does not comment in any manner upon the historical significance

of these corner fireplaces found in rooms that also contained

several bathtubs and privies.

"Þat var siđr forn í N'regi, at konungs hásæti var á miđjum langpalli,

var öl um eld borit; en Ólafr konungr lét fyrst gera sitt hásæti a

hápalli um þvera stofu, hann lét ok fyrst gera ofnstofur" (Heimskringla,

ed. Unger, 1868, 629; and in English translation by Monsen, 1932

576).

We can infer this from a passage in the Biskupa Sögur, where it is

said of Bishop Laurentius that "he installed a stone fireplace [steinofn]

in his timbered hall at Holum, such as they were wont to have in Norway,

and made the chimney of that fireplace so large that he himself could sit

down in it" (Biskopa Sögur, ed. Sigurdsson and Vigfusson, I, 1856,

830; for the date, Gudmundsson, 1889, 179-80).

EARLIEST VISUAL & LITERARY EVIDENCE

IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE

The Plan of St. Gall, to the best of my knowledge, offers

the earliest visual evidence of the use in Europe of corner

fireplaces with chimneys. Literary evidence, however, of

such heating devices in individual rooms goes back as far

as the sixth century. In 584, in connection with a donation

to the church of St.-Marcellus ad Cabillonum (Châlons-sur-Saône),

378. MUSEÉ CONDÉ, CHANTILLY,

FRANCE

LES TRÈS RICHES HEURES DE JEAN DE

FRANCE DUC DE BERRY.

FEBRUARY: DETAIL.

The miniature depicts rural life during the month of

February, portraying a snow covered landscape with a

farmhouse, a pigeon house and a stack of beehives. Inside

the farmhouse the mistress and two servants warm themselves

before a crackling fire. The hood and mantle of the fire

place are built in masonry. The chimney shaft is braided

in wicker-work, presumably daubed inside to prevent it

from catching fire.

The manuscript, one of the finest of its kind, was illuminated

between 1411 and 1416 by Pol de Limburg, the most

distinguished of a small group of Flemish artists who,

trained in the tradition of French illumination of the

fourteenth century, under the inspiration of contemporary

Italian painting laid the foundations for the realistic style of

the brothers van Eyck.

construction of a royal guesthouse (hospitole), the description

of which (solarium cum caminata and lobia, galleried

porch) is strikingly reminiscent of both the Abbot's House

on the Plan of St. Gall and the royal residence at Anappes

of the Brevium exempla.[252]

"Censemus ergo regalique authòritate roboramus, ut ibi manentes servi

hospitale construant: solarium vero cum caminata, illi de Gergeyaco et de

Alciato faciant: illi autem de Mercureis et de Canopis lobiam aedificiint"

(Bréquigny, I, 1791, 79; the passage is quoted and discussed by Heyne,

I, 1899, 75).

EARLIEST EXTANT MEDIEVAL

CORNER FIREPLACES

The earliest extant Continental chimneys date from the

twelfth century. They form niches in the masonry walls and

are surmounted by conical hoods often braced at the sides

by pillars and brackets. They are usually constructed on a

full circular plan, the heating chamber forming the rearward,

and the hood the forward, segment of the circle. Two

typical examples of this species, dating from the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries, respectively, are found in Le Puyen-Velay

(Haute-Loire), France (fig. 373)[253]

and the so-called

379.A SAALBURG, HESSE, GERMANY. FORTIFIED ROMAN FRONTIER CAMP

"PILLARED" HYPOCAUST [after Fusch, 1910, pl. xv]

Although slow in making warmth felt in the rooms served

by the system, the hypocaust had the great advantage,

once the building was warmed by convection and

conduction, of providing through radiation from walls and

floor an even temperature for long periods of time, in

relatively large spaces, using only a small amount of fuel.

Ideally suited for the large warm and hot rooms of

Roman baths, the hypocaust was used in the northern

provinces of Rome almost universally in private homes.

This hooded circular fireplace, in my opinion, is the type

that the draftsman of the Plan had in mind when he used

ovoid symbols for the private heating units of the leading

monastic officials and the monastery's distinguished guests

(fig. 375). In this connection attention must be drawn to

certain oven-shaped corner fireplaces still in use today in

rural buildings of Sweden, two typical examples of which

are given in figure 376 and 377.[255] Both of these are, in fact,

oven and fireplace combined.

