The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. | V.17.4 |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.17.4

HOUSE FOR COWS AND COWHERDS

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Hic arm[enta] tibi laċ fa & us lac atq· ministrant[626]

Here the cows furnish you with milk and offspring

Directly west of the House for Horses and Oxen, within

the fences of a large rectangular yard containing four other

livestock buildings, is the House for the Cows and Cowherds

(fig. 483). Its title makes it irrevocably clear that the

animals that find shelter in this structure perform the dual

role of serving as dairy and breeding stock. The house is

entered broadside by a door leading directly into the "hall

of the herdsmen" (domus armentariorum), which is provided

with the customary central fireplace. Ranged on three sides

around this space, in the shape of the letter U, are the stables

for the dairy cows (stabula); the extremities of this stable

479. CHEDDAR, SOMERSET, ENGLAND. LONG HALL OF THE SAXON PALACE. 9TH CENTURY

[after Rahtz, 1962-63, 58, fig. 20]

The house, slightly boat-shaped (most markedly so on the west side) was 78 feet long externally, and 20 feet wide across the middle. Its walls

consisted of closely spaced posts, 9 inches square, set against the outer edge of a continuous trench, and in certain places doubled by a row of

inner posts of lighter scantling sloping inward. The entrances were in the middle of the long walls, with a minor one toward the north end of the

east side. A spread of burnt clay in the southern half of the house close to the center may indicate the location of the hearth.

"bedrooms for the servants" (cubilia seruantiū).

Both Keller and Willis[627]

interpreted the area designated

as domus armentariorum as an "open court" and the square

in its center as "a small house perhaps inhabited by the

overseer." There would be no need to refer to this superannuated

interpretation had it not been rescuscitated lately

in Alan Sorrell's recently published reconstruction of the

sufficiently stressed in earlier parts of this study, can only

have referred to a covered portion of ground. It is the

author's favorite term for "hall" or "living room" and

cannot under any circumstances be interpreted as "courtyard."

The square in the center, which is common to all

the guest and service buildings on the Plan, is clearly

identified in some of them as "fireplace" and in others as

"louver."[629]

The House for the Cows and Cowherds is 87½ feet long

and 50 feet wide, but whether this is the length of the

original scheme is somewhat doubtful, since in this corner

of the Plan the parchment contracts, and it is possible that

the copyist found himself compelled to reduce the length

of the building in order to adjust to this condition.

The central hall of the cowherds measures 22½ feet by

52½ feet; its aisle and lean-to's have a width of 17½ feet.

The traditional way of housing a dairy herd was to tie the

cows in pairs in stalls 5 feet long and 7 feet wide.[630]

The

aisle and lean-to's of the House for the Cows and Cowherds

are wide enough for the animals to be tied up in two rows,

one facing the outer walls (their customary protohistoric

position) and another one facing the inner wall partitions.

If stalled in this manner, the House for the Cows could

have accommodated a total of seventy cows. If they were

tied in a single row against the outer walls only, this figure

would have to be reduced to forty.

480. PILTON, SOMERSET, ENGLAND. BARN OF GLASTONBURY GRANGE. 15TH CENTURY

[Photo: Quentin Lloyd]

Long barns with one or several transeptal porches are very common in the Midlands and southwest of England. They are rarely less than 100

feet long, often come close to 200 feet; and one example, the barn of the Benedictine abbey grange of Abbotsbury, Dorset, attained the astonishing

length of 267 feet. The building type has never been systematically studied. For individual examples see Andrews, 1900, passim; Horn and

Charles, 1966, Horn and Born, 1969, and Charles and Horn, 1973. F. W. B. Charles and Jane Charles recently measured this barn for us. It

is 108 feet 6 inches long, 44 feet wide, and 17 feet high from floor to wall head.

The inscription is damaged. Hic armenta tibi [lac] faetus lac atque

ministrant is the traditional reading. After the title was written, lac was

shifted forward from its position between faetus and atque to a place

between tibi and faetus; but the scribe failed to erase or strike out the

superfluous lac.

MILK AND CHEESE:

PRIMARY ITEMS IN THE MONKS' DIET

The primary purpose of this herd of dairy cows was to

provide milk and cheese for the table of the monks. Butter

does not seem to have been an important item in the monastic

diet. The records of the monastery of St. Gall list altogether

not more than one pint of butter.[631]

From the same

records we learn that in the territory of St. Gall cheese

came in two sizes: a large round cheese (caseus alpinus) of

the same diameter, more or less, as a Swiss cheese of

today, usually cut into four parts (qui secantur in IV partes),

occasionally into six or eight; and a "hand cheese," which

was cut into two parts only (qui secantur in duas partes).

