The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. | V.17.7 |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.17.7

HOUSE FOR SWINE AND SWINEHERDS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Iste sues locus enutrit custodit ad/& ultas[644]

This place nourishes the [young] pigs [and]

guards the mature sows

The House for Swine and Swineherds (fig. 491) lies west of

the House for the Goats and north of the House for Foaling

Mares. Its center room, which has a fireplace, is designated

"the hall of the swineherds" (domus porcariorum). The east

aisle contains a vestibule and the "bedrooms of the herdsmen"

(cubil pastorum). The west aisle and the lean-to's are

not designated. There can be no doubt, however, about their

function. In all the other houses, this area was reserved for

the animals.

A FARROWING PEN

The House for Swine and Swineherds, as its explanatory

title states, was primarily a farrowing pen. It was the place

where the sows were kept during the winter—those sows,

that is, who would produce the litters to make up the

subsequent year's herds. All other pigs were slaughtered

in December.[645]

The number of pigs that could be housed

together is determined by available trough space. Feed

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR THE COWS AND COWHERDS

486.B EAST ELEVATION

486.A PLAN

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

In reconstructing this building we were in principle guided by the same criteria that governed reconstruction of the House of the Gardener and

his Crew (figs. 427. A-F), but because this house is the larger by over twice the area of the former structure, we decided to furnish it with a

hipped roof on the supposition that it would be needed for greater wind resistance.

As for all structures housing both men and animals on the Plan, it was necessary to lead animals to their stalls directly through the common

living area used by the herders, whose sleeping quarters in the aisles may have been divided from the stalls by little more than a partition.

486.D TRANSVERSE SECTION B-B

486.C LONGITUDINAL SECTION A-A

486.E NORTH ELEVATION

The habit and custom of housing beasts in close contact with man was of centuries' long standing in Northern Europe. Even in the sophisticated

House for Distinguished Guests (Building 11; cf. fig. 396, p. 146), 9th-century social amenities did not yet preclude the arrangement whereby

the visitors' horses were led through the common living and dining area to their stalls.

The length of the center space of the House for Cows and Cowherds is 52½, feet, suggesting that its roof supporting posts were to be spaced at

10½-foot intervals, or within the normal range for bay division in a building of this kind.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR FOALING MARES AND THEIR KEEPERS

487.

487.X

Lying in the extreme southwest corner of the site, the layout of this structure in all of its basic dispositions is identical with that of the House

for Cows and Cowherds. Virtually without question it was intended to be the same size, but, falling at a point on the tracing where the

parchment corner tapers, the draftsman of the Plan was doubtless compelled to reduce the size of the building slightly in accommodation to the

limitations of his sheet.

All the larger breeds of livestock were quartered in separate facilities lying in close proximity to one another. Outlines on the Plan indicate

that they were separated by fences or other partitions from one another. During the winter, animals would be confined to their stalls; in spring

they could be taken to pasture through secondary exits in the peripheral wall enclosure (which are not shown on the Plan).

Horses and oxen kept in these facilities would be used as draft animals, the former perhaps for riding; the cattle for breeding and milking; the

mares exclusively for breeding. As regards the inclusion of a stud in a monastic community, the relationship of monastic with crown services and

economics is discussed in Volume I, Chapter IV, "The Monastic Polity."

488. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). PSALM LXXII (73)

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 41v (detail)

[Courtesy of the Utrecht University Library]

This detail is one of the most interesting examples of the method used by the illuminator of the original Late Antique manuscript (after which

the Utrecht Psalter was modeled) to convey general concepts in imagery taken from man's daily life. Verse 22 of the psalm, "So foolish was I

and ignorant; I was as a beast before thee", serves to embody the concept "beast" in the touching representation of a mare suckling her foal. In

this manner the illuminator transmitted to the Middle Ages a composition borrowed from one of the best periods of Roman painting. It has a

striking counterpart in a painting from Herculaneum (now in Naples, Museo Nazionale) showing a doe suckling Telephos (see L. Curtius, Die

Wandmalerei Pompejis, Leipzig, 1929 8, fig. 5).

and boars, 18 inches. The required sleeping and feeding

area is 6 square feet per pig. The minimum farrowing pen

is 5 feet square. There should also be a dung passage 3 to 4

feet wide.[646] If the area available for pigs in the House for

Swine and Swineherds on the Plan were to be divided into

farrowing pens 5 feet square, it would accommodate twenty-one

sows with litters (five under each lean-to; eleven in the

aisle). If the housing capacity were to be calculated on the

basis of the available square footage, without allowing

extra space for litters, the number of pigs could easily be

doubled.

