The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. | V. 5 |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 5

SURVIVING MEDIEVAL HOUSES

OF THE TYPE OF ST. GALL

V.5.1

EARLY EXAMPLES

The earliest extant medieval timber halls with aisles are

the hall of the castle of Leicester (fig. 339)[191]

and the hall of

the bishop's palace at Hereford[192]

(fig. 340), both from

around 1150. They are of vital importance historically

because they demonstrate that even as late as the twelfth

century the aisled Germanic all-purpose house with its

open central hearth and two inner rows of freestanding

roof-supporting posts was still a favorite form for the

representative great halls of the feudal lords of England.

That they represented the norm rather than the exception

may be inferred from the remains of other halls of like

construction[193]

as well as from an important literary source,

Alexander Neckham's (1157-1217) Summa de nominibus

utensilium[194]

in which the medieval castle hall is categorically

described as follows:

And in the hall there should be posts, set up in suitable intervals.

And furthermore there should be a full supply of nails, of slats and

of various kinds of lath, of tie-beams and of rafters reaching up to

the summit of the building. And of shorter beams there should be

enough to brace the entire roof frame.[195]

For the hall of the Bishop's Palace at Hereford, see Horn, ibid.,

9-10; and Jones and Smith, 1960.

The remains of twelfth-century halls of identical floor plan have

been found in Farnham Castle, Hertford Castle, and at Clarendon

Palace. For Farnham, see Victoria History of the Counties of England,

Surrey, II, 1905, 599-605; and Rait, 1910, 125ff. For Hertford, see

Victoria History of the Counties of England, Hertfordshire III, 1912,

501-506; and Clapham and Godfrey, 1913, 141-50. For Clarendon

Palace, see Borenius and Charlton, 1936. The prototype for all these

halls was the Great Hall, which William Rufus built in his Palace of

Westminster between 1097 and 1099. For literature on the latter, see

Horn and Born, 1965, 68 note 2.

First published by Wright, I, 1857, 103-19, after a thirteenth-century

manuscript of the Bibliothèque Nationale and Bibliothèque

Sainte-Geneviève in Paris; cf. Mortet and Deschamps, II, 1929,

181-83, where extracts are reprinted.

As published by Wright, op. cit., 109-10: "In aula sint postes debitis

intersticiis distincti. Clavibus, asseribus, cidulis et latis opus est, et trabibus,

et tignis, usque ad doma edificii attingentibus. Tigillis etiam usque ad domus

commissuram porrectis." The meaning of these terms is clarified by

Norman and Latin interlineary glosses.

V.5.2

VERNACULAR MEDIEVAL ROOF TYPES

A conspicuous innovation over their prehistoric and

early medieval prototypes, both English and Continental,

is that the walls are now constructed in masonry—at least

in the halls of the leading English feudatories. The ubiquitous

smaller manor halls of lesser but still substantial men,

continued to be built wholly in timber. Unfortunately the

two great halls of Leicester and Hereford are only of

limited use in this study. Although they present a clear

picture up to the level of the tie beams, the authenticity of

their roofs above this level has been questioned and is

uncertain.[196]

However, from the beginning of the thirteenth

century onward there is a wealth of aisled buildings with

well-preserved roofs. As one reviews this material one

finds that the vernacular medieval roof can be classified

into two basic designs, to which the German language

refers succinctly with the terms Sparrendach (literally:

"rafter-roof") and Pfettendach (literally: "purlin-roof"),

two words for which the English language has no suitable

equivalents.[197]

Intrinsically, these are the same two roof

types that Vitruvius[198]

describes as the two basic variants in

use in Rome in his day; but in contrast to the latter, which

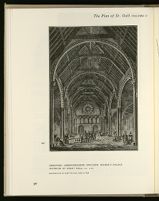

339. LEICESTER CASTLE, LEICESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND.

INTERIOR OF THE GREAT HALL, CA. 1150 [Reconstruction by T. H. Fosbrooke]

Fosbrooke views the interior of the hall as it would have appeared to one seated at the lord's table, looking down the hall to its lower end, contiguous

to the kitchen. The exact construction of the roof is uncertain, but otherwise this is a fairly accurate portrayal of the original appearance

of the building.

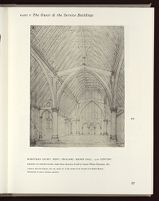

340. HEREFORD, HEREFORDSHIRE, ENGLAND, BISHOP'S PALACE

INTERIOR OF GREAT HALL, CA. 1150

RECONSTRUCTION BY John Clayton, MADE IN 1846

Hereford's interior lost its unitary quality in the 18th and 19th centuries when the bishops, searching for privacy and comfort, marred its

original appearance by inserting modern walls and ceilings. Clayton's reconstruction, controversial in some respects, nevertheless well portrays

the boldly flowing lines of this majestic interior.

The original uprights which support the roof of this hall, encased in a jumble of masonry obscuring them today, are squared oak posts, each with

round shafts attached to the four faces and terminating in scalloped capitals. The whole of each upright is hewn from a single timber. From the

capitals sprang moulded wooden arches on successive levels, in elegant and impressive spans: first across the aisles, then from pier to pier, and on

roof level, across the vast space of the nave.

