The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. | V. 17 |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 17

FACILITIES FOR THE RAISING

OF POULTRY AND LIVESTOCK

V.17.1

ANIMAL HUSBANDRY:

AN INTRINSIC

PART OF THE MONASTIC ECONOMY

The presence on the Plan of St. Gall of a vast array of

houses for livestock and poultry and their keepers may at

first seem puzzling in view of the monks' essentially vegetarian

diet. It becomes a less surprising phenomenon,

however, when one considers that, although meat was categorically

interdicted to the monks themselves by a rule

that left no margin for ambiguity, it was permitted to

the serfs and workmen, who outnumbered the monks, and

even to the monks themselves in times of sickness and

during the period of bloodletting.[594]

But there are other

reasons, and probably more important ones, why the raising

of livestock was a necessary part of the monastic

economy. Animals were needed for hauling and riding.

Without horses and oxen harnessed to plows and carts,

the serfs could neither have tilled the soil nor brought in

the harvest. Saddle horses were an indispensable means of

transportation for the abbot or any other monastic official

whose business took him onto the monastery's outlying

estates. Horses had to be raised for the king as an annual

contribution to the common defense, and horses had to be

kept in readiness for the armed men whom the monastery

was required to dispatch to the king's army in times of

war.[595]

Cows, sheep, goats, and pigs were slaughtered for their

meat, and from the Liber benedictionum of Ekkehart we

learn that the cuts of meat from these animals were as

cherished in his day on the tables of those who could

afford them as they are today.[596]

But cows, goats, and sheep

also produced milk, a more important product, because it

was used to make cheese—a staple in everyone's diet.

Sheep's wool was indispensable for making coats and

blankets. Leather was made from the hides of oxen. The

skin of the calf and the lamb yielded a commodity that was

of prime importance for the monastery's religious and

educational mission: parchment. The quill used in writing

the sacred texts came from the wings of geese.

The meat of poultry, as has already been pointed out,

was not subject to the same restrictions as the meat of

quadrupeds. The second synod of Aachen (817) granted

it to the monks for a period of eight days on each of the

great religious feasts of Christmas and Easter. Later the

number of days was reduced to four on each of these

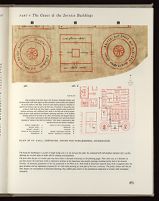

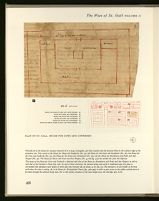

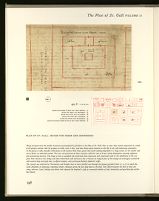

PLAN OF ST. GALL, HENHOUSE, HOUSE FOR FOWLKEEPERS, GOOSEHOUSE

466.

466.X

SITE PLAN

The proximity of the fowl runs to the Granary, Vegetable Garden, and

Orchard shows with what degree of skill convenience and necessity were planned

for by the makers of the Plan. Grain for feed could be gleaned or threshed at

need in the Granary and carried to the fowl runs. Proximity to the gardens was

a boon for both birds and their keepers—garden clippings might provide the

chickens and geese with additional food, while in the beds and orchard manure

from the pens could quickly be distributed, enhancing sanitation. In all facilities

housing animals on the Plan of St. Gall, the herdsmen and keepers lived in

close contact with beasts; while the fowlkeepers were spared the literal

necessity of "going to bed with the chickens," their house is separated by only

ten feet from the two poultry enclosures.

The house for fowlkeepers is 35 feet in length (ridge axis E to W) and 42½ feet wide. Its communal hall with fireplace measures 22½ × 35 feet,

allowing two 10-foot aisles at either side for sleeping accommodation.

The form that the pair of circular pens may have taken is discussed extensively on the following pages. Their sheer size, at a diameter of

42½ feet (across the outermost circle) is impressive evidence of the importance that poultry (perhaps including ducks) had in the monastic

economy. A monastery population of the size postulated on the Plan of St. Gall would in itself have required many birds to augment diet; the

guest facilities and lay dependents proposed for St. Gall made planning for fowl pens of this size a necessity. The poultry houses and that for

their keepers are masterpieces of functional planning; they exhibit great charm in the symmetrical composition of circular with rectangular

structures.

467. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). GOOSEHERD

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 169v (detail)

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

A goose and five goslings are threatened by a hawk; the gooseherd waves his hood and staff at it to drive it off. Geese were not only useful as

food, but kept vermin and garden pest populations down; their raucous and hostile response to strangers, well known since the early days of

Rome, may have added to their utility in the life of a large monastic complex.

prohibited, hens were of vital importance for their capacity

to produce eggs—a year round staple in the monastic diet

and one of its most important sources of protein. For egg

production alone, the raising of poultry was bound to be

one of the most important aspects of monastic animal

husbandry, and the polyptichs and household accounts from

medieval abbeys abound with records of supplementary

deliveries of eggs, chickens, and hens (ova, pulli et gallinae)

from the abbey's outlying farms.[598]

Lastly we must not overlook the fact that these animals

provided the only good fertilizer that was known to the

medieval agriculturalist and one that made a vital contribution

to the enrichment of the community's crop and

harvest.

It becomes quite clear then, that despite the monks'

essentially vegetarian diet, the monastery as a self-sustaining

economic and agricultural entity could not forego

the need to raise livestock and poultry in quantities commensurate

with the number of men whom it had to clothe

and feed. In the spring, summer, and autumn the majority

of monastic animals were unquestionably put out to pasture.

For that reason, the houses for livestock and their

keepers shown on the Plan of St. Gall are likely to define

only that space which was needed to stable the animals

kept under roof and shelter during the harsh winter months

in order to insure the propagation of the species. The

costliness of stall feeding demanded that this be done with

discretion. A thirteenth-century directive recorded in the

cartulary of Gloucester Abbey rules that "no useless and

unfertile animals are to be wintered on hay and forage"

(quod nulla animalia inutilia et infructuosa hyementur ad

consumptionem foeni vel foragii) and the text makes it clear

that exceptions to this ruling should be made only with

regard to such useful and deserving animals as the plow

oxen and breeding cows (talia scilicet de quibus non credatur

posse nutriri aliquis bos utilis ad carucas vel vacca competens

ad armentum).[599]

The directive reflects a general condition

of medieval animal husbandry that pervaded all social

strata and the whole of medieval life, with only minor

variations on the highest levels.

The importance of animal husbandry is eloquently

attested by St. Fructuosus in the ninth chapter of his

Galician Rule. As noted in the translation by Barlow, this

chapter does not appear in the Fructuosan Rule for other

areas, presumably because (as Fructuosus acknowledges)

468. MEINDERT HOBBEMA

A FARM IN THE SUNLIGHT (1660-1670)

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON D.C.

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the National Gallery of Art]

any other land" and the monk in whose charge lay the

pasturing of livestock needed not only firm direction but

also moral support:

"Those who accept the charge of attending the livestock of the

monastery should show such concern for them that they will not

cause any harm to the crops, and they should be watched so carefully

and so astutely that they will not be devoured by wild beasts,

and they should be kept away from steep and rocky mountains and

inaccessible valleys, so that they will not slip over a precipice. But,

if any of the above-mentioned negligent deeds happens because of

inattention or lack of care on the part of the shepherds, they shall

straightway throw themselves at the feet of their elders and, as

though deploring great sins, shall for a considerable time suffer

penance worthy of such a fault. . . . The flocks are to be placed in

the charge of a monk who is well-proved, who was trained to this

sort of work while in the world, and who desires to guard the flocks

with such good intention that never the slightest complaint comes

from his lips. They may have younger ones assigned them by turns

to share their labor. They may have sufficient clothing and covering

for the feet. One monk, such as we have mentioned, shall be responsible

for this service, so as not to inconvenience all the monks

in the monastery. But since some who guard the flocks are accustomed

to complain and think they have no reward for such

service when they cannot be seen praying and working in the

congregation, let them harken to the words of the Rules of the

Fathers . . . recognizing the examples of the Fathers of old, for the

patriarchs tended flocks, and Peter performed the duties of a

fisherman, and Joseph the Just, to whom the Virgin Mary was

espoused, was a carpenter. Accordingly, they have no reason to

dislike the sheep which have been assigned to them, for they shall

reap not one but many rewards. Their young shall be refreshed,

their old shall be warmed, their captives redeemed, their guests and

strangers entertained. Besides, most monasteries would scarcely

have enough food for three months, if there existed only the daily

bread in this province, which requires more work on the soil than

any other land. Therefore, one who is assigned this task should

happily obey and should most firmly believe that his obedience

frees him from all danger and prepares him for a great reward

before God, just as the disobedient one suffers the loss of his

soul."[600]

The total area set aside for animal husbandry on the

Plan of St. Gall takes up more than one-fourth of the

monastery site. It accommodates six houses for the larger

breeds and two enclosures for poultry, as well as the living

rooms and bedrooms needed for their keepers. The stables

for the larger animals are concentrated in a large service

yard lying to the south and west of the claustrum; the

houses for the poultry are in the southeast corner of the

monastery site, between the vegetable garden and the

granary.

