The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

THE BAKERY

The term PISTRINUM

A small vestibule left between the two bedrooms of the

servants gives access to the "brothers' bakery" (pistrinū

fr̄m̄). It occupies the eastern half of the house and its center

space forms an area 22½ feet wide and 32½ feet long.

It should be mentioned in this context that the term

pistrinum is used exclusively as a designation for "bakery"

on the Plan of St. Gall, and never in the sense of "mill,"

its original classical meaning.[555]

The equipment with which

the spaces that carry this designation on the Plan are

furnished offers the proof (figs. 462-464). Hildemar, who

touches on the matter of bake houses in his commentary

of chapter 66 of the Rule, makes some interesting etymological

comments about this term: "Pistrinum," he says,

"is the equivalent of pilistrinum, because in the early days

people used to crush grain with the aid of a pestle (pilo)

for which reason the ancients did not call them grinders

(molitores) but crushers (pistores), i.e., people engaged in

the crushing of grain (pinsores) for there were no mill stones

(molae) in use at that time, but grain was crushed with

pestles."[556]

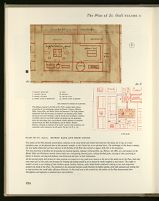

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE

462.X

THE SYMBIOTIC SCHEME IN PLANNING

The efficiency internal to the Plan of St. Gall is nowhere better demonstrated

than in the relationships among the Brewers' Granary, Mortars,

Mills, Drying Kiln, and Monks' Bake and Brewhouse. The traffic patterns

demonstrate with what economy of movement raw material, grain—bulky

and heavy even after threshing—could be moved from the Brewers' Granary

to facilities where it was further refined, and finally into the Brewhouse

where the end product, beer, was produced. Similar efficiency of movement

existed between the Mill, the Bakehouse, and the Monks' Kitchen.

However, planning for isolation of the monks' sanctum takes precedence over

convenience where monastery met the world. See fig. 463.X, p. 256.

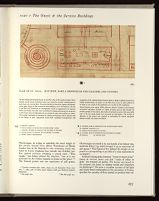

SITE PLAN

The makers of the Plan devoted extraordinary attention to the visual detail and verbal instruction for this house, for it lay, in a most

immediate sense, at the physical heart of the monastic complex, as the Church lay at its spiritual heart. The technology of this house is among

the most highly elaborated and least abstract of all facilities of the Plan that existed to support daily life in the monastery.

The close proximity of facilities for processing raw material (grain), refining it (Drying Kiln, 29; Mortar; 28; Mill, 27), and using it in the

Monks' Bake and Brewhouse assumes intense daily use—transporting sheaved grain, sacking threshed grain, carrying it after processing to

bakery or brewery, carrying end products, new bread and new beer, to their destinations.

All the starting points and termini for these processes are found in a very small area relative to the size of the whole site of the Plan. Each day

some major part of the cycles and processes for brewing and baking would be set in motion by monks assigned to such chores. The traffic in

numbers of men, to say nothing of their burdens—grain, buckets, barrows, sacks, baked bread—achieved a density of use and compaction

nowhere else found in the Plan. The planning of the associated facilities would therefore be highly specific, with little assumed and nothing left

to improvisation that would affect efficiency adversely. In this small area of the overall site, the makers of the Plan demonstrated their

thoroughness and ingenuity as administrators and architects.

The term is fascinating, since its shifting values reflect

the entire history of grain preparation from the mortar-and-pestle

stage to the milling stage, and thence by an associative

leap (because bread was often baked near the mill)

from the building in which grain was ground into flour to

the facility where bread was baked.

"Pistrinum quasi pilistrinum, quia pilo antea tundebant granum; unde

et apud veteres non molitores sed pistores dicti sunt; quasi pinsores a pinsendis

granis frumenti; molae enim usus nondum erat, sed granum pilo pinsebant,"

(Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 607-608).

Layout and equipment

The principal piece of equipment in the Bake House is

the large oven (caminus) which is installed in the southern

aisle of the house directly opposite the entrance. The oven

has a diameter of 10 feet, and is serviced from the main

room of the bakery. This room is furnished with a continuous

course of tables or shelves running in a U-formation

around three of its four walls. The total linear length of

this shelf is 62½ feet. Its depth is 2½ feet. Thus it provides

an ample general work space that could have been used

variously for any number of purposes in the course of

breadmaking.

