The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. | V. 14 |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 14

FACILITIES FOR STORAGE AND

THRESHING OF GRAIN

V.14.1

THE MAIN GRANARY

Between the Great Collective Workshop and the Gardener's

House is a large Granary (fig. 431) for storing the annual

harvest and threshing the grain:

Frugibus hic instat cunctis labor excutiendis

Here is pursued the labor of threshing the entire

harvest

The draftsman takes great care to define the two complementary

functions of this building: the first, with an

inscription, "barn, i.e., storehouse for the annual harvest

of grain" (horreum um repositio fructuü annaliū);[462]

the second,

by designating a cross-shaped area of ground as "the area

where grain and chaff are threshed" (area in qua triturant'

grana et paleae).

The Granary is 47½ feet wide and 90 feet long. Its axis

runs from south to north. The building has only one

entrance, in the middle of its western long wall; it is a

double-winged door wide enough to allow the loaded

wagons to enter. It is not likely that a barn of these dimensions

would have been covered by a single span in the

ninth century. Even in the great monastic barns of the

thirteenth century the roof was carried by two rows of

freestanding inner posts when the width of the barn exceeded

25 feet. The draftsman must have taken these constructional

features for granted. Had the Granary been intended

to shelter human beings or animals as well, the floor plan

would have indicated the wall partitions separating the

spaces used for storing the harvest from the spaces reserved

for people or animals; and the course of these partitions

would, in turn, have given us a clue to the location of the

roof-supporting posts. But the barn of the Plan of St. Gall

had no such secondary function, except that a certain

amount of its floor space had to be kept vacant for threshing.

The draftsman makes this clear by carefully delineating

the surface area needed for this purpose: two threshing

lanes intersecting each other at right angles, each lane about

12 feet wide, i.e., the distance two rows of men would

require when flailing grain from opposite sides.

The layout of the Granary of the Plan of St. Gall teaches

us that broadside access must have been a very common

feature, if not the standard form, in Carolingian barn

construction. It was and remained throughout the entire

432. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 173

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

Three men stack bound sheaves of grain while two others carry sheaves to the pile. The work of cutting and sheaving grain is arduous; it must

be cut when the kernels are still in the barb and sufficiently moist so that the grain heads will not shatter and spill the harvest to the ground.

At this point the grain stalks are technically "green", and too tough to scythe, but must be hand cut with sickles.

English barn construction. In medieval France and in the

medieval and post-medieval dwelling barns of Lower Saxony

the entrances were invariably in the gable walls. In the

Lowlands and in southern Germany—as a glance at the

engravings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder or the watercolors

of Albrecht Dürer (figs. 335; 336) show—the two types are

mixed.

A typical English parallel comparable in size to the

Granary of the Plan of St. Gall is the priory barn of Little

Wymondley, Hertfordshire (fig. 434A-C)[463]

, probably dating

from the first half of the thirteenth century. Other examples

of the same period, both English and Continental, were

discussed above on pp. 103ff. The earliest evidence, other

than the Plan of St. Gall, for monastic barns with broadside

entrances are the barns that the Dean and Chapter of the

cathedral of St. Paul's in London maintained on its outlying

estates in the counties of Hertfordshire, Essex, Middlesex,

and Surrey. They are described in lease agreements

dating from 1114 to 1155.[464]

A careful reading of these texts

makes it clear that traditionally the harvest was stored in

this type of barn by filling the bays closest to the gable walls

first and working from there toward the center of the

building, the center bay being left empty for the entry and

exit of the wagons. This center bay was thus the natural

place for threshing. In many of the surviving English

medieval barns these entrance bays are paved, either in

stone or with wooden planks, and were used for threshing

until the invention of modern harvesting machinery[465]

eliminated the need for any such provisions (cf. fig. 437).

433. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 173v

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

In moderate climates, sheaved grain may be stored in the field for a few days to many weeks. Sheaves are stacked upright and over them, a few

sheaves are splayed with grainheads down, to form a protective thatching that sheds occasional rain. In northern climates the sheaves had to be

under shelter long before the onset of autumn rains; hence the great size of the Plan's threshing barn. The cart of the Psalter, with three

horses and three men, does not exaggerate the weight of the sheaves nor the labor required to load them.

