The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

TRIP-HAMMERS WITH VERTICAL PESTLES

There existed in the Middle Ages, as already mentioned,

yet another pounding mechanism making use of camming

action that cannot be overlooked in this context. It worked

with vertical pestles rather than with recumbent hammers.

Illustrations of these are found in the Mittelalterliche

Hausbuch of about 1480,[535]

in several manuscripts of

Leonardo da Vinci[536]

and in the manuscript attributed

to an anonymous Hussite engineer of around 1430 (fig.

456). Needham considers these vertical stamping mechanisms

"as characteristically European as the recumbent

tilt-hammer was Chinese."[537]

This may be true, but there

is no historical assurance whatsoever that in Europe the

invention of the former preceded the adoption of the

latter[538]

and any attempt to interpret the pilae of the Plan

of St. Gall, or the pistillos, sive malleos, vel certe pedes

ligneos of the thirteenth-century description of the water-powered

trip hammers of the Abbey of Clairvaux in the

light of this vertically operated pounding mechanism

would be straining the available historical evidence beyond

the limits of propriety. Amongst the vertical medieval

crushing devices listed by Needham, or anyone else

as far as I can see, there is not a single one with pestles

the shape of which could in any manner be compared

with that of a hammer (malleus) or a foot-shaped member

(vel certe pedes ligneos). A hammer, whether struck horizontally

or vertically, hits its object on impact, in a position

which places its longitudinal axis parallel to the surface

that receives its blow. It can accomplish this only with the

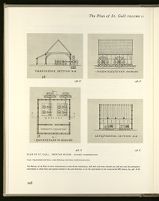

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MORTAR HOUSE. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

458.B

458.A

458.D

458.C

PLAN. TRANSVERSE SECTION, LONGITUDINAL SECTION; SOUTH ELEVATION

The Mortars of the Plan are here reconstructed as water-driven mechanisms, with their axle-trees oriented east and west and the presumptive

waterwheels to which these were geared oriented in the same direction, as are the waterwheels of the reconstructed Mill (above, fig. 448. A-E).

PLAN OF ST. GALL. AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

458.E

458.F

WEST ELEVATION, NORTH ELEVATION

If a stream existed on the site and the land gradient permitted the development of waterpower, great efficiency could be achieved by this

alignment of the wheel races. For justification of water-powered mechanisms see above, p. 232, caption to fig. 448. In actual construction, we

believe such details would have been resolved by experienced craftsmen.

its longitudinal axis. In the vertical crushing mechanism,

illustrated by the anonymous Hussite engineer (1472-78),

the Hausbuch Master (ca. 1480) and Leonardo da Vinci

(turn of the fifteenth to the sixteenth century), the pestles

are pointed, i.e., pencil-shaped, and could not by any

stretch of the imagination be interpreted as "hammer-" or

"foot-shaped" instruments. There is no doubt in my mind

that the pilae shown on the Plan of St. Gall must be interpreted

as recumbent hammers. They have the shape of

hammers, and the presence of a drum at the end, which

lies opposite the head of the hammer, as well as their

dimensions, allows for no other interpretation.[539]

For detailed references to Leonardo's drawings of vertical crushing

mechanisms see Needham, op. cit., 395, note d.

It has been generally overlooked in this discussion that the same

anonymous Hussite engineer, who furnishes us with the earliest visual

representation of a vertical pestle stamp provides us also with an illustration

of a grain-crushing mechanism, operating with recumbent

hammers (Munich, National Bibliothek, Ms. lat., fol. 17v; see Beck,

op. cit. 278-80). I am drawing attention to this fact because there seems

to be a tendency, in the literature on this subject, to think that in Europe

the use of the vertical pestle stamp preceded that of mechanisms working

with recumbent hammers, because of the erroneous view that the former

is earlier attested in the visual arts. This would not only be a conclusion

highly questionable in itself, but also one based on mistaken facts. Both

instruments portrayed and described by the Hussite Engineer are hand-operated

and of rather light construction, made for home rather than

industrial use, and therefore not really comparable to the heavy equipment

shown on the Plan of St. Gall or described in the poetic thirteenth-century

account of the waterworks of Clairvaux.

The traditional date of Ms. Lat. 197, "ca. 1430" (Beck, 1899, 280;

Needham, IV:2, 1965, 395; Horn, Journal of Medieval History I, 1975,

244) must be revised. Lynn White informs us that Bert A. Hall, in an

unpublished dissertation "The so-called `Manuscript of the Hussite Wars

Engineer' and its Techological Milieu: A Study and Edition of Codex

Latinus 197, Part 1," University of California, Los Angeles, 1971) showed

conclusively that it is two manuscripts bound together. They are from

the hands of two engineers, neither of whom can be shown to have had

any involvement in the Hussite Wars. Folios 1-28 can be dated to ca.

1472-1485, folios 29-48 to ca. 1485-1496.

It has been generally overlooked in this discussion that the same

anonymous Hussite engineer, who furnishes us with the earliest visual

representation of a vertical pestle stamp provides us also with an illustration

of a grain-crushing mechanism, operating with recumbent

hammers (Munich, National Bibliothek, Ms. lat., fol. 17v; see Beck,

op. cit. 278-80). I am drawing attention to this fact because there seems

to be a tendency, in the literature on this subject, to think that in Europe

the use of the vertical pestle stamp preceded that of mechanisms working

with recumbent hammers, because of the erroneous view that the former

is earlier attested in the visual arts. This would not only be a conclusion

highly questionable in itself, but also one based on mistaken facts. Both

instruments portrayed and described by the Hussite Engineer are hand-operated

and of rather light construction, made for home rather than

industrial use, and therefore not really comparable to the heavy equipment

shown on the Plan of St. Gall or described in the poetic thirteenth-century

account of the waterworks of Clairvaux.

The traditional date of Ms. Lat. 197, "ca. 1430" (Beck, 1899, 280;

Needham, IV:2, 1965, 395; Horn, Journal of Medieval History I, 1975,

244) must be revised. Lynn White informs us that Bert A. Hall, in an

unpublished dissertation "The so-called `Manuscript of the Hussite Wars

Engineer' and its Techological Milieu: A Study and Edition of Codex

Latinus 197, Part 1," University of California, Los Angeles, 1971) showed

conclusively that it is two manuscripts bound together. They are from

the hands of two engineers, neither of whom can be shown to have had

any involvement in the Hussite Wars. Folios 1-28 can be dated to ca.

1472-1485, folios 29-48 to ca. 1485-1496.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||