On St. Benedict concerning the consumption of meat, see above,

I, 277ff. This may be unequivocally inferred from the Administrative

Directives of Adalhard of Corbie, which regulate the distribution of meat

both to the serfs and to the guests of the monastery. See I, 305-306.

With regard to the relaxation of the general rules concerning meat

consumption during sickness and the time of bloodletting, see I, 275;

and above, p. 188.

Historia et Cartularium Monasterii S. Petri Gloucestriae, in Rerum

Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores, XXX:3, London, 1867, 215.

Cf. Hilton, 1966, 120-21.

St. Fructuosus, General Rule for Monasteries, Chapter 9, translated

by Claude W. Barlow in Iberian Fathers, vol. 2, 189-90, Washington,

D.C., 1969 (The Fathers of the Church, vol. 63). For the Latin text

see Sancti Fructuosi Bracarensis episcopi regula monastica communis, cap. IX,

in J. P. Migne, Patr. Lat. LXXXVII, Paris, 1863, cols. 1117-18. The

Common Rule of St. Fructuosus was written about A.D. 660 after he had

founded numerous monasteries in western Spain.

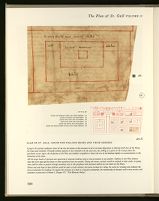

V.17.2

HOUSES FOR POULTRY & THEIR KEEPERS

The monastery's facilities for the raising of poultry consist

of a dwelling for the fowlkeepers and two circular enclosures—one

for hens, the other for geese. They lie in a plot

of land about 60 feet wide and 145 feet long.

HOUSE OF THE FOWLKEEPERS

The House of the Fowlkeepers (fig. 466) lies midway

between the Hen House and the Goose House. It is a

relatively small and simple house, 42½ feet wide and 35

feet long, consisting of a "common hall" (domus communis)

with a fireplace, and two aisles, one serving as "dwelling

the other as "dwelling for the keeper of the goose house"

(item custodis aucaru). The house is entered axially through

doors in its eastern and western gable walls, which assure

the shortest and most direct communication with the Hen

House and Goose House.

The House of the Fowlkeepers is the only example

among the Plan's guest and service buildings in which the

principal room of the house has aisles on only two sides

and is connected directly with the exterior by doors located

in the two gable walls. A fine pictorial record of this type

of house may be found in a painting by Meindert Hobbema

(fig. 468) entitled A Farm in the Sunlight. This small,

relatively modest farmhouse is aisled but has no lean-to's

on the gable side. A chimney in the ridge of the roof suggests

that it has a central fireplace. The entrances, as in the House

of the Fowlkeepers, are obviously in the longitudinal axis

of the building. The frame of timber supporting this roof

may have corresponded, beam by beam, to that of the

House of the Fowlkeepers. Our reconstructions (fig. 469)

are an attempt to interpret this system.

HENHOUSE AND GOOSE HOUSE

Layout and design

The Hen House and the Goose House lie on either side

of the House of the Fowlkeepers, one to the west, one to

the east (fig. 466). They are the same size and identical

in design. Each consists of three concentric circles, drawn

at diameters of 12½, 27½, and 42½ feet. The only entrance

to each is on the side facing the House of the Fowlkeepers.

The enclosures are identified by metric titles written in

capitalis rustica (a distinction not accorded to any other

building housing animals):

PULLORUM HIC CURA ET PERPES NUTRITIO CONSTAT

HERE IS ESTABLISHED THE CARE OF THE CHICKENS

AND THEIR CONTINUOUS NOURISHMENT

and:

ANSERIBUS LOCUS HIC PARITER MANET APTUS ALENDIS

THIS PLACE IS WELL FIT FOR THE SUSTENANCE OF GEESE

The intermediate bands are not provided with titles, and

the inner circle is decorated with an eight-lobed rosette—of

the same design and probably the same apotropaic purpose

as the corresponding symbol in the two church towers.

The interpretation of these two circular poultry houses

poses problems.

Classical, medieval, and modern parallels

I do not know of any classical prototypes. The Roman

hen and goose houses described by Columella and Varro

were buildings of rectangular shape.[601]

But the question

arises whether there may be some typological connection

between the hen and goose houses of the Plan of St. Gall

and the circular bird house which Varro built in his villa

at Casinum.[602]

There appear to be no medieval parallels,

unless a circular enclosure with two rectangular attachments

on the grounds of the tenth-century royal palace at Cheddar,

in Somerset, England (fig. 470)—which its excavator,

Philip Rahtz, interpreted as a mill with grain bin and

bakery—was in reality a chicken house. The light construction

of its walls, all braided in wattlework, may speak in

favor of such an assumption.[603]

In his model of 1877 Julius Lehmann reconstructed the

poultry houses of St. Gall in the image of a medieval dovecot

(fig. 267). He interpreted the outer circle as a wall, and

the area between this circle and the inner circle as an open

poultry run. Besides the fact that this interpretation completely

disregards the existence of an intermediate circle,

Lehmann's solution involves a conspicuous imbalance between

running and roosting space and would appear to

be incompatible with the functional perspicacity that the

author of the Plan exhibits in the handling of all other

details of this nature.

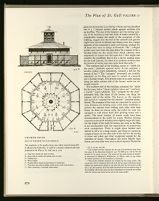

The clue to the riddle may be found in an octagonal

chicken house built in the nineteenth century by Freiherr

von Ulm-Erbach, and described in 1886 in Bruno Dürigen's

monumental work on poultry breeding (fig. 472).[604]

Dürigen referred to the design of this house as "a formerly

favored" but "now superannuated" form that had a long

tradition and was used in many zoological gardens because

of its specific suitability for exhibition purposes.[605]

The

house is 26 feet (8 meters) in diameter and 23 feet (7

meters) high. Like the poultry houses of the Plan, it has

three concentric strips of space and only one entrance. The

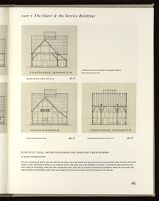

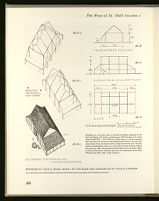

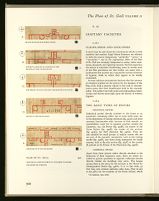

HOUSE OF THE FOWLKEEPERS

469.B TRANSVERSE SECTION

469.A GROUND PLAN

469.D LONGITUDINAL SECTION

469.C WEST ELEVATION

AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

Among the guest and service buildings of the Plan, this house is the sole example in which the communal inner hall is flanked by aisles only on

its two long sides. The hall is divided into three bays—a center bay 15 feet deep and two gable bays 10 feet deep. A division into four bays of

equal width would have brought the center truss into conflict with the fireplace and doors leading from hall into aisles. In all other respects our

reconstruction is modeled after the farmhouse in the Hobbema painting of fig. 468.

