The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. | V.17.1 |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.17.1

ANIMAL HUSBANDRY:

AN INTRINSIC

PART OF THE MONASTIC ECONOMY

The presence on the Plan of St. Gall of a vast array of

houses for livestock and poultry and their keepers may at

first seem puzzling in view of the monks' essentially vegetarian

diet. It becomes a less surprising phenomenon,

however, when one considers that, although meat was categorically

interdicted to the monks themselves by a rule

that left no margin for ambiguity, it was permitted to

the serfs and workmen, who outnumbered the monks, and

even to the monks themselves in times of sickness and

during the period of bloodletting.[594]

But there are other

reasons, and probably more important ones, why the raising

of livestock was a necessary part of the monastic

economy. Animals were needed for hauling and riding.

Without horses and oxen harnessed to plows and carts,

the serfs could neither have tilled the soil nor brought in

the harvest. Saddle horses were an indispensable means of

transportation for the abbot or any other monastic official

whose business took him onto the monastery's outlying

estates. Horses had to be raised for the king as an annual

contribution to the common defense, and horses had to be

kept in readiness for the armed men whom the monastery

was required to dispatch to the king's army in times of

war.[595]

Cows, sheep, goats, and pigs were slaughtered for their

meat, and from the Liber benedictionum of Ekkehart we

learn that the cuts of meat from these animals were as

cherished in his day on the tables of those who could

afford them as they are today.[596]

But cows, goats, and sheep

also produced milk, a more important product, because it

was used to make cheese—a staple in everyone's diet.

Sheep's wool was indispensable for making coats and

blankets. Leather was made from the hides of oxen. The

skin of the calf and the lamb yielded a commodity that was

of prime importance for the monastery's religious and

educational mission: parchment. The quill used in writing

the sacred texts came from the wings of geese.

The meat of poultry, as has already been pointed out,

was not subject to the same restrictions as the meat of

quadrupeds. The second synod of Aachen (817) granted

it to the monks for a period of eight days on each of the

great religious feasts of Christmas and Easter. Later the

number of days was reduced to four on each of these

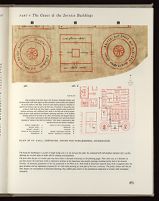

PLAN OF ST. GALL, HENHOUSE, HOUSE FOR FOWLKEEPERS, GOOSEHOUSE

466.

466.X

SITE PLAN

The proximity of the fowl runs to the Granary, Vegetable Garden, and

Orchard shows with what degree of skill convenience and necessity were planned

for by the makers of the Plan. Grain for feed could be gleaned or threshed at

need in the Granary and carried to the fowl runs. Proximity to the gardens was

a boon for both birds and their keepers—garden clippings might provide the

chickens and geese with additional food, while in the beds and orchard manure

from the pens could quickly be distributed, enhancing sanitation. In all facilities

housing animals on the Plan of St. Gall, the herdsmen and keepers lived in

close contact with beasts; while the fowlkeepers were spared the literal

necessity of "going to bed with the chickens," their house is separated by only

ten feet from the two poultry enclosures.

The house for fowlkeepers is 35 feet in length (ridge axis E to W) and 42½ feet wide. Its communal hall with fireplace measures 22½ × 35 feet,

allowing two 10-foot aisles at either side for sleeping accommodation.

The form that the pair of circular pens may have taken is discussed extensively on the following pages. Their sheer size, at a diameter of

42½ feet (across the outermost circle) is impressive evidence of the importance that poultry (perhaps including ducks) had in the monastic

economy. A monastery population of the size postulated on the Plan of St. Gall would in itself have required many birds to augment diet; the

guest facilities and lay dependents proposed for St. Gall made planning for fowl pens of this size a necessity. The poultry houses and that for

their keepers are masterpieces of functional planning; they exhibit great charm in the symmetrical composition of circular with rectangular

structures.

467. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). GOOSEHERD

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 169v (detail)

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

A goose and five goslings are threatened by a hawk; the gooseherd waves his hood and staff at it to drive it off. Geese were not only useful as

food, but kept vermin and garden pest populations down; their raucous and hostile response to strangers, well known since the early days of

Rome, may have added to their utility in the life of a large monastic complex.

prohibited, hens were of vital importance for their capacity

to produce eggs—a year round staple in the monastic diet

and one of its most important sources of protein. For egg

production alone, the raising of poultry was bound to be

one of the most important aspects of monastic animal

husbandry, and the polyptichs and household accounts from

medieval abbeys abound with records of supplementary

deliveries of eggs, chickens, and hens (ova, pulli et gallinae)

from the abbey's outlying farms.[598]

Lastly we must not overlook the fact that these animals

provided the only good fertilizer that was known to the

medieval agriculturalist and one that made a vital contribution

to the enrichment of the community's crop and

harvest.

It becomes quite clear then, that despite the monks'

essentially vegetarian diet, the monastery as a self-sustaining

economic and agricultural entity could not forego

the need to raise livestock and poultry in quantities commensurate

with the number of men whom it had to clothe

and feed. In the spring, summer, and autumn the majority

of monastic animals were unquestionably put out to pasture.