Our reconstruction of the Granary of the Plan (fig. 435AE)

is not modeled after any particular example. We have

chosen a type that might have been found anywhere at any

time during the Middle Ages. We have given it a roof with

rafters of uniform scantling and hipped bays at the end,

because of the restraining effect such lean-to's exert on

any tendency of such a roof to give way under longitudinal

stresses. We could also have reconstructed it as a purlin

roof, analogous to Little Wymondley, except for the curved

arch and wind braces of this building which are typically

English and have no parallels on the Continent.

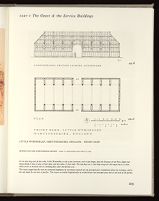

434.C LITTLE WYMONDLEY, HERTFORDSHIRE, ENGLAND. PRIORY BARN

FIRST HALF OF THE 15TH CENTURY

EXTERIOR VIEW FROM THE SOUTHWEST

A classical example of a medieval monastic barn of England, its purlin roof is hipped over the terminal bays; two transeptal porches give

access to the center bay. The barn does not, as we formerly believed, date to the 13th century when the priory was founded, but was rebuilt in

the 15th century on the site of an earlier building; some beams from previous structure were reused to make this one. Had the Granary of the

Plan been built, it would have resembled this one in many details.

LITTLE WYMONDLEY, HERTFORDSHIRE, ENGLAND. PRIORY BARN

434.B

434.A

GROUND PLAN AND LONGITUDINAL SECTION SCALE INCH EQUALS ONE FOOT [1:192]

At 100 feet long and 38 feet wide, Little Wymondley is only 9 feet narrower, and 10 feet longer, than the Granary of the Plan. Eight roof

trusses divide it into a nave, 23 feet wide, and two aisles, 7½ feet wide. The nine bays are 11 feet deep except for the wagon bay at 12 feet,

which serves as entrance and as threshing floor after the harvest is in.

The trusses supporting the roof are connected lengthwise by roof plates tenoned into the principal posts immediately below the tie beams; and in

the roof slopes by two tiers of purlins. The trusses are locked longitudinally by arched braces into principal posts and at the level of the purlins.

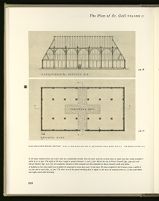

PLAN AND LONGITUDINAL SECTION SCALE INCH EQUALS ONE FOOT [1:192] GRAPHIC SCALE, 408.D, PAGE 172 FOR COLOR PLAN SEE P. 214

435.B

435.A

In all major medieval barns the center aisle was considerably broader than the outer aisles by at least twice as much; but they rarely exceeded a

width of 21-23 feet. The depth of the bays ranged in general between 11 and 13 feet. Barns the size of Great Coxwell (figs. 349-351) and

Parçay-Meslay (figs. 352-355) are exceptions; because of their unusual size they depended on heavy masonry walls and gables.

A building 90 feet long would most probably be comprised of seven bays each 13 feet deep. We have assigned to the Granary nave a width of

22½ feet and to each aisle, 12½ feet. The short arm of the paved threshing floor is edged, in the nave, by unpaved areas ca. 5½ feet wide where

men might stand while threshing.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. GRANARY. AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

435.C

435.D

435.E

TRANSVERSE SECTION, SOUTH ELEVATION AND WEST ELEVATION

Enough is known about the history and protohistory of the medieval barn to allow a safe assumption that a building 47½ feet wide and 90 feet

long would have been an aisled structure. But there is no reason to assume that any part would have been of masonry except for the foundations

and a shallow plinth on which to foot the upright timbers and protect them from dampness. In the majority of medieval and prehistoric

buildings of this type the roof was hipped over the terminal bays (compare prehistoric examples, figs. 295-97, 313-14, and medieval barns and

houses portrayed by Dürer, fig. 335, and by Bruegel, fig. 336).

