The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. | V. 12 |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 12

HOUSE OF THE GARDENER & THE

MONKS' VEGETABLE GARDEN

V.12.1

THE GARDENER'S RANK

Since the monks lived primarily on a vegetable diet, the

management of the monastic gardens was a responsibility

of prime importance. The official in charge of this task was

the Gardener (hortolanus), often not a monk but a layman.

On the Plan of St. Gall he is provided with his own house.

His high position in the monastic community is reflected by

the fact that within this house he occupies an aisle all by

himself, and, more significantly, that this part of the house

is equipped with a corner fireplace, a privilege not accorded

to any other person in the monastery's agricultural sector.

The Gardener's House lies in the eastern tract of the

monastery next to the Cemetery, at the head of the Monks'

Vegetable Garden. Together with the latter it occupies a

plot of land 125 feet long and 52½ feet wide.

V.12.2

HOUSE OF THE GARDENER & HIS CREW

The House of the Gardener (fig. 426) measures 35 feet by

52½ feet. It consists of "the house itself" (ipsa domus), i.e.,

the common living room with its central fireplace[439]

and three

aisles attached to it, one to the east, one to the north, and

one to the south. The west wall of the center room remains

exposed and contains the principal entrance. The southern

aisle of the house serves as "dwelling of the gardener"

(mansio hortolani). The eastern aisle is divided into two

rooms, which are designated as "sleeping quarters for the

servants" (cubilia famulorum). They are separated from one

another by a vestibule which gives access to the Garden.

The northern aisle of the house is "a storage place for the

garden tools and for the vegetable seeds" (hic ferram̄ta

reseruant' & seminaria olerū).

Abbot Adalhard in his manual on the economic management

of the monastery of Corbie gives us an account of the

kind of tools we may expect to find in this room; he also

tells us by whom they are supplied and kept in repair:

The gardener . . . ought to receive all iron tools from the chamberlain,

who should supervise the smiths according to the custom of the

community. If any of the tools should be broken, let the gardener

show them to the chamberlain and let him have them repaired or

give out another metal appliance and take in the broken one.

Furthermore, those tools must then be repaired by the chamberlain

in whatever way may be necessary. And for cultivating the field or

for carrying out any other needs, let each one have six hoes [fussorios],

two spades [bessos], three straight axes [secures], an adze

[dolatorium], two augers [taratra] large and small, one chisel

[scalprum], one gulbium (unidentifiable), two sickles [falcilia], one

scythe [falcem], two trunci (possibly "handles" for axes and

scythes), one coulter [cultrum], one scerum (possibly "shears"),

and other instruments kept in the chamberlain's office, as winnowing

fans [uanni], casting shovels [banstae], or other things of this

sort.

In our reconstruction of the Gardener's House (fig. 427,

A-F) we have kept the roof line of the peripheral spaces on

the same level, which leaves the upper parts of the walls on

the two narrow sides of the center space exposed as timber

framed gables. Another alternative would have been to lead

the rafters on the two narrow sides of the house up to a

cross piece near the ridge of the main roof, as we have done

in all of the larger guest and service buildings where hipped

roofs have clear constructional advantages. In small houses,

such as the Gardener's House, the solution here suggested

might have been the simpler one, provided that the rafters

of the main roof were protected against longitudinal displacement

by some secondary provision, such as a center

purlin framed into collar pieces. This is a very common

stabilizing device in English roof construction of the thirteenth

and fourteenth centuries (a typical example is St.

Mary's Hospital in Chichester, above fig. 342). Whether

we can expect it to have been used on the continent in

Carolingian times is another question.

With regard to the meaning of ipsa domus, see I, 77-78. Keller's

interpretation (1844, 31; followed by Willis, 1848, 114; and Leclercq, in

Cabrol-Leclercq, 1924, col. 104) of this room as a "Hof, in dessen Mitte

sich ein kleines Gebäude, domus ipsa, befindet" rests on a misinterpretation

of the term domus, and its mistaken identification with the fireplace

instead of the room that surrounds the hearth.

