The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. | V. 10 |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 10

MEDICAL FACILITIES

V.10.1

MEDICAL CARE AND THE WILL OF GOD

THE PHYSICIAN NOT A PRIMARY

MONASTIC OFFICIAL

Sed et vos alloquor fratres egregios, qui humani corporis

salutem sedula curiositate tractatis, et confugientibus ad loca

sanctorum officia beatae pietatis impenditis, tristes passionibus

alienis, de periclitantibus maesti, susceptorum dolore

confixi, et in alienis calamitatibus merore proprio semper

attoniti; ut, sicut artis vestrae peritia docet, languentibus

sincero studio serviatis, ab illo mercedem recepturi, a quo

possunt pro temporalibus aeterna retribui. . . .

I salute you, distinguished brothers, who with sedulous

care look after the health of the human body and perform

the function of blessed piety for those who flee to the

shrine of holy men—you who are sad at the sufferings of

others, sorrowful for those who are in danger, grieved at

the pain of those who are received, and always distressed

with personal sorrow at the misfortunes of others . . .

The Rule of St. Benedict contains no clue as to whether a

monastery was to be provided with a permanent staff of

physicians,[369]

and all later available sources disclose without

any shadow of doubt that the physician stood outside the

hierarchy of the monastery's regular administrative officers

(provost, dean, porter, cellarer, chamberlain, infirmarer,

etc.). The title carried no official status; but was granted to

monks, who by their special studies and devotion had

demonstrated unusual proficiency and knowledge in the

art of healing.

Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones, I, chap. 31, ed. Mynors, 1937,

78-79; translation by Leslie Webber Jones, An Introduction to Divine

and Human Readings, 1946, 135-36.

The term medicus appears only twice in the Rule (chaps. 27 and 28).

All that can be inferred from these occurrences is that St. Benedict held

the profession in high esteem, since in his discussion of the various forms

of punishment to be administered to unruly brothers, he equates the

wisdom displayed by an exemplary abbot with the prudence displayed

in the procedures followed by a skilled physician. Benedicti Regula,

chaps. 27 and 28, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 82-86; ed. McCann, 1952, 76-79;

ed. Steidle, 1952, 216-19.

CASSIODORUS ON THE ART OF HEALING

Cassiodorus the Senator (ca. 480-ca. 575) in a chapter

"On Doctors" of his widely read Introduction to Divine

and Human Readings, written for the instruction of his

monks some time after 551,[370]

refers to the brothers who

"look after the health of the human body" as men "who

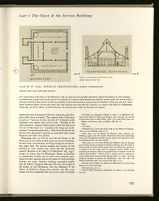

410. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE OF THE PHYSICIANS

SHOWN FULL SIZE; 1:192

The Physicians' House shares a site with the

Medicinal Herb Garden in the northeast corner

of the monastery tract. The house belongs to a

sub-group of the guest and service buildings of

the Plan, of which the communal hall is

surrounded on only three sides by peripheral

rooms. Other variants of this smaller format are

the House of the Gardener (fig. 426), the House

for Cows and Cowherds (fig. 489), and the

House for Foaling Mares and their Keepers

(fig. 487).

The proximity of the physicians to their garden

reflects the contemporary state of pharmacy,

which lay largely in the realm of botanicals, as

the authorities of Dioscurides, Isidore, and

many others attest. The physicians' duties

included compounding and dispensing medicines;

their house is provided with a secure room

especially designated for storage of medication.

may be paid for temporal acts."[371] He lists as standard

medical works to be studied for instruction in this specialized

craft: the book on herbs by Dioscurides; the Latin

translations of the works of Hippocrates and Galen (especially

the latter's Therapeutics, addressed to the philosopher

Glauco); an anonymous work compiled from various

authors; the book On Medicine by Caelius Aurelius;

Hippocrates' On Herbs and Cures as well as various other

medical treatises. He informs his readers that he had collected

copies of all of these works for future use, and that

these copies "are stored away in the recesses of our library"

(i.e., the library of the monastery of Vivarium, which he

had founded and for the monks of which the Institutiones

were written).[372]

Like the later medieval attitude toward medicine,

Cassiodorus' view about the efficacy of medical care is

tinted by the belief that the ultimate decision about sickness

and health are the concern of the Lord; and this ambivalence

between reliance on physical care and limitations

imposed upon it by divine predestination he expresses

clearly when admonishing the brothers: "Learn, therefore,

the properties of herbs and perform the compounding of

drugs punctiliously; but do not place your hope in herbs

and do not trust health to human council. For although the

art of medicine be found to be established by the Lord . . .

who without doubt grants life to men, makes them sound"

(et ideo discite quidem naturas herbarum commixtionesque

specierum solicita mente tractate; sed non ponatis in herbis

spem, non in humanis consiliis sospitatem. nam quamvis

medicina legatur a Domino constituta, ipse tamen sanos

efficit, qui vitam sine dubitatione concedit).[373]

STUDY & TRANSMISSION OF CLASSICAL MEDICINE

The Cassiodorian attitude had a profound effect on later

medieval thinking. It was responsible not only for the fact

that the science of medicine, despite its spiritual limitations

remained a highly respected avocation, but also for the

establishment of its study and transmission as a subject

worthy of being practiced in monastic schools of learning.