Next to the oven and in the same aisle with it there is

a trough (alueolus) 12½ feet long and 2½ feet wide. The

space under the lean-to at the east end of the house serves

as a "storage bin for flour" (repositio farinae); this area is

7½ feet wide and 30 feet long. The Plan shows no doors

giving access either to the flour bin or to the room with the

kneading trough—one of the few genuine oversights on

the Plan.[557]

In the axis of the center space, and almost equidistant

from their edges to the shelves that line the room on three

sides, are two rectangles that together form an area 6¼ feet

wide and 10 feet long. A similar but smaller object is found

in the corresponding space in the bakery of the House for

Distinguished Guests. In the bakery of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers, however, this space is occupied by

the kitchen stove[558]

that seemingly displaces to the brew

house an oblong surface that probably corresponds to the

same pieces found in the center of the bakeries of the other

two houses. Unfortunately the Plan does not provide any

explanatory titles that would enable us to identify the

nature, construction, or function of the objects designated

by these rectangles. This is somewhat surprising because

similar objects situated in the outer aisles are clearly identified

with titles that not only explain their shape or form

(alueolus, trough) but also their function (locus conspergendi,

the place where the dough is mixed; and ineruendae

pastae locus, the place where flour is mingled [with water].)

There is no doubt that the large rectangles in the side

aisles of the bake house were the troughs in which the

dough was first mixed. Good baking practice would require

that the yeast sponge be added to the dough at this beginning

stage, and it is quite possible that after being vigorously

mixed, it was likewise here that the dough was allowed to

enter its first stage of rising. The warmth of the enclosure

near the oven, already fired by a considerable heat, would

significantly aid the rising process in the large mass of

dough.

To convert the bulk of dough into a multitude of loaves

required a different setting: large surfaces sprinkled with

flour where the mass could be broken up, kneaded, divided

and weighed into uniform batches, and shaped into loaves.

All these purposes could have been served by the large

rectangular surfaces in the center of the bakery, or, if these

rectangles were actually troughs, the work could have been

done on the shelves that lined the central space on three

sides. After the loaves were shaped and before they were

placed in the oven for baking, they probably went through

a second stage of rising.[559]

The reconstruction of the equipment used in baking

poses no problem. We have already discussed the oven

together with other heating units shown on the Plan.[560]

Their form was established early and until very recent times

did not undergo any significant changes. The same can

also probably be said about bakers' troughs, a good medieval

example of which is shown in figure 388.

I am inclined to believe that in medieval ovens, the

firing and baking chamber were one and the same unit—as

they were still in the earlier decades of this century in the

bakeries of the German village where I spent my childhood.

There the ovens were heated by wood, as was done

in the Middle Ages. When the right temperature was

reached, the coals were raked out to make room for the

loaves, and the bread was baked as the oven temperature

entered its descending cycle.

While it may not be possible to reconstruct exactly the techniques

the monks used in baking, their methods can have varied but slightly

from those still in use today. For instance, bread baked in small batches

is commonly kneaded after the dough is mixed, but a vigorous mixing

can replace that initial kneading. It is not even necessary that vigorously

mixed dough rise twice, although allowing it to do so assures a finertextured

bread. Any basic variations in the monks' baking methods

probably arose from considerations due to the quantity of bread they

made, rather than from any special mysteries inherent in breadmaking.

The daily allowance of bread

The daily ration of bread allowed to each monk was

fixed by St. Benedict:

Let a weighed pound of bread suffice for the day, whether there be

one meal only, or both dinner and supper. . . . But if their work

chance to be heavier, the abbot shall have the choice and power,

should it be expedient, to increase this allowance.[561]

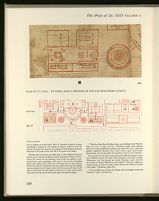

464. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

463.X SITE PLAN

463. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

Of three baking and brewing houses on the Plan, that of the monks is largest; but it

includes, besides purely functional space, two rooms for servants' sleeping quarters

and a lean-to for storing flour. Servants attached to houses for pilgrims and distinguished

guests lodged in their respective main buildings, not in the bakeries. The size

of the Bake and Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests is augmented by its separate

larder and kitchen; but when areas used solely for baking and brewing are compared,

it will be seen that the differences in size among the three like facilities are minor.