Cheese was one of the most common articles of tithing

contributed by the outlying farms, especially those in the

mountains which specialized in cattle raising; and the

annual revenue at St. Gall from its possessions in the

territory of Appenzell alone was over 2,000 cheeses.[632]

MEDIEVAL PARALLELS

The external appearance of the House for the Cows and

Cowherds must have been very similar to that of the

Gardener's House (figs. 426-427), except that it was considerably

larger, as one would expect it to be in view of its

different function. It is the standard house of the Plan,

minus one aisle on one of its long sides, which makes the

main room of the house directly accessible from the exterior,

a distinct advantage in buildings where great numbers

of the larger breeds of animals, and especially horned

cattle, are sheltered, because this arrangement reduces the

number of doors through which the cattle must be taken as

they enter and leave their stalls (figs. 483, 486). This house

type must have been very common in the Middle Ages. The

earliest literary evidence for its existence, so far as I can

judge, occurs in a dossier of twelfth-century lease agreements

that record the manorial holdings of the Dean and

Chapter of St. Paul's in London.[633]

On a manor located in

481. TISBURY, WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND. PLAN, GRANGE BARN. 15TH CENTURY

[Redrawn after Dufty, 1947, 168, fig. 2]

The barn at Place Farm was part of a grange once owned by the abbesses of Shaftsbury. Its external dimensions are 196 feet long by 38 feet

wide. It is lengthwise divided into 13 bays by roof trusses with arch-braced collar beams meticulously aligned with the buttresses of the masonry

walls. Two transeptal porches in the middle of the barn are original. The masonry of the jambs of the other four entrances is modern; these

openings were probably not part of the original structure. The roof is thatched.

these lease agreements is described as follows:

Juxta hoc orreum est aliud, quod habet in longitudine xxx. ped. et dim.

preter culacia: et unum calacium est longitudine x. ped. et. dim.

Alterum viii. ped. Tota longitudo hujus orrei cum culatiis xlviii. ped.

Altitudo sub trabe xi. ped. et dim. et desuper usque ad festum ix. ped.,

latitudo xx. ped.; nec habet preter i. alam, quae habet in latitudine v.

ped. et in altitudine totidem. Hoc orreum debet Ailwinus reddere plenum

de mancorno preter medietatem quae est contra ostium, quae debet

esse vacua, et haec pars est latitudinis xi. ped. et dim.[634]

Adjacent to this barn there is another one, the length of which is

30½ feet, not counting the lean-to's. One of the lean-to's is 10½ feet

deep, the other 8 feet. The total length of the barn, lean-to's included,

is 48 feet. The height below the tie beam is 11½ feet, and

above, between the tie beam and the ridge, 9 feet. The width [of

the nave] is 20 feet. And it has only one aisle, which is 5 feet wide

and equally high. This barn Ailwinus must render full of mancorno

with the exception of the center bay which lies opposite the entrance

and must be left empty, and this part is 11½ feet deep.

The barn of Wickham is just a little over half as large as

the House for the Cows and Cowherds on the Plan of

St. Gall, but its layout is identical. It is noteworthy that

the twelfth-century writer in describing this barn makes a

clear distinction between the aisle (ala) which is attached

to one of the two long sides of the barn and the two leanto's

(culatium) which are attached to the narrow ends of the

building. In English this distinction is not always maintained.

Culatium (from culus = pars cujusvis rei posterior[635]

)

is a highly descriptive term for that section of the barn which

lies under the hipped part of the roof at the short end of

the building. The writer also makes a clear distinction

between the principal space of the barn, which he refers to

simply as "barn" (orreum), and all the peripheral spaces.

The dimensions listed for all the constituent parts of the

building make it clear that the center space was higher

than the surrounding spaces and that it had a double-pitched

roof (fig. 485A-D). This is strong evidence for

the correctness of our reconstruction of the House for the

Cows and Cowherds (fig. 486A-E) and all the other buildings

on the Plan which are laid out in a similar manner.

