The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. | V. 2 |

| V.2.1. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 2

PREHISTORIC, PROTOHISTORIC

& EARLY MEDIEVAL PROTOTYPES

OF GUEST & SERVICE BUILDINGS

OF THE PLAN OF ST. GALL

V.2.1

LITERARY EVIDENCE

THE NORTH GERMANIC HOUSE OF THE

SAGA PERIOD

In 1889 the Icelandic literary historian and philogist

Valtyr Gudmundsson[50]

was able to demonstrate, on the

basis of a careful and painstaking analysis of words and

passages in the Nordic Sagas referring to the layout and

construction of houses, that the Germanic standard house

of the Saga Period (ninth to thirteenth centuries) in Norway,

Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland was a three-aisled

timber structure with an open fireplace (eldr, "fire" or

arinn, "hearth") in the middle of its center aisle (golf);

that this house received its light through an opening in

the roof (ljóri, "light inlet"), which also served as a smoke

outlet (hence also referred to as reykháfr or reykberi, "smoke

hole,") and which could be closed and opened by means of

ropes or poles; that the roof (ráf or ræfr) of this house

was supported by a free-standing inner frame of timber,

composed of two longitudinal rows of uprights (súlur,

stafir, stođir, stolpar, and sometimes more specifically referred

to as innstafir or innstolpar, "inner posts," in contradistinction

to the útstafir, the corresponding "outer" or

"wall posts"), which were connected lengthwise by means

of roof plates (ásar or langvidir, "long beams") and crosswise

by means of tie beams (vagl, vaglbiti or þvertrè,

"crosstree"). Gudmundsson summarized his findings

visually in a plan and a perspective view of the interior of

the Saga house, drawn up for him by E. Rondahl (figs. 284

A-B).[51]

He demonstrated that this house type could be used

for a variety of purposes, without changing any of its basic

dispositions. It served, as circumstances demanded, as a

general living house (stofa or stufa), as a dining or festal

hall (drykkjuskáli, veizluskáli), as kitchen or fire house

(elda skáli), as sleeping hall (skáli or hviluskáli), even, as a

hay or cattle barn (hlađa or fjóshlađa). In the early days—

and subsequently in the lower social strata—all these functions

were performed simultaneously under one roof; later,

as increasing wealth and social prestige permitted, they

were progressively relegated to separate buildings.

Gudmundsson could establish that in the general living

house as well as in the festal or banqueting hall the floors

of the aisles (langpallar) and of the cross bay at the upper end

of the house were, in general, raised above the level of the

center floor and covered with wooden planks. Long benches

(langbekkir) and tables (borđ) were set up in the aisles

parallel to the two long walls of the house and also crosswise

along the gable wall at the rear of the house. This raised

section at the innermost part of the house was referred to as

the crossbench (þverpallr).

The chieftain or owner of the house sat on his high seat

(œdra öndvegi, "first seat of honor") in the middle of one

of the two long benches (i miđju bekk) while his principal

guest of honor occupied the second best high seat (úœdra

öndvegi) in the middle of the opposite bench. The women sat

on the crossbench at the rear of the house. The fire

crackled in the middle of the center floor. The entrance lay,

in general, in the center of one of the two gable sides of the

house, and was often separated from the rest of the house by

an entrance hall (forstofa, forskáli) which occupied the foremost

bay of the house, forming a counterpart to the women's

cross bench at the opposite gable. Often this entrance bay

was separated from the main space by a cross partition

(þverpili), which had in its center a second or inner door.

The walls of the Saga house (veggir, or, more specifically,

langveggir, "long wall," and gaflveggir, "gable walls") were,

as a rule, constructed of earth or turf (torfi), and insulated

inside with a wooden paneling (veggþili). The rafters rose

from wall plates (syllr or staflægjur) and converged at the

top in a ridge beam (mœniáss) which was carried by short

king posts (dvergr, "dwarf post") rising from the center of

the tie beams.

From numerous incidental references to the house, made

in the dramatic accounts of battles waged when a householder

and his family were attacked in their sleep and

forced to rise to defend themselves, Gudmundsson could

infer that the sleeping house (skáli) was divided lengthwise,

like the stofa, into a center aisle and two lateral

aisles and received its warmth from an open fire that burned

in the middle of the center floor. As in the stofa, the floors

of the lateral aisles were raised above the level of the center

aisle and covered with wooden planks. But instead of

supporting tables, the aisle floors of the skáli (called set)

were covered with a bedding of straw and subdivided

crosswise into individual sleeping compartments by means

of rugs or "hangings" (sængarklæđi) suspended from cross

beams. Each compartment was sufficiently large to accommodate

two people (sengefeller, "bedfellows") lying parallel

to the walls of the building, one outside (fyrir ofan) or near

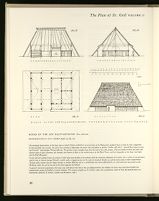

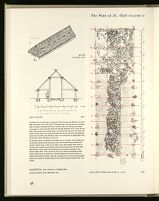

284.A THE NORTH GERMANIC HOUSE

OF THE SAGA PERIOD, 9TH-13TH CENTURIES

[after Rosenberg, 1894, 257, fig. 9]

The house is entered through one of its gable walls. Its center floor

(a,a) is made of stamped clay; b,b,b are open fireplaces framed by

stones. The aisles are slightly raised (c,c) and covered with wooden

boards. They accommodate the benches and tables for the men (f,g).

The terminal bay, with the benches and tables for the women (e.g)

is treated in the same manner; h is a table from which food and

drinks are served; i,i are footstools in front of the high seats; j is a

secret door for escape through an underground channel should the

principal entrance be blocked by enemies. The walls are built in a

mixture of earth, rubble and turves.

or near the sleeper beam (vid stokk, i.e., the floor beam that

forms the edge of the slightly raised level of the aisles). The

bedsteads of the master and his wife were often separated

from the adjoining bedsteads by means of a wooden wall

partition, so as to form a bed closet (rekkja) that could be

locked and was then called a lokhvílu (lockable closet). One

or two further closets of this type were frequently installed

for persons next in rank or for guests of honor.

In like manner the aisles of the cattle barns were subdivided

into individual cross compartments for the stabling

of the livestock.

As one reviews this evidence one cannot fail to be struck

by the amazing similarity of the North-Germanic Saga

house, spatially and functionally, with that of the guest and

service structures of the Plan of St. Gall. Both have as

nucleus an open center space accessible to all, which gives

admittance to a peripheral suite of outer spaces surrounding

the center space on three or all four sides. In both, the

hearth lies in the middle of the center space and has in

the roof above it a shielded opening that serves as a smoke

outlet. In both this layout is used, either separately or

combined, without requiring the slightest alterations of its

basic dispositions, as shelter for the people, as shelter for

their livestock, and as shelter for the harvest.

There are, to be sure, some distinctive differences. The

Saga house has its entrance, in general, in the middle of one

of its gable walls; that of the St. Gall House is, in the

majority of cases, in the middle of one of its long walls. Yet

three of the St. Gall houses belong to the former type.[52]

Another difference is to be found in the fact that in such

buildings as the House for Distinguished Guests and the

Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, the tables and benches

are ranged around the periphery of the center space (figs.

392 and 396). In the Saga house they are set up in the

aisles and on the cross bench. Only on extraordinary

occasions, namely, when the throng of visitors was so

great that they could not all be accommodated in the aisles

and on the cross bench, were special rows of chairs set up

in the nave of the hall. A typical case in point is the fateful

wedding banquet given in the winter of 1253 in Gizur

Thorvaldsson's home at Flugumyr (figs. 328A-B). The

number of guests attending this party amounted to well

over a hundred men (á œdra hundradi). Since Gizur's dining

hall was only 26 ells long and 12 ells broad (stofan var

sex álna ok tottugu löng, en tólf alna breiđ), the host gave

orders that in addition to all the seats that could be placed

in the aisles (the seating capacity of the aisles and of the

cross bench had already been doubled by the setting up of

an outer row of forechairs), two further rows of stools

should be set up in the center aisle. The latter were borrowed

from the church. "And lengthwise all along the

two benches there were forechairs and all along the center

aisle church stools were set up on which people sat in two

rows."[53]

Finally, the outer spaces of the St. Gall house

appear to have been more rigidly separated from the center

space than was the case in the house of the Sagas. But of

this there will be more to say in a later chapter.