I do not doubt that the corner fireplaces of the Plan of

St. Gall were intended to be built in masonry, although

there is evidence for the existence in the Middle Ages of

fireplaces with wooden hoods. A group of wooden chimneys,

mounted on frames of oak and filled with wattle and

daub, was published in Nathaniel Lloyd's History of the

English House.[256]

We may assume that fireplaces constructed

entirely of wood or of both wood and stone were equally

common on the Continent, because of their appearance in

late medieval manuscripts and paintings. A typical example

of this mixed technique is the fireplace of the farmer's

house in the charming winter landscape of the February

representation of Jean de France's Très Riches Heures (fig.

378),[257]

and an example of a fireplace built entirely of wood

is the one at the rear wall of a wooden cottage in the Livre du

Cuer d'Amours Espris of René, Duke of Anjou.[258]

These

medieval wall and corner fireplaces with wooden chimneys

were, in my opinion, not an original conception, but rather

an adaptation to Northern building materials, performed on

a relatively humble social level, of a heating device that

formed no part of the Northern building tradition.

After Viollet-Le-Duc, III, 1868, 197, fig. 2. The fireplace is located

in a vaulted room above the porch of St.-Jean which connects the

northern forechoir aisle of the cathedral of Le Puy with its baptistery.

See Guides Bleus, Cévennes, ed. Monmarché, 1934, 75-76.

After Stephani, II, 1903, 508, fig. 264; there ascribed to the end of

the eleventh or the beginning of the twelfth century. Dehio (Handbuch.

III, 1908, 416 and III, 1925, 446) ascribes it to the thirteenth century.

For additional German examples, see Piper, 1895, 487ff. The earliest

English specimens are discussed in Lloyd, 3rd ed., 1951, 434ff. For

further information see the forthcoming doctoral thesis "The Medieval

Development of Fireplace and Chimney" by Leroy Dresbek, in process

of being submitted at the University of California at Los Angeles

(brought to my attention by Lynn White).

Lloyd, op. cit., 347. For further literary evidence of fireplaces built

of wood in Medieval England, see Crossley, 1951, 21.

Smital and Winkler, 1926, pl. VII: Cuer Enters the Cottage of

Melancholy. Another good example of a wooden medieval smoke flue

may be found in Deutsche Kunst and Kultur im Germanischen National-Museum,

1952, 82 (Birth of Maria, altar wing by the Tirolese Master

of the Uttenheim Panels, end of the fifteenth century).

WESTWARD DIFFUSION FROM THE NEAR EAST

BY-PASSING ROME?

Roman custom of heating a house or its individual apartments

by means of hypocausts stands in marked contrast

to the open fire that burned on the floor of the Germanic

house. The Roman heating unit was not only enclosed; it

was concealed. The medieval open chimney combined the

advantages of both; the fire was enclosed, as in the Roman

type, and yet it was visible, as in the Germanic open fireplace.

We do not know exactly when or where this combination

379.B ST.-REMY, BOUCHES-DU-RHÔNE (NEAR ARLES), FRANCE

RUINS OF A "PILLARED" HYPOCAUST IN A HOUSE OF THE ROMAN SETTLEMENT OF GLANUM

These two illustrations show typical use of the Roman

hypocaust system in houses of transalpine Europe. No

Roman villa of any significance in the vast stretches of

land that extended from Provence to the borders of

Scotland lacked such a facility.

it occurred in an area where Roman and Germanic culture

merged. But Parrot's discovery of corner fireplaces with

chimneys in the Mesopotamian Palace of Mari, dating as

early as the beginning of the second millennium B.C., suggests

that we have to contend with a third influence, from

the East. It is possible that the medieval wall or corner

fireplace is a Near Eastern idea, cast into Roman masonry

in Merovingian times, which permitted the installation of

open fires in individual rooms, without endangering the

safety of the building. Perhaps it was the close ties established

between the Near East and the West through the

monastic conquest of Merovingian Europe, in the fifth

century, as well as the ubiquitous presence in the ports and

inland cities of Gaul of Syrian, Egyptian and Jewish tradesmen

that opened up the channels for the westward diffusion

of this heating device which seems to have bypassed

Rome.[259]

380. SILCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND

Roman hypocaust of the channeled type. The floor of the room is removed to reveal the hypocaust substructure. This system, although not

quite so common, was as widely diffused as the pillared type.

