The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| VI. | VI |

| VI. 1. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

VI

THE PLAN OF ST. GALL

& ITS EFFECT ON LATHER

MONASTIC PLANNING

TRADITION AND CHANGE

by CAROLYN MARINO MALONE and WALTER HORN

INTRODUCTION

THE sections that follow deal in a tentative form with the effect that the ideas embodied in the Plan of St. Gall

had upon later monastic planning. An exhaustive treatment of such effects would require a separate book; nevertheless

we will attempt to illuminate the question by concentrating on a selected group of later monasteries and by

discussing only certain basic aspects of a far larger and more subtle complex of problems. Foremost in consideration

are three questions that have always been of concern to the historian of monastic planning:

1. To what extent did Abbot Gozbert and his successors adhere to the Plan when they rebuilt the monastery

of St. Gall from 830 onwards?2. Did the concepts embodied in the Plan establish a tradition?

3. If this was the case, to what extent was this tradition modified by innovations deriving from new customs

in the Cluniac, autonomous Benedictine, and Cistercian monasteries of the eleventh and twelfth centuries?

FOR the treatment of the first of these three questions I am responsible. The examination of the two others,

discussed in chapters 2 through 5, is based on a master's thesis written by Carolyn Malone and completed in

time to allow its results to be included in this book. The research embodied in these chapters and its presentation

are hers. I have made some minor additions, including all of the extended figure captions. We conclude with a

brief Epilogue, and a review of excavations beneath Gozbert's church, based on a report by architect Dr. H. R.

Sennhauer, in charge of excavations.

W. H.

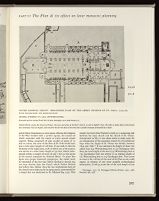

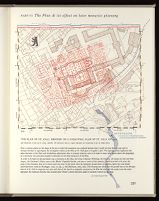

506.A ST. GALL SITE OF THE FORMER MONASTERY WITH ITS PRESENT BUILDINGS

AIR VIEW FROM NORTHWEST LOOKING SOUTHEAST

The Carolingian church and virtually all other monastic buildings were completely rebuilt between 1755 and 1767/68, but the street pattern

and alignment of houses clustering around the church even today reflect, with amazing accuracy, the boundaries of the original monastery site.

The Baroque church is co-axial with the three preceding medieval churches (see fig. 513.A-B) and almost identical with them in width and

overall length. Double-apsed like the church of the Plan of St. Gall, it is, like the latter, without façade. By contrast its towers, flanking the

apse at the eastern end of the building, do not guard the western entrances to the church, but rather signal to the outside world the location of

the high altar and the relics of St. Gall.

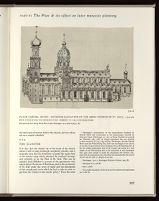

506.B ST. GALL. SITE OF THE FORMER MONASTERY WITH ITS PRESENT BUILDINGS

AIR VIEW FROM SOUTHEAST LOOKING NORTHWEST

The primary reason for construction of the present church owed to the sack of the monastery in 1712 by the Protestant citizenry of Zürich and

Bern. The reconstruction was undertaken with palatial magnificence, and a breathtaking aesthetic exuberance that derived its vitality from a

new alliance of the landed aristocracy of Europe with Catholicism.

In the wake of this accord spread one of the most lavish architectural styles of all ages. The designers of the new church endeavored to reconcile

the directionalism of the traditional western church with a concept of centrality by arresting its longitudinal flow midway in the swirl of a

domed rotunda, and by merging nave and aisles into a single undulating body of space.

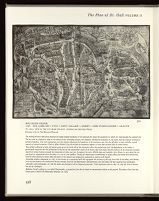

507. MELCHIOR FRANK.

1596 DIE LOBLICH * STAT * SANT GALLEN * SAMBT * DEM FURSTLICHEN * CLOSTR

ST. GALL, VIEW OF THE CITY FROM THE EAST. ETCHING ON IRON (40 × 61cm)

[Courtesy of the St. Gall Historical Museum]

The etching portrays with great precision the wedge-shaped boundaries of the elevated site (lower left quadrant) on which St. Gall founded his original cell.

The site owed its distinctive shape to the courses of two converging streams, the Steinach, skirting the monastery to the south, and the Irabach, forming its

northern boundary. The river escarpments not only sharply delineated the boundaries of the monastery site, but also afforded, at least initially, a good

measure of natural protection. Even in Abbot Gozbert's day (816-836) the monastery appears to have been enclosed only by wattle fences.

The earliest settlement of serfs and tenants grew up on the north side of the monastery where the ground was level. Its dependence on the abbey is

permanently engraved into the architecture of the city by the semicircular course of its streets, that even today hug the contours of the monastery grounds.

Search for urban freedom strained the relationship of abbey and city throughout the entire Middle Ages and reached a first climax in 1475 when the city

purchased its independence from the abbey at a cost of 7000 guilders. During the Reformation (commencing in 1524), abbot and monks were forced into

exile but were allowed to return when the power of the citizens was temporarily weakened by warfare with Kapel.

Increasing conflicts culminated, in 1567, in the erection of a separation wall that segregated the territory of the city from that of the abbey, and thereby

froze into permanency the confessional division brought about by the Reformation. Henceforward, city and abbey led their separate lives politically,

culturally, and economically. In 1798 the abbey was divested of all its temporal possessions. Total supression came in 1805. In 1847 the church became

the seat of a bishopric.

Melchior Frank's etching is a so-called Planprospekt, a perspective from the air based on measurements taken on the ground. The plate is lost; the only

known print is held in the Historiches Museum, St. Gall.

VI. 1

REBUILDING OF THE

MONASTERY OF ST. GALL BY

ABBOT GOZBERT & HIS

SUCCESSORS

FROM A.D. 830 ONWARD

VI.I.I

HARDEGGER'S CONTRIBUTION

Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, the church

which Abbot Gozbert built between 830 and 837 was still

essentially intact, except for its transept and choir. From

1755 onwards, however, not only the church itself but

most of the conventual buildings as well were torn

down to make room for the magnificent and stately rococo

buildings that form the pride of modern St. Gall (figs. 505

and 506). The street pattern and the alignment of the

houses that cluster around the abbey retain with astonishing

precision the shape of the original site, but of the Carolingian

buildings that once rose on this precinct not a single

stone appears to be left above ground level. A satisfactory

answer to the question of whether, or to what extent,

Abbot Gozbert and his successors adhered to the Plan of

St. Gall as they rebuilt the monastery could only be found

through a systematic program of excavations, for which at

present there does not appear to exist a glimmer of hope.[1]

If we are nevertheless not entirely ignorant about Gozbert's

work, this is due to the existence of a precious set of

architectural drawings made early in the eighteenth century

when much of the Carolingian work was still discernible.

These late drawings have been brilliantly analyzed by

August Hardegger, first in a dissertation published in

1917,[2]

and a few years later in a volume of the Baudenkmäler

der Stadt St. Gallen, which Hardegger wrote in

cooperation with architect Salomon Schlatter and Traugott

Schiess.[3]

It is to the imaginative, yet sober and cautious

reasoning displayed in these studies, that we owe whatever

tangible knowledge can be gleaned from the available

sources about the design and layout of the monastery

rebuilt by Abbot Gozbert and his successors.

For a peremptory review of excavations undertaken in 1964 in

connection with the installation of a new heating system in the 18thcentury

church see Sennhauser, 1965. A full report by Sennhauser on

these findings is pending.