284.B THE NORTH GERMANIC HOUSE OF THE SAGA PERIOD, 9TH-13TH CENTURIES

PERSPECTIVE VIEW OF INTERIOR, MADE FOR V. GUDMUNDSSON by E. RONDAHL [after Rosenberg, 1894, 257, fig. 10]

The hall was warmed by a fire burning in the middle of the center floor. An opening in the roof above the hearth served as smoke escape and

admitted light and air to the interior. In the aisles on either side of the fire: to the left the high seat of the owner, to the right the seat for his

most distinguished guest. Between them: the high seat pillars, part of the roof-supporting frame of timbers, but decoratively carved and sacred

to the gods.

Gudmundsson, 1889. A brief popular summary of the results of this

work was published by the same author in Rosenberg, 1894, 251-74.

I am confining myself here to the briefest summary of Gudmundsson's

findings. Anyone interested in particulars will find his way to the

original sources by checking the Old Norse terms, here given in parentheses

after their modern English equivalent, against the Old Norse

subject index at the end of Gudmundsson's book (258-66).

Not included in Gudmundsson's original study, but first published

in Rosenberg, op. cit., 257, fig. 10, and 260, fig. 11.

The House of the Fowlkeepers, the House of the Physicians, and the

large anonymous building to the left of the road leading to the monastery

entrance are all accessible through an entrance that is located on one of

the narrow ends of the building.

"Forsaeti vóru fyrir endilöngum bekk hvaramtveggja. Kirkjustólar vóru

settir eptir midju gólfinu, ok par var setiđ at tveimmegin." The account of

this banquest is to be found in Sturlunga Saga (ed. Vigfusson, II, 157ff;

and in the German translation of Baetke, 1930, 301ff; see also Baetke's

chronological table, 354). Also see below, p. 80, caption to fig. 328.

THE EARLY MEDIEVAL HOUSE IN THE TERRITORY

OF THE ALAMANNI, THE BAJUVARIANS, AND

THE FRANKS, IN THE

LIGHT OF CONTEMPORARY LEGAL CODES

Gudmundsson's findings are restricted to the Germanic

territories of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland,[54]

and cannot, of course, be automatically applied to continental

THE NORTH GERMAN HOUSE OF

THE SAGA PERIOD, 9th-13th CENT.

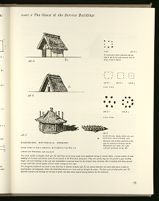

285.B EXTERIOR VIEW

285.A INTERIOR VIEW

[author's interpretation modified from Walter Schultz]

These sketches attempt to render the appearance of a typical house

of the Saga Period and to demonstrate in particular that the house

received its air and light not through windows in the walls (which

would have made the dwelling too vulnerable to hostile intrusion)

but through an opening in the roof, which also served as smoke

escape and was itself surmounted by a small roof raised slightly above

the level of the main roof. The walls were built of turves and often

even the roof itself was covered with them (cf. fig. 292), blending

house and landscape in a continuous carpeting of grass.

complex. Fortunately the information that Gudmundsson

could extract from the Sagas can be supplemented by some

extremely informative Continental sources. Significant documentary

evidence concerning house construction in the

territory of the Alamanni, the Bajuvarians, and the Franks

is scattered through a number of early medieval legal codes

that regulate, among other matters, the compensation to

be adjudged for damage wrought upon a dwelling and its

sundry appendages.[55]

LEX ALAMANNORUM

The earliest document of this nature is the so-called Lex

Alamannorum, an Alamannic code of law laid down between

716 and 719 by an assembly of thirty-four dukes, thirty-three

bishops, and sixty-five counts, under the presidency

of Duke Lantfrid I (d. 730).[56]

Article 82 of this code, which

fixes the compensation for arson, bears out what Tacitus

had stated some seven centuries earlier about the loosely

scattered character of Germanic settlements. This article

establishes the following sanctions:[57]

If at night a man sets

somebody's house (domus) or hall (sala) on fire and is

caught and found guilty, he is bound not only to restore

whatever he has destroyed by fire but, in addition, to pay a

fine of 40 shillings. If he lays fire to any other houses in the

yard (in curte), viz., the barn (scuria or granica) or the

storehouse (cellarium), he must likewise compensate for the

inflicted damage and settle with an additional fine of 21

shillings.

Fines are specified in the same manner for damage and

destruction to all the other service structures, the bathhouse

(stuba), the sheepfold (ovilis), and the pigsty (porcaricia),

as well as the houses and barns for the serfs (servi

domus, scura servi, spicaria servi). From this it follows that

century consisted of a group of separate buildings in a

common yard (curtis); its principal structures were the

house (domus) and the hall (sala). Whether domus and sala

are synonymous or indicate a separation of the principal

unit into a living house (domus) and an eating hall (sala)

remains uncertain.

From another passage in the same Lex Alamannorum

we gather incidentally some insight into the inner architectural

layout of such a dwelling. Article 94 states that if a

mother dies in childbirth, leaving a child who expires

after having lived for one hour and opened his eyes during

this time so that he could see the ridge (culmen) and the

four walls (iv parietes) of the house, the maternal inheritance

will fall to the father.[58]

This stipulation presupposes a

building open to the roof with internal subdivisions, whatever

they might have been, that did not obstruct the

simultaneous visibility, from the mother's bedstead, of the

four walls of the house and of the ridge of its roof.[59]

The latest edition of the Lex Alamannorum, including a German

translation, is K. A. Eckhardt, 1934. For previous editions and literature

concerning date and origin of the Lex Alamannorum, see the article

"Germanic Law" by Christian Pfitzer and K. A. Eckhardt in Encyclopedia

Britannica, X, 1941, 211.

1. Si quis aliquem foco in noctem miserit, ut domum eius incendat seu

et sala sua et inventus et probatus fuerit, omnia qui ibidem arsit, similem

restituat et super haec XL solidos conponat.

2. Si enim domus infra curte incenderit aut scuria aut granica vel

cellario, omnia simile restituat et cum XII solidis conponat.

3. Si quis stuba, ovilem, porcaricia domum alequis concremaverit,

unicuique cum III solidis conponat et similem restituat.

4. Servi domo si incenderit, cum XII solidis conponat et similem restituat.

5.

Scura servi si incenderit, cum VI solidis conponat et similem restituat.

6.

Si enim spicaria servi incenderit, cum III solidis conponat [et si

domino, cum VI et similem restituat] (Eckhardt, 1934, 58-59).

1. Si quis mulier qui hereditatem suam paternicam habet post nuptum et

prignans peperit puerum et ipsa in ipsa ora mortua fuerit et infans vivus

remanserit tantum spacium vel unius horae possit operire oculos et videre

culmen domus et IV parietes, et postea defunctus fuerit, hereditas materna

ad patrem eius perteneat. Tamen si testes habet pater eius qui vidissent illum

infantem oculos aperire et potuisset culmen videre et IV parietes, tunc pater

eius habeat licenciam cum lege defendere; cui est propriaetas, ipse conquirat

(Eckhardt, 1934, 66-67).

LEX BAJUVARIORUM

Information of a considerably more specific nature can be

obtained from the Lex Bajuvariorum. This code of law,

which is slightly later than the Alamannic Law, on which

it draws in part, was compiled between 740 and 748 at a

time when the territory of the Bajuvarians was already

under the firm control of the Franks.[60]

Article 10 deals with

arson and the compensation imposed for the destruction of

buildings or their component structural parts by fire or any

other means. The information contained in this article is

so vital to the history of early medieval house construction

that it deserves to be quoted in full:

BRONZE SCANDANAVIAN ORNAMENT. LATE IRON AGE (6TH CENTURY)

UPPLAND. Length 10cm. Redrawn from Marten Stenberger.

ARTICLE 10

De incendio domorum et eorum conpositione.

1. Si quis super aliquem in nocte ignem inposuerit et incenderit

liberi [vel servi] domum, inprimis secundum qualitatem personae omnia

aedificia conponat atque restituat, et quicquid ibi arserit, restituat

unaquaeque subiectilia. Et quanti liberi nudi evaserint de ipso incendio,

unumquemque cum sua hrevevunti conponat; de feminis vero

dupletur. Tunc domui culmen cum XL solidis conponat.