V.12.3

THE MONKS' VEGETABLE GARDEN

The Monks' Vegetable Garden (HORTUS) lies to the east

of the Gardener's House and to the south of the shadowing

fruit trees of the Cemetery (fig. 426). It covers a rectangular

plot of land 52½ feet wide and 82½ feet long, and is entirely

surrounded by a wall or a fence, having a single entrance

at the side which faces the Gardener's House. Internally the

garden is divided into two rows of planting beds separated

from one another by a central path that carries the inscription

"Here the planted vegetables flourish in beauty" (Hic

plantata holerum pulchre nascentia uernant"). There are nine

planting beds in each row. They are separated from one another

by eight crosswalks, and from the surrounding wall or

fence, by a continuous peripheral walk, all of the same width.

We have to imagine the planting surface of these beds as

being raised above the level of the walks and framed in by

planks held in place by stakes. This is suggested by a passage

in Walahfrid Strabo's Hortulus[440]

as well as a variety of

paintings and drawings of medieval gardens, such as the

famous hortus conclusus (Paradiesgärtlein) in the Städelsches

Kunstinstitut of Frankfurt, painted around 1410 by an

unknown Rhenish master;[441]

the charming illustrations of

the labors of the month of April in the Heures de Turin (fig.

428), or the illumination of a garden with clipped trees in

the Grimani Breviary (fig. 429).[442]

2 Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 4, ed. Semmler, in Corp. Cons.

Mon., I, 1963, 381. For difficult and unexplainable terms, see translation

and annotations to this passage, III, 108f and notes 76-82.

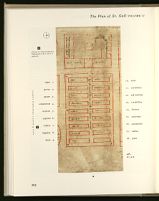

426. PLAN

426.X PLAN OF ST. GALL.

HOUSE OF THE GARDENER AND HIS CREW AND MONKS' VEGETABLE GARDEN

The position of the Monks' Vegetable Garden between the Orchard (y) and the poultry runs (21, 23) as well as its proximity to the Monks'

Latrine (4) demonstrates the awareness for functional inter-relationships characterizing the intelligence of those who designed the Plan. Both

Orchard and Garden come under the care of the Gardener. The Garden would have drawn the most effective fertilizer from the nitrogen-rich

droppings of the nearby fowl yards; grain feed for chickens and geese (the Granary is in close proximity) could be augmented by trimmings from

the vegetables. However, the most important source for fertilizer might have been the Monks' Privy, if the waste there was not swept away

through water channels but (as seems more reasonable to assume) was gathered in settling tanks.

The garden plots were devoted largely to what we today consider to be seasonings or spices; with root crops in need of more space than that

available within the monastic compound, and therefore grown on land outside the walls, the produce of the garden could be largely devoted to

crops for enhancing the flavors of the monks' heavily vegetarian diet.

Each bed of the Monks' Vegetable Garden is used for

the cultivation of a specific type of plant, the name of which

is entered by the hand of the second scribe in the pale ink

that characterizes his writing.[443]

Read from top to bottom in

the sequence in which they were written they are:

| 1. | cepas | onion (allium cepas L.)[444] |

| 2. | porros | leek (allium porrum L.) |

| 3. | apium | celery (apium graveolens L.) |

| 4. | coliandrum | coriander (coriandrum sativum L.) |

| 5. | an&um | dill (anetum graveolens L.) |

| 6. | papaver | poppy (papaver somniferum L.) |

| 7. | radices | radish (raphanus sativus L.) |

| 8. | magones | poppy[445] (papaver . . . L.) |

| 9. | betas | chard (beta vulgaris or beta cicla L.) |

| 10. | alias | garlic (allium sativum L.) |

| 11. | ascolonias | shallot (allium ascolonicum L.) |

| 12. | p&rosilium | parsley (apium petrosilium L.) |

| 13. | cerefolium | chervil (anthriscus cerefolium Hofmann) |

| 14. | lactuca | lettuce (lactuca scariola L.) |

| 15. | sataregia | pepperwort (satureia hortensis L.) |

| 16. | pastinchus | parsnip (pastinaca sativa L.) |

| 17. | caulas | cabbage (brassica oleracea L.) |

| 18. | gitto | fennel (nigella satira L.) |

Areola et lignis ne diffluat obsita quadris

Altius a plano modicum resupina levatur.

