V.18.4

SUPERIOR STANDARDS OF SANITATION:

COLLECTIVE PLANNING AND

CHRISTIAN RETICENCE

THE MONASTERY: A PLANNED SOCIETY

The basic ecological reason for these comparatively high

standards of monastic sanitation are easy to define: in

contrast to the medieval or classical city, whose growth was

subject to pressures beyond the control of its inhabitants,

the monastery was a planned society. Its population was

stable, and in general not subject to unexpected fluctuations.[669]

The same care that was used in regulating the

spiritual life of the community, therefore, could also be

applied to the organization of its physical environment.

DIFFERENCE IN

UNDERLYING PHILOSOPHICAL CONCEPTS

There are other reasons, moreover, of a deeper and more

philosophical nature that made it necessary for this side

of life to be carefully ordered. The classical civilizations

of Greece and Rome, affirmative in their response to the

human organism and the pleasures derived from it, reacted

to the problem of evacuation of human waste with the

same naturalness with which they responded to the phenomenon

of eating or breathing. To the Christian mind,

taught to "chastise the body" and to "deny the desires of

the flesh,"[670]

it was, by contrast, an indignity inflicted upon

man because his soul was condemned to reside in a body.

This different concept is as manifest in the terminology

used to define this physiological inevitability as it is in the

layout of the building devised for its accommodation. The

classical languages are clear, descriptive, and to the point

on this matter.[671]

The monastic language, as one is not

surprised to find, is reticent but not prudish. St. Benedict

coined the evasive phrase ad necessaria naturae exire ("to

go out for the necessities of nature")[672]

which becomes the

base for numerous insignificant variations subsequently

used, such as necessitas fratrum,[673]

corporis necessaria,[674]

corporea

necessitas naturae,[675]

necessitas naturae;[676]

or the variants

necessarium, exitus necessarius, or requisitum naturae used on

the Plan of St. Gall—a terminology designed to express the

inescapable condition of the function it denotes.

The needs to which he attends in the privy were not

only the lowest of all activities in which a monk was bound

to engage, but were also a source of mortal danger. The

light shown on the Plan of St. Gall as an obligatory piece of

equipment in the Monks' Privy is a precautionary measure

aimed at more than merely protecting the monks from

stumbling in a physical sense.[677]

Besides his bed and his

bath, this was the only other place where, by no fault of his

own, he could not avoid bodily contact with himself. Like

the temptations of the dormitory and of the bathhouse, the

temptations of the privy could only be met with the most

stringent of directives for conditions and time of use—

especially strict in the case of the younger monks. We learn

more about these from Carolingian commentaries to the

Rule of St. Benedict than from the Rule itself.

[678]

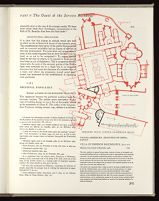

ARCHITECTURAL IMPLICATIONS

It is clear that this change in attitude would also have

its effect on the architectural layout of the monastic privy.

The amphitheater-style layout of the public Roman latrine

with its convivial sociability had no chance of survival in

this new environment. The prescribed and proper deportment

of the monk required that he draw his cowl over his

head, so as not to be recognized.[679]

To expose himself

freely to the view of others, or be exposed to theirs, would

have been an act of blasphemy. This is unquestionably the

reason why the seats of the monastic privies of the Middle

Ages were stretched out in a single line in an elongated

structure that had more the character of a corridor than of

a room, and where any propensity toward social intercourse

was frustrated by the establishment of separating

cross partitions.