470. CHEDDAR, SOMERSET, ENGLAND

SAXON PALACE SITE, 10th CENTURY

[Redrawn from Rahtz, 1962/3, 62, fig. 24]

Of the two alternatives considered by Rahtz, the identification of this site as a

poultry house (rather than a corn mill) appears to be the more plausible, unless

it could be demonstrated that an animal-driven mill, common among the Romans

(cf. figs. 441-442), but subsquently used only when water power was lacking

(as during drought), would still have been operating in the 10th century in an

Anglo-Saxon palace. All available literary sources seem to offer evidence to the

contrary. Had the circular component of this structure housed a mill, it seems

likely that the supports of so heavy a mechanism would have left evidence more

tangible than that found on the site.

run for the chickens. The intermediate strip is roofed

over and serves as coop, leaving in the center a tower-like

projection, the raised roof of which admits air and light

through clerestory windows. The chickens are fed and

watered from this center space, and the house can be

heated by a stove set up in this area.

The portion serving as coop consists of a lower and an

upper tier, the lower being used for laying and brooding,

and the upper, for fattening.[606]

Both tiers have trap doors

toward the chicken run which can be closed at night, with

ladders enabling the birds to descend to the ground from

their roosting pens and to ascend again in the evening.

Freiherr Ulm-Erbach's chicken coop had a housing capacity,

on the lower tier alone, of 192 birds. The Hen House

of the Plan, which is practically identical in dimensions,

could have accommodated the same number—and if it

were meant to be a double-tier arrangement, twice that

number. For the geese and ducks (should anseres be a

generic term for both of these breeds) this figure would

have to be reduced by a ratio commensurate with their

larger size.

In Roman times, according to Columella,[607]

one laborer

was considered sufficient to care for 200 chickens. On the

Plan of St. Gall the keepers of the hen and goose houses

are referred to in the singular, but the rooms in which they

sleep are large enough to accommodate beds for three or

four additional hands. The raising of chickens is a year-round

operation; but geese generally mate in December,

so that goslings can be grazed in the open fields in the

spring, without supplementary feed and extra housing

(fig. 467). The guarding of these flocks would require

additional hands.

Columella, On Agriculture, Book VIII, chap. 3, ed. Ash-Forster-Heffner,

II, 1954, 331-37. Varro, On Agriculture, Book III, chap. 9,

ed. Hooper-Ash, I, 1936, 473-75. Cf. also Ghigi, 1939, 59ff, and 89ff.

Rahtz himself is reconsidering his original interpretation of this

installation (personal communication); see Rahtz, 1962-1963, 62.

This, at least, is the way the building was planned. In actuality, the

upper tier was modified, to the detriment of its function, because the

building site did not permit a structure of the height required by two

full stories.

Materials and location

I am inclined to believe that the poultry houses on the

Plan were meant to be masonry structures (fig. 473), not only

because circular walls are more readily built in stone than

in wood, but also because masonry makes more feasible

the construction of holes into which the birds may retreat

for laying and hatching. Columella rated laying-nests holed

into masonry superior to wicker baskets suspended in

front of the walls.[608]

It is likely that a wattlework fence was

intended for the outer fence that enclosed the poultry runs.

The siting of these houses is ideal, as the chickens and

geese are located near their two basic foods. The granary

lies on one side of the poultry enclosure, and the Monks'

Vegetable Garden on the other. The chickens would doubtless

have been eager to eat the weeds and scraps of vegetables,

after these had been cleaned and cropped for the

monks' table, as the gardeners were anxious to part with

them. And the Monks' Vegetable Garden provided a suitable

place to dispose of the birds' droppings when the

poultry houses were cleaned out.

GOSPELS OF ST. MEDARD OF SOISSONS (9TH CENT.) CANON ARCHES

471.A

471.B

PARIS, BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS. LAT. 8850, fol. 12v (detail)

Two cocks perch on slender columns that rise from the outer edges of the abaci of the two outer capitals of a canon arch; they are typical of

the classicizing style of manuscript painting cultivated in the Court School. For other manuscripts of the Court School see figures 18-23, and

183-184 in Volume I.

V.17.3

HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN

AND THEIR KEEPERS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Ista bubues[609] conseruandis domus atq. caballis

This house is for the care of the horses and oxen

The House for Horses and Oxen and Their Keepers

lies west of the House of the Coopers and Wheelwrights

and south of the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers (fig. 9).

Measuring 145 feet in length and 37½ feet in width, it is

the largest of the buildings housing livestock. It contains

in its center the "the hall for the oxherds and horse grooms"

(domus bubulcorum & equos seruantium). This is a large

square room with an open fireplace in the center and

benches all around its four walls, another unique and

distinguishing feature among the buildings used for livestock

and their attendants. The fireplace has unusually

CHICKEN HOUSE

472.B ELEVATION

472.A PLAN

BUILT BY FREIHERR VON ULM-EHRBACH

The complexity of this poultry house may reflect centuries-long skills

in efficient fowl husbandry; it could be a structure identical with that

proposed for the Plan of St. Gall. (see p. 272).

into it a

on the Plan. The size of the fireplace and the seating capacity

of the benches in this hall, both of which exceed by a

considerable margin the needs of the occupants of this

building, suggest that the hall of the oxherds and grooms

might have served as kitchen and dining room for a larger

segment of the monastery's serfs and laymen, perhaps for

all those who were in charge of livestock. The

symbol may have been the sign either for a hearth or for a

wooden frame for the cranes from which caldrons were

suspended on chains over the open fire.[610] One might also

consider the possibility that it was a rig for making shoes

for the draft animals, but there is no positive evidence that

the hooves of horses and oxen were shod this early.[611]

The northern hall of the building serves as "stable for

the mares" (stabulum equarum infra). It has overhead, a

wooden ceiling (supra tabulatum), certainly a loft for the

storage of hay.[612]

The "mangers" (praesepia) are carefully

delineated on the Plan and seem to consist of a hayrack

and a feeding trough. The grooms slept in an aisle running

along the entire eastern side of the horses' stable (ad hoc

seruitiū mansio).

The southern half of the building contained the "stable

for the oxen, below" (boum stabulum infra) and "overhead,

a hayloft" (supra tabulatū). The "mangers for the oxen"

(praesepia boū), like those of the horses, ran along the

western wall of the stable. The lean-to on the opposite

side served as "quarters for the oxherds" (conclaue assecularum).

The mangers of the oxen are separated by means of

cross divisions into feeding areas 5 feet wide, doubtless to

prevent the animals from striking each other with their

horns. As there are eleven stalls, the stable for oxen was

equipped to stall eleven head (five plowing teams and a

spare). The same number of horses could have been

accommodated in the stable for mares. Modern farming

manuals recommend standing areas slightly larger (6½ feet),

but the length of the stalls for horses and oxen on the Plan

is not incompatible with the requirements of present-day

stock management. There is ample space behind each

animal to serve as a dung trench, and there is a generous

margin of space on the other side of the stall for the storing

of plows and yokes and other equipment needed for the

operation of teams. Throughout the entire Middle Ages

horses and oxen alike were used as draft animals. Numerous

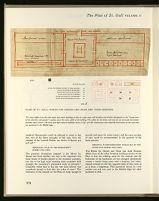

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HEN HOUSE. Authors' reconstruction

473.B SECTION

473.A PLAN

473.C ELEVATION

For SITE PLAN showing relationship of the HENHOUSE to GOOSEHOUSE

and to FOWLKEEPERS' HOUSE, see figure 466. X, page 265, and figure 466.

The installation of the monastery's poultry in circular enclosures indicates that this kind of structure was not only in use at the time the Plan

was made, but was sufficiently well known to be proposed as an exemplary solution for a monastic community of some 250-270 people. The

enclosure provided for maximum flock size with greatest economy of space. With eggs a chief source of protein in the monks' diet, the more

haphazard methods of raising poultry—i.e., letting birds run and nest at will all over the farmyard—were inappropriate; there was no time in

so well-regulated a community to search each morning for the eggs of perhaps several hundreds of birds! Feeding, watering, sanitation, and

doctoring were likewise attended to with ease through the architectural sophistication of circular fowl houses. A disadvantage of this type of

enclosure is that it cannot readily be enlarged, and is thus most appropriate for a community of planned population.

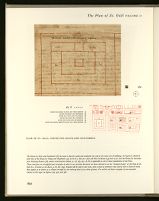

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

474.