This arched roof construction, as well as the design of the clustered piers and scalloped capitals, intrudes into the framework of the Nordic

timber hall features germane to the type of stone construction that occurred in the 12th century only at the highest social levels, but that became

more common later on (figs. 346, 348). For recent suggestions concerning the original design of the roof, see R. Radford, E. M. Jope, and

J. W. Tonkin, "The Great Hall of the Bishop's Palace at Hereford," Medieval Archaeology, XVII, 1973, 78-86.

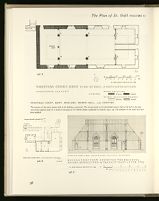

341.A CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND, ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL END OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

PLAN SHOWING THE BUILDING IN ITS FULL ORIGINAL LENGTH

Except for certain details of carpentry work (cf. fig. 356) and the superior scantling of its timbers, this building reflects a tradition that, at the

time of its construction, already spanned 27 centuries. Its plan should be compared with that of the chieftain's house at Feddersen-Wierde

(fig. 316.A, B), the cattle barn of Ezinge (figs. 298-299), and the Wohnstallhaus of Aalberg (figs. 310-311) and Elp (fig. 323). St. Mary's

shares with them the characteristic that its roof is supported by a timber frame dividing the house into a nave and two aisles, and these

internally into a multitude of separate bays, without destroying the unitary quality of the space beneath the roof.

341.B CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND. ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL. END OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

LONGITUDINAL SECTION RESTORED TO ITS ORIGINAL LENGTH

The infirmary's elongated shape owes to the same requirements that conditioned its attenuated proto- and prehistorical antecedents, i.e., the

arrangement in sequences along both sides of a common hall of a multitude of individual, but not actually separated spaces serving various

purposes—a layout ideal for communal living, Wattle walls in earlier buildings (figs. 298-299) are here replaced by masonry, obviously under

the influence of church construction—an influence even more forcefully displayed in the design of St. Mary's Gothic chapel.

A hospital dedicated to St. Mary was first founded under Henry II by Dean Williams (1158-1172) near the church of St. Mary-in-theMarket.

The present structure, separate from buildings of that original foundation, is on a site occupied until 1269 by a settlement of the Grey

Friars. In 1290 a public path running across the property was closed; this measure is generally assumed to mark the start of construction of

the present hall.

Records of gifts and deeds between 1225 and 1250, and a charter established by Dean Thomas of Lichfield (1232-1248) reveal that the hospital

was founded as a temporary home for the ill and infirm, and to provide overnight refuge for pilgrims or the wandering poor. Its original

inmates were twelve brothers and sisters forming an independent endowed community supervised by a prior or warden.

The charter did not provide for a resident priest. Support of a chaplain to be present at all canonical hours and to celebrate the hospital's

commemorative masses was founded by a separate land grant to the hospital during the tenure of Dean Thomas. The donation stipulates that

the appointment of this chaplain was to remain in the hands of the donors and their heirs; that he was to sit next to the prior and to be in

every way second only to him (in mensa et lectu et habitu). In return the donors were to be received and sustained as brothers and sisters of the

hospital for the remainder of their lives.

The charter nowhere mentions a physician to serve the hospital, which in medieval times, was for care rather than for cure, and primarily a

charitable, but not a medical facility as we understand it today (see above, 175ff). Although physicians were associated with certain medieval

English hospitals, evidence suggests that such staff positions were rare and, in general, that doctor's services were obtained for individual cases.

341.C CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND. ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL. END OF THIRTEENTH CENTURY

TRANSVERSE SECTION

The infirmary hall, seemingly more monumental than its prehistoric and early medieval predecessors, owes its appearance primarily to the

greater width and height of its bays. The roof-supporting posts rise in the corners of rectangles 27 feet wide and 20 feet deep (measured on center

of the posts) which are framed together at a height of 23 feet. The nave width, 27 feet, is just three times that of each aisle (9 feet measured

from the inner aisle wall to centers of the posts). For carpentry details of the infirmary hall see fig. 356.

In the earlier buildings, nave width only rarely reached twice that of the aisles (figs. 293-299), and in most cases was less (figs. 292, 310, 315,

and 323 in particular). But many of these earlier buildings, although narrower and not so high, were considerably longer. The larger of the

Bronze Age settlement houses of Elp were 135 feet long. The Migration Period house of Kanne (fig. 290) attained a length of 210 feet in its

final state.

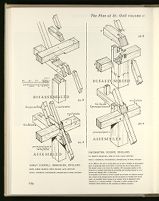

342. SCHEME OF CONSTRUCTION DRAWN IN PERSPECTIVE

ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL, CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, West,

END OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

343. INTERIOR. A PERSPECTIVE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ORIGINAL APPEARANCE

The interior view of this hall—freed of its post-medieval obstructions—should be compared with our reconstruction of the farmhouse of Ezinge,

shown in fig. 297, its senior by sixteen centuries. The carpentry of the Infirmary Hall is more accomplished, its proportions more daring, but the

principles of construction, even the spatial appearance, are the same. The aisles, formerly taken up by animals or serving as sleeping alcoves for

the farmer and his family here accommodated the beds of the ill. Like the farmhouse of Ezinge, St. Mary's was warmed by an open fireplace

in the middle of the center aisle.

