The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. | V.10.4 |

| V. 11. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.10.4

HOUSE FOR BLOODLETTING

DESCRIPTION OF HOUSE

fleotomatis hic gustandum ʈ potionariis[395]

Here is the place for bloodletting and for purging

The House for Bloodletting (fig. 416) lies west of the

Physicians' House and consists of a large rectangular space

35 feet by 45 feet. It is furnished with a central fireplace

with the customary louver and contains, besides this traditional

heating device, four additional corner fireplaces

as well, doubtless in consideration of the weakened condition

of the monks after being bled. The wall space between

these fireplaces is taken up by six benches and tables

(mensae) on which the monks were bled and purged.

The primary function of this separate house, as Leclercq

has correctly pointed out, is to relieve the Monks' Infirmary

of the many people who were to receive the incision of the

lancet as a cure for a vast variety of ailments, real and

imaginary.[396]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR BLOODLETTING

The vulnerable condition in which patients found

themselves through the process of bleeding

required that the House for Bloodletting be well

heated. This was accomplished by installation of

four corner fireplaces, in addition to the traditional

open fireplace in the center of the building. Safety

from fire hazards would require that the walls of

the House for Bloodletting be built in masonry.

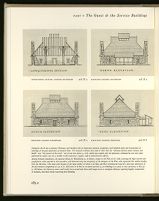

416.X.2 TRANSVERSE SECTION LOOKING EASTWARD

Without doubt Carolingian builders could have

covered a house 35 feet wide with a single span

(the nave of the Church after all had a span of 40

feet) but in most medieval buildings such a span

would have had additional support in two rows of

free-standing inner posts, if more than 25 feet

wide. For this reason in our reconstruction we have

introduced four additional inner posts carrying

roof plates, which in the longitudinal direction of

the building are slightly cantilevered to support the

rafters of the hips of the roof.

416.X.1 PLAN AT GROUND LEVEL

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

416.X.3 LONGITUDINAL SECTION, LOOKING SOUTHWARD

416.X.5 ELEVATION LOOKING NORTHWARD

416.X.4 ELEVATION LOOKING SOUTHWARD

416.X.6 ELEVATION LOOKING WESTWARD

Caring for the ill was a primary Christian, and therefore also an important monastic occupation, and included study and transmission of

teachings of the great physicians of classical times. Yet monastic tradition also made it clear that the "ultimate decision about sickness and

health" was "the concern of the Lord," not of man (see above, p. 176), which may explain why the physician, although his arts were often

performed by monks, was not a member of the monastery's regular staff of administrative officers.

Among monastic foundations, the separate House for Bloodletting is, we believe, unique to the Plan of St. Gall, attesting the high curative and

prophylactic value attached to this procedure, and demonstrating the perspicuity of the designers of the Plan, who separated this medical facility

from the infirmary. This made sense because of the large number of monks to be bled, and their convalescent state for a few days afterward. If

the full monastic complement of 130 at St. Gall were to be bled at six-week intervals (1,170 bleedings in a year) as was customary at Ely (cf.

p. 188 below), the Infirmary alone could hardly have served both those with longer-term or contagious illnesses requiring lengthy recuperation

or isolation, and those merely recovering from bleeding.

417. LUTTRELL PSALTER (1340). LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, ADD. MS 42130, FOL. 61

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

A physician bleeds a patient under the interested gaze of a large kingfisher. The iconography of this bird is ancient and complex; with its

ability to hurl itself into the water and then arise after having apparently drowned, it captured the Christian imagination to become a symbol

for the resurrected Christ. Perhaps its association with the act of bleeding symbolizes the hope of the patient for restored health.

Fleotomatus is a common medieval form for classical Latin phlebotomatus,

from Greek φλεβοτομεῑν, "to open a vein" and φλεβοτομί α,

"bloodletting." The ῑ between gustandum and potionariis was correctly

transcribed as vel by Keller, 1844, and all subsequent writers. Cf.

Battelli, 1949, 110.