[after Joyce, 1881, pl. vii]

On the spread of eastern forms of monasticism in western Europe

see Prinz, 1962. On the activities of Syrian, Egyptian and Jewish tradesmen

in Merovingian Gaul, see Pirenne, 1937, 57ff. (English translation

by Bernard Miall, 1968, 75ff). On the immigration of near-eastern intellectuals

caused by the Arab conquest of Syria (634-636) and Egypt

(640-642) see Pirenne, 1937, 62ff (English translation, 79ff). On the

Syrian and Egyptian influence on the Art of the Migration period, see

Holmqvist, 1939, 190ff. It is a well-known fact that even after the

Moslems had closed the Mediterranean sea lanes pilgrims continued to

flock to the holy places of Palestine (Pirenne, 1937, 143ff; English translation,

164ff).

V.7.3

HYPOCAUSTS

TWO TRADITIONAL ROMAN TYPES:

CHANNELED AND PILLARED

Since the history of the Roman hypocaust has been fully

documented elsewhere, we may confine ourselves here to

the most summary review.[260]

This heating system, developed

to perfection by the Romans, is found not only in their

baths but also in practically every Roman villa north of the

Alps. The Roman hypocaust was either of the channeled

or the pillared type.[261]

In the latter, a good example of which,

from the Roman camp Saalburg, is shown in fig. 379, the

floor of the room to be heated was raised by short columns,

usually two feet high, a shallow chamber thus being formed

below the floor level. The heat, generated in a furnace that

was built against one of the outer walls and serviced from

the outside, was dispersed into this chamber and rose from

there in vertical flues imbedded in the walls. In the other

type, hot air was taken from the furnace through a trench

beneath the floor to the center of the room and then diverted

radially to the four corners into a channel running all the

way around the room, at the bottom of the walls, from which

point it rose into the wall flues, as in the hypocaust from a

building in block II of the Romano-British city of Silchester

(fig. 380).[262]

For a detailed treatment, see article "Hypocaustum" and bibliography,

in Pauly-Wissowa, IX:1, 1914, cols. 333-36; for a more summary

treatment, Singer, Holmgard, Hall, and Williams, II, 1956, 419ff.

On Silchester see James Gerald Joyce, 1881, 329ff. An interesting

example of the channeled type has recently been excavated beneath the

floor of an apsidal reception room in the late Roman Imperial villa at

Konz, near Trier (fig. 241). It consisted of a firing chamber located more

or less in the center beneath the room, serviceable from the outside by a

narrow tunnel, and five large ducts fanning out toward the periphery

of the room where they fork into smaller channels terminating in outlets

in the four walls of the room. For a plan of the entire villa see I,

p. 294, fig. 241A; for further details, see the excavation reports cited

above, I, p. 317, note 27.

THE CHANNELED HYPOCAUST OF THE

MONKS' DORMITORY

On the Plan of St. Gall only those parts of the hypocaust

are shown which lie outside the warming rooms, namely

the furnaces and the chimneys (fig. 381). We are told

nothing about the layout of the ducts and flues that distributed

the heat in the rooms themselves. To do this in the

calefactory of the monks would have been impossible, as it

would have obscured the layout of the beds in the Monk's

Dormitory, which the drafter of the Plan considered to be

of greater importance. But in the warming rooms of the

Novitiate and the Infirmary, with no story above, he could

have gone into detail. Since he chose not to do this, it then

becomes clear that in his day the construction of a hypocaust

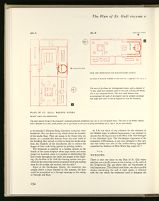

381.A PLAN OF ST. GALL. FIRING CHAMBER & SMOKE STACK OF HYPOCAUST

MONKS' WARMING ROOM

see INDEX TO BUILDING NUMBERS OF THE PLAN VOL. I page xxv, VOL. III page 14

The hypocaust services a two-storied

structure, 40 feet wide and 85 feet long,

which contains on the ground floor the

Monks' Warming Room and on the upper

level the Dormitory. Of the heating system

itself only the firing chamber and the smoke

stack are shown. Their existence at two

opposite ends of the building postulates the

presence of a system of connecting ducts in

the subfloor which provides for draft to

distribute the heat and allows the smoke to

escape through a smoke stack placed at a

safe distance from the main structure.

no further instruction.

The furnaces are designated by the words fornax see INDEX OF BUILDING NUMBERS OF THE PLAN Only one room of the Novitiate and

(cloister walk in front of the Monks' Calefactory), caminus

ad calefaciendū (firing chamber of Monks' Calefactory),

and camin' (Novitiate); the smoke flues, by euaporatio fumi

(Monks' Calefactory) and exitus fumi (Novitiate). There

is no reason to assume that the furnaces were meant to lie

directly beneath the floor of the rooms they heated.