2. De scoria vero liberis, si conclusa parietibus et pessulis cum clave

munita fuerit, cum XII solidis culmen conponat; si autem septa non

fuerit, sed talis quod Baiuvarii scof dicunt, absque parietibus, cum VI

solidis conponat.

De illo granario, quod parc appellant, cum IV solidis conponant.

De mita vero, si illam detegerit vel incenderit, cum III solidis

conponat.

De minore vero, quod scopar appellant, cum I solido conponat.

Et universa parilia restituatur.

3. De minorum aedificiorum, si quis desertaverit aut culmen eiecerit,

quod saepe contingit, aut incendio tradiderit, uniuscuiusque quod firstfalli

dicunt, quae per se constructi sunt, id est balnearius, pistoria, coquina

vel cetera huiusmodi, cum III solidis conponat et restituat dissipata vel

incensa.

4. Si autem ignem posuerit in domum, ita ut flamma eructuat, et non

perarserit et a familiis liberata fuerit, unumquemque de liberis cum sua

hrevavunti conponat, eo quod illos inunwan, quod dicunt, in disperationem

vitae fecerit, et non conponat amplius nisi tantum quantum

ignis consumpserit.

Ducalis vero disciplina integer permaneat. Et si negare voluerit de

istis, cum campione se defendat aut cum XII sacramentales iuret.

De servorum vero firstfalli uniuscuiusque ut manus recisa conponat.

5. Modo qui [de] domorum incensione sermo perfinitum censemus,

incongruum non est, ut de dissipatione domui aedificiorum conpositione

non edisseremus.

6. Si quis relicti vel quolibet causa, per presumptionem vel inimicitiam

nec et incurie aut certe ebitione, liberi culmen eiecerit, domini domui XL

solidos conponat.

7. Si eam columnam a qua culmen sustentatur, quam firstsul vocant,

cum XII solidis conponat.

8. Si interioris aedificii illam columnam eiecerit quam winchilsul

vocant, cum VI solidis conponat.

9. Ceterae vero huius ordinis conponantur cum III solidis.

10. Exterioris vero ordinis columna angularis cum III solidis

conponat.

11. Illas alias columnas huius ordinis singulas cum singulis solidis

conponat.

12. Trabes vero singuli cum III solidis conponat.

13. Exteriores vero quas spanga vocamus eo, quod ordinem continent

parietum, cum III solidis conponat.

14. Cetera vero, id est asseres, laterculi, axes ve quicquid in aedificio

construitur, singula cum singulis solidis conponat.

Et si una persona haec omnia commiserit in alterius aedificio,

amplius non cogatur solvere quam culminis deiectione vel ea quae

maiora huius commiserit criminis; minora huius personae non secuntur,

nisi tantum restituendi secundem legum.[61]

286. HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM

8th CENTURY

RECONSTRUCTION BY KARL GUSTAV STEPHANI

[I, 1902, 326; redrawn]

Stephani correctly interpreted WINCHILSUL ("columna angularis")

and "caterae columnae huius ordinis" as, respectively, cornerpost

(A-A) and posts standing in the walls connecting them (B-B). Not

mentioned in the text and therefore purely arbitrary are entrances

to porch and main house (D, E), hearth (F), and porch itself (L-L).

The "columna a qua culmen sustentatur quam firstsul vocant"

Stephani correctly interpreted as ridge post (C), but incorrectly

presumed that it referred to a single massive timber erected in the

center of the living space. He also overlooked the reference in the

text to an inner order of posts ("ordo interioris aedificii").

The scale of Stephani's plan as it is drawn seems illogical. Evidence

from site excavations supports the contention that a ridge post such

as he postulates could not have been larger than ca. 18″ × 18″.

This dimension, applied to his drawing as a scale indicator, would

make his proposed living space about 14 feet square, or drastically

less than that needed to accommodate a Bajuvarian freeman's

family and servants. As a diagram, the plan is wholly deceptive with

little of constructive value.

ARTICLE 10

On arson and the compensation payable therefor.[62]

1. If someone sets fire at night to somebody's property, and

ignites the house of a free man (or of a serf) he is bound, first of all,

to pay a fine according to the rank of the person and make restitution

for all of the buildings; and whatever he sets on fire there,

furnishings and equipment, he will have to restore. And with all

free men who have escaped from said fire without their clothes on,

he will have to settle according to their wound money; in the case of

women, however, this will have to be doubled. Moreover, for the

roof of the house, he will have to settle with a fine of 40 shillings.

2. And in the case of the barn[63]

of a free man, if it is enclosed

with walls and provided with a lockable bar, he will have to settle

for the roof with a fine of 12 shillings; if, however, it is unenclosed,

what the Bajuvarians call a scof,[64]

i.e., a shed without any walls, he

will have to settle with a fine of 6 shillings.

In the case of such a granary, however, as they call a parc,[65]

he

will have to settle with a fine of 4 shillings.

But in the case of a mita,[66]

if he un-roofs it or sets it on fire, he

will have to settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

But in the case of a smaller one, which they call a scopar,[67]

he

will have to settle with a payment of 1 shilling.

And everything he will have to restore in like.

3. In the case of smaller buildings, if someone devastates them,

or tears their roofs down, as often happens, or surrenders them to

fire, which they call firstfalli,[68]

he will have to settle for every one

which is separately built, such as a bathhouse, a bakehouse, a

kitchen house, or any other structure of this sort, with a fine of 3

shillings and will have to restore whatever is destroyed or burned

down.

4. However, if he sets fire to a house so that it bursts into flame

yet the house does not burn down and is saved by the members of

the household, he will have to settle the wound money for each of

the free people, because he inunwan[69]

them, as they say, i.e., put

them in fear of their life, and beyond that he will not have to make

any further compensations in excess of that which has been consumed

by the fire.

The fines forfeited to the duke, however, remain unaffected.

And if he wishes to contest any of these he will have to defend

himself with a champion or must take an oath supported by 12

oath helpers.

As far as the serfs are concerned the destruction of a house

(firstfalli) will have to be settled in like manner as the cutting off of

a hand.

5. And now, since we deem our ruling on the burning of buildings

completed, it is not inappropriate that we explore in greater

detail the fines imposed upon the destruction of the living quarters

of a household.

6. If someone with criminal or any other intent, through arrogance

or hostility, through negligence or a certain lack of understanding,

tears down the roof of a free man, he will have to settle

with a fine of 40 shillings.

7. If [he tears down] that post by which the ridge is held in place

and which they call firstsul ("ridge post"), he will have to settle

with a fine of 12 shillings.

8. If he tears down in the interior of the building that post which

they call winchilsul ("corner post"),[70]

he will have to settle with a

fine of 6 shillings.

9. For the other posts of this order, however, he will have to

settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

10. But for the corner posts of the outer order he will have to

settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

11. For all the other posts of this order he will have to settle, for

each individually, with 1 shilling.

12. For the tie beams,[71]

however, he will have to settle each with

a fine of 3 shillings.

13. For the outer beams, however, which we call spanga[72]

[literally,

"clamp"] because they hold together the order of the walls,

he will have to settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

14. For everything else, however, that is the boards,[73]

the

shingles,[74]

and the bracing-struts,[75]

or whatever else is used in the

construction of a building, he will have to settle with 1 shilling each.

And if a person has inflicted all of this damage to the building

of another person, he shall not be compelled to pay more than what

is due for the destruction of the roof and whatever crimes he has

committed greater than this. Minor infractions of this person are

not to be prosecuted with the exception of those for which restitution

has to be made according to law.

The article then goes on to define the compensation set

for damage to the yard, the braided wattle enclosures, the

pastures, roads, and pathways.