MEAT FOR THE SERFS, AND FOR THE YOUNG

AND SICK MONKS

In the Middle Ages swine and sheep were the chief

animals raised for meat. Many monasteries maintained

large herds of both, often under the supervision of the

monks themselves. Swine and sheep were also favorite

items of tithing. In the deeds of the monastery of St. Gall,

published by Hermann Wartmann, sucklings, yearlings,

and fully fattened sows are often part of the regular deliveries

from villagers and other tenants. In calculating these

tithes, a distinction was made between the heavy winter

swine, which had been fattened on acorns and beechnuts

while out to pasture in the forest, and the leaner and

less desirable summer swine. In years when the weather

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR GOATS AND GOATHERDS

489.

489.X SITE PLAN

The House for Goat and Goatherds (36) lies next to that for cattle and cowherds (37) and in the same row of buildings. Its layout is identical

with that of the House for Sheep and Shepherds (35) north of it, that for swine and their herdsmen (39) west of it, and the House for Servants

from Outlying Estates (38), whose reconstruction (below, p. 157, fig. 403. A-D) is applicable to all of these installations of the Plan.

These structures are straightforward examples of what in our previous discussion we have referred to as the "standard house" of the Plan of St.

Gall (i.e., Variant 4; see above, p. 85, fig. 334). Ranged side by side in two rows, with a sense of symmetry that clearly had a classical touch,

they appear to us almost as a village arranged by the ordering mind of an urban planner. For earlier and later examples of non-monastic

clusters of this type, see figures 259, 335, and 336.

490. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). PSALM XXII (23)

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 45r (detail)

[Courtesy of Utrecht University Library]

The five goats grazing on a hillside are part of a larger scene; it includes a herd of cattle and flock of sheep by the banks of a stream, to

illustrate verses 1 and 2 of the psalm: "The Lord is my shepherd . . . . "

The pen-and-ink depiction of these goats, two of which rise on their hind legs reaching as high as they can to crop the choice leaves, and

snapping at each other in their greed, is a display of posture and behavior so distinctively of goats that it places this scene among the outstanding

pictorial accomplishments of the Carolingian Renascence—a stunning revival in the scriptorium of Reims (816-835) of a type of pictorial

illusionism that even in Late Antiquity was practised only by artists of the greatest skill and accomplishment.

kind; in years when the growth was lean, the monks preferred

the corresponding value in currency or in sheep

(quando esca est porcum solido valentem I, et quando esca

non est arietum bonum).[647] A vital prerequisite for the raising

of herds of swine by the monastery itself was the possession

of forests, which might be placed under the care of "monastic

foresters" (forestarii). A guarded copse of wood, reserved

for the specific purpose of fattening swine (quaedam silvula

ob porcorum pastum custodiebatur), is mentioned in the

Life of St. Gall and was apparently the scene of a number

of miracles, all of which perhaps tends to stress the idea

that this branch of the monastery's agricultural economy

held no insignificant place.[648]

Although the meat from quadrupeds was a staple in the

diet of the monastery's serfs and workmen, for the monks

themselves it was allowed only in their early childhood and

in times of illness.[649]

This rule appears to have been violated

with such frequency, however, that the monastery of St.

Gall itself, toward the end of the tenth century, drew upon

itself the anger and criticism of Abbot Ruodman (972-986)

of the neighboring monastery of Reichenau. Ruodman's

critical testimony before the Emperor Otto II resulted in a

number of imperial investigations into the conditions at

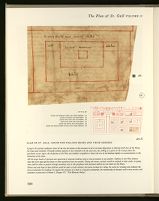

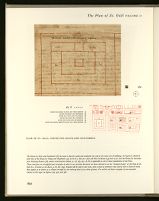

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR SWINE AND SWINEHERDS

491.

491.X SITE PLAN

In medieval illustrated calendars, the slaughtering of swine at the onset of winter, when pasture in the nearby woods became impossible, was a

favorite subject for portrayal for the month of December. In a monastic community, only those sows and boars were wintered that would

produce the litter of animals to be raised in the subsequent year. Carcasses of the slaughtered pigs were intended to be hung in the Monks'

Larder; for a realistic description of how this was done, see I, 305-307, and Adalhard's directives in the Customs of Corbie, in the chapter

devoted to swine (translated, III, 118f.)

492. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). PSALM LXXIX (80)

UTRECHT, UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 47r (detail)

[Courtesy of the Utrecht University Library]

The picture, drawn in the most delicate scatter of lines, depicts the powerful bulk of a large boar devouring the boughs of a spiraling vine. It is

an illustration to the lament of the Psalmist over his people having fallen in God's disfavor: "Thou hast brought a vine out of Egypt: thou

hast cast out the heathen and planted it" (verse 8); "The hills were covered with the shadow of it, and the boughs thereof were like the goodly

cedars" (verse 10); "Why hast thou then broken down her hedges so that all they which pass by the way do pluck her? The boar out of the

wood doth waste it, and the wild beast of the field doth devour it" (verses 12-13).

the opportunity to describe these investigations with

color and tendentious distortion.[650]

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||