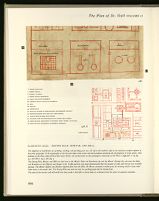

436. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BREWERS' GRANARY

The location of the Brewers' Granary (30) next to the Monks'

Bake and Brewhouse (9), the Mortar (28) and Drying Kiln (29),

and its proximity to the Bake and Brewhouse of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers (32) is ideal, since the work performed in all

of these installations represents separate and successive stages in the

making of beer: threshing, crushing, parching and brewing. If the

threshing floor of the Brewers' Granary seems disproportionately

large, it may owe to the fact that much less grain needed to be

stored there for any length of time, although the work of threshing

for brewing no doubt was continuous (cf. fig. 431. X).

The Granary of the Plan of St. Gall was the storage

place, I should imagine, not only for the harvest yielded

by the fields that the monastery worked with the aid of its

own serfs, but also for the revenues obtained through the

tithing of land leased out to tenants.[466]

The volume of the

annual revenues derived from any of these sources was a

carefully regulated matter. Abbot Adalhard of Corbie, who

had to take care of a monastic community of an average of

300 souls, furnished a detailed account of the manner in

which the supply of grain was handled in his own monastery.

The total income in grain "well winnowed and husked"

(spelta bene uentilata et mundata) was 750 baskets per year

(two baskets per day plus 20 additional baskets for safety).[467]

Abbot Adalhard informs us that two baskets average ten

modii, each modius yielding 30 loaves of bread; two baskets

thus giving assurance of 300 loaves per day. He establishes

how many sheaves make up a modius of grain, allowing for

the variation in quality of grain obtained from different

fields, and he draws attention to the detrimental effect of

such variance on the attempt to attain an accurate system

of measurement. He points out that the straw ought always

to be delivered with the grain, as it, too, has uses, and he

rules that when places are too far away for the tithe to be

carted in, the villages lying near should pay double tithes

and then collect from their neighbors farther out. In conclusion,

he admonished the Porter, who is in charge of all

these operations, to keep an accurate inventory of all these

deliveries.[468]

The symbol ·|· must be interpreted as id est; see Battelli, 1949,

114, and Cappelli, 1954, xxxiii, and 168. The symbol was mistakenly

read as vel by Willis, 1848, 112; Stephani, II, 1903, 52; Leclercq, in

Cabrol-Leclercq, 1924, col. 104; and Reinhardt, 1952, 14. Keller, 1844,

3, failed to list this line.

The barn of Little Wymondley belonged to Wymondley Priory,

which was founded during the reign of Henry II by Richard de Argentein,

lord of the manor of Great Wymondley, sometime before 1218.

See Victoria History of the Counties of England, Hertfordshire, III, 1912,

190. It lies immediately to the south of the Priory House and, in all

probability, is the original Priory Barn. Cf. Horn, 1963, 18ff. (Radiocarbon

measurements taken since these lines were written suggest that

the present barn dates from the fifteenth century and that it incorporates

in its extant frame of timbers a few reused beams of the original barn. Cf.

UCLA Radiocarbon Dates, VI, 485 (UCLA—1057 and 1058) and

Berger, 1970, 132-33.

Hale, 1858, 122-39. For further details on these barns, most of which

are described with such accuracy that they can be reconstructed on the

drawing board, see Horn, 1958, 11ff.; and Horn and Born, 1965, 11ff.

A notable example is the great tithe barn of Harmondsworth in

Middlesex, England; see Hartshorne, 1875, 416ff.; Royal Commission

on Historical Monuments, Middlesex, 1937, 61-62; Horn, 1958, 14;

and Horn, 1970, pp. 43-46.

The practice of tithing, i.e., of drawing in a tenth of the produce of

the land the monastery owned as well as tenth of all the animals raised

on this land, was begun by Pepin III and appears to have been his means

of giving some compensation to the Church for the economic losses they

had suffered before his time under the Merovingians; cf. Ganshof,

1960, 109; and Stutz, 1908.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 3, ed. Semmler, in Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 375; and translation, III, 106.