Of all surviving literary sources on early medieval architecture

this article of the Lex Bajuvariorum offers the

fullest and most detailed information on the nature of

contemporary domestic building. In the first place it

confirms what had already been demonstrated by the Lex

Alamannorum, namely, the fact that the West Germanic

farmhouse of the eighth century consisted of an aggregate

of separate structures, which included a living house (domus),

a bathhouse (balnearius), a bakehouse (pistoria), and a

kitchen house (coquina), plus an entire group of agricultural

service structures, such as the various barns and stables

(scoria, granarium quod parc appellant, etc.). But more

importantly, in paragraphs 6-14 we are furnished with an

item by item account of the component members of the

roof-supporting frame of timber. Their functions are defined

by their names, listed often both in Latin and in their

vernacular Old High German form; and their varying

size and structural importance are reflected in the weight

of the fine that is placed upon their damage or destruction.

Listed in the sequence of their constructional importance

they are:

1. Culmen or first: the "ridge" or "ridge beam" to

which the head of the rafters is fastened. Its demolition

entails the collapse of the entire roof; hence, the largest

fine is set for its destruction (40 shillings). In the Lex

Bajuvariorum the term is alternatingly used in the specific

sense of "ridge" or "ridge pole" or as pars pro toto for the

entire roof of the house.

2. Firstsul: "the post by which the ridge is carried" (eam

columnam a qua culmen sustentatur). The structural importance

of this column finds recognition in the fact that the fine

imposed upon its demolition is set at 12 shillings, almost a

third of the fine imposed for the destruction of the whole

house.

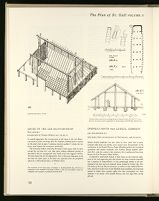

HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM. 8TH CENTURY

287.B

287.A

287.D

287.C

RECONSTRUCTION BY OTTO GRUBER (1926, 24, fig. 13)

The principal characteristic of the house type on which Gruber modeled his reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house is that its roof is supported

by three parallel rows of posts, the center row carrying a ridge beam, the outer rows roof plates or purlins. Gruber calls this a "ground floor house for man

and livestock" (ebenerdiges Wohnstallhaus). The earliest extant examples date from the end of the 15th century. They are found on both the Swiss and

German sides of Lake Constance, the Aargau, the Kanton of Bern in the southern parts of the Black Forest, and less frequently in the Saar river basin

and the Eifel Mountains.

In late and post-medieval times the interior of this house was divided, in accordance with the transverse alignment of its posts, into a series of compartments

used for hay or harvest storage (Schopf), usually under a hipped portion of the roof; for livestock (Stall); as central access area to other compartments

(Tenne) and in winter also for wagon storage; as kitchen (Küch); and as a withdrawal area often subdivided by an axial wall into two private rooms

(Stuben), under the roof at the end of the house opposite the Schopf.

In general structural organization this house may well derive from that of the Lex Bajuvariorum, but whether the latter may have been divided into

compartments cannot be decided on textual evidence. (For extant examples see O. Gruber, 1926, and a posthumous study by him, Bauernhäuser am

Bodensee, edited by K. Gruber, Lindau and Konstanz, 1961.)

3. Winchilsul: this member is explicitly said to stand in

the interior of the building (interioris aedificii). It is part of

a columnar order whose individual posts (assessed at 3

shillings) rate only half of its own value (6 shillings).

The context leaves no doubt that winchilsul was the Old

High German designation for the four corner posts of the

freestanding inner frame of timbers which carried the roof

plates and separated the house internally into a center

space and a peripheral suite of aisles. The corner posts

were obviously of a heavier make than "the remaining

posts of this order" (ceterae huius ordinis), since they were

rated twice their value. But rising only midway up to the

roof, they rate in turn only half the value of the ridge-supporting

firstsul.

4. Columna angularis exterioris ordinis: "the corner

column of the outer order of posts." Its penal value amounts

to 3 shillings, in contradistinction to the "other members

of this order" (aliae columnae huius ordinis) which are

assessed at 1 shilling each.

The relative value assessed to all of these members

suggests that the outer wall posts had only half the strength

of the posts of the inner frame.

5. Trabes: the horizontal long and cross pieces ("tie

beams" and "roof plates"), which frame the principal

uprights together. The relation of paragraph 12 to paragraph

13 leaves no doubt that trabes is used as a generic

designation for all those horizontal timbers which connect

the uprights lengthwise and crosswise. Paragraph 12 deals

with the trabes of the inner order, i.e., the "tie beams"

and "roof plates" which connect the principal inner posts

that separate the nave from the aisles of the hall. Their

penal value (3 shillings) is identical with that of the supports

on which they rest, save for the heavier corner posts

(winchilsul) which rate twice that value. Paragraph 13

deals with the trabes of the outer order (exterioris vero) and

refers to them with the Old High German designation:

6. Spanga, "clamp," so-called "because they hold the

walls together." The fine assessed for the destruction of

these timbers, in modern architectural terminology referred

to as "wall plates," is identical with that of the corresponding

pieces of the inner order (3 shillings).

7. Asseres, laterculi, and axes, the "rafters," the "shingles,"

and the "bracing struts". Their penal value is 1

shilling each.

We are not the first, of course, to try our hand at a

reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house based on

this meticulous enumeration of its component structural

members. A first attempt of this kind, consisting of a plan

only, was made in 1902 by Karl Gustav Stephani (fig.

286);[76]

a second, consisting of a plan and various sections

and elevations, in 1926 by Otto Gruber (fig. 287);[77]

and a

third, in the form of an isometric perspective, in 1951 by

Torsten Gebhard (fig. 288).[78]

Stephani's interpretation (fig. 286) of the house as a one-room

structure with a porch on one of its narrow ends

misses the basic message of the text, which makes a clear

distinction between an "inner" and an "outer order of

posts" and within each of these between their "regular

members" and their "corner posts." This suggests a house

that is composed of a center space and a peripheral belt of

outer spaces. Even more untenable is Stephani's explanation

of firstsul as a ridge-supporting center post. I presume

that it was the fact that this term is used in the singular

which induced Stephani to interpret the passage to mean

that the ridge of the Bajuvarian house was supported by a

single post that stood in the very center of the building.

Such an arrangement is constructively incongruous and

must be refuted on both linguistic and architectural

grounds. Linguistically, one finds, the singular form appears

again in the very next paragraph, and there it refers

to a structural member (winchilsul, "corner post") which

by definition cannot have possibly existed in a singular

form, since a house with one corner post would be a logical

absurdity. Constructionally, a ridge beam may be supported

by a center post, but a center post alone could not

possibly hold it in place; its stability required additional

supports at each end of the beam. It must have been

Stephani's faulty exegesis of the text that induced Dehio

to remark with regard to the Lex Bajuvariorum that "the

attempt to reconstruct the Bajuvarian standard house is

unconvincing."[79]

The criticism is fully justified when

applied to Stephani, but it would be wrong if it implied, as

the context suggests, that the source did not lend itself to a

convincing reconstruction.

Gruber's reconstruction (fig. 287) comes considerably

closer to the truth; but his internal subdivision of the house

into areas used as stables, barns, and living quarters are derived

from post-medieval house forms (Old Upper Suebian

farmhouse and Hotzen house) and are, therefore, purely

conjectural. Decidedly wrong in Gruber's reconstruction

is the application of the term winchilsul to all the members

of the "inner order" (designated with the Arabic figure 2

in his plan), because the text distinguishes clearly between

the "corner posts" (winchilsul) and the "other columns

of this order" (ceterae vero huius ordinis).

By far the most convincing of all the existing reconstructions

is that of Thorsten Gebhard (fig. 288). As a point of

minor criticism it might be noted that there is nothing in

the Lex Bajuvariorum which would suggest that the center

space was boarded off against the outer space by the solid

wooden paneling shown in Gebhard's reconstruction;

while, conversely, this reconstruction fails to show a feature

that is explicitly mentioned in the text, namely, the "remaining

posts of the inner order" (ceterae huius ordinis

[columnae]). Gebhard is probably right when he assumes

that the Bajuvarian standard house had its principal

entrance in the middle of one of its long sides, but again

HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM

288. AXONOMETRIC VIEW

8TH CENTURY

[reconstruction by Thorsten Gebhard, 1951, 234, fig. 3]

In overall appearance this reconstruction of the house of the Lex Bajuvariorum

is fairly convincing. But like Stephani, Gebhard fails to account

for the inner order of posts ("columnae interioris aedificii") which, the text

states, stood between the cornerposts (winchilsul).