411. BARTHOLOMAEUS DE MONTAGNARO. CONSILIA MEDICA. 1434

A PHYSICIAN IN HIS CHAMBERS

MUNICH, BAYERISCHE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK, MS 25, FOL. lv

Montagnaro, a prominent Paduan physician, is portrayed as he inspects a flask of urine. The open books before him may be Theophilos

Unarines or the portions of Judaeus or Avicenna dealing with urine (McKinley, 1965, 13).

412. KIRKSTALL ABBEY, WEST RIDING, YORKSHIRE, ENGLAND. INFIRMARY PLAN

[redrawn after Hope and Bilson, 1907]

In its original form the infirmary hall of Kirkstall may have been very like the castle hall of Leicester, a reconstruction of which is shown in

figure 339. Pre-Norman monastic infirmaries of England were probably built entirely in timber. Under the influence of Norman church

construction, not only were the walls built in stone, but even the free-standing inner posts came to be replaced by masonry arcades. At Kirkstall

this change was made in the 14th century, in adjustment to a trend that in other places such as Canterbury (I, 70, fig. 52.A) had begun as early

as mid-11th century.

of these skills was held in high esteem. The oldest

catalogue of the library of the Abbey of St. Gall lists no

fewer than six medical treatises.[374] The Abbots Grimoald

(841-872) and Hartmut (872-883) increased these holdings

by each bequeathing to the monastic library one medical

book.[375] Among the actually surviving medical treatises of

St. Gall, written in the ninth century, there are extracts

from the works of Hippocrates and Galen (Cod. 44), a book

on cures through herbs and animal extracts (Cod. 217), a

large collection of medical prescriptions (Cod. 751), a

heavily used list of pharmaceutical prescriptions (Cod. 759),

as well as a collection of smaller medical treatises written

by the hand of an Irish monk.[376] Abbot Grimoald (841-872)

can be singled out as one who apparently took a special

interest in the art of healing, since it is to him that Walahfrid

Strabo dedicated his famous poem, Hortulus, in which the

virtues of medicinal herbs are extolled.[377] Other monks of

St. Gall reputed to have been physicians of great distinction

were Iso and Notker II, surnamed Medicus. Iso is

praised by Ekkehart IV for his skill at making salves and is

reported to have healed blind men, lepers and paralytics

with his ointments.[378] The same author proclaims Notker II

the most famous of all.[379] Frequently performing unbelievable

wonders of healing, he was known far and wide in the

country as one of the greatest monastic urologists.[380] The

names of other monks skilled in this science are listed in the

Necrologium of St. Gall.[381]

See Meyer von Knonau's remarks to chap. 31 in Ekkeharti (IV.)

Casus sancti Galli, ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 124 note 422 and the

sources there cited; as well as Meier, 1885, 116-17 and Clark, 1920, 126.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 31. ed. Meyer von Knonau.

1877, 124; ed. Helbling, 1958, 71-73.

Ibid., chap. 123, ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 398-401; ed.

Helbling, 1958, 205-6. For further information about this outstanding

monk, who distinguished himself as poet, painter and musician as well,

see Helbling's index sub verbo Notker.

Ibid., chap. 123. It is of this Notker that Ekkehart tells the amusing

story (widely quoted in histories of medieval medicine) how the Duke of

Bavaria tried to test his medical perspicacity by sending him, instead of

a sample of his own urine, that of a pregnant woman. Notker, after

examining the sample, without any apparent sign of suspicion made the

solemn announcement: "God is about to bring to pass an unheard of

event; within thirty days the Duke will give birth to a child." On early

medieval medicine in general, see MacKinney, 1937 and 1965. On

Notker specifically, idem, 1937, 45-46; and 1965, 13-14.

See the notes of Meyer von Knonau in Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti

Galli, op. cit., 401, note 1435.

V.10.2

HOUSE OF THE PHYSICIANS

Besides the Monks' Infirmary and the sick ward in the

Novitiate,[382]

the Plan provides for three other medical installations:

the House of the Physicians, the Medicinal

Herb Garden, and the House for Bloodletting, all of which

are situated in the northeast corner of the monastery next

to the Monks' Infirmary. The House of the Physicians (fig.

410) forms the center of the group. It is separated from the

House for Bloodletting by a wall or fence and has no direct

connection with the Infirmary. The house is small and

almost square in shape (37½ feet by 42½ feet). Its principal

room is designated as "the hall of the physicians" (domus

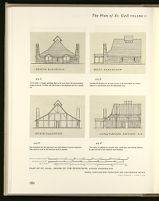

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE OF THE PHYSICIANS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

413.A

413.B

GROUND PLAN AND TRANSVERSE SECTION

Our reconstruction of the House of the Physicians is only one choice of several possible alternatives. Despite the inclusion of corner fireplaces

in the physicians' private aisle and the aisle for the critically ill—a feature which elsewhere has called for masonry walls—the exterior walls of

this house could have been entirely of timber (a possibility we have demonstrated in reconstructing the Gardener's House, figs. 427.A-F, where

similar conditions obtain). On the other hand, these walls could also have been built all in masonry, as is shown in the House for Distinguished

Guests (figs. 397.A-F). Above is a third alternative: the entrance wall is timber, all the others are masonry.

with louver overhead. The western aisle of the house

is used as a "bedroom for the critically ill" (cubiculum ualde

Infirmorum); the eastern aisle serves as the "dwelling of the

chief physician" (mansio medici ipsius), while the lean-to in

the rear of the house is a "repository for drugs and medicaments"

(armarium pigmentorum). Both the bedroom for the

sick and the physician's quarters are provided with corner

fireplaces and their own privies.