VI.1.2

THE CHURCH

The dedicatory inscription of the Plan and the general

historical context in which it was made leave no doubt that

the Plan was drawn upon the request of Abbot Gozbert

(816-836) of St. Gall for the purpose of giving him guidance

in rebuilding his monastery.[4]

Gozbert began this

project in 830 by demolishing the church which Abbot

Otmar had built toward the middle of the preceding

century.[5]

The work on the new church proceeded so

rapidly that it could be dedicated in 837.[6]

Gozbert's church was gutted by fires in 937, 1314, and

1418 but the bulk of the walls, the clerestories of the nave

and their supporting arcades apparently were not signally

affected by these events.[7]

By contrast, the transept and the

choir were completely rebuilt by the Abbots Eglolf and

Ulrich VIII, from 1439-83.[8]

It is in the form it had then

attained that the church is portrayed on the oldest bird's-eye

views of the city: in a woodcut dated 1545 by Heinrich

Vogtherr, in an etching on iron by Melchior Frank, dated

1596 (fig. 507), in an engraving of essentially the same

view by Matthaeus Merian, published in 1638 (fig. 509X),

as well as in several other drawings, the most important of

which are a pen drawing of 1666 and a large drawing on

parchment of 1671.[9]

In 1712 the abbey was ransacked by the Protestants and

the monks were expelled.[10]

When they returned a few

years later it was painfully clear that extensive restorations

would have to be undertaken. In anticipation of that event

some detailed architectural surveys were made. In 1717

architect Johannes Caspar Glattburger surveyed the church

and recorded its dimensions.[11]

Two years later Pater Gabriel

Hecht made a scale-drawn plan of the entire monastery

site, dated September 17, 1719 (fig. 510). In 1725-26 he

added to this a set of no less than fourteen architectural

drawings, in which he set forth how he thought the damaged

church and other monastic buildings should be renovated.[12]

508. ST. GALL. ABBEY AS IT APPEARED ABOUT 1642. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW FROM THE EAST

DETAIL OF A MODEL OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL

ST. GALL, HISTORISCHES MUSEUM [photo: Horn]

render the condition of the still surviving parts of the

medieval church with great precision and show that what

Hecht had in mind was not so much a reconstruction as a

superficial modernization of the then existing work. Hecht

proposed that the gothic choir be retained in its entirety.

He added some baroque touches in surface treatment by

superimposing a new columnar order upon the exterior

elevation of the choir. In the interior he modernized the

Gothic supports but otherwise retained the structure as he

found it, leaving its Gothic vaults and windows wholly

untouched. In the nave, likewise, he does not appear to

have undertaken any radical changes. Hardegger is convinced

that the arcades and the superincumbent clerestories

of the nave which Hecht had before his eyes as he made his

drawings were in essence still those of Abbot Gozbert's

church (compare fig. 511A and B with fig. 512B and C).

He feels that Hecht proposed to retain the intercolumniation

of Gozbert's church and confined himself to simply

increasing the heights in this part of the building. The only

truly new feature in his proposal was the conversion of the

two nave bays lying next to the choir into a pseudotransept

surmounted by a dome, and the introduction on each of

the two long sides of the church of a continuous system of

chapels. For the rest he confined himself to superimposing

upon the existing work a decorative relief of surface

features, designed in the prevailing taste of the period.

This included in the the interior the complete encasing of

Gozbert's arcade columns in baroque shaped piers.

Although Hecht's design proposals had no effect on the

actual course of events, which took a radical turn a quarter

of a century later, they are of incomparable historical

value because they embody with amazing accuracy the

record of what was then still left, or could then be discerned,

of Gozbert's church. In analyzing this material, Hardegger

came to the following conclusions concerning Gozbert's

church and its relation to the Plan of St. Gall:

1. As stipulated in the explanatory legends of the Plan

of St. Gall, Abbot Gozbert assigned to the nave of his

church a width of 40 feet and to each of his aisles a width

of 20 feet—dimensions which also are in conformity with

the manner in which the Church is drawn on the Plan.

2. In full compliance with the intercolumnar titles of

the Plan, but in deviation from the drawing (in which the

509. ST. GALL. ABBEY AS IT APPEARED ABOUT 1642. BIRD'S EYE VIEW FROM THE SOUTHEAST

DETAIL OF A MODEL OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL

ST. GALL HISTORISCHES MUSEUM [photo: Horn]

arcades an intercolumnar span of 12 feet.

3. In full compliance with the great axial title of the

Church of the Plan, but again in deviation from the

drawing (where the church is shown to have a length of

more than 300 feet) he reduced the length of the church to

200 feet. He attained this goal by drastic changes in the

design of the nave of the church, but retained the layout of

transept and choir virtually in the form in which it was

shown on the Plan.

Hardegger's supporting evidence for these conclusions is

presented below.

CONCERNING THE WIDTH AND THE LENGTH

OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

According to the scale-drawn plan made by Father Gabriel

Hecht, in 1725-26 the nave of the medieval church had a

length of 155 feet. Its clear inner width was 46 feet, that of

the aisles 23 feet. The two clerestories rested on sixteen

piers, each 3 feet square. They were placed at intervals of

17 feet (measured on center) and had between them a clear

arcade span of 14 feet.[13]

Hardegger could establish that

Gabriel Hecht, in measuring the medieval building as well

as in laying out his own drawings availed himself of the

so-called Württemberg foot[14]

which had a unit value of

28.6 cm., and consequently was considerably smaller than

the foot used in drafting the Plan of St. Gall. Hardegger

thought that the architect who drew the Plan of St. Gall

scaled his layout with a foot that formed an equivalent of

33.3 cm.[15]

Converted to this scale, the measurements

recorded by Gabriel Hecht would read as follows: length

of nave: 133 feet; clear width of nave: 40 feet; clear width

of aisles: 20 feet; clear span of the arcade openings: 12 feet.

This in complete harmony with the dimensions stipulated

in the explanatory titles of the Plan of St. Gall, with one

difference only: the builders of Gozbert's church interpreted

509.X MATTHAEUS MERIAN. ABBEY AND CITY OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW FROM THE EAST

ETCHING: 20.7 × 31.2cm. FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1638 & BASED ON THE MELCHIOR FRANK ETCHING, FIG. 507

Merian's etching defines with great clarity the tripartite division of the post-medieval city; the abbey, the upper, and the lower town all

separated from one another by high girdle walls. The city by now had grown to more than six times the ground area of the monastery in the

shadow of which it had arisen. The wedge-shaped boundaries of the rise of land on which the monastery was built are distinctive. (For

identification of the parts of the Church with its staggered roof levels, see caption to fig. 513.)

Noteworthy among the medieval buildings east of the Church are: the circular chapel of St. Gallus (built 958-971) and north of it St. Peter's

chapel, the oldest sanctuary on the grounds and dating from before the incumbency of Abbot Gozbert. East of it and in axial prolongation lies

St. Catherine's chapel, where the monk Tutilo was buried in 912, and that served as chapel for the abbot's palace. (The latter, a tall building

north of St. Catherine's, is not identical with the PALATIUM built by Grimoald, abbot from 841-872, and gutted by fire in 1418; it may have

been located further west.

509.Y JOHANNES ZUBER, CADASTRAL PLAN

OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL & ENVIRONS, 1835.

[scale of figure 509.Y as shown, about 1:11,500]

ST. GALL, STADTBIBLIOTHEK, CH 9000. SIZE OF ORIGINAL: 53 × 746m

[By courtesy of the Stadtbibliothek]

The plan carries the title GRUNDRISS DER STADT ST. GALLEN NEBST DER

UMGEBUNG AUFGENOMMEN VON

JOH. ZUBER. LITHOGRAPHIE VON HELM UND SOHN, ST. GALLEN, 1835.

509.Z DETAIL Central portion of St. Gall with the cathedral (shown at about 1:11,500)

source: STADT S. GALLEN, 1964, 1:5000 Art Institut Orell Füssli AG Zurich, 1964

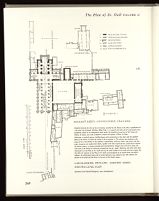

510. PATER GABRIEL HECHT. "ICHNOGRAPHIA"

MEASURED PLAN OF THE MONASTERY OF ST. GALL DATED A.D. SEPTEMBER 1719 ST. GALL, STIFTSARCHIV

KARTEN UND PLÄNE, M.83

[By courtesy of the Stiftsarchiv]

The disposition of church and cloister are basically the same as those shown on the etching of Melchior Frank (fig. 507), except that the church

was enlarged westward in 1623-26 by two bays that absorbed the space formerly occupied by St. Michael's chapel. All of the smaller chapels to

the east of the Church (St. Gall, Holy Sepulchre, St. Peter's, St. Catherine's) were demolished during a building campaign undertaken by

Abbot Gallus II Alt in 1666-1671. He erected a long wing of domestic facilities east of the church (nos. 18-25) including a new dining room

and audience hall for the abbot (no. 18) and a new chapel for St. Gall (no. 19), new lodgings for the porter (no. 20) and beyond the passage

beneath the porter's lodging, servants' quarters, a bakery, and a pharmacy (nos. 21-25). The old but decaying abbot's palace remained at its

original site (no. 48) but the site of St. Peter's and St. Catherine's was now occupied by a carriage house (no. 32).