474.X

This house differs from the other guest and service buildings in that its center space with fireplace and benches (designated as the "living room

of the oxherders and grooms") reaches across the entire width of the building. The stables for the horses and oxen do not surround, but extend

laterally away from it. The early and high medieval buildings shown in figs. 477-481 demonstrate that tripartite long houses of this type were

not uncommon in the Middle Ages.

fact; two of the finest examples of this type, from the

margins of the Luttrell Psalter, are shown in figures 475

and 476.[613]

The earliest written evidence for the use of horseshoes dates from

the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI (886-911), and in the last

decade of the ninth century "the sound of the shod hooves of horses"

is mentioned in Ekkehart's Waltharius; cf. White, 1962, 57-59, where

the whole question of the horseshoe is reviewed.

The words stabulum equarum are written by the main scribe. The

word infra which completes this title and the line supra tabulatum which

follows are annotations added in the pale ink used by the second scribe

(cf. I, 13). By contrast, all of the titles inscribed into the southern wing of

the building where the oxen and their attendants are housed are written

with the ductus and dark brown ink of the main scribe.

IMPORTANT ROLE OF THE MONASTERY'S

HORSES AND OXEN

The generous dimensions assigned to the House for

Horses and Oxen testifies, not only to the important role

these beasts of burden played in the monastic economy,

but also to the high social standing their caretakers held

amongst the monastery's permanent body of servants.[614]

Columella writes that in his day one farm laborer was

considered enough to look after two yokes of oxen.[615]

The

bedrooms of the oxherds on the Plan are large enough to

provide bed space for seven hands; and the same number

of men could be accommodated in the quarters of the

horse grooms.

The high social status of the caretakers of the plow and cart pulling

oxen among the permanent servants of a medieval estate is reflected in

the payments for their services recorded in manorial accounts. I am

quoting from R. H. Hilton's summary of these conditions in the West

Midlands of thirteenth-century England: "The most important of the

full-time servants were those ploughmen (tenatores) who actually guided

the plough, better paid than the fugatores who drove the plough animals.

Carters were normally equivalent in status to the chief ploughman,

then came the cowman, swineherd and dairymaid. Full-time shepherds

were of high status, but quite often shepherds would only be taken for

periods of less than a year, such as for the winter or summer visit of the

flock to a manor." (Hilton, 1966, 137).

MEDIEVAL & PROTOHISTORIC PARALLELS OF THE

HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN

The House for Horses and Oxen and their Keepers

differs from all the other livestock buildings shown on the

Plan in that the stabling areas for the animals and the

bedrooms of the herdsmen are not arranged peripherally

around a central living room with a fireplace, but rather,

extend outward on the two opposite sides of that room so

as to form a longhouse. This particular layout is a very

ancient one and was used in the Middle Ages for other

purposes as well.

475. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). HARROWING

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 171 (detail)

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

The harrow is pulled by one horse and led by a man. A slinger following the harrow tries to drive off two crows flying overhead. Harrows with

iron teeth or tines pegged through a wooden frame (and perhaps originally operated with wooden pegs) are among the oldest animal-powered

agricultural tools. They were used to break up clods after the soil was plowed, to level the earth for seeding, and to cover the seed after it was

broadcast. One horse, properly harnessed, as this drawing shows, was able to draw the harrow.

Royal guesthouses of the Consuetudines Farfenses

An interesting guesthouse for royal travelers, bearing

striking resemblance to the House for Horses and Oxen,

is described in the Consuetudines Farfenses[616]

, a literary

master plan for a monastic settlement written around 1043

in the monastery of Farfa in the Sabine mountains, but

now generally believed to record the layout of the monastery

which Abbot Odilo (994-1048) built at Cluny:[617]

Next to the narthex must be built a lodging 135 feet long, 30 feet

wide, for receiving all visiting men who arrive at the monastery

with horsemen. From one part of the dwelling 40 beds have been

prepared, and just as many pillows made of cloth, where only men

sleep, with 40 latrines. In the other part are arranged 30 beds

where countesses or other noblewomen may sleep, with 30 latrines,

476. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). PLOWING

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 170 (detail)

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

The plow is drawn by two span of yoked oxen guided by one man; another alongside them wields a long whip. The plow itself, with heavy

blade cutting vertically, plowshare at right angles cutting horizontally, and mould board turning the cut slice over to the side, is one of those

great innovations made by the barbarians of the North in the early Middle Ages, and one that changed the course of history. For its primitive

Roman prototype incapable of coping with the heavy alluvial soil of the North, see fig. 262, I, 348. For a superb review of the full economic

and cultural impact of this piece of equipment, see Lynn White, 1963, 44ff.

middle of this lodging should be placed tables like the refectory

tables where both men and women may eat.[618]

The Farfa Consuetudinary describes a guesthouse that is

to be an integral part of the architectural layout of an

eleventh-century monastery. (The mounts and grooms of

the traveling party were to be housed in a separate building.)

The measurements of this building, as listed in this

account, are wholly compatible with the function it was to

perform, as is demonstrated in the reconstruction of its

layout shown in fig. 477, where it is assumed that the

mattresses were ranged side by side at right angles to the

long walls. Laid out in this manner, the two wings of the

building could indeed yield sleeping space for forty men

and thirty ladies, leaving in the center a dining hall 30

feet square. The privies, as the text implies, were separate.

They could not have been arranged in a single line, as that

would have required an outhouse 175 feet long (40 feet

more than the house itself). The proportions are more

reasonable, if we assume that they were arranged in a

double row.[619]

Consuetudines Farfenses, fol. 79r-80r, ed. Albers, Cons. mon. I,

1900, 137-39, and Conant, 1968, 43.

"Juxta galileam constructum debet esse palatium longitudinis Cta

XXXta et Ve pedes, latitudinis XXXta, ad recipiendum omnes supervenientes

homines, qui cum equitibus adventaverint monasterio. Ex una

parte ipsius domus sunt preparata XLta lecta et totidem pulvilli ex pallio,

ubi requiescant viri, tantum, cum latrinis XLta. Ex alia namque parte

ordinati sunt lectuli XXXta ubi comitisse vel aliae honestae mulieres

pausent cum latrinis XXXta ubi solae ipsae suas indigerias procurent. In

medio autem ipsius palatiis affixae sint mense sicuti refectorii tabulae, ubi

aedant tam viri quam mulieres." Consuetudines Farfenses, ed. cit., 138.

Schlosser's reconstruction of this building (Schlosser, 1889, fig. 2)

lacks accuracy of detail. The reconstruction shown in fig. 477 is basically

identical with that which Kenneth John Conant suggested in 1965, 180,

fig. 1, except that instead of attaching the two privies to the end of the

building, I have placed them parallel to its northern long side, as in the

House for Distinguished Guests on the Plan of St. Gall. I am offering

this as an alternative to, not as a substitute for, Prof. Conant's suggestion.

Monks' dormitory in the monastery of

St. Wandrille

There is other, and even earlier, evidence for the use of

a longhouse of this description as sleeping quarters. The

Gesta abbatum Fontanellensium describes a building of this

type erected by Abbot Ansegis (823-833) as a dormitory

for the monks of the monastery of St.-Wandrille (Fontanella):

Moreover these are the buildings, public and private, begun and

completed by him. First of all, he had built the most noble dormitory

for the brothers, 208 feet long and 27 feet wide, the entire

work rising to a height of 64 feet. The walls were built in well-dressed

stone with joints of mortar made of lime and sand; and it

had in its center a solarium, embellished by the very best pavement

and a ceiling overhead that was decorated with the most noble

477. GUEST HOUSE OF CLUNY II (BUILT BY ABBOT ODILO, 994-1048). DIAGRAMMATIC PLAN

The similarity in layout of this house and that for the horses and oxen and their keepers on the Plan of St. Gall (fig. 474) is perplexing. Both

must derive from the same genus of buildings the protohistoric origins of which are attested by the long house of Westlick and the Carolingian or

pre-Carolingian longhouses of Warendorf (fig. 325.B). As on the Plan of St. Gall, the guest house at Cluny was located at the north-west

corner of the monastery church; also see K. J. Conant's plan of Cluny II, fig. 515, p. 335 below.

of glass. Apart from the walls, the entire structure was built with

wood from the heart of oak, and roofed over by tiles held in place

by iron nails. Above, it has tie beams and a ridge.[620]

Again, we are dealing with a building of extremely

elongated shape, with arms reaching out in opposite directions

from a central space whose function differs distinctly

from that of the extended parts. In St.-Wandrille this

central portion served as sunroom (solarium) and therefore

must have been more open than the wings in which the

478.A FONTANELLA (ST.-WANDRILLE) SEINE-MARITIME FRANCE, FOUNDED BY ST. WANDRILLE, 645

SCHEME OF CRITERIA FOR AN INTERPRETIVE STUDY

FONTANELLA (ST.-WANDRILLE)

These studies show in the Carolingian monastery of Fontanella a dormitory that is a

monastic variant of a Germanic long house of very ancient vintage, examples of which

are discussed in this chapter. Our present interpretation, differing from those proposed by

von Schlosser, 1889, Hager, 1901, and in minutiae even from one proposed by Horn

(1973, 46, fig. 47), makes no claim for authenticity in particulars. The design of the

architectural envelope, its fenestration, and its "graceful cloister walks" is an exercise

of imagination. But we feel confident of the interpretation of the disposition of primary

building masses.