Measuring only 37½ feet by 42½ feet the House of the

Physicians is one of the smaller guest and service buildings.

Its sick room, nevertheless, was large enough to accommodate

eight beds. We should imagine the interior of this

building to have looked very much like the thirteenth

century Hospital of St. Mary's in Chichester, (fig. 343),[383]

except, of course, that the Physicians' House on the Plan

is considerably smaller and its aisles were probably separated

from the common hall in the center by wall partitions

between the posts. Another building, somewhat smaller

than St. Mary's Hospital although still twice the length of

the House of the Physicians, was the Infirmary of the

Abbey of Kirkstall, dating from around 1220 (fig. 412),

whose roof was originally held up by two rows of wooden

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE OF THE PHYSICIANS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

413.C

In the center: a window admitting light to the room where the pharmaceutical

drugs are stored. To either side: the privies of the physicians and the critically

ill.

413.D

Our assumption that the gable walls were half-timbered is purely conjectural.

They could of course as well have been built in masonry.

413.E

Locating the fireplaces in the outer corners of the aisles keeps the chimney

stacks at a safe distance from the inflammable roof.

413.F

Two trusses, in addition to the gable walls, would have been entirely sufficient

to carry the roof of this relatively small building.

NORTH, SOUTH AND WEST ELEVATIONS AND LONGITUDINAL SECTION

SCALE 1/16 INCH = 1 FOOT [1:192]

House of the Physicians on the Plan is the Carolingian

prototype for this type of building.

It is one of only a few buildings on the Plan in which the

main room with the open fireplace is directly accessible

from the outside.[385]

We have reconstructed this side of the

house as a straight timber-framed gable wall (fig. 413A-F),

with infillings of daubed wattlework, reaching to the

ridge of the roof. Because of the presence of corner

fireplaces in the physician's bedroom and in the room for

the critically ill, we have rendered the walls against which

these fireplaces were built in masonry. The architectural

privacy of both the physicians and their critical patients—

attainable only by wall partitions and ceilings separating

their quarters from the common source of light and air in

the center room—created, of course, a need for supplementary

fenestration in the walls of these rooms.

The isolated location of the House of the Physicians and

its rigid separation from all other buildings have given rise

to the opinion that it served primarily as an isolation ward

for patients with communicable diseases.[386]

It appears to me

more plausible to assume that it was the place where the

monastery's serfs and workmen were taken when their condition

became critical, since laymen could not be admitted

to the Monks' Infirmary. The monks had their own ward

for persons stricken with acute illness, and this could also

have been used as a separation ward for monks afflicted

with communicable diseases.

The physicians were obviously not only in charge of the

patients who were bedded in the Physician's House, but

also attended to the sick in the adjacent Infirmary of the

Monks and took care of the treatments administered in the

House for Bloodletting. That they were not always from

the ranks of the regular monks may be gathered from Abbot

Adalhard's Directives for the Abbey of Corbie, where two

physicians (medici duo) are listed as laymen.[387]

Hildemar, in

his commentary on the Rule, lists as instruments indispensable

to the physician: the bloodletting tools (fleuthomus),

the book of herbs (herbarius liber), the medicaments and

tools required for their preparation (pigmentum ferramenta

quibus incidit), and "all such other similar things with the

aid of which the physician performs his craft of healing"

(et reliqua his similia, quibus medicamen medicus operatur).[388]

For the Infirmary of Kirkstall Abbey, see Hope and Bilson, 1907,

38-43. The Infirmary Hall of Kirkstall Abbey was 83 feet long; its nave

had a width of 31 feet, and the aisles, each a width of 11 feet. The main

entrance lay in the western gable wall; another smaller door gave access

through the southern long wall. In the easternmost bay of the north aisle

there was a large fireplace which may have been used for cooking, as the

kitchen was some distance away. The existence of wooden posts in the

original building can be inferred from the sockets in the original stone

bases that supported these posts. Some of these bases are preserved.

Others are the House of the Gardener and His Crew, see below,

pp. 203ff; the House of the Cows and Cowherds, see below, pp. 279ff;

the House for the Foaling Mares and Their Keepers, see below,

pp. 287ff.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 1, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 367; and translation, III, 103.