In 1528 the Infirmary was transformed into an almshouse, under regulations stipulating that each resident, male or female, was to be provided

with a private room. This required the installation of individual heating units, which in their ultimate form completely marred the aesthetic

concept embodied in the hall. Yet miraculously in the course of these alterations none of the original timbers of the hall were mutilated or

altered; thus, in structural terms this reconstruction is authentic.

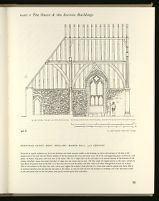

344. NURSTEAD COURT, KENT, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL, 14TH CENTURY

ABOVE: The view is from northeast; to the right lies the kitchen. As in many of its early medieval and prehistoric prototypes (see fig. 325.B),

the axis of this hall runs east to west. The door in the eastern end wall leads into a passage between pantry and larder under the hip of the roof

at the lower end of the hall. The first door in the northern long wall is in line with the kitchen, and through it the meals are served in the hall.

The door at the very end of that wall is reserved for the lord. It gives access to the dais and the private withdrawing rooms above it.

AT RIGHT: Interior view looking from the lord's table toward the lower end of the hall. Despite its vast open roof, its magnificently moulded

powerful arches, its daringly cambered cross beams, its slender king posts and sharply ascending rafters, this hall cannot conceal its derivation

from such humble structures as the farmhouse of Ezinge (figs. 297 and 327) which antedates it by 17 centuries, but with which it nevertheless

is connected in direct ancestral lineage.

DRAWING BY EDWARD BLORE, made before alteration of hall by Captain William Edmeades, 1837

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42018, FIG. 8. By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

REPRODUCED AT SIZE OF ORIGINAL DRAWING

345. NURSTEAD COURT, KENT, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL, 14TH CENTURY

DRAWING BY EDWARD BLORE, made before alteration of hall by Captain William Edmeades, 1837

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42018, FIG. 8. By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

REPRODUCED AT SIZE OF ORIGINAL DRAWING

346.A NURSTEAD COURT, KENT, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL, 14TH CENTURY

The masonry of the entire western half of the building is preserved. The reconstruction of the demolished eastern half of the hall in the plan

and section opposite (346.C) is based on drawings by Sir Herbert Baker (published in Oswald, 1933, 14). The windows in the south wall have

been modified.

346.B

[1:512]

346.C

346.D NURSTEAD COURT, KENT, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL, 14TH CENTURY

Preserved in superb condition are all of the flintstone and chalk masonry visible in this drawing, as well as the entrance to the dais at the

western end of the wall, the tall Gothic window in the bay between dais truss and center truss, all of the roof-supporting posts, arch braces, roof

plates, tie beams, king posts, and even most of the rafters. But not a single truss can be seen today in its entirety because of the insertion of two

ceilings, dividing a space once open from floor to ridge, into two stories and an attic. The floor under the hipped portion of the roof is raised one

step above the general level of the hall. It is here that the lord and his family took their meals and where distinguished persons sat at feast.

Slots in the columns of the dais truss and a center post suggest the existence along this line of a screen that could be opened and closed. But in

its vertical elevation even the dais bay was open to the rafters, as must be inferred from the presence of mouldings and other decorative motifs

on the wall plates and on the roof plates (now partly covered up by later insertions).

347.B LITTLE CHESTERFORD, ESSEX, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL, East wing about 1225, aisled hall about 1320-30,

west wing with solarium, 15th century modified in the 19th century.

PLAN AT GROUND LEVEL, EXISTING CONDITIONS (1960)

347.C

347.A

348. LITTLE CHESTERFORD, ESSEX, ENGLAND. MANOR HALL CA. 1320-30

PERSPECTIVE RECONSTRUCTION OF INTERIOR LOOKING EASTWARD

The manor hall in its ultimate form (fig. 347.B) consisted of a two-storied stone structure, built about 1225, which may have been the original

house (Smith, 1956, 83). The aisled timber hall shown above was added to this structure around 1320-30 (Smith, loc. cit.), the original house

(now east wing) being rearranged on that occasion to serve as kitchen on the groundfloor, the upper floor probably continuing to be used as

withdrawing room. A cross wing with solar (now forming the western end of the hall) was added probably in the early or mid 15th century.

Our reconstruction shows the interior of the 14th century hall as it would have appeared to one standing in the westernmost bay looking east

through the center bay with its open fireplace into the screen- bay, from which two elegant Gothic entrances lead into the interior of masonry

wing. The hall itself is now broken up into a maze of separate rooms on two levels that wholly destroys its spatial aesthetics; but enough of the

original timber frame is left to permit a tenable reconstruction: the center truss with its full complement of columns and bracing struts, and the

roof over the nave with virtually every individual piece of timber.