MONASTIC VIEWS ON BLEEDING

The Rule of St. Benedict is silent on the subject of

bleeding,[397]

and there is no certainty as to what point in

history bleeding became a regular practice in monastic life.

A description in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of a case of

unsuccessful bloodletting causing intensive swelling and

nearly leading to the death of a nun, suggests that bleeding

was a fully adopted form of medical treatment in the

monasteries of England at the time of Theodore of Tarsus

(669-690). The same story also reveals that when something

went wrong with the operation this was likely to be

attributed not to the use of infectious tools or other forms

of medical malpractice, but to the fact that the operation

was performed at the wrong time: "You have acted

foolishly and ignorantly to bleed her on the fourth day of

the moon," Bede records Bishop Wilfrid of Hexham to

have exclaimed. "I remember how Archibishop Theodore

of blessed memory used to say that it was very dangerous

to bleed a patient when the moon is waxing and the Ocean

tide flowing. And what can I do for the girl if she is at the

point of death?"[398]

A book, De minutione sanguis, wrongly

attributed by tradition to the Venerable Bede, recommends

that the blood be let between March 25 and May 26, on the

assumption that this was the season "during which the

blood develops in the human organism" (quia tunc sanguis

augmentum habet). After this period, the operation was to be

undertaken only with a due regard for the qualities of

the seasons and phases of the moon (sed postea observandae

sunt qualitates temporum et cursus lunae).[399]

The first synod of Aachen (816) abolished the custom

according to which large segments of the community were

bled at a fixed date, and ruled that individuals be bled

according to need. It reaffirms the right of those who are

exposed to this treatment to receive a fortifying diet of food

and drink, including at least by implication the otherwise

forbidden meats (Ut certum fleutomiae tempus non obseruent,

sed unicuique secundum quod necessitas expostulat concedatur

et specialis in cibo et potu tunc consolatio prebeatur).[400]

The food for the monks who were bled was doubtlessly

prepared in the kitchen of the Infirmary, which lies directly

to the west of the House for Bloodletting. The number and

length of the tables in this house would permit the simultaneous

feeding of a maximum of thirty-two monks, if we

count 2½ feet as the normal sitting space required by each

monk, as we did in calculating the seating capacity of the

Monk's Refectory.[401]

The number of monks to be bled on

a single day could not exceed this figure; and if as many as

thirty-two were bled in a single day, this operation could

not have been extended to others, until the first group to be

treated had gone through the entire cycle of convalescence,

which involved several days of special treatment and care.

418. GRIMANI BREVIARY (1490-1510). ILLUMINATION FOR THE MONTH OF SEPTEMBER

VENICE, BIBLIOTECA DI SAN MARCO, FOL. 10

The breviary affords a painfully realistic view of a physician bleeding a patient. The Grimani Breviary, of uncertain authorship, provenance,

and even date, is one of the finest and most profusely illuminated manuscripts of its class; its 110 illuminations depict labors of the months and

numerous other scenes from daily life, religious festivals, feasts of the saints. The illuminations are from many different hands, mostly Flemish,

a few perhaps French; the style suggests a date nearer the start of the 16th century.

The word flebotomatus does not occur in the Rule; see the index of

words in Benedicti regula, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 175ff.

"Multum insipienter et indocte fecistis in luna quarta flebotomando.

Memini enim beatae memoriae Theodorum archiepiscopum dicere, quia

periculosa sit satis illius temporis flebotomia, quando et lumen lunae, et

reuma oceani in cremento est. Et quid ego possum puellae, si moritura est

facere?" Bede, Hist. Eccl., book V., chap. 3, ed. Plummer, I, 1896, 285;

ed. Colgrave and Mynors, 1969, 460-61. (The passage was brought to my

attention by C. W. Jones.)

De minutione sanguis, ed. Migne, Patr. Lat., XC, 1862, cols. 959-62.

With regard to the wrong attribution of this treatise to Bede see Jones,

1939, 88-89.

Synodi primae decr. auth., chap. 10, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 459-60. The matter had already been taken up in the preliminary

deliberation of this synod and had elicited some interesting remarks by

Bishop Haito: See Statuta Murbacensia, chap. 12, ed. Semmler, op. cit., 445-46.