Nowhere else on the Plan has the architect designated

anything at the side of a building which was meant

381.B WARMING ROOM OF THE NOVITIATE

Infirmary is heated by a hypocaust. Others

of virtually identical dimensions are heated

by corner fireplaces. The choice was clearly

conditioned by the need for a room in each

of these facilities with an even and constantly

maintained temperature.

382.A PLAN OF ST. GALL: BAKING OVENS

MONKS' BAKE AND BREWHOUSE

The daily need for bread of the monastery's planned permanent inhabitants was 250 to 270 one-pound loaves. The oven in the Monks' Bakery

with a diameter of 10 feet, could produce 300 to 350 loaves in one cycle of firing and baking (see p. 259 n. 26 for more detail).

traditional. Nor can there be any doubt about the location

of the smoke flues. They are meant to be where they are

shown: at a considerable distance from the outer walls of

the buildings they served, in order to keep the smoke away

from the windows of the dormitories and to reduce the

danger of their roofs being ignited by glowing cinders.

The hypocaust is superior as a heating system to the

hearth or the corner fireplace when large rooms and many

people are involved, since it is capable of distributing the

heat evenly throughout the width and length of the building.

On the Plan of St. Gall this heating system was provided

for the rooms that served as general work and reading

areas for the monks, the novices, and the sick.[263]

Since in the Carolingian cloister, the dormitory was

usually above a room warmed in this manner, the heat

could be transmitted to it through openings in the ceiling

or through wall flues.

382.B BAKE AND BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

see INDEX OF BUILDING NUMBERS OF THE PLAN VOL. I, page xxiv; VOL. III, p. 14

The oven of the House for Distinguished Guests, with a diameter of

7½ feet, could have produced easily in one cycle of firing and baking

200 to 250 one-pound loaves. The oven could therefore have

accommodated the needs of the emperor and his complete entourage

who might from time to time be expected to visit the monastery.

As I do not know of any evidence for the existence in

the Middle Ages of pillared hypocausts, I am inclined to

assume that the hypocausts of the Plan of St. Gall belonged

to the channeled type. The Carolingian hypocaust of the

monastery of Reichenau, at any rate, belonged to this type,

and this holds true also of the tenth-century hypocaust

unearthed by Seebach at Pfalz Werla (fig. 209A-C).[264]

Cf. above, I, 253ff (Monks' Warming Room), I, 313ff (Warming

Room of the Novices, ibid., (Warming Room of the Sick); also what

Adalhard has to say on the use of the Warming Room, I, 258.

V.7.4

WINDOWS

There is only one place on the Plan of St. Gall where

windows are actually shown in the drawing: in the walls of

the Scriptorium (fig. 99) where they are functionally of

vital importance. The symbol used there, two short parallel

strokes intersecting the wall at right angles, is identical

with the one which the draftsman used to designate the

382.C BAKE AND BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

The number of visitors expected to lodge each night in the Hospice

for Pilgrims and Paupers may not have exceeded twelve (see below,

p. 144). But if customs prevailing at the monastery of Corbie

reflected general conditions, these transient guests were issued bread

rations considerably larger than were allotted to the monastery's

regular inhabitants: 3½ pounds per person upon arrival, and half

that amount on departure. For a complement of twelve guests this

distribution would amount to 63 pounds of bread each day. During

the great religious festivals these amounts rose steeply as the number

of travellers increased; even under ordinary conditions it would have

been necessary to add to the needs of the overnight guests those of

the transients who might stop for a noon meal and then move on.

This explanation would account for the large size of the Hospice

oven, its 7½-foot diameter being identical to the oven of the House

for Distinguished Guests.

the line that defines the course of the walls is not interrupted

by these strokes as it is in the majority of the entrances,

doors, and exits. In other buildings, such as the Church,

the Abbot's House, or the large complex that contains the

Novitiate and the Infirmary and their chapels, windows

were so clearly an integral part of the building type that the

draftsman felt it unnecessary to go into any detail in this

matter.