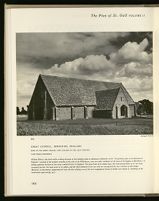

349. GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

BARN OF THE ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE OF THE 14TH CENTURY

VIEW FROM NORTHWEST

William Morris, who lived within walking distance of this building while at Kelmscott, believed it to be "the greatest piece of architecture in

England." Located in the northern stretches of the vale of the Whitehorse, some two miles southwest of the town of Faringdon in Berkshire, it is

without question the finest of the extant medieval barns in England. The great lines of its simple mass, the intersecting bodies of its two large

transeptal porches, the steep ascent of its gables, and the noble silhouette of its vast roof are unsurpassed by any structure of like design.

Moreover, in the interior, supporting the roof, this barn displays one of the most magnificent frames of timber ever found in a building of this

construction type (see fig. 351).

very steep angles.[199] We shall illustrate each of these roof

types with a few selected buildings.

THE SPARRENDACH

The Sparrendach is a roof in which a continuous sequence

of coupled rafters of relatively light scantling discharge the

load and thrust of the roof at close intervals and in equal

increments upon the walls or beams on which the rafters

were footed. The most widely known house type employing

this system is the Lower Saxon farmhouse. A closely related

variant of this roof is common in the south and southeast of

England. Zippelius has advanced some cogent arguments

in favor of the assumption that the roofs of the Iron Age

houses of the type of Ezinge, Leens, and Fochteloo belonged

to the family of the Sparrendach,[200]

and this suggests the

possibility that both the German and English variant of

this roof may have a common root in the Continental

homelands of the Saxons and their neighbors, the Frisians.

The earliest surviving domestic roof of this construction

type is, to the best of my knowledge, that of the aisled

Infirmary Hall of St. Mary's in Chichester, Sussex, which

dates from the close of the thirteenth century (figs. 341343).[201]

Although this hospital was a private foundation, its

layout follows a pattern that had been established in the

Anglo-Norman monasteries of the two preceding centuries.[202]

It consists of an oblong Infirmary Hall, originally

of six bays but now reduced to four bays, with its entrance

in the middle of the western gable wall. The eastern gable

wall opens into a masonry chapel with richly molded

Early English arches. The Hall itself is 45 feet wide, 43

feet high (clear inner measurements), and originally had a

length of 120 feet. Its roof is sustained by two rows of

wooden posts, framed together, at a height of 21 feet,

lengthwise by means of arcade plates and crosswise by

means of tie beams. The arcade plates are tenoned into a

recess in the head of the principal posts, and the tie beams

are locked into the arcade plates by means of dovetail

joints (fig. 356). The angles between the posts and their

superincumbent long and cross beams are strengthened by a

magnificent set of three-way double bracing struts of

heavy scantling which reduce the free span of the latter to

only a fraction of their total length. The rafters rise in two

flights, at the same angle, first from the wall plates to the

arcade plates, then from the arcade plates to the ridge of

the hall; those of the main roof are restrained from moving

longitudinally by a center purlin pegged into collar beams

and sustained by king posts rising from the center of each

alternate tie beam (figs. 341-342).

St. Mary's Hospital was founded as a temporary home

for the sick and the infirm who were tended by a privately

endowed community of thirteen permanent attendants

under the guidance of a prior and warden. Its elongated

shape is determined by its use as a building for attending

to the needs of a considerable number of people, including

wandering pilgrims and paupers who sought refuge for a

night only.[203]

The contemporary palace and manor halls

were shorter. A typical example of the latter with a classical

Sparrendach was the manor hall of Nurstead Court, Kent

(figs. 344-346). Judging by its architectural style, this hall

must have been built during the period when the manor of

Nurstede was in possession of the Gravensend family and

its construction is generally ascribed to Stephen de Gravensend,

who inherited the manor from his father in 1303,

became Bishop of London in 1318, and died in 1338.[204]

The

hall remained essentially unaltered until around 1837 when

in response to a need for greater comfort in living one half

of it was demolished to make room for a double-storied

structure built in the prevailing taste of the period. The

other half, likewise, was subdivided into several levels and

a variety of rooms, but here the newly inserted walls and

ceilings were suspended in the original frame of timber,

which is intact although no single part of it can be seen in

its entire height. From these remaining parts of the original

fabric and several extraordinary sets of drawings made just

before the hall was altered, by the superb architectural

draftsmen Edward Blore, William Twopeny, and Ambrose

Poynter, the original design of the hall can be reconstructed.

The hall was 34 feet wide and 79 feet long externally.