V.10.3

MEDICINAL HERB GARDEN

The medicinal herb garden (herbularius) lies in the northeastern

corner of the monastery site, immediately east of

the House of the Physicians. It is a small intimate garden,

37½ × 27½ feet (fig. 414). Like the Monks' Vegetable Garden,

it is surrounded by a wall or a fence, but the arrangement

of the planting beds differs. In the Vegetable Garden

the planting beds are separated from the walls by a peripheral

walk, so that each bed can be cultivated from all four

sides. In the medicinal herb garden a row of planting beds

clings to each wall. This seemingly insignificant rearrangement

of beds in relation to the wall is, according to Wolfgang

Sörrensen, the first step away from the "utility garden"

(Nutzgarten) to the "pleasure garden" (Ziergarten).[389]

It

would, nevertheless, be wrong to classify the herb garden

on the Plan of St. Gall as a "Ziergarten." The primary

function of its plants is a practical one: they furnish the

physician with the pharmaceutical products needed for his

cures. As in the Monks' Vegetable Garden, each planting

bed is reserved for the cultivation of a single species. There

are sixteen in all:

| 1. | lilium | lily (lilium candidum L.) |

| 2. | rosas | garden rose (rosa gallica L.) |

| 3. | fasiolo | climbing bean (dolichos melanophtalmus L.) |

| 4. | sata regia | pepperwort (satareia hortensis L.) |

| 5. | costo | costmary (tanacetum blasamita L.) |

| 6. | fena greca | greek hay (trigonella foenum graecum L.) |

| 7. | rosmarino | rosemary (rosmarinus officinalis L.) |

| 8. | menta | mint (mentha piperita L.) |

| 9. | saluia | sage (salvia officinalis L.) |

| 10. | ruta | rue (ruta graveolens L.) |

| 11. | gladiola | iris (iris germanica L.) |

| 12. | pulegium | pennyroyal (mentha pulegium L.) |

| 13. | sisimbria | water cress (mentha aquatica L.) |

| 14. | cumino | cumin (cuminum cyminum L.) |

| 15. | lubestico | lovage (levisticum officinale L.) |

| 16. | feniculum | fennel (anethum foeniculum L.)[390] |

A charming contemporary description of a garden of this

type is Walahfrid Strabo's Hortulus, written around 845 in

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MEDICINAL HERB GARDEN

414. PLAN OF ST. GALL. MEDICINAL HERB GARDEN

414.X

414.Y

PLOT PLAN

SHOWING RELATIONSHIP OF HEALTH & MEDICAL FACILITIES

The plot plan suggests two traffic patterns within the Infirmary areas. Moving

north, monks and serfs needing medical attention could leave the Church after

services and report to whichever medical facility they were assigned. The

Monks' Infirmary was available only to regular monks; the House for

Bloodletting was probably used by both monks and serfs. The critically ill were

lodged with the physicians; probably serfs or other laymen with minor infirmities

were treated where they lodged.

Moving southward on the site, the physicians might make daily rounds:

conducting or overseeing bloodletting; at the bath and kitchen for the ill

recommending therapy and special diet, supplies for which might be sent for

from the small stock of luxuries afforded the Abbot in his own nearby kitchen;

thence reporting directly to the Abbot himself (as was their charge and his own)

concerning the ill, recommending further treatment for some, or swifter cures for

suspected malingerers. At mid-point in this course the physicians could stop in

the Chapel and Cloister for the Ill to advise recuperating brothers.

It would be an oversight to regard these economies of movement and communication

as happy accidents; on the contrary, a high degree of skill and

consciousness in such matters helped the Benedictines eventually to influence

the affairs of Carolingian Europe, and gave the Plan of St. Gall its unique

stature as an architectural plan.

The herbs to be cultivated in this small garden are selected for their medicinal properties. Their renascence each spring under the care of man,

after the plants had either died altogether or only back to their roots during winter, has been described by Walahfrid Strabo in an account of

great poetic beauty (Hortulus) as a recurring manifestation of the forces of life imparted to nature by Divine creation.

The physicians cared directly for the critically ill and for those to be bled; their chief duties in addition were making medicines, and prescribing

courses of treatment that might be administered by others. From the nearby garden they could pluck fresh the plants needed to compound the

poultices, purges, infusions, and simples that were the main concerns of pharmacy in the 9th century.

415. MEDICINAL HERB GARDEN. PERSPECTIVE VIEW FROM THE NORTHEAST (INTERPRETATION)

Areola et lignis, ne diffluat, obsita quadris

Altius a plano modicum resupina levatur.

Tota minutatim rastris contunditur uncis,

Et pinguis fermenta fimi super insinuantur.

Seminibus quaedam tentamus holuscula, quaedam

Stirpibus antiquis priscae revocare iuventae.

Denique vernali interdum conspergitur imbre

Parva seges, tenuesque fovet praeblanda vicissim

Luna comas. . . .

Then my small patch was warmed by winds from the south

And the sun's heat. That it should not be washed away,

We faced it with planks and raised it in oblong beds

A little above the level ground. With a rake

I broke the soil up bit by bit, and then

Worked in from on top the leaven of rich manure.

Some plants we grow from seed, some from old stocks

We try to bring back to the youth they knew before.

Then come the showers of Spring, from time to time

Watering our tiny crop, and in its turn

The gentle moon caresses the delicate leaves.

WALAHFRID STRABO, HORTLUS, verse 46-55

Payne and Blunt, eds., 1966, 28-29

early spring he rushes into this garden, weeds out the nettles,

and covers the soil with manure which he carries out in

baskets. As soon as the soil is permeated with the fermenting

action of this substance and fanned by the warm winds

from the south, he turns it over with the spade, and

frames the planting beds with boards to prevent the humus

from sliding off onto the walks. Then he sets out his seedlings

and in the following weeks observes with empathy

the miracle of nature's rejuvenation in the growth of plants

whose shape and physical characteristics he describes with

a sharpness of visual definition that reminds one of the

much later plant and water studies of Albrecht Dürer.