V.14.2

THE BREWERS' GRANARY

The Monks' Brewery has its own granary with bins for the

storage of grain and other ingredients used in brewing.

This facility is attached to the south end of the House of

the Coopers and Wheelwrights and lies directly between

the Monks' Bake and Brew House and the buildings that

contain the machinery indispensable in the process of

brewing, the Drying Kiln and the Mortar. The Brewers'

Granary is a square, 32½ feet by 35 feet, internally divided

into a cross-shaped floor, which leaves four storage bins in

the corners (fig. 436).

The purpose of the building is explained by the following

title:

granarium ubi mandatu frumentum seru & ur & qđ

ad ceruisā praeparatur[469]

The granary where the cleansed grain is kept and

[where] what goes to make beer is prepared

The title implies that the grain used for brewing was subjected

to special cleaning and husking practices, which is

also suggested by the above-quoted passage from the

Statutes of Adalhard of Corbie, where it is stipulated that

the grain should be delivered to the monastery "well

winnowed and husked." The other ingredients referred

437. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 74v

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

Two men with flails thresh sheaved grain. Throughout the Middle Ages and into modern times the work of harvesting grain was done by hand

in the separate and successive steps of cutting, bundling, stacking, carting, storing, and threshing. Today these operations are performed

simultaneously by powered combine harvesters, allowing one man to reap and thresh many acres in a day; likewise, pressure balers reduce the

space required for storing straw to only a fraction of that needed in pre-industrial times. The efficient operation of this versatile machinery

spelled death to the medieval barn, the maintenance of which has become an economic liability (cf. Charles and Horn, 1973, 5ff).

reception and distribution of which, in the monastery of

Corbie, Adalhard devoted an entire paragraph.[470]

The storage bins in the four corners of the Brewers'

Granary are designated as "repositories of these same

things—likewise" (repositoria eorundem rerum—similiter).

There is no unequivocal reference to threshing in the

inscriptions of this building, unless the word seru&tur be

interpreted to imply this activity, but the cruciform shape

of the floor space left between the bins, by analogy with the

threshing floor in the large Granary, suggests that the grain

used in brewing might have been threshed in its own

granary.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. DRYING KILN, MORTAR, AND MILL

438.

6. MONKS' REFECTORY

7. MONKS' CELLAR

8. MONKS' KITCHEN

9. MONKS' BAKE & BREWHOUSE

25. GREAT COLLECTIVE WORKSHOP

26. ANNEX OF GREAT COLLECTIVE WORKSHOP

27. MILL

28. MORTAR

29. DRYING KILN

30. HOUSE OF COOPERS & WHEEL WRIGHTS AND BREWERS' GRANARY

33. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

31. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

32. KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

A. FENCE OR WALL SEPARATING "OUTSIDERS" FROM "INNER" ACTIVITIES

B. FENCE OR WALL EXTENDING TO EXTERNAL BOUNDARY

438.X SITE PLAN

The alignment of installations for grinding, crushing, and parching grain (27, 28, 29) at the southern edge of the monastry complex appears to

have been purposeful. If the topography of the site were ideal, with stream and land gradient permitting the development of water power, these

facilities on the Plan could all have been water driven. (A reconstruction of the presumptive waterways of the Plan is suggested, I, 74, fig.

53; and Horn, 1975, 228, fig. 4.

The Drying Kiln, Mortar, and Mill are sited next to the Monks' Bake and Brewhouse (9) and the Monks' Kitchen (8), and near the Bake

and Brewhouse of the Pilgrims and Paupers (32). Traffic patterns and usage demonstrated that the location of mills and mortars was carefully

planned. The Monks' Bakery and Kitchen required flour from the Mill; the Mortar produced crushed grain for brewing and for many other

dishes basic to the monks' diet. The Drying Kiln was used not only for parching grain but for drying fruit.

The noise of the mortars and mill would also have made it desirable to locate them at a distance from the center of monastic activities.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||