The horizontal timbers connecting the heads of these posts could not have

carried the roof load over very wide spans without additional posting as

described in the text; unsupported, they would surely have sagged or broken.

The same holds true for the ridge purlin. Nor is there any indication in the

text that the center space of the house was separated from the peripheral

spaces by a solid wall partition, as Gebhard shows.

The orientation of the large group of buildings at Zwenkau-Harth (fig. 288.X.a) is

conspicuous in the treatment to be found in Quitta, 1958, and was possibly to gain advantageous

solar exposure, or protection from the wind.

ZWENKAU-HARTH NEAR LEIPZIG, GERMANY

288.X.b SECTION

3RD MILLENNIUM B.C.

[after Quitta, Neue Ausgrabungen in Deutchland, 1958, 69 and 75]

Houses divided lengthwise into four aisles by three axial rows of posts,

carrying ridge beam and purlins, were among main characteristics of the

architecture of the Banded Pottery People (Bandkeramiker) who introduced

agriculture and animal husbandry into Central Europe between 50003000

B.C., and who, owing to their sedentary life of seeding and harvesting,

became the first European village builders.

A distinctive construction feature of their houses is the transverse alignment

of the roof-supporting posts that divide the house crosswise internally

into a sequence of compartments—a trait perplexingly similar to the partitioning

of the late and post-medieval houses studied by Gruber (fig. 287).

The house of the Lex Bajuvariorum, as well as its late medieval derivatives,

may have its first roots in this Neolithic house tradition, but the precise

manner in which these concepts might have been transmitted over three

milennia is not known. (For possible Bronze and Iron Age links, see fig.

289.A)

(fig. 289) I have limited myself to showing only those members

which are explicitly mentioned in the Lex. The Lex

does not tell us anything about the position of the hearth,

but the location of the hearth is not in question. In structures

of this type the hearth was always in the middle, or

somewhere else along the axis of the center space, at

maximal distance from the incendiary timbers of the walls

and the roof.

Dehio, then, greatly underrated the importance of the

Lex Bajuvariorum for the history of early medieval house

construction. This code not only lends itself to a structural

reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house, but it does

so with singular explicitness, and from the information thus

obtained we can draw general conclusions that are of

importance for the broader issues of our study. Foremost

among these is the recognition that during the eighth

century a European house type existed with a general

design that closely resembled the North Germanic house of

the Saga period. Like the latter, it is a skeletal timber

structure and is covered by a large pitched roof, whose

rafters converge in a ridge pole.

There are some distinctive differences, to be sure. In the

Saga house, as has been pointed out, the ridge pole was carried

by short king posts (dvergr) that rose from the center of

the cross beams. In the house of the Bajuvarians the ridge

was supported by posts that rose from the ground. The

Saga house was three-aisled like the Germanic all-purpose

house discussed below, pp. 45ff. The house of the Lex

Bajuvariorum is four aisled, bearing striking, yet so far

inexplicable, resemblance to a house type common in

Central Europe in the 3rd millenium B.C. (see caption,

288X).

Professor Stefan Riesenfeld in the School of Law, University of

California, Berkeley, has had the kindness to check this translation for

correctness of its legal terminology.

scoria. Other Old High German versions are: scura, sciura, or

schiure; New High German: Scheuer; French: écurie; cf. Heyse, II,

1849, 667.

scof. Other Old High German versions are: scopf, schopf; Middle

High German: shopf and schopfe; New High German: Schopfen, i.e., a

"weather roof"; cf. Grimm, IX, 1899, col. 153.

parc. Other Old High German versions are: pharrich, pherrich;

Middle and New High German: pferch; from Middle Latin parcus, an

enclosure or shed either for animals, or for the storage of grain or

hay; cf. Grimm, VII, 1889, col. 1673.

mita: from Latin meta; Low German: mite; Dutch: mijte; New

High German: Miete; all in the sense of a haystack or stack of sheaves

protected by a conical roof of thatch which rested on poles and could be

lowered and raised according to need; cf. Grimm, VI, 1885, col. 2177.

A typical example of this type of structure can be seen in the background

of the picture of Ruth and Boas in the Dutch Bible of about 1465,

reproduced in fig. 368.

scopar. Other Old High German versions are sopar, sober; New

High German: Schober; a stack of hay, straw, or grain sheaves piled in

the open field; cf. Heyse, II, 1849, 775.

first: identical with New High German First; Middle High German

virst or fuerst; Anglo-Saxon fierst, first; cf. Grimm, III, 1862, cols.

1677-78.

The verb inunwan does not occur in any of the Old High German

dictionaries and glossaries that are available to me, and Eckhardt leaves

it untranslated. However, from the explanatory apposition that follows

(in disperationem vitae fecerit), one would suspect it to be equivalent with

"exposed them to the danger of losing life and limb."

winchil: identical with New High German Winkel, "angle" or

"corner"; cf. Steinmeyer and Sievers, III, 1895, 128, No. 63 (Angulus

winchel, winkil).

trabes: in classical as well as in Medieval Latin this term is used for

the horizontal cross and long beams, which frame the principal uprights

together, i.e., "tie beams," and the "plates."

spanga: identical with New High German Spange, a "clamp," here

used in the specific sense of "wall plate," the horizontal beams that

frame the wall posts together.

asseres. Since we are obviously not dealing here with primary

structural members, asseres cannot be used here in the sense of "post"

or "pole," but is more likely to stand for "board" or "lath," and may

refer to either the covering material of the walls or the grill of laths on

the roof into which the shingles are keyed.

laterculus: in classical Latin "a small brick"; in Medieval Latin,

however, also used for "shingle," as follows from a passage quoted by

Du Cange: "Turris laterculis ligneis cooperta, id est, scandulis" (V, 1938,

35).

axis: in classical Latin "axle tree"; but also "board" or "plank."

Since in its primary sense this term appears to denote a connecting

piece of timber, I should be inclined to assume that it may be used here

for the smaller subsidiary "struts," which stiffen the main frame of the

building, or for the "collar beams," which brace the rafters.

Gudmundsson's contribution to the architectural history of the

Middle Ages is extraordinary. In assessing its significance one can only

express regret at the limited effect his findings have had upon the study

of medieval house construction. The reasons for this are several. First,

perhaps, is the fact that house research has never been a primary interest

of the architectural historian of the Middle Ages. Second, the fact that

Gudmundsson's work, which was well known, of course, to philologists

and literary historians, was available to architectural historians only

through German summaries (I refer to such works as Dietrichson-Munthe,

1893; and Stephani, I, 1902, 361ff). These lacked Gudmundsson's

own compendious apparatus of references to the originals and

therefore left the reader unable to judge the methods by which these

results were obtained. Third, and even more important, there is no

denying that even for one who is tolerably well acquainted with the

Nordic Sagas, Gudmundsson's book is extremely difficult to absorb.

It is spiked with thousands of references, whose relevance can only be

judged in their original context. The Sagas do not contain at any one

place a full and systematic description of their heroes' dwellings. This

picture rather has to be pieced together from parts that are scattered

throughout a vast array of different sources, and it becomes alive and

convincing only as the fragments grow together into a coherent whole.

Until very recently few of these sources had been translated into modern

languages. Many of them, even today, are available only in their Old

Norse editions. A proper evaluation of Gudmundsson's methods, for this

reason, requires not only a considerable fluency in the Old Norse

language, but also an extremely bulky apparatus of early editions.

The material that follows was written before the publication of

Dölling, 1958. I am pleased to find that there is no need to modify any

of my findings in the light of Miss Dölling's valuable study, which deals

with a considerably wider range of sources than are here adduced.

CAROLINGIAN CROWN ESTATES AND THEIR

HOUSES, IN THE LIGHT OF

CONTEMPORARY ADMINISTRATIVE ORDINANCES

AND PROPERTY DESCRIPTIONS

In contradistinction to the Alammanic and Bajuvarian law,

the law of the Franks (Lex Salica)[80]

is a disappointingly

unrewarding source of architectural information. It does

not include a special chapter on arson, nor does it otherwise

define the fines imposed upon the demolition of the whole

or any part of the Frankish house. But this deficiency is

compensated for, to some extent, by the survival of two

administrative ordinances of the Frankish court which give

us some insight into the architectural layout of a royal

crown estate, the Capitulare de villis and the so-called

Brevium exempla.