For that reason, the houses for livestock and their

keepers shown on the Plan of St. Gall are likely to define

only that space which was needed to stable the animals

kept under roof and shelter during the harsh winter months

in order to insure the propagation of the species. The

costliness of stall feeding demanded that this be done with

discretion. A thirteenth-century directive recorded in the

cartulary of Gloucester Abbey rules that "no useless and

unfertile animals are to be wintered on hay and forage"

(quod nulla animalia inutilia et infructuosa hyementur ad

consumptionem foeni vel foragii) and the text makes it clear

that exceptions to this ruling should be made only with

regard to such useful and deserving animals as the plow

oxen and breeding cows (talia scilicet de quibus non credatur

posse nutriri aliquis bos utilis ad carucas vel vacca competens

ad armentum).[599]

The directive reflects a general condition

of medieval animal husbandry that pervaded all social

strata and the whole of medieval life, with only minor

variations on the highest levels.

The importance of animal husbandry is eloquently

attested by St. Fructuosus in the ninth chapter of his

Galician Rule. As noted in the translation by Barlow, this

chapter does not appear in the Fructuosan Rule for other

areas, presumably because (as Fructuosus acknowledges)

468. MEINDERT HOBBEMA

A FARM IN THE SUNLIGHT (1660-1670)

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON D.C.

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the National Gallery of Art]

any other land" and the monk in whose charge lay the

pasturing of livestock needed not only firm direction but

also moral support:

"Those who accept the charge of attending the livestock of the

monastery should show such concern for them that they will not

cause any harm to the crops, and they should be watched so carefully

and so astutely that they will not be devoured by wild beasts,

and they should be kept away from steep and rocky mountains and

inaccessible valleys, so that they will not slip over a precipice. But,

if any of the above-mentioned negligent deeds happens because of

inattention or lack of care on the part of the shepherds, they shall

straightway throw themselves at the feet of their elders and, as

though deploring great sins, shall for a considerable time suffer

penance worthy of such a fault. . . . The flocks are to be placed in

the charge of a monk who is well-proved, who was trained to this

sort of work while in the world, and who desires to guard the flocks

with such good intention that never the slightest complaint comes

from his lips. They may have younger ones assigned them by turns

to share their labor. They may have sufficient clothing and covering

for the feet. One monk, such as we have mentioned, shall be responsible

for this service, so as not to inconvenience all the monks

in the monastery. But since some who guard the flocks are accustomed

to complain and think they have no reward for such

service when they cannot be seen praying and working in the

congregation, let them harken to the words of the Rules of the

Fathers . . . recognizing the examples of the Fathers of old, for the

patriarchs tended flocks, and Peter performed the duties of a

fisherman, and Joseph the Just, to whom the Virgin Mary was

espoused, was a carpenter. Accordingly, they have no reason to

dislike the sheep which have been assigned to them, for they shall

reap not one but many rewards. Their young shall be refreshed,

their old shall be warmed, their captives redeemed, their guests and

strangers entertained. Besides, most monasteries would scarcely

have enough food for three months, if there existed only the daily

bread in this province, which requires more work on the soil than

any other land. Therefore, one who is assigned this task should

happily obey and should most firmly believe that his obedience

frees him from all danger and prepares him for a great reward

before God, just as the disobedient one suffers the loss of his

soul."[600]

The total area set aside for animal husbandry on the

Plan of St. Gall takes up more than one-fourth of the

monastery site. It accommodates six houses for the larger

breeds and two enclosures for poultry, as well as the living

rooms and bedrooms needed for their keepers. The stables

for the larger animals are concentrated in a large service

yard lying to the south and west of the claustrum; the

houses for the poultry are in the southeast corner of the

monastery site, between the vegetable garden and the

granary.

On St. Benedict concerning the consumption of meat, see above,

I, 277ff. This may be unequivocally inferred from the Administrative

Directives of Adalhard of Corbie, which regulate the distribution of meat

both to the serfs and to the guests of the monastery. See I, 305-306.

With regard to the relaxation of the general rules concerning meat

consumption during sickness and the time of bloodletting, see I, 275;

and above, p. 188.

Historia et Cartularium Monasterii S. Petri Gloucestriae, in Rerum

Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores, XXX:3, London, 1867, 215.

Cf. Hilton, 1966, 120-21.

St. Fructuosus, General Rule for Monasteries, Chapter 9, translated

by Claude W. Barlow in Iberian Fathers, vol. 2, 189-90, Washington,

D.C., 1969 (The Fathers of the Church, vol. 63). For the Latin text

see Sancti Fructuosi Bracarensis episcopi regula monastica communis, cap. IX,

in J. P. Migne, Patr. Lat. LXXXVII, Paris, 1863, cols. 1117-18. The

Common Rule of St. Fructuosus was written about A.D. 660 after he had

founded numerous monasteries in western Spain.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||