Its walls were built in flint and rose to a height of 11½ feet

With its ridge the roof reached a height of 36 feet. It was

hipped on both ends and had small triangular gables at the

peak of each hip. The supporting frame of the roof consisted

of three powerful trusses, resting on wooden columns

with molded bases and capitals and arched braces, rising

from the top of the capitals lengthwise to the arcade

plates and crosswise to the tie beams. The latter met in the

center, forming forcefully pointed arches. The tie beams

(like the other principal members, richly molded) are of

unusually heavy scantling and have sharp and elegant

camber. The roof itself is a classical example of the southern

and southeastern English Sparrendach: a continuous sequence

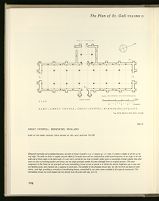

350.A GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

BARN OF THE ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE OF THE 14TH CENTURY. PLAN

Measured externally and excluding buttresses, the barn of Great Coxwell is 152′ 2″ long by 43′ 10″ wide. It reaches a height of 48 feet at the

roof ridge. The walls are built in roughly coursed rubble of Cotswold stone and are reinforced by ashlar-faced buttresses of one stage in the side

walls and of three stages in the gable walls. Its vast roof is carried by two rows of slender timber posts so successfully framed together that after

some 700 years of resisting pressure and thrust, not one single principal member has been dislodged from its original position. The main

components of this frame are six principal and seven intermediary trusses of oak so spaced as to divide the interior lengthwise into a nave and

two flanking aisles, and crosswise into a sequence of seven bays. The uprights of the principal trusses (fig. 350.B) rise from tall bases of stone

almost 7 feet high, providing a verticality of breathtaking beauty, unmatched by any other extant example of this type of construction. The

intermediate trusses are cruck-shaped and rise directly from the aisle walls (fig. 350.C).

GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

350.C

350.B

BARN OF THE ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE OF THE 14TH CENTURY. TRANSVERSE SECTION

A feature of striking beauty at Great Coxwell is the design of the three-way double braces (fig. 351) which rise from the main posts to their

connecting long and cross beams. Reducing the unsupported length of the beams that they brace to less than one third their total length, the

braces prevent them from sagging under the weight of the super-incumbent rafters. At the same time, they protect the frame from rocking and

swerving by stiffening the angles. The manner in which these braces reach out into space and assist the principal members of the supporting roof

frame to divide the interior into a sequence of separate bays may be compared to the rise and spread of the bay-dividing shafts and arches of a

medieval masonry church. It has been argued with great plausibility that this method of framing space by an all-pervasive armature of structural

members is older in wood construction than in stone (see I, 223ff).

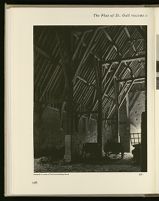

351. GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE OF 14TH CENTURY. INTERIOR LOOKING SOUTHWARD

[by courtesy of the National Buildings Record, London]

An even greater tribute than that accorded to this building by William Morris (fig. 349) was made by Thomas Hardy when in a passage of

great historical sensitivity, he wrote about a similar building in Dorsetshire:

"They sheared in the great barn, called for the nonce the Shearing-barn, which on ground-plan resembled a church with transepts. It not only

emulated the form of the neighbouring church of the parish, but vied with it in antiquity. . . . One could say about this barn, what could hardly

be said of either the church or the castle, akin to it in age and style, that the purpose which had dictated its original erection was the same to

which it was still applied. Unlike and superior to either of those two typical remnants of mediaevalism, the old barn embodied practises which

had suffered no mutilation at the hands of time" (Far from the Madding Crowd, chapter XXII).

352. PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. EXTERIOR VIEW FROM THE NORTHEAST

The grange consisted of a large rectangular yard, enclosed by a tall masonry wall. Incorporated into this wall in the south was a gate house

with a monumental round-arched passageway, and on a second level above it, a fenestrated chamber with fireplace—the dwelling doubtless of the

supervising granger. Its vast five-aisled barn, with masonry gables rising from floor to ridge, is the only surviving structure of an intricate group

of buildings once forming the inhabited nucleus of this agricultural enterprise. For á plan showing the full complement of buildings of such a

grange, made at a time when it was substantially in its original form, see Horn and Born, 1968, Pl. XIX, fig. 10.

353. PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. INTERIOR LOOKING EAST

The low pitch of the roof of this barn—distinctly different from the steep ascent of the roof of the barn at Great Coxwell (figs. 349-51)

is conditioned in part by its extraordinary width (twice that of Great Coxwell), but the decision to develop space in breadth rather than

height may have been conditioned also by climatic and cultural factors: the barn lies at the southern boundary of the area of distribution

of steep roofs.

center purlin by crown posts that rise from the middle of

each tie beam.

The westernmost bay of the hall was of two stories,

screened off against the two center bays on the ground

floor by timber screens; higher up, by a wall of plaster

reaching all the way up to the ridge of the roof. This end

served as the private quarters for the lord of the manor. The

opposite end of the hall was screened off in a similar manner

by a low timber screen with three doorways; the middle one

opened into a passage that led outside; the two outer ones,

into two rooms which could either have served as quarters

for the servants or as buttery and pantry. The kitchen was in

a separate building to the north of the hall and could be

reached from the latter through a door in the northern long

wall.

The hall of the manor of Nurstead is one of the last

examples of the traditional open hall where the lord and the

servants still lived and ate under the same roof in opposite

ends of the building—an arrangement that is very similar

to, although not identical in all details with that of the

House for Distinguished Guests of the Plan of St. Gall

(fig. 396). The two center bays of the hall were communal

space, which on festive occasions was the stage for banquets

with the open fire burning in the middle of the center

floor, as can be inferred from the smoke blackened beams

and rafters.