CAPITULARE DE VILLIS

The Capitulare de villis,[81]

an ordinance formerly assumed

to have been drawn up in 794 or 795 by the young Louis

the Pious in order to correct certain abuses that had

arisen in the administration of the royal estates of Aquitania,

is now believed to have been issued by Charlemagne

shortly before 800 as a directive to the entire empire

(except Italy) in part to curtail mismanagement, in part to

set a program for the future. Among the seventy-odd

articles of which it is comprised, there are some that refer

to architecture. They read like a description of some of the

guest and service structures of the Plan of St. Gall, and

exhibit with vivid distinctness the basic similarity of the

architectural layout of a secular and a monastic Carolingian

manor. In fact, being laid down for the specific purpose of

defining what buildings are considered to be indispensable

components of a royal estate, they form literary counterparts

to the agricultural service structures of the Plan of

St. Gall. While providing us with a comprehensive picture

of the diversity of buildings associated with Carolingian

crown estates, they unfortunately do not tell us anything

about their design or construction.

I am extracting from these articles whatever appears to

have a bearing on architecture, without regard to the order

in which this material appears in the original.

Article 27 prescribes: "At all times our houses [casae

nostrae] shall be provided with fireplaces and fire[?]guards

[foca et wactas habeant] so that they do not suffer any

damage."[82]

Article 42 specifies the household equipment of the

royal supply room (camera). It stipulates that it be provided

at all times with its full complement of bedding,

tableware, cutlery, cooking equipment, and all other kind

of utensils, so that one will never be in need of sending for

them or borrowing them from outside. It contains nothing

further that would shed any light on the layout of the

royal mansion itself.[83]

Article 41 provides, "that the buildings in our estates

[intra curtes nostras], and the surrounding fences [sepes] be

well guarded and that the stables [stabulae], the kitchens

[coquinae], the bakehouse [pistrina], and the presses [torcularia]

be planned with care, so that our men [ministeriales

nostri] can perform their functions properly and with

cleanliness."[84]

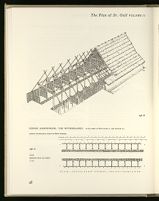

289.A HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM. 8TH CENTURY

PERSPECTIVE WITH ROOFING REMOVED, SHOWING STRUCTURAL SCHEME

AUTHOR'S INTERPRETATION

The relative severity of the penalties imposed by the Lex Bajuvariorum to compensate a householder for willful damage done to his dwelling

(see fig. 289.B) is clearly related to the size and structural importance of the particular timber involved. The preoccupation of the text with

penalties for "pulling down" house timbers presumes that in general the overall framework of the typical house was sufficiently light, and its

key timbers sufficiently accessible, to make this mode of revenge an attractive nuisance.

Timbered early medieval houses with a central row of posts supporting the ridge parlins have, since this chapter was written, appeared in

excavations in Manching and Kirchheim, near Munich (see Schubert, Germania, L (1972), 110ff, and Dannheimer, IBID., L1 (1973), 168ff.

For sporadic Bronze and Iron Age antecedents see Zippelius, 1953, 19, fig. 2; Reinerth, I, 1940, 16, fig. 4b; Pl. 6 opposite p. 26; 28, fig. 7;

139, figs. 60-62; 198, fig. 85.)

I am not aware of the existence of any Central European Bronze and Iron Age houses with three parallel rows of roof-supporting posts. The

connection of the house of the Lex Bajuvariorum with those of the Banded Pottery People suggested in fig. 289.X must therefore be treated

with caution.

In West and North Germanic territory, houses with a row of center posts for carrying ridge purlins are a great rarity. Notable exceptions are

the two Iron Age houses of Wijchen, shown below, figs. 300 and 301.

289.B HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM. 8TH CENTURY

PLAN. STRUCTURAL MEMBERS IDENTIFIED, WITH FINES LEVIED TO COMPENSATE DAMAGE

AUTHOR'S INTERPRETATION

Article 23 prescribes: "Our superintendents shall see to

it that each of our estates be provided with its dairy

[vaccaritia], its piggery [porcaritia], its facilities for raising

sheep [berbicaritia], its facilities for raising goats [capraritias],

and its facilities for raising billy goats [hircaritias];

and of all this they shall have as much as they can handle;

and none of our estates shall be without these installations."[85]

Article 46 prescribes, "that the enclosures for animals

commonly referred to as brogli lucos nostros, quos vulgus

brogilos vocat be well guarded, and always kept in good

repair, and that one should not wait until it is necessary to

rebuild them anew; and the same applies to all of the buildings."[86]

Article 50 prescribes, that each superintendent determine

the number of chickens that should be kept in each stable

(stabulo) and the number of caretakers to be stationed with

them. (In Article 19 it had already been established "that

not less than 100 chickens and 30 geese shall be kept in the

barns of our main estates [ad scuras nostras in villis capitaneis]

and not less than 50 chickens and 12 chickens and

12 geese in our outlying settlements [ad mansioles].")[87]

Article 45 prescribes, "that each of our superintendents

see to it that he have skillful craftsmen [artifices] in his

district [in suo ministerio], that is: blacksmiths [fabros ferrarios],

goldsmiths [aurifices], silversmiths [argentarios], shoemakers

[sutores], lathe workers [tornatores], carpenters [carpentarios],

shieldmakers [scutarios], fishermen [piscatores],

KÄNNE (STAVGARD), PARISH OF BURS, GOTLAND,

SWEDEN

GERMANIC LONGHOUSE, 3RD-5TH CENTURY

PLAN [after Stenberger, II, 1955, iii, fig. 357]

The house was built in two stages. Its northern half (the original dwelling) had

a floor of stamped clay. The inner walls were lined with heavy granite boulders.

The roof was covered with turves that fell into the house as its supporting

timber frame collapsed, smothering the fire that destroyed it.

The floor of the southern half of the house was paved with fine gravel. Its roof

was of lighter construction and its walls less solidly built than the northern half.

Entrances were in the gable walls.

brewers [siceratores], that is, those who know how to

make beer [cerevisam], apple cider [pomatium], pear cider

[piratium], and any other kind of drink; the bakers [pistores],

who make pastry for our table, the netmakers

[retiatores] who know the art of making nets for the hunt,

as well as for fishing and for the catching of birds; and all

such other craftsmen [reliquos ministeriales] which it would

be too long to enumerate."[88]

The best edition of the Capitulare de villis, with excellent commentary

to the Latin terminology, is that of Karl Gareis, 1895. A

complete translation of the capitulary into French will be found in the

earlier edition by Guérard, 1853. The most penetrating commentary on

the date and territorial application of the Capitulare will be found in

Bloch, 1926; Verhein, 1954, and 1955; and Metz, "Das Problem . . . ,"

1954, and 1960, passim.

Gareis, 1895, 40-41. I wonder whether foca et wactas might refer

to hooded and chimney-surmounted corner fireplaces of the kind found

in the bedrooms of the House for Distinguished Guests on the Plan of

St. Gall, as well as in the Abbott's House and the withdrawing rooms of

most of the high-ranking monastic officials; cf. below, p. 123ff.

BREVIUM EXEMPLA

The Brevium exempla ad describendas res ecclesiasticas et

fiscules consist of three specimen descriptions of property,

more or less fiscal in character, and were presumably

drawn up for the guidance of the royal agents who assessed

the produce of the domain.[89]

The first description is of the

possessions of the see of Augsburg on an island in Staffelsee

in Bavaria, the second is part of a register of the possessions

of the Abbey of Weissenburg in Alsace, and the third is

the survey of five royal fiscs directly belonging to the crown.

Two of these are listed by name, viz., the estates of

Asnapium (Anappes in France, dép. Nord, arr. Lille,

cant. Lannoy), and the estate of Treola (no longer identifiable,

probably in Alamannia); three others are left anonymous

(perhaps the hamlets of Vitry, Cysoing, and the

Soumain near Anappes). The date of the Brevium exempla

is uncertain, but the prevailing view is that they were

written about 812.