The essential replication of facilities for baking and brewing, both in function and

in the layout of each, apparently marks both traditional juxtapositions and

recognition of the combined bakery-brewery plan to adapt to efficient service for a

widely varying number of people—on the Plan from as few as twelve pilgrims to

as many as 300 monks if the population ever reached its full complement.

Routes between grain supply (Mills, Mortars, Brewers' Granary) and breweries

of pilgrims' and guests' facilities are highly circuitous and lie right through the

western paradise of the Church. But traffic of burdened servants in this most public

area of the site would hardly have presented an interruption. The sacrifice in

efficiency in this pattern was regained in maintaining the desired segregation

between worldly and claustral activities.

e. PORTER'S LODGING

f. PORCH ACCESS TO HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

i. LODGING, MASTER OF HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

h. PORCH ACCESS TO HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

9. MONKS' BAKE & BREWHOUSE

10. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

30. BREWERS' GRANARY, ETC.

31. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

32. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

28. MORTAR

29. DRYING KILN

Charlemagne, in trying to establish the exact weight of

this pound, learned from Abbot Theodomar of Monte

Cassino that in St. Benedict's own monastery bread was

baked in loaves weighing four pounds and divisible into

four quarter sections, weighing a pound each: "This

weight," the Abbot assures the emperor, "just as it was

instituted by the Father himself, is found at this place."[562]

The Roman pound was the equivalent of 326 grams.

Charlemagne increased it by one fourth of its former size,

sometime before 779, which brought it up an equivalent of

406 grams.[563]

The Synod of 817 defined the weight of one

pound as corresponding to 30 solidi of a value equivalent to

12 denarii.[564]

Adalhard distinguishes between "bread of mixed grain"

(panos de mixtura factos) and that "made of wheat or

spelt" (de frumento uel spelta). The former was issued to

the paupers; the latter, to visiting vassals and clergymen

on pilgrimage.[565]

He gives a complete account of the daily

and yearly bread consumption in the monastery of Corbie,

specifies the quantity of flour needed to produce that volume,

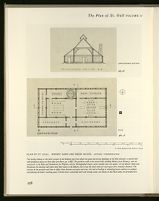

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

465.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

465.A PLAN

This facility belongs to the third variant of the building type from which the guest and service buildings of the Plan descend: a central hall

with peripheral spaces on three sides (see above, pp. 178ff). The partition wall in the central hall, dividing Bakery from Brewery, was not

structural; in the Bake and Brewhouses for Pilgrims, and for Distinguished Guests, such a divider does not appear. In the Monks' Bake and

Brewhouse the dividing wall allots more floor space to the Bakery, but in fact the work areas for each space were virtually identical. The

location of the partition wall here in effect clears between entryway and oven; the task of loading or unloading loaves could go on without

encumbering the bakers' working space. Certain doors connecting work and storage areas, not shown on the Plan itself, are provided here.

cautions the "keeper of the bread" (custos panis) to make

allowance for the yearly fluctuations in the number of

mouths to be fed by providing for a reasonable surplus of

flour in order not to be caught with a shortage, and he

admonishes him at the same time not to bake more for the

brothers than is needed, "lest what is left over should get

too hard." If this were nevertheless allowed to happen,

the old bread would have to be thrown away, and the

supply of bread replenished.[567]

"Panis libra una propensa sufficiat in die, siue una sit refectio siue

prandii et cenae. . . . Quod si labor forte factus fuerit maior, in arbitrio et

potestate abbatis erit, si expediat, aliquid augere." (Benedicti regula,

chap. 39, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 99-100; ed. McCann, 1952, 94-96; ed.

Steidle, 1952, 234-36).

The qualifying adjective propensa of panis libra una requires comment.