At the very same time England had already developed a

new plan, which provided for two double-storied cross

wings at the end of the hall, one of which served as the

private dwelling of the lord and his family; the other, as

quarters for the servants (including space for kitchen,

buttery, and pantry.) A typical example of this new arrangement

is the manor hall of Little Chesterford, Essex, a

plan and perspective reconstruction of which are shown in

figures 347-348. The hall has been ascribed by its earlier

students to about 1275[205]

and by J. T. Smith to about

1320-30.[206]

One of its aisles has been dismantled. Originally

the hall was 27 feet wide and 37 feet long. It was of three

bays with the one near the entrance serving as a narrow

screen-bay. The walls were timber framed, but all other

details were very similar to those of the hall of Nurstead

Court—less forceful and elegant, yet still of genuine refinement.

In the fourteenth century the English lowlands must

have been dotted with countless variants of this type of

hall.[207]

For the date of St. Mary's Hospital in Chichester, see Victoria

History of the Counties of England, Sussex, III, 1907, 101ff. For further

literature on this building, see Horn and Born, 1965, 47 note 24.

A comprehensive review of this material will be found in the

Master of Art thesis of Carol Anne Chazin, "The Planning of English

Monastic Infirmary Halls in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries:

A Typographical Study," University of California, Berkeley, 1965.

The original terms of the hospital are known through the records

of numerous gifts and deeds made between 1225 and 1250, and through

a charter established by Thomas Lichfield (1232-48) setting forth the

admission procedures for the establishment. The original text of this

charter (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Dept. of Western Manuscripts,

MS. University College 148, 10-11) has never been published to my

knowledge. A translation into English may be found in Swainson, 1872,

44-47.

For Nurstead Court, see Gentlemen's Magazine, 1837, 364-67;

Parker, II, 1853, 281ff; Oswald, 1933, 14ff; J.T. Smith, 1956, 84ff.

THE PFETTENDACH

The Sparrendach works with only one kind of rafter; the

Pfettendach differs from it in employing two kinds—one

of light, the other of heavy, scantling. The heavy, or

principal, rafters rise from the ends of the tie beams to the

ridge of the roof, forming powerful trusses that carry

purlins and, as a rule, a ridge piece; and it is upon these

longitudinal timbers (purlins and ridge piece) that the

lighter common rafters of the roof are mounted. In the

Pfettendach the major burden of the roof is transmitted

by the purlins to the principal trusses which discharge it

upon the walls at the beginning and at the end of each bay,

to points which, if the walls are built in masonry, are usually

reinforced by buttresses.

The best known variant of the Pfettendach is the roof of

the Early Christian basilica[208]

and all its Mediterranean

medieval derivatives. But the Pfettendach is also, as we

have seen, the standard roof in the North Germanic

territories of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland.[209]

The two earliest surviving examples of a vernacular

medieval Pfettendach are the roofs of the barn of the abbey

grange of Great Coxwell in Berkshire, a dependency of the

Cistercian Abbey of Beaulieu in Hampshire (figs. 349-354)

and the barn of the abbey grange of Parçay-Meslay, near

Tours, in France, a dependency of the monastery of Marmoutier

(figs. 352-355). The former dates from the first

decade of the fourteenth century;[210]

the latter belongs to a

group of buildings that tradition ascribes to Abbot Hugue

de Rochecorbon (1211-27).[211]

The barn of Great Coxwell (figs. 349-351) is 152 feet

long and 44 feet wide (external measurements not counting

buttresses) and reaches a height of 48 feet at the ridge. Its

vast roof rests on purlins which are held in place by

seven principal trusses sustained by posts, and six intermediate

trusses in cruck construction rising directly from

the aisle walls. The uprights of the principal trusses rest on

tall bases of stone almost seven feet high, and are framed

together 30 feet above the floor of the barn, first crosswise

by means of tie beams, then lengthwise by means of

arcade plates—a reversal of the normal and more common

procedure of housing the plates beneath the tie beams in

a recess cut into the head of the supporting posts (fig. 357).

The tall, narrow proportions of these trusses are exciting.

354.A PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. PLAN

The twelve roof-supporting trusses of the barn are not in alignment with the buttresses of the two long walls. This could be interpreted to mean

that the present frame of timber is not the original one, if this conclusion were not invalidated by the even more startling observation that the

buttresses of the two long walls fail to align with one another. An oral tradition, the precise sources of which we have not been able to identify,

claims that the original roof of the barn was destroyed by a fire in 1437 during the war with the English. Radiocarbon measurements taken of

samples extracted from two different posts did not confirm this tradition (see Horn, 1970, 28; and Berger, 1970, 111-112).

It is possible that the craftsman who built the masonry shell of the structure did not know what the carpenter had in mind; and even the

carpenter, in many cases might not have known of what number of trusses his roof-supporting frame of timber would be composed until he was

apprised of the length and strength of the available timbers. In its ultimate form the roof was composed of twelve trusses dividing the space

internally into thirteen bays each of a depth of 13 feet. The location of the buttresses would have suggested a barn of seven bays, each of a depth

of 24 feet, which is possible but structurally more risky.