511.A PATER GABRIEL HECHT. MEASURED PLAN OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION

ORIGINAL FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK,

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 4]

Gabriel Hecht retains the church of Otmar, the nave and aisles of Gozbert's church, as well as Eglolf's choir. He adds on either flank of the church

two continuous rows of chapels, and converts the last two bays of the nave into a pseudo-transept surmounted by a tower.

of the Plan worked with a 40-foot square, the corners of

which coincided with the center of every second arcade

support. Being composed of nine arcades of spans of 12

feet on center, the nave of the Plan of St. Gall would have

had a clear inner length of 108 feet. If one adds to this the

thickness of the eight piers, each of which was 3 feet square,

one arrives at a clear inner length of 132 feet, which corresponds

within a margin of error of only 1 foot to the layout

of the church measured by Gabriel Hecht. To place this

figure into proper historical perspective, the reader must

be reminded of the fact that Abbot Gozbert's church was

two bays shorter than the church which Father Gabriel

had before him. Before 1623 the two westernmost bays of

the church were taken up by an open porch, surmounted by

a chapel that was dedicated to St. Michael (fig. 513). This

chapel was built after Gozbert's death as a connecting link

between the main church and the church of St. Otmar.

Consecrated in 867, it was taken down to make room for

an enlargement of the monastery church by two additional

bays when the chapel of St. Otmar was rebuilt, between

1623 and 1626.[16] If one subtracts the length of these two

added bays (34 Württemberg feet or 23 Carolingian feet)

from the total length of the nave (155 Württemberg feet or

133 Carolingian feet) one arrives at an original length of

121 Württemberg feet or 105 Carolingian feet. This comes

as close to the 108 feet of the nave of the Plan as one could

expect, in absence of any more tangible archaeological

information. It left 95 more feet of the total length of 200

511.B PATER GABRIEL HECHT. LONGITUDINAL SECTION OF ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION. FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 5]

apse.[17]

Hardegger, 1917, 47; Poeschel, 1961, 31 accepts this interpretation

of the scale of the Plan. Hardegger's assumption was confirmed by our

own calculations (cf. I, 95-97).

Hardegger's interpretation of the measurements furnished by

Gabriel Hecht find confirmation in the measurements recorded by

Johannes Caspar Glattburger, in 1917, as Erwin Poeschel has pointed

out (Poeschel, 1961, 30ff). As already mentioned, they are, recorded

in Acta monasterii, B. 322 p. 839 and 841. Glattburger, who like Gabriel

Hecht used the Württemberg foot, listed the total length of the church

as 272 feet. If one subtracts from this figure the 34 Württemberg feet of

the two added westernmost bays of the church, one arrives at a total

length of 238 Württemberg feet or the equivalent of 206 Carolingian

feet, again close enough to justify the assumption that Gozbert complied

with the explanatory title of the Plan that stipulated that the church

should only be built to a length of 200 feet.

CONCERNING THE LAYOUT OF THE TRANSEPT

AND THE CHOIR OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

In examining the drawings of Gabriel Hecht, Hardegger

observed that the dimensions of the choir built by the

abbots Eglolf and Ulrich VIII between 1439 and 1483

corresponded almost precisely to the layout of the eastern

portion of the Church of the Plan.[18]

He felt convinced

that the masonry of Eglolf's choir followed the lines of the

Carolingian work (figure 512A-C). Eglolf apparently had

simply merged the space of the crossing of Gozbert's church

with that of its presbytery, converting them into the nave

of a choir whose aisles extended to the eastern end of the

church, but did not project laterally beyond the body of

Gozbert's church. The new choir absorbed in its mass

the subsidiary spaces which in the church of the Plan

accommodated Scriptorium and Library.

Hardegger's observations were keen and his argument

is persuasive. One fails to understand why he had so little

influence on the controversy generated by those who tried

to resolve, in retrospect, what a Carolingian architect might

have done had he redrawn the Church of the Plan in the

light of the corrective measurements given in its explanatory

titles.[19]

To leave choir and transept intact made sense

in functional terms: it was here that the monks were

stationed during their religious services for a total of four

hours each day.[20]

To effect the required reduction of

space by changing the dispositions of the nave also made

sense, for here the loss of space was incurred not by the

monks, but by the laymen, who attended only a fraction of

511.C PATER GABRIEL HECHT. EXTERIOR ELEVATION OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION. FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 18]

not on a regular schedule.

Otmar, a man of noble Alemannic birth, raised in the episcopal city

of Chur in Raetia, became abbot of the monastery of St. Gall in 719

and died in exile on the island of Werd in the Rhine River in 759. For

these and other bibliographical details and sources see Duft, 1959, 17.

The most recent review of what is known about Otmar's Church is in

Poeschel, 1961, 7-9.

See Poeschel, 1961, 41ff; Hardegger, 1917, passim; idem in Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess,

1922, passim.

For descriptions and reproductions of these drawings, see Poeschel,

1957, 38-39 and ibid., fig. 46 (Heinrich Vogtherr), figs. 53 and 54

Melchior Frank), fig. 56 (pen drawing of 1666) and fig. 57 (bird's-eye view

on parchment of 1671).

On the Protestant upheaval of 1712, see Hardegger, 1917, 1ff;

Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess, 1922, 168ff; Poeschel, 1961, 65ff.

Before World War II, these drawings, bound into a fascicule, were

in the Stiftsarchiv of St. Gall (cf. Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess, 1922,

173 note 1). After their evacuation during the war, their whereabouts

were no longer traceable (cf. Poeschel, 1961, 45, note 4).

VI.1.3

THE CLOISTER

It is clear that the cloister lay to the south of the church

where it still is today (although completely rebuilt), and it

is equally clear that the dormitory occupied the upper level

of the eastern range which adjoined the southern transept

arm precisely as on the Plan of St. Gall. This can be

inferred from Ekkehart's account of the ignominous visit

which Abbot Ruodman of Reichenau paid to the monastery

of St. Gall under the cover of night and the description

of the complicated route which he had to take in order to

get from the cloister to the monks' privy.[21]

From the same

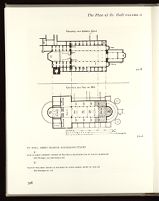

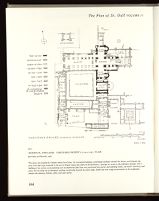

ST. GALL. ABBEY CHURCH. SUCCESSIVE STAGES

512.B

512.A

A.

PLAN OF ABBOT GOZBERT'S CHURCH OF 830-837 AS RECONSTRUCTED BY AUGUST HARDEGGER

[after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 521]

B.

PLAN OF THE ABBEY CHURCH AS RECORDED BY PATER GABRIEL HECHT IN 1725-26

[after Hardegger, loc. cit.]

512.C ST. GALL. ABBEY CHURCH. LONGITUDINAL SECTION OF 1626-1756 AS RECONSTRUCTED BY

AUGUST HARDEGGER ON THE BASIS OF GABRIEL HECHT'S DRAWINGS OF 1725-26 (FIGS. 511.A-C)

[after Hardegger, 1922, 139]

FIGURES 512. A, B, C ARE SAME SCALE (CA.1:700)

Bays 3-9 of the nave and aisles were built by Gozbert and are the oldest parts, dating from 830-837. Otmar's church, dedicated 24

September 867, located west of Gozbert's church was originally separated from it by an entrance hall surmounted by St. Michael's chapel

which was dedicated 25 September 867 (cf. figs. 513.A-B, and figs. 507-509). The choir was entirely built by Eglolf, 1439-1483, on a ground

area co-extensive with the transept and choir of Gozbert's church that had been damaged by fire in 1418. In 1623-26 St. Michael's chapel

was demolished and Gozbert's church was enlarged westward by two bays, thus extending it all the way to Otmar's church.

the entrance of the church, as we would expect it to be in

the light of the Plan of St. Gall. Ekkehart IV mentions a

warming room (pyrale) in a context which suggests that in

the tenth and early eleventh century it was used for disciplinary

actions traditionally undertaken during chapter

meetings.[22] In the same chapter he also implies that the

washhouse (lavatorium) was reached from the warming

room; in fact the text seems to suggest that it was part of

this room. In departure from the Plan of St. Gall, however,

the Scriptorium was not on the north side of the church

but next to the pyrale.[23]

We know nothing about the location of the refectory

or the cellar but there is no reason to presume that they

were laid out in a manner other than that proposed on the

Plan. The Carolingian refectory and dormitory perished

in the great fire of 1418 and were completely rebuilt by

Abbot Eglolf (1427-1442).[24]

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 112; ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 379ff; ed. Helbling, 1958, 192-93.