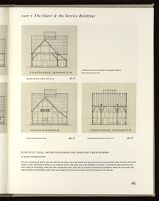

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES, OXEN, AND THEIR KEEPERS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION [1:192]

482.B

482.A LONGITUDINAL SECTION

PLAN

The only difference between the medieval long houses with transeptal porches shown in figs. 477-481 and the House for Horses and Oxen (fig.

474) is that the latter is furnished with aisles serving as quarters for the oxherds and horse grooms. Traditionally this building type is single-spaced

and in this form either used as a dwelling, or for the storage of harvest. Aisles were incorporated in the House for Horses and Oxen

because it was intended to accommodate both men and beasts.

The total length of this building on the Plan is 145 feet; the living space measures 35 by 37½ feet and the stables each are 52½ feet long,

suggesting that the roof-supporting trusses were placed at 11½ foot intervals.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

482.D WEST ELEVATION

482.C EAST ELEVATION

SCALE 1/16 INCH EQUALS ONE FOOT [1:192] FOR GRAPHIC SCALE SEE PRECEDING PAGE

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Our reconstruction of this house as a transeptal space the ridge of which intersects the main ridge at right angles and at the same height, is

made in consideration of the fact that the transept extends across the entire width of the structure, bisecting the aisles in which the herdsmen

were to sleep. We are also visually emphasizing the great importance of this transept which may have been intended to serve as dining area for

all of the monastery's herdsmen (cf. above, p. 278).

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN AND THEIR KEEPERS

NORTH ELEVATION is similar but of opposite hand to

the SOUTH ELEVATION

482.F TRANSVERSE SECTION B-B

482.E SOUTH ELEVATION

482.G TRANSVERSE SECTION C-C

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

We saw no functional need to raise the roof over the aisles, where the oxherds and horse grooms were to be quartered, above tie-beam level of the

stables. In this same manner bedrooms are treated in all the other guest and service buildings of the Plan. To extend the main roof across the

entire width of the building would have been considerably more costly and in construction functionally superfluous—unless one can assume that

the full width of the building at floor level was needed as loft above the tie-beam level for storage of straw and hay.

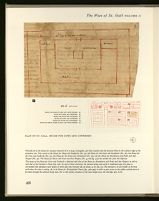

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR COWS AND COWHERDS

483.X SITE PLAN

Virtually all of the houses for monastic livestock lie in a large rectangular yard that extends from the entrance Road to the southern edge of the

monastery site. They consist of the House for Sheep and Shepherds (No. 35); the House for the Goats and Goatherds (No. 36); the House for

the Cows and Cowherds (No. 37); the House for the Swine and Swineherds (No. 39); and the House for Broodmares and Foals and their

Keepers (No. 40). The House for Horses and Oxen and their Keepers (No. 33 and fig. 474) lies outside this yard, but adjacent.

The layout of the House for Cows and Cowherds is identical with that of the House for Broodmares and Foals and their Keepers as well as

with that of the Gardener's House (fig. 426). In each of these structures, the common living room with its traditional open fire place is

surrounded with subsidiary outer spaces on three sides only (variant 3B; see above, p. 85, fig. 33). The entrance is in the middle of the long

wall where the aisle is missing. As in the House for Distinguished Guests (figs. 396-399), in order to gain access to the stables animals have to

be taken through the common living room. For a 12th century structure of the same design see p. 281 and figs. 485. A-D.

484. UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830). DEUTERONOMY, XXXII: 1-4

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CODEX 32, fol. 86r (detail)

[Courtesy of Utrecht University Library]

The illusionistic Late Antique style was practiced with superb assurance by the illuminator of the lost manuscript after which the Utrecht

Psalter was modeled. Scenes of agricultural life such as this one of a herd of cattle and a man churning butter are of a richness of perception

surpassing any other Carolingian manuscript. This intensely classical style disappeared from the medieval scene almost as rapidly as it was

adopted, giving way to more abstract concepts of painting. It took close to 500 years of gradual reconquest of reality by art for rural scenes

again to be as accurately depicted as in this unique Carolingian manuscript. The marginal scenes of the Luttrell Psalter (figs 467, 475, and

476) are among the high-water marks in this development that, at certain stages, was stimulated by availability of copies of the Utrecht

Psalter that were made in England in the 10th and 11th centuries.

The lease agreements of St. Paul's date from 1114 to

1155.[636]

Obviously, they establish only a terminus ante quam,

telling nothing about the age of the barns. Some of them

may have been of relatively recent date, others may have

been centuries old.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||