Then the garden patch is baked with the gust of the South wind and the heat

of the sun, and the flat-planted bed, lest it slide away, is raised a little higher than

the flat ground with wooden squares.

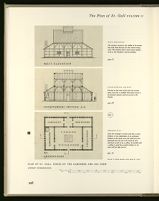

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE OF THE GARDENER AND HIS CREW

427.C WEST ELEVATION

The entrance, located in the middle of the western

long wall, leads directly into the common living

room. The northern lean-to with corner fireplace

serves as the Gardener's private dwelling.

427.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

The door in the center leads from the common

living room into a vestibule which gives access to

the servants' quarters and has an exit to the

Garden.

427.A GROUND PLAN

Since the Gardener's private room had a corner

fireplace, it was independent of the communal

fireplace in the living room and could have been

separated from the rest of the house by wall

partitions as well as by a ceiling. If provided with

a ceiling it would have needed windows in the

outer wall for light and air.

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

427.F NORTH ELEVATION

The Gardener's private dwelling is a lean-to

attached to the northern end of the communal

living room. Whether its roof ended on the level

here shown or reached up to the ridge in the form

of a hip, is impossible to ascertain.

427.E SOUTH ELEVATION

The southern lean-to serves as tool shed. It

received its light and warmth (if any) from the

fireplace and louver in the communal living room.

427.D TRANSVERSE SECTION

The door to the left connects the living room with

the Gardener's private dwelling. The door to the

right leads from a vestibule, located in the middle

of the eastern aisle of the house into one of the

two bedrooms of the servants.

The layout of the Gardener's House is identical with that of the House for Cows and Cowherds (fig. 438) and the House for Foaling Mares and

their Keepers. (fig. 487). In all of these the common living room with the traditional open fireplace is surrounded with subsidiary outer spaces

on three sides only. The entrance is in the middle of the wall that lacks an aisle. The House of the Physicians (fig. 410) belongs to the same

family of structures.

428. HEURES DE TURIN (CA. 1390). LABORS OF THE MONTH OF APRIL

(FORMERLY) TURIN, BIBLIOTECA NAZIONALE, MS. K. IV. 29, FOL. 4, DETAIL

[after Durrieu, 1902, pl. IV]

The scene showing the seeding of staked and raised garden beds is one of twelve calendar pictures forming part of a manuscript begun at the

end of the fourteenth century for the Duc de Berry, but never finished. Before 1413 the manuscript was held by Robinet d'Estampes, keeper

of de Berry's jewels. Other parts of the same manuscript are in the Museo Civico of Turin, and the Bibliotheque Nationale and the Louvre,

Paris. The fragment shown above perished in a fire that destroyed the whole library in 1904; fortunately, Durrieu had published it two years

earlier.

Sörrensen points out that most of these plants, although

not native to the north, are still today the main stock of a

well-planned vegetable garden.[446]

Their choice discloses that

this garden was primarily a kitchen garden. It does not

include such crops as beans, lentils, beets, carrots, and the

bulkier cabbage varieties whose cultivation required larger

plots. These heavier crops must have been raised in the

outlying fields.

In a monastery like the one represented on the Plan of

St. Gall, around 250 men had to be fed each day.[447]

The

Abbey of Corbie, which had to feed over 400 persons daily,

maintained four gardens outside the monastery walls under

the direction of four gardeners (hortolani) who were assisted

by eight prebends (prouendarii) and a large number of

workmen from the neighboring villae whose exclusive task

it was, between April 15 and October 15, to hoe and weed

the land as well as to repair its huts and fences.[448]

This and

the fact that each gardener had at his disposal an ox and

a plow suggests that the gardens outside were large.[449]

In addition to the crops harvested from the gardens and

fields managed by the monks themselves, there were those

which the monastery received as tithes from its leased

possessions. Accounts of the Abbey of St. Gall tell us of

deliveries of beans from its lands at Gossau, Geberardiswiller,

Arnegg, Tiefenbach, and Opferdingen, as well as of

large shipments of leek, such as the "thirty loads of leek"

(XXX pondera porri) which were annually transported to

St. Gall from Hohenweiler in the Voralberg or Scheidegg

in Bavaria.[450]

Lastly, the local produce was enriched by

staples imported from the south, such as olives, lemons,

dates, raisins, pomegranates, and chestnuts. Most of these

latter goods the Abbey of St. Gall imported from the

monastery of Bobbio in Lombardy, with which it entertained

a lively trade.[451]

GRIMANI BREVIARY (CA. 1490). GARDEN WITH TOPIARY TREES

429.