The Gesta Abbatum Fontanellensium, written around A.D. 830 and 845,

describes the church of Abbot St. Wandrille, begun in 649 (here translated pending

fuller treatment in a subsequent study):

"The above-said admirable father built in this place a basilica in the name of the

most blessed prince of the Apostles, Peter, in squared stones and having 290 feet in

length and 37 feet in width."

Almost 200 years later Ansegis began construction of the cloister. First to be built was a

new dormitory (see Latin and English text, p. 277). The Gesta describes the erection

of a new refectory and a third structure, the MAIOR DOMUS:

"Thereafter he built another house called the refectory, through the middle of

which he had constructed a masonry wall to divide it so that one part would serve as

refectory, the other as cellar. This building was of precisely the same material and

the same dimensions as the dormitory . . . then he caused to be erected a third

exceptional structure which they called `the larger building'. It turned toward the

east, with one end touching the dormitory, the other adjoining the refectory. He

ordered a supply room to be installed in it, and a warming room, as well as several

other rooms. But because of his premature death this work remained in part

unfinished.

"These three most beautiful buildings are laid out in this manner: the dormitory is

situated with one end turned toward the north, the other toward the south, with its

south end attached to the basilica of St. Peter. The refectory likewise is aligned in

these two directions, and on the south side it almost touches the apse of the basilica

of St. Peter. Then that larger building is placed just as we have said above . . . . The

church of St. Peter lies to the south and faces east . . . ."

The chronicler finished his account by telling us that Ansegis "ordered graceful porches

to be built in front of the dormitory, refectory, and larger house," and that he

added midway along the cloister walk "in front of the dormitory a house for charters"

and "in front of the refectory a building in which to preserve a quantity of books."

On the use of the cloister wing that runs along the flank of the church as a place for

daily chapter meetings, see I, 249ff.

Ansegis's construction of the claustral range

of Fontanella, begun in 823, precedes

Gozbert's reconstruction of the monastery of

St. Gall by only a few years. Like St.

Gall, Fontanella conforms with the claustral

scheme emerging from Aachen in 816-817:

its ranges enclose an open court adjacent to

one flank of the church.

The topography of Fontanella did not allow

Ansegis to place the new cloister on the

south side of the church (as did Gozbert at

St. Gall, in conformity with the Aachen

scheme; cf. below, 327ff) because the old

church of St. Wandrille already stood

against the southern slope of a valley too

steep to permit further construction. But

there was ample space for building on the

flat valley floor north of the church.

In Ansegis's time the Roman supply road

from Rouen ran east of the abbey, and the

unchanneled Seine often flooded the low

valley meadows. These limitations of topography

caused Ansegis to adopt a most unorthodox

order for his claustral buildings—

cellar and refectory to the east; close to

supply routes; dormitory to the west. A

further difference is that in the Aachen

scheme all claustral structures were double-storied

whereas at Fontanella they were not;

hence their inordinate length.

Ansegis's cloister strikingly illustrates the

Carolingian search for a new order in which

a Roman passion for symmetry and monumentality

prevails over loose, casual

assembly of parts. It is furthermore a

testimony to the triumph of Benedictine

monachism over other less ordered forms of

monastic observance, and the role the Benedictine

ideals played in lending new eminence

and vigor to the quest for cultural unity

that pervaded the whole of Carolingian life.

of a large transeptal porch with heavily fenestrated gables.

AEDIFICIA autem publîca ac priuata ab ipso coepta et consummata

haec sunt: Inprimis dormîtorium fratrum nobilissimum construî fecit,

habentem longitudinis pedum CC VIII, latitudinis uero XXVII; porro

omnis eius fabrica porrigitur in altîtudine pedum LXIIII; cuîus muri de

calce fortissimo ac uiscoso arenaque rufa et fossili lapideque tofoso ac probato

constructi sunt. Habet quoque solarium in medio suî, pauimento optimo

decoratum, cui desuper est laquear nobilissime picturis ornatum; continentur

in ipsa domo desuper fenestrae uîtreae, cunctaque eîus fabrica, excepta

macerîa, de materie quercuum durabîlium condita est, tegulaeque ipsius

unîuersae clauis ferreis desuper affixae; habet sursum trabes et deorsum.

Gesta SS. Patrum Font. Coen., Book XIII, chap 5, ed. Lohier and Laporte,

1936, 104-105; ed. Loewenfeld, 1886, 54-55; ed. Schlosser, 1889,

30-31; and idem, 1896, 289, No. 870. For an earlier visual reconstruction

of Ansegis's cloister see Horn 1973, 46, fig. 47.

Protohistoric houses of similar design

I mentioned before that this particular layout was a very

ancient one. Longhouses of comparable design were excavated

by Doppelfeld in a Migration Period settlement on

the Bärhorst, near Nauen, Germany;[621]

by Bänfer, Stieren,

and Klein in a Migration Period settlement at Westick,

near Kamen, Westphalia;[622]

and by Winkelmann, at Warendorf,

near Münster,[623]

in a settlement datable by its pottery

to A.D. 650-800 (fig. 478) This building type spread from

the Continent to England, where it is attested by a

Saxon longhall of the ninth century, excavated in 1960-62

by Philip Rahtz in Cheddar, Somerset (fig. 479)[624]

and

numerous buildings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

when it became a favorite layout for monastic barns in

the counties of Wiltshire, Gloucester, and Somerset. Figures

480 and 481 are typical examples. The first is a broadside

view of the fourteenth-century barn at Pilton, Somerset,

a dependency of the abbey of Glastonbury; and, the

second, a plan of the fifteenth-century barn of Tisbury,

Wiltshire, one of the outlying granges of the abbesses of

Shaftsbury.[625]

For Pilton, see Andrews, 1901, 30; Cook-Smith, 1960, 30-31,

and figs. 207-210; and Crossley, 1951, fig. 130. For Tisbury, see Andrews

loc. cit.; Dufty, 1947. The roof of the barn of Pilton was destroyed by

fire in 1963 (cf. Horn & Born, 1969, 162).

Reconstruction

In our reconstruction of the House for Horses and Oxen

and Their Keepers (fig. 482A-G), we have emphasized the

function of the domus bubulcorum & equas seruantium as

the living, dining, and cooking area of the herdsmen (and

perhaps an even larger segment of the monastery's serfs

and laymen) by giving to this portion of the building the

form of a large transeptal hall, whose ridge intersects the

ridge of the stables. We have interpreted the bedrooms of

the oxherds and grooms as aisles, attached to the flank of

the stables; the stables themselves, as internally undivided

spaces whose roofs are carried by a continuous set of

coupled rafters of uniform scantling. There are other

478.B AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON THE GESTA ABBATUM FONTANELLENSIUM et alii BY THE AUTHORS

we have introduced four posts, which are not shown on

the Plan; we have assumed them because it appeared

unlikely to us that in a service building of this type the

roof would have rested on beams spanning nearly 40 feet.