Nine of the sixteen plants listed in the herb garden on

the Plan were also grown in Walahfrid Strabo's garden. All

of these plants, as botanists stress, could be raised in the

warm climate of the island monastery of Reichenau,[392]

and

all of them, with the exception of pumpkin and melon, had

medicinal value. In the cultivation of these gardens and the

medical uses to which they were put, the monks leaned

heavily on the classical tradition. But they did not expand

just the traditional medical use of plants and herbs; the

benefits they brought to the art of cooking may have surpassed

the contributions their gardens made to medicine.[393]

From the monasteries the use of herbs spread to the nobles

and the peasants, and thus, eventually, herbs became an

integral part of every kitchen garden.[394]

Fish which are fatty by nature, like salmon, eels, shad (alase), sardines, or

herring, are caught, and this mixture is made from them and from dried

fragrant herbs and salt: a very solid and well-pitched vat is prepared, holding

three or four modii, and dry fragrant herbs are taken both from the garden and

the field, for instance, anise, coriander, fennel, parsley, pepperwort, endive,

rue, mint, watercress, privet, pennyroyal, thyme, marjoram, betony, agrimony.

And the first row is strewn from these in the bottom of the vat. Then the

second row is made of the fish: whole if they are small, and cut to bits if large.

Above this a third row of salt two fingers high is added, and the vat should

be filled to the top in this manner, with the three rows of herbs, fish, and salt

alternating each over the other. Then it should be covered with a lid and left so

for seven days. And when this period is past, for twelve days straight the mixture

should be stirred every day clear to the bottom with a wooden paddle

shaped like an oar. After this the liquid that has flowed out of the mixture is

collected, and in this way a liquid or sauce [?; omogarum] is made from it. Two

sesters of this liquid are taken and mixed with two half sesters of good wine.

Then four bunches [manipuli] a piece of dry herbs are thrown into this mixture,

to wit, anise and coriander and pepperwort; also a fistful of fenugreek seed is

added, and thirty or forty grains of pepper spices, three pennyweights (?) of

costmary, likewise of cinnamon, likewise of cloves. These should be pulverized

and mixed with the same liquid; then this mixture is to be cooked in an iron

or bronze pot until it boils down to the measure of one sester. But before it is

cooked down, a half pound [libram semissem] of skimmed honey should be

added to the same. And when it is fully cooked in the manner of a drink [more

potionum] it should be strained through a bag until it is clear. And it should

be poured hot into a bag, strained and cooled and kept in a well-pitched bowl

for seasoning viands.

Recipe quotation after Mitteilungen der antiquarischen Gesellschaft,

Zürich, XII, No 6; Bikel, 1914, 99-100.

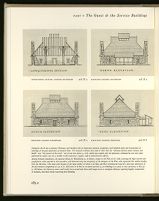

416. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR BLOODLETTING

In the Middle Ages bleeding was used to remedy almost every known disease, to such excess that public opinion eventually turned against the

procedure. It is, even today, used as a cure for a small number of pathological conditions where other means fail—but nowhere, now, to the

extent of justifying the construction of special houses for bleeding. The Plan of St. Gall reveals with unique precision the appearance of this

extinct species of house in the 9th century.

"Die vier Wände stehen nicht kahl ringsum, sie werden vielmehr

von dem schönen Wachstum der Beete gekränzt, sodass der Wandelnde,

wo er auch sein mag, von Beeten umgeben, gleichsam eingehüllt ist."

On this aspect of monastic gardening and planting, see Sörrensen, in

Studien, 1962, 241-43 and 263ff.

The modern Latin plant names listed in parentheses are taken from

Wolfgang Sörrensen's article on the plants of the Plan. See Studien,

1962, 223ff.

Walahfrid Strabo, Hortulus, ed. Dümmler, in Mon. Germ. Hist.,

Poetae Latini Aevi Carolini, II, 1884, 335ff; and ed. Näf and Gabathuler,

1957.

For the history and medicinal functions of these plants, I refer to the

detailed accounts of Sierp (1925, passim) Fischer (1929, passim), Sieg

(1953, passim), and Sörrensen in Studien, 1962, passim.

The pains that were taken in the preparation of certain potions

made from these herbs border on the unbelievable. In illustration of this

is a recipe for a seasoning substance, described in a manuscript of St.

Gall, which I cannot resist bringing to the attention of the reader, since

it is published in a journal not available to many:

V.10.4

HOUSE FOR BLOODLETTING

DESCRIPTION OF HOUSE

fleotomatis hic gustandum ʈ potionariis[395]

Here is the place for bloodletting and for purging

The House for Bloodletting (fig. 416) lies west of the

Physicians' House and consists of a large rectangular space

35 feet by 45 feet. It is furnished with a central fireplace

with the customary louver and contains, besides this traditional

heating device, four additional corner fireplaces

as well, doubtless in consideration of the weakened condition

of the monks after being bled. The wall space between

these fireplaces is taken up by six benches and tables

(mensae) on which the monks were bled and purged.