VI.1.4

EXTRA-CLAUSTRAL BUILDINGS

Ekkehart's account of the fire of 937[25]

discloses that the

Outer School was located north of the church on a lot

which corresponded closely to the site it occupies on the

Plan of St Gall. The fire was set by a vindictive student in

the attic of the schoolhouse and was carried by the north

wind on to the roofs of the church and of the cloister.

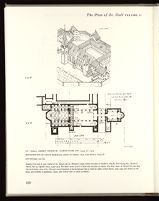

ST. GALL ABBEY CHURCH. CONDITION OF 1439 TO 1525

513.B

513.A

RECONSTRUCTION BY AUGUST HARDEGGER, BASED ON FRANK, 1507, AND HECHT, 1725-26

[after Hardegger, 1922, 69]

Reading from west to east: church of St. Otmar and St. Michael's chapel (above entrance to Gozbert's church), both dating 867; Gozbert's

church, 830-37; Eglolf's choir, 1439-1483; Hartmut's tower (SCHULTURM) near entrance to church, 872-883; tower of Ulrich (VI) von Sax

(FESTERTURM), 1204-1220. The four-storied building in the background (HELL) built by Abbot Ulrich Rösch, 1463-1491 (not shown on the

plan), was probably a guesthouse. (Dates after Otmar refer to tenure of abbots.)

514. THE PLAN OF ST. GALL IMPOSED ON A CADASTRAL PLAN OF ST. GALL OF 1965

RED DRAWING, PLAN OF ST. GALL, SHOWN 1/8 ORIGINAL SIZE (1:1536) IMPOSED ON CADASTRAL PLAN AT SAME SCALE

Even a cursory glance at the shape of the site to which the monastery was confined discloses that it could not have been an easy task to

attempt literally to superimpose the rectangular scheme of the Plan of St. Gall upon so irregular a plot. The superimposition emphazises the

ideal character of the Plan and foreshadows adjustments that, in ensuing centuries, were to be made in many other places where the topography

of a particular site prevented complete realization of the ideal monastery of the Plan.

In order to be built on this particular site, as foreseen on the Plan, the Great Collective Workshop, the Granary, the houses for fowl and their

keepers, the Gardener's House, most of the Monks' Vegetable Garden, and even a corner of the cemetery, would have had to lie across the

gorge of the Steinach, that at its lowest point lay some 50 feet lower than the monastery ground level. (cf. caption, figure 505, and similar

superimpositions made by Hardegger, 1922, 22, fig. 3; and Edelmann, 1962, 289.) This drawing also shows that the ground area of the Baroque

church of St. Gall is congruent not only with that of the church as originally conceived on the Plan but also with the surface area the entire

aggregate the medieval churches had attained after Otmar's church had been added to Gozbert's church (cf. fig. 513).

On the Plan of St. Gall the Abbot's House is located

east of the Outer School in axial prolongation of the northern

transept arm of the Church. The palace (palatium),

built by Abbot Grimoald (841-847) with the aid of masons

from the imperial court (palatini magistri) was also to the

north of the church although further eastward. A deed

of 1414 reveals that it was furnished with a solarium; as is

stipulated on the Plan of St. Gall. Like most of the other

buildings it was gutted by the fire of 1418 and subsequently

completely reroofed as well as rebuilt internally by Abbot

Henry IV and his successor Eglolf (1427-43).[26]

On the

Ichnographia drawn by Gabriel Hecht in 1719, (fig. 510),

and in the bird's-eye view of the city of St. Gall issued by

Melchior Frank in 1595 (fig. 507), as well as on the anonymous

city view of 1666,[27]

this rebuilt variant of the

Carolingian palace is truthfully portrayed.

The original cemetery of the monks was east of the

monastery church between the chapel of St. Peter's and

the Steinach River[28]

on precisely the same location in

which it was shown on the Plan of St. Gall; and St.

Peter's itself[29]

(perhaps in conjunction with St. Catherine's

chapel) lay on the site that on the Plan is occupied by a

double chapel that served as oratories for the novices and

the sick. It consisted, as can be inferred from the city view

of Melchior Frank (fig. 507) and several other drawings, of

three contiguous building masses of varying width and

height arranged along the same axis.

Here our knowledge of the position of the offices of the

Carolingian monastery ends. Whatever evidence survives

of their original disposition is hidden in the ground. The

city and the canton of St. Gall, not to speak of the Confederation

of Switzerland, whose support would be needed

in a project of this magnitude, have not faced as yet the

challenge of clarifying this important historical problem

through a program (long overdue) of systematic excavations.

In the meantime it must be underscored that in those

cases for which historical evidence is available, the layout

of Gozbert's monastery appears to have conformed with

the scheme of the Plan. This condition may even have

applied to most of the unknown sectors of the site, except

for the Hen and Goose Houses in the southeastern corner

of the Plan. Their location is in conflict with the relief of

the actual plateau on which the abbey rose. Here the steep

embankment of the Steinach River, that swings sharply

toward the north, would have called for adjustments that

might also have affected some of the neighboring buildings.

A glance at the city view of Melchior Frank (fig. 507) and

the photographs of the monastery site, forming part of the

magnificent model reconstruction of the city of St. Gall,

made in 1919-22 by architect Salomon Schlatter (figs. 508

and 509) reveals this condition with great clarity. In

figure 514 we have superimposed the course of the river

and other boundaries of the monastery site upon the scheme

of the Plan. The axis of the church is given by its still-existing

crypt. The superimposition shows that between

the church and the Steinach there is sufficient room for all

of the buildings that on the Plan are located to the south of

the Church. The houses for the animals and their keepers to

the west of the Church, could easily have been accommodated

in the great area that now is occupied by the St.

Gallus Platz.[30]

The original entrance to the monastery was

in the west, as it is on the Plan of St. Gall, through the

Gallustor (later: Grüner Turm).[31]

The only truly distinctive

difference between the scheme of the Plan and the actual

monastery was that Gozbert's church did not terminate

with an apse in the west—understandably so because in

St. Gall, St. Peter, to whom this apse is dedicated on the

Plan, had already a sanctuary of his own.[32]

In the Abbey of

St. Gall, instead, this area was occupied by a chapel

dedicated to St. Otmar and connected with the church by

an open porch that was surmounted by an oratory dedicated

to St. Michael (fig. 513). St. Otmar's chapel was built by

Abbot Grimald and consecrated on September 24, 867 by

Bishop Salomon.[33]

It rose on the space that was released on

the actual building site by the reduction of the church as

originally drawn on the Plan from 300 to 200 feet. The only

point in which Hardegger failed was that in his reconstruction

drawings of Gozbert's church (fig. 512A) he did not

remain faithful to his own argument but allowed the two

transept arms to project beyond the masonry of the Gothic

choir (obviously in the desire to make them more fully

conform with the Plan). H. R. Sennhauser informs me that

this was not borne out by excavations conducted under the

pavement of the present church, which showed that the

circumference walls of the Gothic choir rose indeed, as

Hardegger had postulated, on the foundations of the

corresponding Carolingian work (see below, pp. 358-59).

FRANCISC (FRANZISKA, FRANSISQUE)

A favorite weapon of the Franks, wielded with great dexterity as a battle axe, often hurled.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 67; ed. Meyer von Knonau,

1877, 240-43; ed. Helbling, 1958, 127-28.

On the original site of the monk's cemetery see Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess,

1922, 265ff and Poeschel, 1961, 78ff.

VI. 2

THE MONASTERY OF CLUNY,

BUILT BY

ABBOT ODILO, 994-1048

VI.2.1

ITS DESCRIPTION IN THE SO-CALLED

CUSTOMS OF FARFA

Our first complete description of the layout of a Benedictine

monastery later than the Plan of St. Gall is found

in a chapter of the so-called Customs of Farfa (Consuetudines

Farfenses) written between 1030 and 1048.[34]

These customs were believed to pertain to the monastery

of Farfa near Rome, until Dom Ursmer Berlière and Dom

Hildephonsus Schuster showed that they were the customs

of Cluny recording the layout of the monastery built by

Abbot Odilo of Cluny (994-1048).[35]

The chapter of the

Farfa text with which we are here concerned falls into two

parts: a description of the layout of the claustral range of

buildings, and a description of the layout of buildings

located peripherally around this complex.[36]

Since it forms

the basis for conclusions set forth on the pages that follow,

we feel compelled to quote it verbatim:

LUTTRELL PSALTER

The Psalter, dating ca. 1340, appears to have only these three owls (border ornament, fol.

177v) among its illustrations. They are redrawn here as line interpretations the same size as

the originals.