V.17.4

HOUSE FOR COWS AND COWHERDS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Hic arm[enta] tibi laċ fa & us lac atq· ministrant[626]

Here the cows furnish you with milk and offspring

Directly west of the House for Horses and Oxen, within

the fences of a large rectangular yard containing four other

livestock buildings, is the House for the Cows and Cowherds

(fig. 483). Its title makes it irrevocably clear that the

animals that find shelter in this structure perform the dual

role of serving as dairy and breeding stock. The house is

entered broadside by a door leading directly into the "hall

of the herdsmen" (domus armentariorum), which is provided

with the customary central fireplace. Ranged on three sides

around this space, in the shape of the letter U, are the stables

for the dairy cows (stabula); the extremities of this stable

479. CHEDDAR, SOMERSET, ENGLAND. LONG HALL OF THE SAXON PALACE. 9TH CENTURY

[after Rahtz, 1962-63, 58, fig. 20]

The house, slightly boat-shaped (most markedly so on the west side) was 78 feet long externally, and 20 feet wide across the middle. Its walls

consisted of closely spaced posts, 9 inches square, set against the outer edge of a continuous trench, and in certain places doubled by a row of

inner posts of lighter scantling sloping inward. The entrances were in the middle of the long walls, with a minor one toward the north end of the

east side. A spread of burnt clay in the southern half of the house close to the center may indicate the location of the hearth.

"bedrooms for the servants" (cubilia seruantiū).

Both Keller and Willis[627]

interpreted the area designated

as domus armentariorum as an "open court" and the square

in its center as "a small house perhaps inhabited by the

overseer." There would be no need to refer to this superannuated

interpretation had it not been rescuscitated lately

in Alan Sorrell's recently published reconstruction of the

sufficiently stressed in earlier parts of this study, can only

have referred to a covered portion of ground. It is the

author's favorite term for "hall" or "living room" and

cannot under any circumstances be interpreted as "courtyard."

The square in the center, which is common to all

the guest and service buildings on the Plan, is clearly

identified in some of them as "fireplace" and in others as

"louver."[629]

The House for the Cows and Cowherds is 87½ feet long

and 50 feet wide, but whether this is the length of the

original scheme is somewhat doubtful, since in this corner

of the Plan the parchment contracts, and it is possible that

the copyist found himself compelled to reduce the length

of the building in order to adjust to this condition.

The central hall of the cowherds measures 22½ feet by

52½ feet; its aisle and lean-to's have a width of 17½ feet.

The traditional way of housing a dairy herd was to tie the

cows in pairs in stalls 5 feet long and 7 feet wide.[630]

The

aisle and lean-to's of the House for the Cows and Cowherds

are wide enough for the animals to be tied up in two rows,

one facing the outer walls (their customary protohistoric

position) and another one facing the inner wall partitions.

If stalled in this manner, the House for the Cows could

have accommodated a total of seventy cows. If they were

tied in a single row against the outer walls only, this figure

would have to be reduced to forty.

480. PILTON, SOMERSET, ENGLAND. BARN OF GLASTONBURY GRANGE. 15TH CENTURY

[Photo: Quentin Lloyd]

Long barns with one or several transeptal porches are very common in the Midlands and southwest of England. They are rarely less than 100

feet long, often come close to 200 feet; and one example, the barn of the Benedictine abbey grange of Abbotsbury, Dorset, attained the astonishing

length of 267 feet. The building type has never been systematically studied. For individual examples see Andrews, 1900, passim; Horn and

Charles, 1966, Horn and Born, 1969, and Charles and Horn, 1973. F. W. B. Charles and Jane Charles recently measured this barn for us. It

is 108 feet 6 inches long, 44 feet wide, and 17 feet high from floor to wall head.

The inscription is damaged. Hic armenta tibi [lac] faetus lac atque

ministrant is the traditional reading. After the title was written, lac was

shifted forward from its position between faetus and atque to a place

between tibi and faetus; but the scribe failed to erase or strike out the

superfluous lac.

MILK AND CHEESE:

PRIMARY ITEMS IN THE MONKS' DIET

The primary purpose of this herd of dairy cows was to

provide milk and cheese for the table of the monks. Butter

does not seem to have been an important item in the monastic

diet. The records of the monastery of St. Gall list altogether

not more than one pint of butter.[631]

From the same

records we learn that in the territory of St. Gall cheese

came in two sizes: a large round cheese (caseus alpinus) of

the same diameter, more or less, as a Swiss cheese of

today, usually cut into four parts (qui secantur in IV partes),

occasionally into six or eight; and a "hand cheese," which

was cut into two parts only (qui secantur in duas partes).

Cheese was one of the most common articles of tithing

contributed by the outlying farms, especially those in the

mountains which specialized in cattle raising; and the

annual revenue at St. Gall from its possessions in the

territory of Appenzell alone was over 2,000 cheeses.[632]

MEDIEVAL PARALLELS

The external appearance of the House for the Cows and

Cowherds must have been very similar to that of the

Gardener's House (figs. 426-427), except that it was considerably

larger, as one would expect it to be in view of its

different function. It is the standard house of the Plan,

minus one aisle on one of its long sides, which makes the

main room of the house directly accessible from the exterior,

a distinct advantage in buildings where great numbers

of the larger breeds of animals, and especially horned

cattle, are sheltered, because this arrangement reduces the

number of doors through which the cattle must be taken as

they enter and leave their stalls (figs. 483, 486). This house

type must have been very common in the Middle Ages. The

earliest literary evidence for its existence, so far as I can

judge, occurs in a dossier of twelfth-century lease agreements

that record the manorial holdings of the Dean and

Chapter of St. Paul's in London.[633]

On a manor located in

481. TISBURY, WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND. PLAN, GRANGE BARN. 15TH CENTURY

[Redrawn after Dufty, 1947, 168, fig. 2]

The barn at Place Farm was part of a grange once owned by the abbesses of Shaftsbury. Its external dimensions are 196 feet long by 38 feet

wide. It is lengthwise divided into 13 bays by roof trusses with arch-braced collar beams meticulously aligned with the buttresses of the masonry

walls. Two transeptal porches in the middle of the barn are original. The masonry of the jambs of the other four entrances is modern; these

openings were probably not part of the original structure. The roof is thatched.

these lease agreements is described as follows:

Juxta hoc orreum est aliud, quod habet in longitudine xxx. ped. et dim.

preter culacia: et unum calacium est longitudine x. ped. et. dim.

Alterum viii. ped. Tota longitudo hujus orrei cum culatiis xlviii. ped.

Altitudo sub trabe xi. ped. et dim. et desuper usque ad festum ix. ped.,

latitudo xx. ped.; nec habet preter i. alam, quae habet in latitudine v.

ped. et in altitudine totidem. Hoc orreum debet Ailwinus reddere plenum

de mancorno preter medietatem quae est contra ostium, quae debet

esse vacua, et haec pars est latitudinis xi. ped. et dim.[634]

Adjacent to this barn there is another one, the length of which is

30½ feet, not counting the lean-to's. One of the lean-to's is 10½ feet

deep, the other 8 feet. The total length of the barn, lean-to's included,

is 48 feet. The height below the tie beam is 11½ feet, and

above, between the tie beam and the ridge, 9 feet. The width [of

the nave] is 20 feet. And it has only one aisle, which is 5 feet wide

and equally high. This barn Ailwinus must render full of mancorno

with the exception of the center bay which lies opposite the entrance

and must be left empty, and this part is 11½ feet deep.

The barn of Wickham is just a little over half as large as

the House for the Cows and Cowherds on the Plan of

St. Gall, but its layout is identical. It is noteworthy that

the twelfth-century writer in describing this barn makes a

clear distinction between the aisle (ala) which is attached

to one of the two long sides of the barn and the two leanto's

(culatium) which are attached to the narrow ends of the

building. In English this distinction is not always maintained.

Culatium (from culus = pars cujusvis rei posterior[635]

)

is a highly descriptive term for that section of the barn which

lies under the hipped part of the roof at the short end of

the building. The writer also makes a clear distinction

between the principal space of the barn, which he refers to

simply as "barn" (orreum), and all the peripheral spaces.