The primary function of this separate house, as Leclercq

has correctly pointed out, is to relieve the Monks' Infirmary

of the many people who were to receive the incision of the

lancet as a cure for a vast variety of ailments, real and

imaginary.[396]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR BLOODLETTING

The vulnerable condition in which patients found

themselves through the process of bleeding

required that the House for Bloodletting be well

heated. This was accomplished by installation of

four corner fireplaces, in addition to the traditional

open fireplace in the center of the building. Safety

from fire hazards would require that the walls of

the House for Bloodletting be built in masonry.

416.X.2 TRANSVERSE SECTION LOOKING EASTWARD

Without doubt Carolingian builders could have

covered a house 35 feet wide with a single span

(the nave of the Church after all had a span of 40

feet) but in most medieval buildings such a span

would have had additional support in two rows of

free-standing inner posts, if more than 25 feet

wide. For this reason in our reconstruction we have

introduced four additional inner posts carrying

roof plates, which in the longitudinal direction of

the building are slightly cantilevered to support the

rafters of the hips of the roof.

416.X.1 PLAN AT GROUND LEVEL

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

416.X.3 LONGITUDINAL SECTION, LOOKING SOUTHWARD

416.X.5 ELEVATION LOOKING NORTHWARD

416.X.4 ELEVATION LOOKING SOUTHWARD

416.X.6 ELEVATION LOOKING WESTWARD

Caring for the ill was a primary Christian, and therefore also an important monastic occupation, and included study and transmission of

teachings of the great physicians of classical times. Yet monastic tradition also made it clear that the "ultimate decision about sickness and

health" was "the concern of the Lord," not of man (see above, p. 176), which may explain why the physician, although his arts were often

performed by monks, was not a member of the monastery's regular staff of administrative officers.

Among monastic foundations, the separate House for Bloodletting is, we believe, unique to the Plan of St. Gall, attesting the high curative and

prophylactic value attached to this procedure, and demonstrating the perspicuity of the designers of the Plan, who separated this medical facility

from the infirmary. This made sense because of the large number of monks to be bled, and their convalescent state for a few days afterward. If

the full monastic complement of 130 at St. Gall were to be bled at six-week intervals (1,170 bleedings in a year) as was customary at Ely (cf.

p. 188 below), the Infirmary alone could hardly have served both those with longer-term or contagious illnesses requiring lengthy recuperation

or isolation, and those merely recovering from bleeding.

417. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS 42130, FOL. 61

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

A physician bleeds a patient under the interested gaze of a large kingfisher. The iconography of this bird is ancient and complex; with its

ability to hurl itself into the water and then arise after having apparently drowned, it captured the Christian imagination to become a symbol

for the resurrected Christ. Perhaps its association with the act of bleeding symbolizes the hope of the patient for restored health.

Fleotomatus is a common medieval form for classical Latin phlebotomatus,

from Greek φλεβοτομεῑν, "to open a vein" and φλεβοτομί α,

"bloodletting." The ῑ between gustandum and potionariis was correctly

transcribed as vel by Keller, 1844, and all subsequent writers. Cf.

Battelli, 1949, 110.

MONASTIC VIEWS ON BLEEDING

The Rule of St. Benedict is silent on the subject of

bleeding,[397]

and there is no certainty as to what point in

history bleeding became a regular practice in monastic life.

A description in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of a case of

unsuccessful bloodletting causing intensive swelling and

nearly leading to the death of a nun, suggests that bleeding

was a fully adopted form of medical treatment in the

monasteries of England at the time of Theodore of Tarsus

(669-690). The same story also reveals that when something

went wrong with the operation this was likely to be

attributed not to the use of infectious tools or other forms

of medical malpractice, but to the fact that the operation

was performed at the wrong time: "You have acted

foolishly and ignorantly to bleed her on the fourth day of

the moon," Bede records Bishop Wilfrid of Hexham to

have exclaimed. "I remember how Archibishop Theodore

of blessed memory used to say that it was very dangerous

to bleed a patient when the moon is waxing and the Ocean

tide flowing. And what can I do for the girl if she is at the

point of death?"[398]

A book, De minutione sanguis, wrongly

attributed by tradition to the Venerable Bede, recommends

that the blood be let between March 25 and May 26, on the

assumption that this was the season "during which the

blood develops in the human organism" (quia tunc sanguis

augmentum habet). After this period, the operation was to be

undertaken only with a due regard for the qualities of

the seasons and phases of the moon (sed postea observandae

sunt qualitates temporum et cursus lunae).[399]

The first synod of Aachen (816) abolished the custom

according to which large segments of the community were

bled at a fixed date, and ruled that individuals be bled

according to need. It reaffirms the right of those who are

exposed to this treatment to receive a fortifying diet of food

and drink, including at least by implication the otherwise

forbidden meats (Ut certum fleutomiae tempus non obseruent,

sed unicuique secundum quod necessitas expostulat concedatur

et specialis in cibo et potu tunc consolatio prebeatur).[400]

The food for the monks who were bled was doubtlessly

prepared in the kitchen of the Infirmary, which lies directly

to the west of the House for Bloodletting. The number and

length of the tables in this house would permit the simultaneous

feeding of a maximum of thirty-two monks, if we

count 2½ feet as the normal sitting space required by each

monk, as we did in calculating the seating capacity of the

Monk's Refectory.[401]

The number of monks to be bled on

a single day could not exceed this figure; and if as many as

thirty-two were bled in a single day, this operation could

not have been extended to others, until the first group to be

treated had gone through the entire cycle of convalescence,

which involved several days of special treatment and care.