THE FARFA TEXT HAS BEEN COMPOSED WITH TRANSLATION IN "PARALLEL TEXT" STYLE

I. Ecclesiae longitudinis CXL pedes, altitudinis XL et tres, fenestrae

vitreae CLXta. Capitulum vero XL et V pedes longitudinis, latitudinis

XXXta et IIIIor. Ad oriente fenestrae IIIIor; contra septemtrionem

tres. Contra occidentem XIIci balcones, et per unumquemque afixe in eis

duae columnae. Auditorium XXXta pedes longitudinis; camera vero

nonaginta pedes longitudinis. Dormitorium longitudinis Ctū LXta

pedes, latitudinis XXXta et IIIIor. Omnes vero fenestrae vitreae, quae

in eo sunt XCta et VIIte et omnes habent in altitudine staturam

hominis, quantum se potest extendere usque ad summitatem digiti,

latitudinis vero pedes duo et semissem unum; altitudinis murorum XXti

tres pedes. Latrina[37]

LXXtē pedes longitudinis, latitudinis XXti et

tres; sellae XL et quinque in ipsa domo ordinatae sunt, et per

unamquamque sellam aptata est fenestrula in muro altitudinis pedes duo,

latitudinis semissem unum, et super ipsas sellulas compositas strues[38]

lignorum, et, super ipsas constructionem lignorum facte sunt fenestrae

Xcē et VIItē, altitudinis tres pedes, latitudinis pedem et semissem.

Calefactorium XXtt et Ve, pedes latitudinis, longitudinis eademque

mensura.[39]

A janua ecclesiae usque ad hostium calefactorii pedes

LXXV. Refectorium longitudinis pedes LXXXXta, latitudinis XXV;

altitudinem murorum XXtt tres, fenestrae vitreae, quae in eo sunt ex

utraque parte octo, et omnes habent altitudinis pedes V, latitudinis tres.

Coquina regularis XXXta pedes longitudine, et latitudine XXtt et V.

Coquina laicorum eademque mensura. Cellarii vero longitudo LXXta,

latitudo LXta pedes.

Aelemosynarum quippe cella pedes latitudinis Xcē, longitudinis

LXta ad similitudinem[40]

latitudinis cellarii. Galilea longitudinis LXta

et quinque pedes et duae turraes ipsius galileae in fronte constitute; et

subter ipsas atrium est ubi laici stant, ut non impediant processionem.

A porta meridiana usque ad portam aquilonarium pedes CCLXXXta.

Sacristiae pedes longitudinis L et VIII cum turre, quae, in capite ejus

constituta est. Oratorium sanctae mariae longitudinis XL et quinque

pedes, latitudines XXti, murorum altitudinis XXti et tres pedes.

Prima cellula informorum latitudinem XX et VIItē pedes, longitudinem

XX et tres cum lectis octo et sellulis totidem in porticum juxta

murum ipsius cellulae de foris, et claustra praedictae cellulae habet

latitudinis pedes XIIci. Secunda cellula similiter per omnia est coaptata.

Tertia eodemque modo. Similiter etiam et quarta. Quinta sit

minori ubi conveniant infirmi ad lavandum pedes die sabbatorum: vel

illi fratres, qui exusti sunt ad mutandum. Sexta cellula praeparata[41]

sit

ubi famuli servientes illis lavent scutellulas, et omnia utensilia. Juxta

galileam constructum debet esse palatium longitudinis Ctū XXXta et

Ve pedes, latitudinis XXXta, ad recipiendum omnes supervenientes

homines, qui cum equitibus adventaverint monasterio. Ex una

parte ipsius domus sunt praeparata XLta lecta et totidem pulvilli ex

pallio ubi requiescant viri tantum, cum latrinis XLta. Ex alia namque

parte ordinati sunt lectuli XXXta ubi comitisse vel aliae honestae

mulieres pausent cum latrinis XXXta, ubi solae ipsae suas indigerias

procurent. In medio autem ipsius palatiis affixae sint mense sicuti

refectorii tabulae, ubi aedant tam viri quam mulieres.

In festivitatibus magnis sit ipsa domus adornata cum cortinis et

palliis et bamcalibus in sedilibus ipsorum. In fronte ipsius sit alia

domus longitudinis pedes XLta et V, latitudinis XXXta. Nam ipsius

longitudo pertingant usque ad sacristiam, et ibi sedeant omnes sartores

atque sutores ad suendum, quod camerarius[42]

eis praecipit. Et ut praeparatam

habeant ibi tabulam longitudinis XXXta pedes, et alia tabula

afixa sit cum ea, quarum latitudo ambarum tabularum habeat VIItē

pedes. Nam inter istam mansionem et sacristiam atque aecclesiam, nec

non et galilaeam sit cimiterium, ubi laici sepeliantur. Ad porta meridiana

usque ad portam VIItem trionalem contra occidentem sit constructa

domus longitudinis CCtū LXXXta pedes, latitudinis XXti et V,

et ibi constituantur stabule equorum per mansiunculas partitas, et

desuper sit solarium, ubi famuli aedant atque dormiant, et mensas

habeant ibi ordinatas longitudinis LXXXta pedes, latitudinis vero

IIIIor. Et quotquot ex adventantibus non possunt reficere ad illam

mansionem, quam superius diximus, reficiant ad istam. Et in capite

ipsius mansionis sit locus aptitatus, ubi conveniant omnes illi homines,

qui absque equitibus deveniunt, et caritatem ex cibo atque potum in

quantum convenientia fuerit ibi recipiant ab elemosynario fratre. Extra

refectorium namque fratrum LXta pedum in capite latrine sint cryptae

XIIci, et todidem dolii praeparati, ubi temporibus constitutis balnea

fratribus praeparentur; et post istam positionem construator cella

novitiorum, et sit angulata in quadrimodis, videlicet prima ut meditent,

in secunda reficiant, in tertia dormiant, in quarta latrina ex latere.

Justa istam sit depositam alia cella, ubi aurifices vel inclusores seu vitrei

magistri conveniant ad faciendam ipsam artem. Inter cryptas et cellas

novitiorum atque aurificum habeant domum longitudinis Ctum, XXti et

quinque pedes, latitudinis vero XXti et quinque et ejus longitudo perveniat

usque ad pistrinum.[43]

Ipsum namque in longitudinem cum turrem,

quae in capite ejus constructa est, LXXta pedes, latitudinis XXti.

END OF PARALLEL TEXT TREATMENT

(After Albers, Cons. Mon, I, 1937-39)

I. The length of the church is 140 feet, the height 43 feet, with 160

glass windows. The chapter house is 45 feet long, 34 feet wide with

four windows on the east, three on the north. On the west are

twelve arches with two columns affixed to each. The inner parlor is

30 feet long. The camera, 90 feet long. The dormitory is 160 feet

long, 34 feet wide. All the windows are glass, 97 in total, as tall as a

man extending his arm, and 2½ feet wide. The walls are 23 feet

high. The latrine is 70 feet long, 23 feet wide. In that building there

have been arranged 45 seats with a small window above each seat,

2 feet high, ½ foot wide. Above those seats is built a wooden structure

and above this wooden construction, there are 17 windows,

3 feet high, 1½ feet wide. The warming room is 25 feet wide, and

the same in length. From the door of the church to the door of the

warming room there are 75 feet. The refectory is 90 feet long, 25

feet wide. The height of the walls is 23 feet; there are glass windows,

eight on each side, 5 feet high and 3 feet wide. The monks' kitchen

is 30 feet long, 25 feet wide. The lay kitchen has the same dimensions.

The cellar is 70 feet long, 60 feet wide. The almonry is 10

feet wide, 60 feet long, the same width as the cellar. The narthex is

65 feet long with two towers placed in front of it. Underneath is an

atrium where the laity stand so as not to impede the processions.

From the south entrance to the north, there are 280 feet. The length

of the sacristy is 58 feet with the tower, which is at its head. The

feet high. The first cell of the sick is 27 feet wide and 23 feet long

with eight beds and as many seats outside in the portico of that cell,

and the cloister of that cell is 12 feet wide. The second cell is the

same in all respects. Also the third and the fourth. Let a fifth be

smaller, where the sick might come to wash their feet on the

sabbath, or those brothers who have been burnt to change [their

bandages]. A sixth cell should be prepared where the servants attending

them can wash the pans and all the utensils. Near the narthex

must be built a house for distinguished guests 135 feet long, 30 feet

wide, to receive all the visitors who, along with their squires, shall

come to the monastery. On one side of that house have been prepared

forty beds and as many straw matresses for the repose of as

many men, and forty latrines. On the other side have been arranged

thirty beds where countesses or other noble women can rest, with

thirty latrines where alone they can see to their needs. In the center

of that lodging there should be placed tables like those of the

refectory, where both the men and the women can eat.