In the case of the guest and service buildings, however, NEOLITHIC BAKING OVEN [after Adrian, 1951, 69, fig. 2] 384.A 384.B LANGOBARDIC BAKING OVEN [after Adrian, 1951, 69, fig. 2] This later oven, retaining the daubed wattle shell of its ancestor (fig. 383), MONUMENT OF THE BAKER EURYSACES. DETAIL. FIRST [after Singer et. al, II, 1956, 118, fig. 88] The frieze appears on the funerary monument of a wealthy plebeian master

conditions were different. Traditionally, this type of house

was not provided with windows. Lighting, ventilation, and

383. TAUBRIED AM FEDERSEE, Wurttemburg,

GERMANYLANGENBECK, HARBURG, GERMANY

reveals a sophisticated awareness of heating insulation, with its boulder-lined

fire and baking chamber sunk below the surface of the ground.385. ROME

CENTURY B.C.

baker who prospered during the final years of the Republic. The oven appears

in a form it has retained into modern times.

MESOPOTAMIA, PALACE OF MARI. BAKING OVEN

386.A

386.B

BEGINNING OF 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C.

in the roof. This does not categorically preclude the use

of wall windows. As the need for higher degrees of privacy

led to the installation of corner fireplaces as secondary

sources for heat in rooms that were segregated from the

common hall by internal walls and ceilings, so the separation

of these rooms from the central source of light made necessary

the installation of supplementary devices for the

admission of light and air. This could take the form either

of wall windows or of dormer windows.

In the guest and service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall, 386.C ELEVATION OF OVEN OPENING PLAN AND SECTION The oven, located in the commoners' quarters, was 2 feet larger in diameter

accordingly, we may have to take into account the entire

range of possibilities, from complete absence of windows

on the lower levels of dwellings (the houses of the serfs and

the houses of the animals and their keepers) to the presence

of some windows in the rooms of the higher-ranking monastic

officials (such as the Gardener, the Physician, the Porter,

than that of the oven of the Monks' Bake and Brewhouse (fig. 382). It was

built of both fired and unfired bricks set with mud joints—a technique that

can be traced in the Near East to the middle of the 4th millenium B.C. The

dome-shaped shell, presumably built in corbelled horizontal courses of brick,

had collapsed. It rose from a well-preserved circular foundation of large

bricks. The oven opening was formed by two arched courses of bricks radially

set which survived in perfect condition.

fenestration on the highest level of dwelling (such as the

House for Distinguished Guests; or in the Outer School,

where supplementary light inlets were a functional necessity).

The small squares in the cubicles for the students of

the Outer School, as we shall subsequently show, must

probably be interpreted as symbols for dormer windows.

V.7.5

BAKING OVENS

On the Plan of St. Gall there are three baking ovens (fig.

382A-C): one in the Monks' Bake and Brew House

(caminus); one in the Bake and Brew House for Distinguished

Guests (fornax); and one in the Bake and Brew

House for Pilgrims and Paupers (fornax). They have diameters,

respectively, of 10 feet, 7½ feet, and 7½ feet.

387. KARKÓW, POLAND. BEHAIM CODEX (1505). BAKEHOUSE WITH OVEN, KETTLE, AND KNEADING TABLES

JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX PICTURATUS, fol. 246. [after Winkler, 1941, Pl. 4]

The Behaim Codex is a compilation of privileges, oath formulae, and guild ordinances written in German. It is named from an annotation on

the title page by the clerk and notary of Kraków, Balthasar Behaim (d. 1508), which reads: Anno domini 1505 consummatum. Written

and illuminated in strong and radiant colors by a local artist, doubtlessly of German descent, the manuscript has stylistic roots in a school of

illumination that flourished in Augsburg and Nürnburg, and was strongly influenced by the work of Albrecht Dürer. The representation of the

bakehouse appears on folio 246. Its title is written in bold red letters. (Winklers' color plate suggests that the roof may have been sheeted in

copper.)

388. TÜBINGEN, WURTTEMBURG, GERMANY. UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX M. D. 2, fol. 29V

This detail shows the planet-children of Saturn in furious, cheerful dispatch of the tasks of baking: milling, kneading dough and setting loaves

to rise, loading the familiar domed oven. Pastries may have been the fate of the caged birds. (Panofsky and Saxl treat the complex iconography

of this illumination in Dürer's "Melencolia I", Leipzig, 1923, 61 [Studien der Bibliothek Warburg]. The codex dates to the late 15th century.