Considerably less interesting from a general historical

point of view than the Capitulare de villis, the Brevium

exempla have the virtue of being more detailed and factual

in their reference to architectural conditions. Here we are

given a precise account not only of the number and type of

buildings found on each of the five aforementioned

estates, but also of the construction materials, and in the

case of the royal mansions, even the number and type of

rooms. The following passages from the Brevium exempla

describe portions of the crown estates of Anappes and its

outlying settlements, Treola, and three holdings ("anonymous

estates") not cited by name.

The crown estate of Anappes and its outlying

settlements

Invenimus in Asnapio fisco dominico salam regalem ex lapide factam

optime, cameras III; solariis totam casam circumdatam, cum pisilibus

XI; infra cellarium I; porticus II, alias casas infra curtem ex ligno

factas XVII cum totidem cameris et ceteris appendiciis bene compositis;

stabolum I, coquinam I, pistrinum I, spicaria II, scuras III. Curtem

tunimo strenue munitam, cum porta lapidea, et desuper solarium ad

dispensandum. Curticulam silimiter tunimo interclausam, ordinabiliter

dispositam, diversique generis plantatum arborum.[90]

LOJSTA, GOTLAND, SWEDEN

291.C

291.B

291.A

GERMANIC HOUSE

3RD-5TH CENTURY

RECONSTRUCTION BY G. BOETHIUS

AND J. NIHLEN

[photos: Statens Historiska Museet, Stockholm]

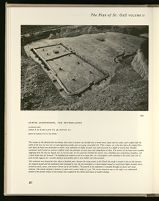

A. Foundation of house after excavation.

A magnificent and one of the first excavated

examples of an aisled Germanic house of the

Migration Period. Its walls were made of

earth carefully lined with stones. The roof

was supported by two rows of wooden posts

rising from flat stones all of which were still

in place. These supports must have been

framed at their heads into stable trusses by

means of cross beams and long beams. The

entrance was in the western gable wall; the

hearth in the middle of the center floor

toward the inner end of the hall.

B and C. Reconstruction of the dwelling.

Reconstructed at full scale on the original

site in 1932, the dwelling follows drawings

submitted by the excavators. Although now

questioned in the rendering of certain

details, this reconstruction nevertheless

gives a very accurate impression of the

unitary quality of the interior space

unmarred by the fact that its roof-supporting

frame divides into a multiplicity

of bays. The roof may not have been

covered with thatch but with turves. The

walls were originally a little higher, and

the entrance wall was probably not straight

but hipped at the eastern end of the roof.

292.A ÞÓRSÁRDALUR VALLEY, ICELAND. HALL STÖNG

PLAN OF HOUSE [after A. Roussel in Stenberger, 1943, 78, fig. 137]

I. Fore room, Jorskáli

II. Sleeping house, skáli, divided by transverse partition into room for men,

karlskáli, and room for women, kvennaskáli

III. Living house, stofa

IV. Dairy, mjólkrbûr

V. Room for cold storage, kjátlari

The house had only one entrance and no windows; it received light and air through a lantern-surmounted opening in the roof. Its turf walls were raised on a stone

foundation two courses high; the roof likewise was covered with turves. The center floor of the main house (II) was of stamped clay and contained a fireplace. Two rows

of posts divided this space into three aisles, the two side aisles being raised and boarded, and partitioned transversely into men's and women's sleeping quarters. A

square area boarded off at the inner end of the south aisle probably formed a sleeping alcove for the farmer and his wife.

The living room (III) contained a hearth for cooking, a stone box 50cm deep. The dairy (IV) was accessible only from inside the house and contained three round

impressions in the floor, presumably from large vats. Its walls were lined with lava stones to a height of 1.1m. A room presumably for cold storage (V) was accessible

only from the fore room (I).

The photograph (fig. 292.B) taken from the door of the living room shows the excavation of the main hall, and reveals with great clarity how the aisles and floor of

the fore room were raised above the level of the center floor. The banked earth of these side aisles was retained by staked boards. Large flat stones at 2-meter intervals

provided footing for the roof posts. Smaller stones set along the walls, pieces of wood still attached, show the house was wainscotted. Absence of personal effects indicates

the residents were forewarned of the eruption of Mt. Hekla, in 1300, that destroyed the house and converted the fertile valley into a wasteland of lava and ash.

The reconstruction (fig. 291.C) portrays the ingenious simplicity with which man could, in a harsh Atlantic climate, make a dwelling not only secure against attack, but

warm and homely as well. The compact top-growth of Iceland terrain is well suited to turf-cutting. For timber the chieftains of the Saga Period relied on wood

imported from Norway, or on driftwood swept in by Atlantic storms from distant North American coasts. The only locally available building material was a dwarf

birch whose fine branches were used as matting for the roof turves.

292.C INTERIOR VIEW OF HOUSE. REDRAWN FROM ROUSSEL, 1943, 211, fig. 144

292.B FOUNDATIONS OF HALL AFTER EXCAVATION. PHOTO COURTESY OF A. ROUSSEL

293. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

FOUNDATIONS,

HOUSE A OF WARF-LAYER VI, 4th CENTURY B.C.

[photo by courtesy of A. E. Van Giffen]

The remains of this flatland-level farmhouse show that its interior was divided into a broad center space and two aisles, each roughly half the

width of the nave, by two rows of roof-supporting wooden posts of young, unscantled oak. Their stumps, cut a few feet above the original floor

level when the house was dismantled to make a new settlement on higher ground, were well preserved to a depth of several feet. Braided

wattlework walls formed an enclosure slightly inside the perimeter of outer posts and independent of them. The corners of the house were rounded,

suggesting that the roof was hipped over its narrow ends. A cross partition divided the interior into a dwelling area containing a fireplace, and

a much larger byre for livestock. The building was entered on one of its long sides. In a rectangular yard extending to the north, nine rows of

posts formed supports for a wooden platform presumably used to store fodder and other produce.

This settlement was dismantled after about a hundred years, because the rising waters of the North Sea made it unsafe to live on this horizon.

As centuries passed and the inundation level continued to rise, the site developed as a dome-shaped mound on successively higher, broader levels,

formed by earth, turves, and manure thrown up by the dwellers. The growth of the settlement is traceable through six layers over seven

centuries. The mound attained a diameter of 450m and a center height of 5.5m. The terrain elevation seen at the right is an undisturbed

portion of the present surface of the mound, now occupied by the church and houses of modern Ezinge.

We found on the royal estate of Anappes the royal hall built in

stone, in the best manner, three chambers, the entire house surrounded

by solaria; with eleven heatable rooms[91]

and below one cellar;

two porches; seventeen other houses within the main yard,[92]

built

in timber, with the same number of chambers, and other appendices,

all well constructed; one stable, one kitchen, one bakehouse, two

grain barns, three other barns. The main yard well protected with

a fence,[93]

with a masonry gate, and above this, a solarium. The

smaller yard likewise enclosed with a fence built in the usual

fashion and planted with various types of trees.

The document subsequently lists the dead and live stock

at Anappes down to the smallest detail, and then turns to

the inventory of the outlying settlements:

In Grisione villa invenimus mansioniles dominicatas, ubi habet scuras

III et curtem sepe circumdatam. . . .

In alia villa repperimus mansioniles dominicatas et curtem sepe

munitam, et infra scuras III. . . .

In villa illa mansioniles dominicatas. Habet scuras II, spicarium I,

ortum I, curtem sepe bene munitam.

In the estate of Gruson[94]

we came upon the outlying settlements.

There are three barns, and the yard is surrounded by a fence. . . .

On another estate we found the outlying settlements and the

yard protected with a fence, and inside three barns. . . .

On a third estate [literally, on "that estate"] we found the

outlying settlement to be comprised of two barns, one granary, one

garden and the yard well protected with a fence. . . .

Curtis, from classical Latin cohors ("enclosure"), in medieval Latin

has a variety of different though closely related meanings. It may designate

a) "a fence"; b) "a fenced-in space containing the house and yard";

c) "a garden or farmyard adjoining the house"; d) "a manor" or

"manorial estate" e) "a landholder's homestead"; f) "the central manor

of a royal fisc"; g) "the place or household of such a fisc"; h) "the body

of persons attendant to a royal household"; i) "the manorial law court"

(For sources see Niermeyer, Med. Lat. Lex, 295-96). In the passages

here quoted we have translated curtis simply as "yard" or where a distinction

is made between curtis and curticula with "main yard" and

"smaller yard".