During the great holidays that house should be decorated with

curtains and drapes and bench coverings. In front of that house let

there be another, 45 feet long, 30 feet wide. Its length should reach

clear to the sacristy, and in it should sit all the cobblers and tailors,

who sew what the chamberlain tells them. They should have there a

table 30 feet long, and another table joined to it. Both tables should

be 7 feet wide. Between that house and the sacristy and the church

and also the narthex there should be a cemetery for the burial of the

lay. From the south gate to the north gate let there be built on the

west a house 280 feet long, 25 feet wide for the separate stalls of the

horses, and above that a solarium where the servants can eat and

sleep. They should have tables 80 feet long, 4 feet wide, and when

they cannot feed some of the visitors at the above-mentioned

building, they should feed them at this one. At the head of that

building let there be a place where those can come together who

arrive without squires and there receive from the alms brother

sufficient charity in the form of food and drink. Outside of the

refectory of the brothers 60 feet from its head twelve latrines should

be dug and as many baths, where at fixed times the brothers can

bathe. After that location let the cell of the novices be built and it

should be divided off into four parts: in the first they might meditate;

in the second, ear; in the third, sleep; and the fourth have a

latrine on the side. Next to that one let there be built another cell

where the goldsmiths or jewelers or glaziers come for their craft.

Between the latrines and the cells of the novices and of the goldsmiths

they should have a house 125 feet long, 25 feet wide and its

length should extend to the bakery. Its length including the tower

at its head is 70 feet, its width, 20 feet.

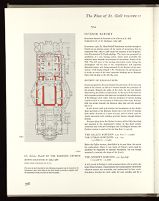

515. CLUNY. PLAN OF MONASTERY ABOUT 1050

REDRAWN FROM CONANT, VARIOUS VERSIONS

Cluny sprang from a nucleus of five or six monasteries united by its first abbot,

Berno (909-927). Under the leadership of Abbot Odo (927-942) and his

successors, and vigorously supported by the Papal See, Cluny became the

center of an order that included, by about 1150, no fewer than 314 monasteries

all over Europe as well as the Holy Land.

The fabric of Cluny was almost utterly destroyed during the French Revolution.

Through intimate knowledge of the topography and archaeology of the site,

superior draftsmanship, and an ingenious synthesis of historical sources,

Kenneth John Conant has reconstructed the various stages of the architecture of

this great center of monastic reform, thus making a major contribution to its

visual history.

The church of this plan, Cluny II, was built by Abbot Mayeul around

954-981, perhaps over the court of the original villa given to its monks in 910.

The adjoining conventual buildings were erected ca. 991-1048 by Abbot Odilo,

replacing Mayeul's claustrum. Conant believes that Odilo rebuilt the east and

west ranges of the cloister outside Mayeul's buildings, thus taking them out of

alignment with the transept and façade of Mayeul's church, thereby forming the

peculiar L-shaped bend of the northern cloister walk where it clears the transept.

Insertion of a chapter house in the east range, together with the small size of

both Odilo's cloister yard and Mayeul's church caused extension of the east

range beyond the limits of the cloister square—a feature that in the 12th century

became widespread among independent Benedictine churches of England (figs.

516, 518); and standard among 12th-century Cistercian houses (figs. 519-521).

Attempts to convert the prose account of the monastery

described in the Consuetudines Farfenses into a graphic

reconstruction were made by Julius von Schlosser in 1889,

by Georg Hager in 1901, and by A. W. Clapham in 1934.[44]

The views set forth by these scholars have been expanded

and refined by Kenneth John Conant in a series of studies

published over a period of nearly thirty years.[45]

Schlosser

felt that the Latin text was confused, ambiguous, and

disconnected, and consequently assumed that the description

of the buildings around the cloister followed no logical

order. He had overlooked the dimensional clues in the

text which could help to clarify the order.[46]

Hager made use

of these clues and, by grouping buildings of identical widths

together, discovered that the author of the text describes

the monastery in a continuous order away from the church

and clockwise around the compound of the cloister, describing

first the east range, then the south range, and finally

the west range. Hager noted that the resulting order coincided

with the layout of later monasteries, in particular that

of the Abbey of St. Peter and Paul of Hirsau, which he used

as a model for his reconstruction.[47]

Conant focused upon the task of superimposing the order

of buildings recorded in the Farfa text upon the actual

building site of the monastery of Cluny, and in doing so,

demonstrated that the Farfa text was compatible with the

topography of Cluny. Conant published his findings in a

number of plans; the latest in 1965 (fig. 515) and 1968.

In developing these schemes he depended upon a plan of

the monastery of Cluny drawn up between 1700 and 1710

(now in the Musée Ochier), and to some extent on the

results of his excavations conducted from 1928 onwards

with the permission of the French authorities under the

auspices of the Medieval Academy of America.

The Farfa description discloses that the monastery built

toward the middle of the eleventh century by Odilo of

Cluny was, in its basic features, still like the layout of the

buildings shown on the Plan of St. Gall. There are of course

some modifications—most notably the introduction of a

separate chapter house at the head of the east range—but

these changes remain within the framework set forth on

the Plan of St. Gall.

Julius von Schlosser, who believed that the writer of the description

had before him an ideal drawing like that of the Plan of St. Gall, observed

that for the first part of the description the measurements and definitions

are given in the indicative mood, whereas, beginning with the description

of the Infirmary the mood changes to the hortative subjunctive. He

inferred from this that the buildings referred to in the indicative were

already built when the text was written about 1043, while those referred

to in the subjunctive had as yet not been constructed. Schlosser, 1889,

42 and 46.

VI.2.2

LAYOUT OF THE

CLAUSTRAL BUILDINGS

As on the Plan of St. Gall, the cloister at Cluny lies to

the south of the church. The east range contains the

dormitory and its annexes; the south range, the refectory

and the kitchens; the west range, the cellar and the parlor.[48]

EAST RANGE

In Cluny, as on the Plan, the monks' dormitory (dormitorium)

occupies the second floor of the east range. The Farfa

text describes it as 160 feet long and 34 feet wide, with walls

reaching to a height of 23 feet. But in the space below the

dormitory some important innovations have been made.

On the Plan of St. Gall, this entire space is occupied by the

Monks' Warming Room coextensive with the dormitory of

40 feet by 85 feet overhead. In Cluny, this space is internally

divided into a chapter house (45 feet long and 34 feet wide);

an auditorium (30 feet long); and a camera (90 feet long).

The Monks' Warming Room (calefactorium) has been reduced

at Cluny to a surface area of only 25 feet by 25 feet

and shifted into the south range. This amounts to complete

reassignment of the space beneath the dormitory, a modification

for which an explanation will later be offered.[49]

Chapter house

In the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall the chapter

meetings were held in the northern cloister walk, which

was made wider (15 feet) than the other three walks (12½

feet) and furnished with benches.[50]

The same arrangement,

as has been shown above, prevailed at Fontanella, which

might indicate that the cloister walk next to the church was

the common location for the capitulum in Carolingian

times.[51]

Attempts made by Hager and others to show that

a separate chapter house existed at Jumièges in the seventh

century, at Reichenau in 780, at Fontanella by 823-833,

and in the monastery of St. Gall after 830, can be shown to

be based on faulty textual exegesis, and in one case on the

use of a corrupted text.[52]

To use the northern cloister walk for chapter meetings,

however, had disadvantages. Although warmed by the

rays of the sun in the winter, when the arc of sun is in

the southern hemisphere, and sheltered from the north

wind by the church, the open cloister walk offered little

protection from inclement weather. The physical discomforts

endured in the winter or on rainy days must have

called early for a more protected location for the chapter

meetings.

Certain passages in the Casus Sancti Galli of Ekkehart IV

(980-1060) suggest that in the abbey of St. Gall chapter

meetings were then held in the Monks' Warming Room.