Delatte, 1913, 309 and McCann, 1952, 95 translate "a good pound of

weight;" Steidle, 1952, 234, more convincingly "a well weighed pound

of bread." Hildemar who is closer by eleven hundred years to the source

explains the adjective as follows: Propensa, i.e., praeponderata, i.e.,

mensurata (Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 437, commentary

to chapter 39 of the Rule). What St. Benedict wished to convey

accordingly—obviously in the interest of equity—would be that the

quantity of dough that went into the making of a loaf of bread should be

measured on the scales rather than left to the guess of the baker.

Whether this was done in the dough stage or after baking will have to

remain a moot question. At Monte Cassino, during the abbacy of Theodomar

(for source see the following note) bread was baked in four-pound

loaves, and accordingly would have to be cut into serviceable

pieces after baking. This could even have been done in the refectory

before the bread was distributed and may indeed have been the simplest

and most logical way of doing it, since even the one-pound loaves would

have to have been cut into smaller portions on the days when several

meals were served, and the bread was eaten in successive stages.

Theodomari epistula ad Karolum, chap. 4, ed. Hallinger and Wegener,

Corp. con. mon., I, 1963, 162-163; "Direximus quoque pondo quattuor

librarum, ad cuius aequalitatem ponderis panis debeat fieri, qui in quaternas

quadras singularum librarum iuxta sacrae textum regule possit diuidi.

Quod pondus, sicut ab ipso padre est institutum, in hoc est loco repertum."

I am puzzled by Semmler's interpreting this difficult passage to mean

that in Monte Cassino, the daily ration of bread, at the time of Abbot

Theodomar, was four pounds per monk (Semmler, 1958, 278). Cf.

the remark of Jacques Winandy on this subject: "Comme il apparait a

simple lecture, le pain de quatre livres devrait être divisé en quatre

parts égales." (Winandy, 1938, 281).

Synodae secundae decr. auth., chap. 22, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons.

mon., I, 1963, 478: Ut libra panis triginta solidis per duodecim denarios

ponderetur.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 2, ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I,

1963, 372, and translation III, 105.

Ekkehart, in his Benedictiones ad mensas, makes reference to a wide

variety of bread: to "cakes" (torta), "moon-shaped bread" (panem

lunatem), "salted bread" (panem cum sale mixtum), "bread leavened with

egg" (panem per oua leuatum) and "bread leavened with dredge" (panem

de fece leuatum), "bread made of `spelt' " (de spelta), "rye" (triticeum

panem), "wheat" (panem sigalinum), "barley" (ordea panis), "oat"

(panis avena), "fresh bread" and "old bread" (panis noviter cocti and

recens coctus panis), "warm bread" and "cold bread" (calidi panes and

gelidus panis), and lastly, the "morsels and crumbs" (fragmina panum)

left over from each meal. (Benedictiones ad mensas, lines 6-20. See Liber

benedictionum Ekkeharts IV, ed. Egli, 1909, 281-84 and Schulz, 1941.

A single cycle of firing and baking

If we presume that St. Benedict's allowance of a daily

pound of bread for each monk applied to the monastery's

serfs as well, the monks' bakery on the Plan of St. Gall

would have to have been capable of producing 250 to 270

pounds of bread per day.[568]

An analysis of the dimensions

of its oven and the amount of space required for this output

discloses that this volume of bread could be produced in a

single cycle of firing and baking.[569]

A passage in Ekkehart's Casus sancti Galli, which has

consistently been misconstrued, reads that the monastery

of St. Gall had an oven (clibanum) capable of baking a

thousand loaves of bread at once and a bronze kettle

(lebete eneo) and drying kiln (tarra avenis) capable of

holding one hundred bushels of oats.[570]

This is not a

statement of fact, but a passage in a speech by Abbot

Solomon III, which Ekkehart himself refers to as "boastful"

and "fraudulent."[571]

I am relying on the calculation of my friend Thomas Tedrick who

assures me that an oven 10 feet in diameter on the inside is capable of

baking 356 loaves of bread, each weighing one pound, in a single process

of baking if all available space is utilized and the loaves, after their

expansion during baking, are allowed to touch each other. After some of

the oven's space has been subtracted for wall thickness and more for a

narrow margin of space to be allowed between the loaves to prevent them

from sticking together, the dimensions of this oven turn out to have been

planned to meet exactly the daily baking requirements of the monks and

serfs of the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||