418. GRIMANI BREVIARY (1490-1510). ILLUMINATION FOR THE MONTH OF SEPTEMBER

VENICE, BIBLIOTECA DI SAN MARCO, FOL. 10

The breviary affords a painfully realistic view of a physician bleeding a patient. The Grimani Breviary, of uncertain authorship, provenance,

and even date, is one of the finest and most profusely illuminated manuscripts of its class; its 110 illuminations depict labors of the months and

numerous other scenes from daily life, religious festivals, feasts of the saints. The illuminations are from many different hands, mostly Flemish,

a few perhaps French; the style suggests a date nearer the start of the 16th century.

The word flebotomatus does not occur in the Rule; see the index of

words in Benedicti regula, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 175ff.

"Multum insipienter et indocte fecistis in luna quarta flebotomando.

Memini enim beatae memoriae Theodorum archiepiscopum dicere, quia

periculosa sit satis illius temporis flebotomia, quando et lumen lunae, et

reuma oceani in cremento est. Et quid ego possum puellae, si moritura est

facere?" Bede, Hist. Eccl., book V., chap. 3, ed. Plummer, I, 1896, 285;

ed. Colgrave and Mynors, 1969, 460-61. (The passage was brought to my

attention by C. W. Jones.)

De minutione sanguis, ed. Migne, Patr. Lat., XC, 1862, cols. 959-62.

With regard to the wrong attribution of this treatise to Bede see Jones,

1939, 88-89.

Synodi primae decr. auth., chap. 10, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 459-60. The matter had already been taken up in the preliminary

deliberation of this synod and had elicited some interesting remarks by

Bishop Haito: See Statuta Murbacensia, chap. 12, ed. Semmler, op. cit., 445-46.

MEDIEVAL PORTRAYALS OF BLEEDING

A marginal illustration in the Luttrell Psalter (fig. 417)

furnishes us with a realistic picture of the performance of

this ubiquitous craft. It shows a physician standing and

bleeding a patient from the right arm. The patient is seated

on a stool and holds a bowl in his left hand to catch the

blood. He keeps his right arm steady by propping it on a

staff or pole while the physician places his left foot on that

of the patient. This appears to have been a standard position

for this kind of operation. It occurs again, almost

feature by feature, in the representation of a similar scene

in the Grimani Breviary (fig. 418).[402]

In both cases the blood

is taken from the anticubital vein, in the crook of the elbow,

a preferred place for bloodtaking even today, since here one

of the principal veins comes close to the surface and exposes

itself in a relatively fixed position. The staff or pole, apart

from steadying the patient in a general sense, adds muscular

control to the operation, as it enables the patient to

increase or diminish the flow of blood by locking his fist

around the pole or conversely by relaxing his grip.

For the Luttrell Psalter, see Millar, 1932, pl. 16; for the Grimani

Breviary, see Morpurgo and de Vries, I, 1903, pl. 18.

PHLEBOTOMY: A MEDIEVAL PANACEA

Phlebotomy was a medical omnium-gatherum used for

curing a bewildering variety of ailments.[403]

The Regimen

sanitatis salernitanum, a widely read treatise on medicine,

written at the end of the eleventh century for Robert, Duke

of Normandy, the eldest son of William the Conqueror,

probably by John of Milan, head of the faculty of the School

of Medicine of Salerno at that time,[404]

defines its beneficial

effects as follows:

Phlebotomy clarifies the eyesight, strengthens mind and brain. It

warms the marrow, purges the intestines, forces stomach and

bowels into action. It purifies the senses, induces sleep, gives relief

from boredom. It restores and strengthens hearing, voice and

energy, facilitates speech, appeases ire, allays anxieties, and cures

watering eyes.[405]

The physician points out that the "superabundance of

spirit" (spiritus uberius) that escapes with the blood is

quickly replenished through the drinking of wine, while

the weakness of the body sustained by bleeding is gradually

repaired by the intake of food.

For a general review of the practice of bloodletting, see MacKinney,

1937, 39ff., and Gougaud, 1930, 49-68.

For date and authorship, see Packard's introduction to Regimen

sanitatis salernitanum, 1920, 24ff.

My prose translation follows the text published by Saint-Marc,

1880, 213-14, which is a little longer than the text published by Packard,

op. cit., 176.

FROM PHYSICIAN TO BARBER

There is no reason to presume that in the early Middle

Ages bloodletting was performed by persons other than

trained physicians. Alcuin and Walahfrid Strabo refer to

the practice as being performed by medici.[406]

But in the later

Middle Ages physicians considered this operation to be

beneath their dignity and conceded it to "barbers" and

"professional bleeders" (rasatores et sanguinatores).[407]

In the

twelfth century this change must have been well under way.