It is quite possible that the special room for chapter meetings

at Cluny II owes its existence at the head of the east

range to the desire to convert into a separate space a portion

of the former warming room that in the earlier days had

served temporarily for chapter meetings during inclement

weather. Ekkehart mentions that on the order of the abbot,

a raging monk was punished during a chapter meeting by

being "bound to a column of the warming room and

harshly beaten," (ad columpnam piralis ligatus acerrime virgis

caeditur).[53]

Another passage indicates that the pyrale was

the traditional place for punishment in the monastery,

since it was there that the whip was kept.[54]

Punishment

was traditionally carried out in the chapter house in the

Middle Ages. This practice seems already to have been

current in the time of Ekkehart IV, since a text from

Paderborn of 1023 explicitly states that punishment was

administered in the chapter house.[55]

Eckeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 141; ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 440-42; ed. Helbling, 1952, 232-34.

Ibid., chap. 36: Ratperte autem mi, rapto flagello fratrum quod

pendet in pyrali, de foris, accurre! ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 133-37;

ed. Helbling, 1952, 77-80.

Lehman-Brockhaus, I, 1938, 210, no. 1044, Vita Meinwerci episc.

Patherbrunnemsis: "Illico canonicis in capitolium principalis ecclesie convocatis

capellanum imperatoris huius rei conscium durissime verberibus

castigari iussit."

Inner parlor

Its name (auditorium) in the Farfa description suggests that

it served as an area where monks might talk to one another

when silence was being observed in the rest of the cloister.[56]

Supply room

The largest architectural entity in the east range after the

dormitory is a space 90 feet long and 34 feet wide which in

the Farfa text is designated as camera, that is, "store-" or

"supply room".[57]

It is too far away from the kitchen to be

interpreted as a pantry or larder. Since the Farfa description

lacks any reference to a vestiary in which the clothes

of the monks are kept, it is possible that this room was a

storehouse for clothing and such other material necessities

that were furnished by the camerarius (chamberlain) who

was in charge of the workmen and craftsmen. On the Plan

of St. Gall, the monks' clothing was kept, and perhaps even

tailored, in the large vestiary which formed a second story

over the refectory (40 feet by 100 feet). Since the generous

clothing allowance provided by the synod of Aachen in

816 was adopted by Cluny, the storeroom for clothing would

need to be about the same size as that of the Vestiary on

the Plan of St. Gall.[58]

One of the primary changes necessitated by the inclusion

of the chapter house and inner parlor in the east range was

that these additions made this range along with its annexes

(the monks' bath and privy) extend southward well beyond

the cloister square. In other respects, the relative position

of the dormitory, privy, and bathhouse are identical with

those on the Plan of St. Gall.

Du Cange, sub verbo indicates that camera refers to some kind of

store room, usually a place where money or valuable are kept. On the

Plan of St. Gall, it is consistently used in the sense of "store" or "supply

room."

SOUTH RANGE

In both the Plan of St. Gall and Cluny II the refectory

formed the principal mass of the south range, although at

Cluny the refectory was apparently a building of one storey.

It is 90 feet long, 25 feet wide, and 23 feet high. At Cluny

as on the Plan, the monks' kitchen (coquina regularis) lies

at the western end of the refectory in the corner between

refectory and cellar; but at Cluny there is also a kitchen

for laymen (coquina laicorum) not found on the Plan of

St. Gall. The dimensions of the two kitchens of Cluny

are the same, 25 feet by 30 feet. Since the Farfa description

of the house for noblemen and of the hospice for paupers

does not include any reference to kitchens, the coquina

laicorum may represent a consolidation of the formerly

autonomous kitchens of these two houses.[59]

The dimensions of the calefactory at Cluny indicate that

it was part of the south range. It has the same width as the

refectory, 25 feet, distinctly narrower than the buildings

of the dormitory range, which are 34 feet wide. The sequence

of the account suggests that the calefactory was at

the eastern end of the south range. This is a solution

different from that of the Plan of St. Gall, but at the same

time, the position of the calefactory at Cluny next to the

east range might suggest a development from its earlier

position under the dormitory in the east range on the Plan

of St. Gall.[60]

On the Plan of St. Gall both guest houses had not only their own

kitchens, but also their own bake and brew houses. See above, pp. 151153

and p. 165.

A pantry shown in Conant's plan between the refectory and the

kitchen in the south range seems to be based only on the dimensions of

the south range in the 1700-1710 plan. It is not indicated in the Farfa

text or Bernard's Ordo Cluniacensis, nor as far as I know, in any other

text.

WEST RANGE

At Cluny II, as on the Plan of St. Gall, the cellar (cellarium)

forms the principal building of the west range. It is 70 feet

long and 60 feet wide. Next to it lies a long and narrow

room which the Farfa text designates "aelemosynarum."

This room is 10 feet wide and 60 feet long; its name suggests

that it served as an area in which the almoner administered

to the needs of transient paupers. An inscription on the

Plan of St. Gall indicates that a room of similar shape and

nearly the same dimensions (15 feet by 47½ feet) performed

the triple function of serving as "an exit and entrance to

the cloister," as a Parlor "where the monks could converse

with guests" and as "the place where the feet [of the

visiting pilgrims] were washed" (exitus & introitus ante

claustrū ad colloquendum cum hospitibus & ad mandatū faci-

endū).[61]

A passage in chapter 46 of book II of the Customs

of Farfa reveals that it was in connection with the ritual of

the mandatum that the visiting paupers received their customary

ration of wine and bread (justitiam vini et libram

panis);[62]

and in a complete description of this ritual

the place where the paupers' feet are washed, is "in the

cloister to the side of the church" (in claustro juxta eccles-

iam)[63] which indicates that the eleemosynarium at Cluny was

located in the same relative position as the Parlor on the

Plan of St. Gall, and also served some of the same

functions.[64]

A parlor or auditorium is not mentioned in the Farfa

text, but appears in the two passages of the Ordo Cluniacensis,

written around 1086. In one of these the claustral

prior is admonished to "go through the whole cloister

beginning at the door of the auditorium, carefully checking

that the eleemosynarium is closed and locked" (Claustrum

incipiens ad ostium auditorii, sollicite observans quatenus

Eleemosynaria sit clausa et obserata).[65]

In the other, the

door of the eleemosynarium is mentioned next to "that other

door through which those who come from outside enter

the cloister" (ad ostium . . . Elemosynariae, et ad illud, per

quod de foris venientium est ingressus in claustrum.[66]

Both

passages suggest that auditorium and eleemosynarium were

two different areas. Architecturally this could have been

accomplished in two ways: either by relegating the function

of the parlor to a separate space, or by dividing the

oblong eleemosynarium internally into two areas accessible

by separate doors, one used as parlor, or auditorium, for

the reception of guests, the other for the washing of the

feet and the distribution of alms. In the former case one

would have to assume a separate room immediately to the

north of the eleemosynarium, perhaps in the court around

the galilee where Conant indicates a room for the Porter.

Ibid., Book I, chap. 54; ed. Albers, Cons. mon., I, 1900, 49; in

locum quo constitutum est, videlicet in claustro juxta ecclesiam deducat

pauperes ad sedendum.

VI.2.3

LAYOUT OF THE

EXTRA-CLAUSTRAL BUILDINGS

As on the Plan, the infirmary lies east of the church, the

houses for the guests to the west and northwest, and the

houses of the workmen to the south of the cloister.

AREA EAST OF THE CONVENTUAL BUILDINGS

In Cluny, as on the Plan of St. Gall, this tract contains the

monk's cemetery as well as the monks' infirmary. The

infirmary itself consists of four rooms, each 27 feet wide

and 23 feet long plus two additional rooms a little smaller

than the others. In one of these the sick brothers came to

wash their feet on Saturdays; in the other, attending

servants cleaned the pans and all the other utensils of the

sick brothers. The Farfa text does not refer to an infirmary

chapel; however, a chapel 45 feet long, 20 feet wide, and

23 feet high (oratorium sanctae Mariae) which could have

served this function is mentioned immediately before the

infirmary in the text. There is no further evidence to either

confirm or disprove this assumption.

In departure from the layout shown in the eastern tract

of the Plan of St. Gall, the novitiate has been separated

from the infirmary and moved to a site south of the east

range. As on the Plan, however, the novitiate may still

have been arranged peripherally around a cloister yard, as

Conant suggests in his latest plan. The Farfa text describes

it as composed of four parts: "In the first they meditate;

in the second they eat; in the third they sleep; in the fourth

there is a latrine on the side" (prima ut meditent, in secunda

reficiant, in tertia dormiant, in quarta latrina ex latere).