354.B PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. TRANSVERSE SECTION

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the only surviving five-aisled medieval barn of transalpine Europe. There were others. The plan of the

abbey of Clairvaux and its grange of Ultra Alba (a short distance away on the opposite bank of the river Aube) records, besides two five-aisled

structures of this type, two barns that even had seven aisles. The largest among these was 210 feet long and 120 feet wide; 40 feet longer and

wider than Parçay-Meslay (for a plan and bird's-eye view see Horn and Born, 1968, Pl. XIX, figs. 10 and 11).

Since most Cistercian monasteries possessed between ten and fifteen outlying granges, the number of buildings of this kind must have been legion.

Clairvaux and Morimond counted twelve; the Abbey of Foigny fourteen; the Abbey of Fontmorigny seven; and the Abbey of Chaalis, fifteen.

On many granges, as in Ultra Alba, there were not one but two or even more such structures. Since at the beginning of the 13th century there

existed in France some 500 Cistercian monasteries, the total number of barns of this order only, and in France only, must have ranged

between 5,000 and 10,000.

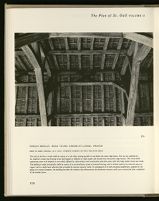

355. PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. INTERIOR LOOKING UP INTO THE ROOF RIDGE

The roof of the barn is made stable by means of a sub ridge running parallel to and below the main ridge beam. The two are stiffened by

St. Andrew's crosses (two bracing struts half-lapped at midpoint at right angles and tenoned into the paired ridge beams). This remarkable

engineering came to be adopted in and widely diffused by 19th-century steel construction some 600 years after this huge timber frame was made.

The building is made structurally stable by means of its extraordinary system of internal bracing, and is without need of an external source of

support such as might have otherwise been provided by massive masonry walls. In consequence of its self-contained equilibrium, supplied by the

genius of a master carpenter, the building provides the evidence that demonstrates the handsome masonry walls were constructed after completion

of the wooden frame.

which rise from the main posts to their connecting long

and cross beams. By reducing the unsupported length of

the beams that they brace to less than one third of their

total length, they prevent them from sagging under the

weight of the superincumbent rafters, while at the same

time protecting the frame from rocking and swerving. The

walls are built in roughly coursed rubble with buttresses of

high quality ashlar masonry. The two large doors in the

gable walls are modern. In the Middle Ages the barn was

entered broadside through two transeptal porches, one of

which had on its upper level the office of the supervising

monastic granger.

The barn of Parçay-Meslay (figs. 352-355) is quite

as impressive. It lacks the breathtaking steepness of

Great Coxwell, but its space is of a vastness that can only

be compared to that of an Early Christian basilica or of a

modern airplane hangar. It has a clear inner length of 170

feet, and a clear inner width of 80 feet. From floor to

ridge it measures 44 feet. Its vast tile-covered roof is

supported by twelve aisled trusses which divide the space

lengthwise into a nave and four aisles. The barn of ParçayMeslay

is the only example of this type to have survived

the French Revolution; but the existence of other barns

of similar design and even larger dimensions, dating from

the twelfth century, is attested by Dom Milley's engravings

of the Abbey of Clairvaux, published in 1708.[212]

It is a

purlin roof like Great Coxwell, and similar in many other

respects, but the trusses of Parçay-Meslay are more closely

spaced and are all of the same design. The assemblage of

arcade plate and post follows the more common pattern of

housing the plates in the head of the posts and locking the

tie beams into both of these members simultaneously from

above by means of dovetail joints and mortice-and-tenon

joints. The bracing struts are short and sturdy, and the

posts throughout have joweled heads.

As in Great Coxwell the purlins ride on the back of

principal rafters that run parallel to the common rafters,

a short distance farther inward (figs. 353-354). As in Great

Coxwell these inner rafters are braced by diagonal struts

that rise from the top of the tie beam. In Great Coxwell

the principal rafters over the nave terminated in the ends of

a collar beam that stiffened the corresponding pair of outer

rafters some distance below the ridge of the roof (fig. 350).

In Parçay-Meslay they are buttressed against a king post

that reaches all the way up to the ridge of the roof (fig. 354).

There are other differences. Unlike Great Coxwell, Parçay-Meslay

has no gable trusses. Instead, all longitudinal

members (plates and purlins) terminate in sockets built

into the masonry walls. A more important difference, however,

is that while in Great Coxwell a major portion of the

roof load is transmitted to the masonry of the long walls,

in Parçay-Meslay it is almost entirely absorbed in the

timber frame. The walls, of course, contribute their share

in steadying the work, but there is a complete set of outer

posts addorsed to the walls on either side of the barn, making

the timber frame virtually autonomous. In Great Coxwell

the buttresses of the masonry walls are in careful alignment

with the timber frame. In Parçay-Meslay carpenter and

mason went separate ways. No single buttress is in line

with any of the timber trusses.