The dimensions listed for all the constituent parts of the

building make it clear that the center space was higher

than the surrounding spaces and that it had a double-pitched

roof (fig. 485A-D). This is strong evidence for

the correctness of our reconstruction of the House for the

Cows and Cowherds (fig. 486A-E) and all the other buildings

on the Plan which are laid out in a similar manner.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES, OXEN, AND THEIR KEEPERS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION [1:192]

482.B

482.A LONGITUDINAL SECTION

PLAN

The only difference between the medieval long houses with transeptal porches shown in figs. 477-481 and the House for Horses and Oxen (fig.

474) is that the latter is furnished with aisles serving as quarters for the oxherds and horse grooms. Traditionally this building type is single-spaced

and in this form either used as a dwelling, or for the storage of harvest. Aisles were incorporated in the House for Horses and Oxen

because it was intended to accommodate both men and beasts.

The total length of this building on the Plan is 145 feet; the living space measures 35 by 37½ feet and the stables each are 52½ feet long,

suggesting that the roof-supporting trusses were placed at 11½ foot intervals.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

482.D WEST ELEVATION

482.C EAST ELEVATION

SCALE 1/16 INCH EQUALS ONE FOOT [1:192] FOR GRAPHIC SCALE SEE PRECEDING PAGE

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Our reconstruction of this house as a transeptal space the ridge of which intersects the main ridge at right angles and at the same height, is

made in consideration of the fact that the transept extends across the entire width of the structure, bisecting the aisles in which the herdsmen

were to sleep. We are also visually emphasizing the great importance of this transept which may have been intended to serve as dining area for

all of the monastery's herdsmen (cf. above, p. 278).

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

NORTH ELEVATION is similar but of opposite hand to

the SOUTH ELEVATION

482.F TRANSVERSE SECTION B-B

482.E SOUTH ELEVATION

482.G TRANSVERSE SECTION C-C

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

We saw no functional need to raise the roof over the aisles, where the oxherds and horse grooms were to be quartered, above tie-beam level of the

stables. In this same manner bedrooms are treated in all the other guest and service buildings of the Plan. To extend the main roof across the

entire width of the building would have been considerably more costly and in construction functionally superfluous—unless one can assume that

the full width of the building at floor level was needed as loft above the tie-beam level for storage of straw and hay.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR COWS AND COWHERDS

483.X SITE PLAN

Virtually all of the houses for monastic livestock lie in a large rectangular yard that extends from the entrance Road to the southern edge of the

monastery site. They consist of the House for Sheep and Shepherds (No. 35); the House for the Goats and Goatherds (No. 36); the House for

the Cows and Cowherds (No. 37); the House for the Swine and Swineherds (No. 39); and the House for Broodmares and Foals and their

Keepers (No. 40). The House for Horses and Oxen and their Keepers (No. 33 and fig. 474) lies outside this yard, but adjacent.

The layout of the House for Cows and Cowherds is identical with that of the House for Broodmares and Foals and their Keepers as well as

with that of the Gardener's House (fig. 426). In each of these structures, the common living room with its traditional open fire place is

surrounded with subsidiary outer spaces on three sides only (variant 3B; see above, p. 85, fig. 33). The entrance is in the middle of the long

wall where the aisle is missing. As in the House for Distinguished Guests (figs. 396-399), in order to gain access to the stables animals have to

be taken through the common living room. For a 12th century structure of the same design see p. 281 and figs. 485. A-D.

484. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). DEUTERONOMY, XXXII: 1-4

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 86r (detail)

[Courtesy of Utrecht University Library]

The illusionistic Late Antique style was practiced with superb assurance by the illuminator of the lost manuscript after which the Utrecht

Psalter was modeled. Scenes of agricultural life such as this one of a herd of cattle and a man churning butter are of a richness of perception

surpassing any other Carolingian manuscript. This intensely classical style disappeared from the medieval scene almost as rapidly as it was

adopted, giving way to more abstract concepts of painting. It took close to 500 years of gradual reconquest of reality by art for rural scenes

again to be as accurately depicted as in this unique Carolingian manuscript. The marginal scenes of the Luttrell Psalter (figs 467, 475, and

476) are among the high-water marks in this development that, at certain stages, was stimulated by availability of copies of the Utrecht

Psalter that were made in England in the 10th and 11th centuries.

The lease agreements of St. Paul's date from 1114 to

1155.[636]

Obviously, they establish only a terminus ante quam,

telling nothing about the age of the barns. Some of them

may have been of relatively recent date, others may have

been centuries old.

For the dates of the leases, see Hale's introductory notes, op. cit.,

xc-c. Cf. Horn, 1958, 11-12.

V.17.5

HOUSE FOR BROOD MARES, FOALS

AND THEIR KEEPERS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Hic fa&as seruabis equas tenerosq· caballos

Here you will attend to the brood mares and to

their foals

The House of Foaling Mares (fig. 487) is identical in plan

to that for Cows and Cowherds. In all likelihood it was

meant to be the same size. The narrowing of the parchment

at the southwestern corner of the Plan, where this building

is located, probably forced the copyist to contract the plan

for this house. The room that contains the hearth is designated

"the horsemen's living room" (domus equaritiae:

"the hall of the stables where horses are bred"[637]

); aisles

and lean-to's that accommodate the horses are designated

"stables" (stabula); the cubicles at their end, as "bedrooms

for the attendants" (cubit custodum).

For other sources for equaritia, see Niermeyer, 378. In all the houses

of the Plan of St. Gall in which animals are kept, they are stabled in the

aisles and lean-to's, never in the center room, which is the living room of

their keepers.

MATING AND BREEDING

Columella, in his book On Agriculture, states that stallions

and mares of common stock may be mated at any time

during the year, but he advises that the nobler breeds be

mated about the time of the spring equinox so that the

mares, who foal in the twelfth month, may be able to

WICKHAM ST. PAUL'S, ESSEX. BARN 2 OF THE DEAN AND CHAPTER OF ST. PAUL'S, LONDON

485.D.3

485.D.2

485.D.1

485.B

485.C

485.A

Descriptions in 11th-century leases of agricultural buildings maintained by the

Dean and Chapter of St. Paul's on outlying estates (The Domesday of St. Paul's

of the year MCCXII . . . W. H. Hale, ed., London, 1858, 122-39) are so accurate

that the structures can be laid out on the drafting board. Since no 11th- and 12thcentury

barns survive, this material forms a unique link between proto- and early

medieval Wohnstallhäuser (above, pp. 45ff) and the earliest surviving medieval

barns (above, pp. 88ff). The example here shown belongs to what we earlier defined

as Variant 3B of the St. Gall house (fig. 333). For reconstruction of two others

(Variant 4), see Horn, 1958, 12, figs. 24 and 25.

PLAN, SECTIONS, AND AXONOMETRIC DRAWINGS SHOWING SKELETAL FRAMING AND EXTERNAL ENVELOPE

points out that pregnant mares need special care and

generous fodder and ought to be kept in a place that is

both roomy and warm.[638] Modern breeding manuals prescribe

that maternity stalls be 12 feet by 12 feet.[639] If these

were the dimensions of the stalls used in the House for

Foaling Mares and Foals, it would have been able to

provide shelter for eleven mares and their offspring at any

given time. The hay, straw, and grain required for these

animals were usually stored overhead under the slope of the

aisle roof and were fed into the mangers through openings

in the floors of these lofts.

V.17.6

HOUSE FOR GOATS AND GOATHERDS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Ista domus cunctas nutrit seruat q· capellas

This house feeds and shelters all the goats

The House for Goats and Goatherds (fig. 489) lies near the

House for Cows and Cowherds. Its layout is that of

the standard house of the Plan. In the hexameter explaining

its function, the word domus appears in the sole context

of the Plan where it means the entire building. The

living room bears no inscription. It is reached through a

vestibule that divides the eastern aisle into two separate

chambers used as "bedrooms of the herdsmen" (cubilia

pastorum). The lean-to's and the western aisle of the house

are designated as "stable" (stabula). The building is 57½

feet long and 45 feet wide. The living room measures 37½

feet by 25 feet.