Tuninum: appears to be a Latinization of Old High German zûn or

tûn. It stands either for "fence" or "a space enclosed by a fence". For

sources see Niermeyer, op. cit., 1048; Du Cange, VIII, 1938, 209; and

Grimm, XV, 1913, 406. Adalhard of Corbie uses it in the sense of

"poultry-yard"; see III, Appendix II, p. 116.

For the identification of Grisione with Gruson, a village 3.7 miles

from Anappes, see Dopsch, 1916, 56.

The crown estate of Treola

Invenimus in Treola fisco dominico casam dominicatem ex lapide optime

factam cameras II cum totidem caminatis, porticum I, cellarium I, torcolarium

I, mansiones virorum ex ligno factas III, solarium cum pisile

I; alia tecta ex maceria III, spicarium I, scuras II, curtem muro

circumdatam cum porta ex lapide facta. . . .[95]

We found on the crown estate of Treola the royal mansion built

excellently in stone, two chambers with the same number of heatable

rooms, one porch, one cellar, one press-shed, three houses for

men, built in timber, a solar with one heatable room, three other

houses [literally, "roofs"] in masonry, one granary, two barns,

the yard surrounded with a wall and [provided] with a stone-built

gate. . . .

The first anonymous estate

Repperimus in illo fisco dominico domum regalem, exterius ex lapide et

interius ex ligno bene constructam; cameras II, solaria II. Alias casas,

infra curtem ex ligno factas VIII: pisile cum camera I, ordinabiliter

constructum; stabolum I. Coquina et pistrinum in unum tenentur.

Spicaria quinque, granecas III. Curtem tunimo circumdatam, desuperque

spinis munitam cum porta lignea. Habet desuper solarium. Curticulam

similiter tunimo interclusam. . . .[96]

We found on that crown estate the royal house, externally built in

stone and inside well constructed in timber; two chambers, two

solars. Within the main yard eight other houses built in timber; a

heatable room with one chamber built in the usual fashion, one

stable. Kitchen and bakehouse built together, five grain barns,

three granaries. The court surrounded with a fence, above provided

with spines, with a wooden gate. It has above a solar. The smaller

yard likewise enclosed by a fence. . . .

294. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

PLAN [after Van Giffen, 1936, Beilage I, fig. 5]

HOUSE A OF WARF LAYER VI, 4th CENTURY B.C.

Plan of the house and storage platform, the remains of which are

shown in the preceding figure. The excavated area is identical with

that shown in figure 296, which shows the next stage of the

settlement.

295. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

EXTERIOR VIEW OF SETTLEMENT, 4th CENTURY B.C.

[redrawn from reconstruction by H. Reinerth, 1940, 88, fig. 25]

The discovery of this Iron Age village in 1931-34 was a great landmark in the history of premedieval house construction in transalpine Europe.

The find showed that a house well portrayed by Albrecht Dürer (fig. 335) and Peter Bruegel the Elder (fig. 336) was already fully developed

and in common use for close to 2,000 years.

Later excavations brought the even more startling discovery that this same house type was a standard construction form as early as 1250 B.C.,

and perhaps even in the 14th century B.C. (fig. 323). In the lowlands of Holland and Northern Germany, the same house is used even today

with only minor modifications, for the same purposes for which it was originally conceived (Frisian Los-hus, Lower Saxon Wohnstallhaus).

Its life span is at least 3,300 years, and does not yet appear to have entered its terminal phase.

The most distinctive trait of this type of structure is that it offers, with only a minimum of materials, an ingeniously simple method of covering

large spaces beneath a vast roof carried by a frame of light timbers; these divide the interior of the house lengthwise into nave and two aisles

(figs. 297, 298) and crosswise into a multitude of separable yet transparent bays.

The building type owes its longevity to its ability simultaneously to offer spatial

unity and spatial divisibility. In pre- and protohistorical times almost exclusively

confined to dwelling, sheltering of animals, and harvest storage, the structure entered,

in response to growing complexities of medieval life and social organization, a

virtually explosive phase of functional variety, and came to fill many diverse needs.

On the highest of society, it appeared as residential and administrative seat for

feudal lords and their retainers (figs. 339, 340, and 344-348), including the king

himself. It was used as church (Horn, 1958, 4, figs. 3-8) and Horn, 1962); as

hospital for the sick and infirm (figs. 341-343); as meeting and council hall for the

guilds. And from the 12th century onward in response to the rise of international

trade it became, in Paris and countless smaller towns of France, the standard form

for urban market halls, under whose sheltering roofs the local peasants and traders

from distant places could rent stalls from which to sell produce and goods (Horn

1958, 15ff; Horn and Born, 1961, Horn, 1963).

The second anonymous estate

Invenimus in illo fisco dominico casam regalem cum cameris II totidemque

caminatis, cellarium I, porticus II, curticulam interclusam

cum tunimo strenue munitam; infra cameras II, cum totidem pisilibus,

mansiones feminarum III, capellam ex lapide bene constructam; alias

intra curtem casas ligneas II, spicaria IV, horrea II, stabolum I,

coquinam I, pistrinum I; curtem sepe munitam cum portis ligneis II et

desuper solaria.[97]

We found on that crown estate the royal house with two chambers

and the same number of heatable rooms, one cellar, two porches,

the smaller yard enclosed by a well-built fence; inside, two chambers

with the same number of heatable rooms, three houses for women,

a chapel well constructed in stone, two other timber houses in the

court, four grain barns, two hay barns, one stable, one kitchen, one

bakehouse. The main yard protected with a fence with two wooden

gates and solaria above.

The third anonymous estate

Repperimus in illo fisco dominico domum regalem ex ligno ordinabiliter

constructam, cameram I, cellarium I, stabolum I, mansiones III,

spicaria II, coqinam I, pistrinum I, scuras III, Curtem tunimo circumdatam

et desuper sepe munita. . . Portas ligneas II. . . .[98]

We found in that crown estate the royal house constructed in timber

in the usual fashion, one chamber, one cellar, one stable, three

dwellings, two grain barns, one kitchen, one bakehouse, three

barns. The yard surrounded with a wall, protected above by a

fence . . . two wooden gates. . . .

While failing to reveal anything about the architectural PLAN, CLUSTER SETTLEMENT, Warf-layer V, 4th-3rd cent. B.C. [after Van Giffen, 1936, Beilage I, fig. 4] In the center: the main house, its axis running from west to east.

design of the enumerated structures, the Brevium exempla

are of particular value because they offer concrete information

about the relative use of stone and timber in the architecture

of a Carolingian crown estate. The account of the

sala regalis at Anappes—as we had occasion to point out in

an earlier chapter—[99]

with its open solariums, heatable

rooms, and two galleried porches reads like a description

of the Abbot's House on the Plan of St. Gall. Like the

latter, it was composed of several stories and built in

stone. The Brevium exempla, however, make it equally

clear that stone was not considered to be the ordinary

material. With the exception of the chapel of the second

anonymous estate and the two gate houses at Anappes and

Treola, stone appears to be the exclusive prerogative of the

royal mansion, and the superlative form of the epithets

associated with the use of this material (ex lapdie optime

factam) is indicative of the high esteem in which this

material was held. However, only two out of five royal

mansions recorded in the document were entirely stone

structures, those of Anappes and Treola. The domus regalis

of the first anonymous estate had its outer walls constructed

in stone, but everything else inside is in timber (exterius

ex lapide et interius ex ligno bene constructam.) The domus

regalis of the third anonymous estate was built entirely in

wood (ex ligno ordinabiliter constructam). Timber, we will

also have to assume, was used where no specific reference

to any material is made for the casa regalis of the second

anonymous estate. All the other structures of the five

estates either are explicitly said to be built in timber or

296. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

The first three bays of each aisle are cross partitioned and served as

stalls for cattle. To the south (placed at right angles): three smaller

houses of the same construction, two of these used as dwellings; the

third, like the main house, for both cattle and men. For a larger

plan of the latter, see fig. 327.

absence of any statement to the contrary. And the timbered

buildings formed, of course, an overwhelming majority.

Best edition is that of A. Boretius, in Mon. Germ. Hist., Leg. II,