This masterpiece of illumination, of

uncertain authorship, provenance, and

date, was made at the period of

transition between the Middle Ages

and the Renaissance. The style of the

manuscript, in which many masters

collaborated (the majority Flemish, a

few perhaps French), suggests a date

between 1490 and 1510, probably

nearer the latter according to David

Diringer (The Illuminated Book;

New York-Washington, rev. ed.

1967, p. 455). The manuscript, one

of the largest in existence, is composed

of 832 leaves measuring 22 × 28 cm.

It was published in a facsimile edition

of thirteen volumes (ed. Scato de

Vries) in 1903-1908.

VENICE, BIBLIOTECA DI SAN MARCO. FOL. 613

[after Morpurgo and de Vries, I, 1903-1908, pl. 1165]

A typical late medieval "Ziergarten" (decorative pleasure garden) shows planting beds raised by means of staked boards above the level of

the walks, as in Walahfrid Strabo's garden (above, p. 183). The beds are laid out in two rows and are framed by a peripheral row of bordering

beds, as in the Medicinal Herb Garden (figs. 414-415).

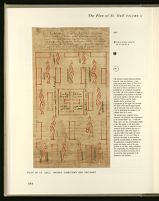

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' CEMETERY AND ORCHARD

430.

The cemetery contains thirteen planting

areas for trees and fourteen (= twice

seven) burial plots. Seven of them lie to

the east of the great cross in the center,

and seven of them at and below it. It is

probably not an accidental arrangement

but rather one of the countless examples of

preoccupation of the drafters of the Plan

with sacred numbers. Thirteen evokes the

memory of Christ and the twelve

Apostles and in particular their

congregation at the supper that preceded

His death. (The tendril-shaped symbol

used to locate the trees of the orchard is

a key to identifying the designer of the

original Plan; see I, 27ff).

The number seven, Augustus writes,

expressed "the wholeness and completeness

of all created things" (cf. I, 118ff, and

Horn, 1975, 351-90). The modular scheme

of the Plan applies to the burial plots:

their width, 6¼ feet, is composed of two

standard 2½-foot modules plus one 1¼-

foot submodule, while their length, at

17½ feet, reflects once again the sacred

number seven: 7 × 2½ = 17½. Thus, in

each plot the bodies of seven brothers

could be accommodated, in keeping with

the application of standard modules to

achieve the human scale of the other

facilities of the Plan. And as elsewhere,

this compounding and multiplication of

sevens can hardly be fortuitous, but on

the contrary, quite purposeful in the

planning of the Cemetery.

Cf. above p. 181. Walahfrid (Hortulus, ed. Dümmler, in Mon.

Germ. Hist., Poetae Latini Aevi Carolini, II, 1884, 337, vss. 46-49;

ed. Näf and Gabathuler, 1957, vss. 46-49) tells us how he protects the

planting beds in his garden in this manner:

For the Heures de Turin, see Durrieu, 1902, Pl. IV. For the Grimani

Breviary, fol. 613, see Morpurgo and de Vries, I, 1903-8, pl. 1165.

Another fine example is the illumination of the month of March in the

Breviary of the Musée Mayer van den Bergh at Antwerp, fol. 2v (see

Gaspar, 1932, pl. III).

The modern Latin plant names listed in parentheses are taken from

Wolfgang Sörrensen's article on the gardens and plants of the Plan.

To Sörrensen we owe much other vital information on this subject; see

Sörrensen in Studien, 1962.

The fact that poppy appears twice is bewildering. Sörrensen (ibid.,

210-11) feels certain that magones is poppy, but which variety of poppy

remains uncertain.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 4, ed. Semmler, in Corp. Cons.

Mon., I, 1963, 380-82; and translation, III, 108-109.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||