Columella recommends that not more than 100 head of

goats be kept in one enclosure. He advises the goatherd to

sweep out the stable every day and not allow any ordure or

moisture to remain or any mud to form. The she-goats

should be covered in the autumn, sometime before December,

so that the kids may be born when spring is

approaching and the shrubs are budding.[640]

He devotes a

whole chapter to the making of goat cheese.[641]

MANAGEMENT OF SIZE OF HERD

The House for the Goats and Goatherds could easily

have sheltered one hundred goats. It was probably used

primarily for the purpose of milking and breeding the

goats. Shortly after the young were born in the spring, and

had gathered sufficient strength, they were no doubt taken

out to pasture by the goatherds, a breed of men who,

Columella stipulates, should be "keen, hardy, and bold . . .

the sort of men who can make their way without difficulty

over rocks and deserts and through briers . . . men who do

not follow the herd like the keepers of other breeds of

cattle, but precede it."[642]

The rooms in the eastern aisle of

the House for the Goats and Goatherds on the Plan are

large enough to accommodate, besides the permanent goatherds,

a considerable number of extra hands who during

the warmer months of the year took care of the herds that

were out to pasture.

MILK PRODUCTION

Modern farming manuals state that two reasonably well-bred

goats will supply an average household with all the

milk it requires and most of the butter, each goat being

able to produce 250 gallons of milk or 100 pounds of

butter per year.[643]

If the House for the Goats and Goatherds

sheltered one hundred goats at a time, these animals must

have contributed considerably to the monastery's daily

supply of cheese.

In layout, design, and dimensions, the House for the

Goats and Goatherds is identical with the House for

Visiting Servants (figs. 402-403), which relieves us of its

reconstruction. The same holds true for the two remaining

buildings of this tract, which we shall discuss presently.

V.17.7

HOUSE FOR SWINE AND SWINEHERDS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Iste sues locus enutrit custodit ad/& ultas[644]

This place nourishes the [young] pigs [and]

guards the mature sows

The House for Swine and Swineherds (fig. 491) lies west of

the House for the Goats and north of the House for Foaling

Mares. Its center room, which has a fireplace, is designated

"the hall of the swineherds" (domus porcariorum). The east

aisle contains a vestibule and the "bedrooms of the herdsmen"

(cubil pastorum). The west aisle and the lean-to's are

not designated. There can be no doubt, however, about their

function. In all the other houses, this area was reserved for

the animals.

A FARROWING PEN

The House for Swine and Swineherds, as its explanatory

title states, was primarily a farrowing pen. It was the place

where the sows were kept during the winter—those sows,

that is, who would produce the litters to make up the

subsequent year's herds. All other pigs were slaughtered

in December.[645]

The number of pigs that could be housed

together is determined by available trough space. Feed

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR THE COWS AND COWHERDS

486.B EAST ELEVATION

486.A PLAN

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

In reconstructing this building we were in principle guided by the same criteria that governed reconstruction of the House of the Gardener and

his Crew (figs. 427. A-F), but because this house is the larger by over twice the area of the former structure, we decided to furnish it with a

hipped roof on the supposition that it would be needed for greater wind resistance.

As for all structures housing both men and animals on the Plan, it was necessary to lead animals to their stalls directly through the common

living area used by the herders, whose sleeping quarters in the aisles may have been divided from the stalls by little more than a partition.

486.D TRANSVERSE SECTION B-B

486.C LONGITUDINAL SECTION A-A

486.E NORTH ELEVATION

The habit and custom of housing beasts in close contact with man was of centuries' long standing in Northern Europe. Even in the sophisticated

House for Distinguished Guests (Building 11; cf. fig. 396, p. 146), 9th-century social amenities did not yet preclude the arrangement whereby

the visitors' horses were led through the common living and dining area to their stalls.

The length of the center space of the House for Cows and Cowherds is 52½, feet, suggesting that its roof supporting posts were to be spaced at

10½-foot intervals, or within the normal range for bay division in a building of this kind.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR FOALING MARES AND THEIR KEEPERS

487.

487.X

Lying in the extreme southwest corner of the site, the layout of this structure in all of its basic dispositions is identical with that of the House

for Cows and Cowherds. Virtually without question it was intended to be the same size, but, falling at a point on the tracing where the

parchment corner tapers, the draftsman of the Plan was doubtless compelled to reduce the size of the building slightly in accommodation to the

limitations of his sheet.

All the larger breeds of livestock were quartered in separate facilities lying in close proximity to one another. Outlines on the Plan indicate

that they were separated by fences or other partitions from one another. During the winter, animals would be confined to their stalls; in spring

they could be taken to pasture through secondary exits in the peripheral wall enclosure (which are not shown on the Plan).

Horses and oxen kept in these facilities would be used as draft animals, the former perhaps for riding; the cattle for breeding and milking; the

mares exclusively for breeding. As regards the inclusion of a stud in a monastic community, the relationship of monastic with crown services and

economics is discussed in Volume I, Chapter IV, "The Monastic Polity."

488. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). PSALM LXXII (73)

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 41v (detail)

[Courtesy of the Utrecht University Library]

This detail is one of the most interesting examples of the method used by the illuminator of the original Late Antique manuscript (after which

the Utrecht Psalter was modeled) to convey general concepts in imagery taken from man's daily life. Verse 22 of the psalm, "So foolish was I

and ignorant; I was as a beast before thee", serves to embody the concept "beast" in the touching representation of a mare suckling her foal. In

this manner the illuminator transmitted to the Middle Ages a composition borrowed from one of the best periods of Roman painting. It has a

striking counterpart in a painting from Herculaneum (now in Naples, Museo Nazionale) showing a doe suckling Telephos (see L. Curtius, Die

Wandmalerei Pompejis, Leipzig, 1929 8, fig. 5).

and boars, 18 inches. The required sleeping and feeding

area is 6 square feet per pig. The minimum farrowing pen

is 5 feet square. There should also be a dung passage 3 to 4

feet wide.[646] If the area available for pigs in the House for

Swine and Swineherds on the Plan were to be divided into

farrowing pens 5 feet square, it would accommodate twenty-one

sows with litters (five under each lean-to; eleven in the

aisle). If the housing capacity were to be calculated on the

basis of the available square footage, without allowing

extra space for litters, the number of pigs could easily be

doubled.

MEAT FOR THE SERFS, AND FOR THE YOUNG

AND SICK MONKS

In the Middle Ages swine and sheep were the chief

animals raised for meat. Many monasteries maintained

large herds of both, often under the supervision of the

monks themselves. Swine and sheep were also favorite

items of tithing. In the deeds of the monastery of St. Gall,

published by Hermann Wartmann, sucklings, yearlings,

and fully fattened sows are often part of the regular deliveries

from villagers and other tenants. In calculating these

tithes, a distinction was made between the heavy winter

swine, which had been fattened on acorns and beechnuts

while out to pasture in the forest, and the leaner and

less desirable summer swine. In years when the weather

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR GOATS AND GOATHERDS

489.

489.X SITE PLAN

The House for Goat and Goatherds (36) lies next to that for cattle and cowherds (37) and in the same row of buildings. Its layout is identical

with that of the House for Sheep and Shepherds (35) north of it, that for swine and their herdsmen (39) west of it, and the House for Servants

from Outlying Estates (38), whose reconstruction (below, p. 157, fig. 403. A-D) is applicable to all of these installations of the Plan.

These structures are straightforward examples of what in our previous discussion we have referred to as the "standard house" of the Plan of St.

Gall (i.e., Variant 4; see above, p. 85, fig. 334). Ranged side by side in two rows, with a sense of symmetry that clearly had a classical touch,

they appear to us almost as a village arranged by the ordering mind of an urban planner. For earlier and later examples of non-monastic

clusters of this type, see figures 259, 335, and 336.

490. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). PSALM XXII (23)

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 45r (detail)

[Courtesy of Utrecht University Library]

The five goats grazing on a hillside are part of a larger scene; it includes a herd of cattle and flock of sheep by the banks of a stream, to

illustrate verses 1 and 2 of the psalm: "The Lord is my shepherd . . . . "

The pen-and-ink depiction of these goats, two of which rise on their hind legs reaching as high as they can to crop the choice leaves, and

snapping at each other in their greed, is a display of posture and behavior so distinctively of goats that it places this scene among the outstanding