The baking of bread is one of the most ancient of human

arts. Calcined remains of unleavened bread made from

crushed grain were found in Swiss lake dwellings that date

from the early Stone Age.[265]

Reference by implication to the

custom of leavening (i.e., admixing to the dough a substance

that produces gases, thus causing the bread to rise)

is made in Genesis, where it is said of Lot that "he made

them a feast, and did bake unleavened bread."[266]

One very

early baking method, perhaps the first devised, was that of

placing the dough on a heated flat or convex stone and

covering it with hot ashes.[267]

The size and number of loaves

that could be baked in this manner was limited by the shape

of the stone. To bake in quantity required the invention of

the oven, a round or ovoid chamber that held the heat and

allowed it to be distributed over a wider surface. One of the

earliest Central European ovens was excavated in the Stone

Age settlement of Taubried, on Lake Federsee, Germany

(fig. 383).[268]

The walls of the baking chamber were made of

daubed wattle. The opening in front was covered with a

removable shutter, probably of wood and cloth.

Between the third millennium B.C. and the middle of the

nineteenth century A.D., neither the shape of the oven nor

the method of baking changed significantly. A circular oven

of baked brick, dating from the beginning of the second

millennium B.C., was found by André Parrot[269]

during his

excavation of the Palace of Mari, Mesopotamia, (fig. 386)

in a bathroom of the quarters of the superintendent of

the palace (cf. fig. 372). A Roman oven shaped exactly like

this one is shown on a frieze of the monument of the baker

Eurysaces at Rome, dating from the first century B.C. (fig.

385).[270]

On the left, the baker is placing the loaves in the

oven. On the right, four men are kneading dough on a table.

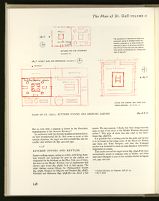

389. A, B, C, D PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN STOVES AND BREWING RANGES

In each building the stove is indicated as a square, with or without openings for pots; in all probability the "fornax super arcus" of the Monks'

Kitchen was the type in the other kitchens. The brewing ranges show corner openings for vats. The association of baking and brewing facilities

under one roof is traditional and consistent on the Plan; functional interdependence of the two crafts can be shown (see below, pp. 249ff).

still in use today[271] and were unquestionably common in

medieval times. Figure 384 shows the reconstruction of a

Langobardic oven of this type from the first century A.D.[272]

A handsome illustration in the Behaim Codex in Krakow

(fig. 387)[273] shows the baker placing the loaves in the oven,

his helper shaping them, and a woman throwing some salt

or herbs into the dough rising in a kettle on the floor in

front of the oven. The oven is built into the corner of this

copper-roofed shed. The smoke rises from a round hole in

the top of the oven and passes through a dormer window

in the roof out into the open. Figure 388 shows a baking

scene that occurs among the representations of the planet

children of Saturn in a manuscript in the University Library

at Tübingen.[274] Here again the smoke escapes through circular

openings in the top of the baking chamber. Ovens of

this same design are found in other medieval illuminations.[275]

389. E, F, G PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN STOVES AND BREWING RANGES

representation of the Grimani Breviary.[276]

In conformity with the pictorial tradition reviewed above,

we have reconstructed the St. Gall ovens as more or less

circular chambers, the larger one with a smoke flue, the two

smaller ones without (cf. figs. 402 and 394).

I cite as typical examples the representations of ovens in the

Sachsenspiegel (von Künssberg, 1934, 59) and a Hebrew manuscript of

1480-1500 (Anzeiger für Kunde deutscher Vorzeit, 1880, vol. 5 fig. 6).

V.7.6

KITCHEN STOVES AND KETTLES

Square cooking ranges, resting on arches, with firing chambers

beneath and openings for pots on the surface are

designated for the kitchens on the Plan. Only one of them,

the stove in the Monks' Kitchen, has an explanatory title

(fornax super arcus) (fig. 389A). It is 7½ feet square. The

other kitchen stoves—House for Distinguished Guests

(fig. 389B), Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers (fig. 389C),

Novitiate and Infirmary (figs. 389D,E)—are about 5 feet

square. We may assume, I think, that their design was the

same as that of the stove in the Monks' Kitchen discussed

earlier.[277]

This type of stove was also used in the brew-house

(fig. 389F,G).

It is possible that a cooking area for the serfs and laymen

is to be found in the living room of the House for Horses

and Oxen and Their Keepers, and that the H-shaped

symbol was intended to mean an open fireplace with kettles

suspended on cranes.

The circles around the larger stoves (fig. 389A,F,G) were

undoubtedly meant to indicate tubs or kettles, and these

may have belonged to any of the varieties shown in figures

210, 390, and 400.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||