A hint of the social milieu from which such secular bleeders

may have emerged and how and where they may have

received their training is found in the Chronicle of the

Abbey of St. Trond, where it is said of one of the monastery's

serfs, a recalcitrant oppidanus (inhabitant of a city)

named Arnulf, that in return for the terms of a tenement

granted to him by the abbey, he was not only to assist the

monks whenever they were bled, but in addition to provide

for the abbot's saddle and spurs, repair the abbey's window,

and perform other minor services, such as keeping all of

the monastery's locks in working condition.[408]

Rudolfi Gesta abbatum Trudonensium, Book IX, chap. 12, ed,

Koepke, in Mon. Germ. Hist., Scriptores, X, 1852, 284. The passage

refers to the period 1108-32: "Oppidanus quidam noster Arnulfus nomine

patris quod sui Baldrici imitatus violentiam, terram tenera volebat sine

servitio, quae debet servire fratribus ad omnem minutionem sanguinis

eorum debet et alia minuta servitia ad utensilia camerae abbatis,

scilicet quicquid de ferro ad sellam equitariam eius et ad calcaria et ad

saumas componitur, dato sibi ab abbate ferro. Fractas vitreas fenestras

monasterii, claustri, cellae abbatis, accepto et custode vitro, plumbo et

stagno et caere et sumptu emendat. Claves omnes monasterii et scriniorum,

dato sibi ferro, novat et renovat, similiter et de omnibus officinis claustri et

curtis.

RELIEF FROM DREARINESS OF DAILY ROUTINE

Dom D. Knowles attributes the phenomenal spread of

the practice of bloodletting in monastic life to the "general

feeling of physical malaise" brought about by an unbalanced

diet and the sedentary life of the monks, calling for

some violent form of relief.[409]

One of the attractive features

of its practice was that it gave relief from the dreariness of

the daily routine and was associated with a fortifying regime

of food, allowed in compensation for the loss of blood. This

gave to the occasion a touch of recreative pleasure, which

monastic discipline found it difficult to repress.

RULES TO BE FOLLOWED IN THE PRACTICE

OF BLEEDING

A detailed account of special rules to be followed in the

practice of bleeding will be found in Ulric's Antiquiores

consuetudines (d. 1093) of the Monastery of Cluny[410]

and the

chapter "Permission for Being Bled" in the Monastic

Constitutions of Lanfranc.[411]

From a review of these, and a

variety of other sources,[412]

the routine of the monk who subjected

himself to bloodletting went as follows:

After having obtained formal permission to be bled

(licentia minuendi) by petition to the chapter, the brother

left the church at the end of the principal mass and went to

the dormitory to exchange his vestments of the day (diurnales)

for his clothing of the night (nocturnales) which he

retained for the three days of rest that followed his operation.

The operation was initiated with a brief prayer which

began with the verse Deus in adjutorium meum intende. (In

the Benedictine monastery this prayer was preceded by an

inclination of the body called ante et retro.) The incision

was made in the morning, save for the time of Lent, when

it was done after vespers. The patients were issued bandages

of linen (fasciae, ligaturae, ligamenta brachiorum, bendae,

arcedo) with which to wrap their arms. Some consuetudinaries

recommend that before being bled a monk should

pass by the kitchen to have his arm warmed.

During recovery the patients were not held to their

regular duties in the choir, but had leave to rise later than

the others and to recite only a part of the divine office.

Moreover, they were at liberty to take walks in the monastery's

vineyards and meadows. Their diet, as already

mentioned, made allowance not only for the ordinarily forbidden

meats, but also for greater abundance. During the

periods when the rest of the community ate only one meal,

the frater minuendus ate two; on all other occasions, three:

the mixtum, the prandium and the coena.

It is obvious that in view of all these special privileges,

bloodletting acquired an attraction that in the minds of

some of the more conservative members of the community

bordered on dissipation; and the monastic consuetudinaries,

indeed, abound with admonitions aimed at curtailing

the spread of merriment, if not of outright breaches of

discipline, with which this activity tended to be associated.

A main concern of those who were in charge of monastic

discipline was to prevent the seynies from coinciding with

important religious festivities; others felt it necessary to

restrict the repetition of the privilege to certain cycles. The

monastery of St. Augustine in Canterbury allowed the

monks to be bled in intervals of seven weeks; at Ely the

interval was six; in other monasteries it was only five or

four times per year that a monk could be bled.

The reconstruction of the House for Bloodletting poses

problems of a special kind. Safety of construction, in the

presence of so many corner fireplaces, requires that its

walls be built in masonry. The house is not inhabited by

any permanent residents and serves one purpose only:

bleeding and recovering from this treatment. There is no

need for the designation of any internal boundaries between

the primary function of the building and such subsidiary

functions as sleeping or stabling animals which in the plans

of other buildings led to the delineation of aisles and leanto's;

and this is the reason, in our opinion, why the drafting

architect showed it as a unitary all-purpose space. Yet the

size of the building argues against the assumption that it

was surmounted by a roof that spanned the entire width of

the house in a single span. For the nave of a church a roof

span of 35 feet would be normal practice in this period, but

in a simple service structure it would be an anomaly. We

have introduced in our reconstruction of the House for

Bloodletting two inner ranges of roof-supporting posts

whose presence cannot be proven from the simple analysis

of the plan of this building.[413]

SITE PLAN

Antiqiuores consuetudines Cluniacensis monasterii, collectore Udalrico

Monacho Benedictino, Book. 11, chap. 21, ed. Migne, Patr. Lat., CXLIX

1882, cols. 709-10.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||