AREA SOUTH OF THE CONVENTUAL COMPLEX

Again, there are striking similarities between the Plan of

St. Gall and Cluny II. The bakery (pistrinum) lies to the

south of the monks' kitchen. The dimensions, including

the bulk of a tower that stands at the head of the bakery,

are listed as 20 feet by 70 feet. As on the Plan, the work and

living quarters for the workmen and craftsmen are arranged

along the southern edge of the monastery to the north of

the bakery. They are accommodated in a building (domus)

125 feet long and 25 feet wide.[67]

The goldsmiths, jewelers

or glaziers (aurifices, vel inclusores, seu vitrei magistri) had

their own cell, the dimensions of which are not listed in the

Farfa text. The principal house for workmen does not

include facilities for tailors and shoemakers. Their workshops

are located north of the cloister. This arrangement

differs distinctly from that on the Plan of St. Gall.

The Farfa text refers to this house simply as domus. It does not

state explicitly that this is the house for the workmen. The function of a

house of these dimensions and at this location, however, could not be

interpreted in any other manner.

AREA NORTH OF THE CLOISTER

The workshop for tailors and shoemakers (sartores atque

sutores) occupied a building 45 feet long and 30 feet wide

which extended clear to the sacristy on the north side of

the church. The sacristy is 58 feet long and has at its head

a tower (turris). Alfred Clapham proposed that the sacristy

and the house for the tailors and shoemakers might have

been installed in the masonry of the church of Cluny I,

the western half being converted into the workshop, the

eastern half into the sacristy.[68]

—a hypothesis that Conant

finds plausible.[69]

On the Plan of St. Gall this was the site

for the Abbot's House. A house for the abbot is not mentioned

at any place in the Farfa description.

The absence of a house for the abbot seems due to a

change in the rules concerning the abbot's sleeping accommodations.

The Customs of Udalric, written about 1085,

specifically state that the bed of the abbot was located in

the middle of the monks' dormitory and that it was the

abbot who gave the signal to get up in the morning: In

medio dormitorii est lectus eius prope murum; sonitum ipse

facit quo fratres diluculo ad surgendum excitantur.[70]

Since

the Farfa text fails to mention an abbot's house, this

practice must already have been in effect during the

abbacy of Odilo (995-1049). The beginnings of this development

can be observed in the tenth century monasteries of

Moyen Moutier and Leittlich. In each of these monasteries

the abbot's house was attached to the monks' cloister. To

eliminate the abbot's house entirely, thus to draw him

bodily into the community of sleeping monks, was the

ultimate step. It was the enforcement of a policy proposed

as early as 816 at the synod of Aachen, but revoked at the

synod of 817.[71]

Consuetudines Cluniacenses collectore Udalrico, Book III, chap. 2,

"De domno abbate," cf. Migne, Patr. Lat. CXLIX, 1882, cols. 733-34.

See the discussion of the legislative conflicts concerning the abbot's

right to live and eat in his own house; see I, 323-24.

AREA WEST OF THE CONVENTUAL COMPLEX

The Farfa text is quite explicit concerning the location and

use of the buildings which lie to the west of the church and

near the gate of the monastery. Again, the analogies with

the Plan of St. Gall are striking. Both on the Plan and at

Cluny this is the location of the houses in which the

monastery's visitors are received. On the Plan of St. Gall

these consisted of a House for Distinguished Guests, a

House for the Vassals and Knights who travel in the

Emperor's Following, a House for Visiting Servants, and

the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers.[72]

The monastery of

Cluny, according to the Farfa text, provides for a house with

bedding and eating space for forty noblemen and thirty

noblewomen, a house for the horses of the visiting noblemen,

and a house for pilgrims and paupers. The relative

location of these facilities, in both instances, appears to be

the same.

The house for the forty noblemen and the thirty noblewomen

at Cluny has been discussed in detail in a preceding

chapter.[73]

It belongs to the same building tradition as the

House for Horses and Oxen on the Plan of St. Gall, and its

two privies, which accommodated seventy toilet seats, forty

for men and thirty for women, reflect the highest standard

of medieval sanitation.[74]

The house for the horses and servants who travel in the

following of the distinguished guests extends from the

north gate to the south gate. It is 25 feet wide and has an

impressive length of 280 feet. The ground floor accommodates

the horses of the traveling guests and for that purpose

is divided into stalls (per mansiunculas partitas). Above the

stable there is a sunroom (solarium) where the servants

eat and sleep. This room is furnished with at least two

ranges of tables 80 feet long and 4 feet wide.[75]

The dimensions of the house for pilgrims and paupers

are not listed in the Farfa text. The building is simply

referred to as "the place where those can come together who

ride without squires and there receive from the almsbrother

sufficient charity in the form of food and drink" (locus . . .

ubi conveniant omnes illi homines, qui absque equitibus

deveniunt, et caritatem ex cibo atque potum . . . ibi recepiant

ab elemosynario fratre). The text tells us that it lies at the

head of the house for horses and servants, but does not

reveal whether this means to the south or north of it.

Conant placed it as the northern end of the stables. The

relative location of these facilities for guests, consequently,

appears to be like that on the Plan of St. Gall.

The Farfa text says nothing about any houses for livestock

and their keepers but the topography allows for a

forecourt of considerable dimensions precisely at the place

where one should expect them in the light of the Plan of

St. Gall.

Conant assigned this solarium to the monastery's lay brothers.

This is not implied in the Farfa text and is incompatible with the studies

of Kassius Hallinger, which indicate that the Cluniacs did not adopt the

lay brothers institution before the last decade of the eleventh century

(Hallinger, 1956, 14ff). The Farfa text only states that "servants" and

"excess guests that could not receive their meals in the house for the

visiting noblemen" (famuli . . . et quotquot ex adventantibus non possunt

reficere ad illam mansionem) should sleep and eat in the solarium above the

stable. The term famuli could refer to both the servants of the visiting

noblemen or visiting servants from the monastery's outlying estates.

It is likely, however, that those of the guests were intended. The servants

of the noble guests would then be lodged near the horses of their company,

as the travelers on the Plan of St. Gall were with theirs, and the

house for the nobles' retinue would be located near to their guest house,

as on the Plan. Each noble guest must have had at least two servants, so

housing for at least 140 servants would have been necessary. This was

probably the function of the room above the stables, since it provides a

large area and since the Farfa text specifies that it housed the guests

whom the palatium would not accommodate, as well as the famuli,

Furthermore, no other housing is provided for the retainers of the noble

guests.

IRREGULAR SHAPE OF ODILO'S CLOISTER YARD

The original concept of the Plan of St. Gall was that the

Church should be 80 feet wide and 300 feet long, but an

explanatory title inscribed in the longitudinal axis of the

Church directs that in actual construction it should be

reduced to 200 feet.[76]

The church of Cluny II, built by

Abbot Mayeul between 965 and 981, was only 140 feet

long (Ecclesia longitudinis CXL pedes).[77]

Conant believes that the timbered houses in which Abbot

Mayeul lodged the monks of Cluny lay further inward than

Odilo's conventual buildings, and that when Odilo constructed

the new masonry ranges he located them outside

and around the original structures.[78]

If this assumption is

correct, the old cloister yard of Cluny would have been

considerably smaller than the cloister yard of the Plan of

St. Gall (only about 75 feet square, as compared to the 100

by 102½ feet of the Plan or the 100 by 100 feet stipulated

original dormitory of the monks indeed have been located

inside of Odilo's masonry ranges, the original dormitory

of Cluny would have been in axial prolongation of the

transept of Mayeul's church, i.e., in the same relative

position in which it is shown on the Plan of St. Gall. Moving

his claustral ranges further out, Odilo would have

brought the cloister yard of Cluny back to the dimensional

standards set by the Plan of St. Gall but at the same time

would have created an irregularly shaped cloister yard, in

which the east range was separated from the transept. This

solution had no lasting effect on later monastic planning.[80]

It may very well have been the outcome of special local

conditions, namely the inordinate smallness of Mayeul's

church and original cloister which could only be overcome

by disconnecting dormitory and transept.[81]

Conant's arrangement also depends on the 1700-1710 plan of

Cluny (now in the Musée Ochier).

If the west range of Cluny II remained in the position in which

Conant shows it, and the east range were aligned with the transept,

the cloister yard would still be in line with the standard set on the Plan

of St. Gall. Nevertheless, if the east range is placed to the east of the

transept, it does account for a passage in the Farfa text which states that

the chapter house, which was located at the northernmost end of the

dormitory range, had "four windows on the east and three on the north"

(ad oriente fenestrae IIIIor; contra septemtrionem tres). In order to accommodate

three windows, the north wall of the dormitory range would