One of the most remarkable features of the carpentry of

Parçay-Meslay is the measure taken, both in the lower and

upper stage of the trusses, to restrain the frame from moving

longitudinally. In the lower stage this is accomplished by

straining beams running parallel to the arcade plates, some

12 feet beneath them. They are tenoned into the posts just

below the springing of the main braces and are braced in

turn by short angle struts (fig. 353). In the upper stage of

the trusses the same task is performed by the introduction

of a sub-ridge running parallel to the main ridge, some 9

feet beneath it, and stiffened in its relation to the main

ridge by means of St. Andrew crosses (fig. 355)—a notable

piece of engineering.

The roof of Parçay-Meslay is a typical Continental purlin

roof, of a kind that is well attested through many other

Continental barns of the thirteenth century.[213]

This type

was still in use in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth

centuries as the standard form for the roof of market halls.[214]

The grange lies 9 km. northeast of Tours and ca. 1 km. north of the village of ParçayMeslay.

Marmoutier, its mother house, lay on the outshirts of Tours and slightly

upstream, on the Loire's north bank; nationalized in 1818, the abbey was then razed.

The grange at Parçay-Meslay stands as a solitary reminder of the former grandeur of

this abbey, once among the most powerful houses of Christendom.

GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

357.B

357.A

BARN, ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE 14TH CENTURY

DETAIL: ASSEMBLED, DISASSEMBLED, principal post, tie beam, roof plate

CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND

356.B

356.A

ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL, END OF THE 13TH CENTURY

DETAIL: ASSEMBLED, DISASSEMBLED, principal post, tie beam, roof plate

At St. Mary's, the roof or arcade plates are set into a shoulder of the principal

posts. A projecting tenon of the latter is mortised into the tie beam which in

this manner comes to rest above the roofplate. All converging members of the

frame are so carefully interlocked by protruding and receding elements so as to

prevent any slipping, shift, or dislocation.

In the joinery of the Barn of Great Coxwell the tie beams are likewise mortised

into a tenon of the principal posts, but the roof plates are notched over the tie

beam—an assembly which, because of its relative rarity in England is there

referred to as "reversed assembly". The latter is rather common on the

Continent. Both methods are fine examples of medieval carpentry.

Cf. above, pp. 45ff. and M. Wood, "13th-century Domestic Architecture

in England;" 1950, 1-150.

For this date see Siebenlist-Kerner, Schove, and Fletcher, "The

Barn at Great Coxwell," in Dendrochronology in Europe (forthcoming)

that supplants radiocarbon dating by Horn and Born, 1965; Horn and

Berger, 1970.

The general character of the masonry work of the barn is in full

accord with this date. There is some question, however, of whether the

present timbers of the barn of Parçay-Meslay are the original ones.

Aymar Verdier, who discussed this building in his Architecture civile et

domestique (Verdier, 1864, 37-35), reports that M. Drouet, who acquired

the barn after the French Revolution and saved it from demolition, was

of the opinion that the original frame of timber had caught fire during

the invasion of the Touraine by the English in 1437. I have no means of

judging whether this view is based on any valid historical evidence. But

even if the present timbers were proved to date from the fifteenth

century, this would have little bearing on our argument since a sufficient

number of other thirteenth-century barns survive to indicate that the

type of carpentry employed in Parçay-Meslay was widely used in the

thirteenth century; cf. Horn, 1958, 12-14.

For a good sampling of these buildings (with which Ernest Born

and I shall deal extensively in a separate study) see Horn, 1958, 13ff.

Other French thirteenth-century barns with purlin roofs are: Ardennes

(Calvados), Beauvais St.-Lazare (Oise), Canteloup (Eure), Cire-les-Mello

(Oise), Fay-les Etangs (Oise), Maubuisson (Seine-et-Oise),

Perrières (Calvados), Troussure (Oise), Vaumoise (Oise), Vaulerand

(Seine-et-Oise).

See Horn, loc. cit. Also to be considered in this context are the

market halls of Crémieu (Isère) and Questembert (Morbihan), dealt with

in Horn and Born, 1961, 66-90, and Horn, 1963.

I no longer feel as sure today of the authenticity of the roof of

Leicester Hall as I felt in 1958 (see note 1 above). With the permission

of the Leicester County Council and County Architect T. A. Collins,

Rainer Berger and I collected in 1962 and 1963 a considerable number of

timber samples from the roof trusses of Leicester Hall. These were

subsequently measured for radiocarbon content at the Isotope Laboratory

of the University of California at Los Angeles. The results of these

measurements, not known when this chapter was written, have since

been published in Horn, 1970, 59-66 and Berger, 1970, 128-29.

Radiocarbon analysis suggests that the majority of the surviving roof

trusses of Leicester Hall date from two restorations of the Norman roof,

one undertaken in the thirteenth, the other in the fifteenth century. We

could not prove that the design of the present roof is identical with that

of the Norman hall. The roof-supporting post, on the other hand, was

clearly shown to be Norman.

I am leaving out entirely the field of cruck construction, which

although more widespread than formerly believed, is in character too

regional to be considered as a third alternative in this context—and also

because the cruck truss is essentially a single span, not suited for aisled

construction. For the reader who wishes to inform himself on this

subject. I recommend the literature quoted in Horn and Charles, 1966;

as well as the more comprehensive treatment of this subject in Charles,

1967; and Charles and Horn, 1973.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||