MEDIEVAL PORTRAYALS OF BLEEDING

A marginal illustration in the Luttrell Psalter (fig. 417)

furnishes us with a realistic picture of the performance of

this ubiquitous craft. It shows a physician standing and

bleeding a patient from the right arm. The patient is seated

on a stool and holds a bowl in his left hand to catch the

blood. He keeps his right arm steady by propping it on a

staff or pole while the physician places his left foot on that

of the patient. This appears to have been a standard position

for this kind of operation. It occurs again, almost

feature by feature, in the representation of a similar scene

in the Grimani Breviary (fig. 418).[402]

In both cases the blood

is taken from the anticubital vein, in the crook of the elbow,

a preferred place for bloodtaking even today, since here one

of the principal veins comes close to the surface and exposes

itself in a relatively fixed position. The staff or pole, apart

from steadying the patient in a general sense, adds muscular

control to the operation, as it enables the patient to

increase or diminish the flow of blood by locking his fist

around the pole or conversely by relaxing his grip.

For the Luttrell Psalter, see Millar, 1932, pl. 16; for the Grimani

Breviary, see Morpurgo and de Vries, I, 1903, pl. 18.

PHLEBOTOMY: A MEDIEVAL PANACEA

Phlebotomy was a medical omnium-gatherum used for

curing a bewildering variety of ailments.[403]

The Regimen

sanitatis salernitanum, a widely read treatise on medicine,

written at the end of the eleventh century for Robert, Duke

of Normandy, the eldest son of William the Conqueror,

probably by John of Milan, head of the faculty of the School

of Medicine of Salerno at that time,[404]

defines its beneficial

effects as follows:

Phlebotomy clarifies the eyesight, strengthens mind and brain. It

warms the marrow, purges the intestines, forces stomach and

bowels into action. It purifies the senses, induces sleep, gives relief

from boredom. It restores and strengthens hearing, voice and

energy, facilitates speech, appeases ire, allays anxieties, and cures

watering eyes.[405]

The physician points out that the "superabundance of

spirit" (spiritus uberius) that escapes with the blood is

quickly replenished through the drinking of wine, while

the weakness of the body sustained by bleeding is gradually

repaired by the intake of food.

For a general review of the practice of bloodletting, see MacKinney,

1937, 39ff., and Gougaud, 1930, 49-68.

For date and authorship, see Packard's introduction to Regimen

sanitatis salernitanum, 1920, 24ff.

My prose translation follows the text published by Saint-Marc,

1880, 213-14, which is a little longer than the text published by Packard,

op. cit., 176.

FROM PHYSICIAN TO BARBER

There is no reason to presume that in the early Middle

Ages bloodletting was performed by persons other than

trained physicians. Alcuin and Walahfrid Strabo refer to

the practice as being performed by medici.[406]

But in the later

Middle Ages physicians considered this operation to be

beneath their dignity and conceded it to "barbers" and

"professional bleeders" (rasatores et sanguinatores).[407]

In the

twelfth century this change must have been well under way.

A hint of the social milieu from which such secular bleeders

may have emerged and how and where they may have

received their training is found in the Chronicle of the

Abbey of St. Trond, where it is said of one of the monastery's

serfs, a recalcitrant oppidanus (inhabitant of a city)

named Arnulf, that in return for the terms of a tenement

granted to him by the abbey, he was not only to assist the

monks whenever they were bled, but in addition to provide

for the abbot's saddle and spurs, repair the abbey's window,

and perform other minor services, such as keeping all of

the monastery's locks in working condition.[408]

Rudolfi Gesta abbatum Trudonensium, Book IX, chap. 12, ed,

Koepke, in Mon. Germ. Hist., Scriptores, X, 1852, 284. The passage

refers to the period 1108-32: "Oppidanus quidam noster Arnulfus nomine

patris quod sui Baldrici imitatus violentiam, terram tenera volebat sine

servitio, quae debet servire fratribus ad omnem minutionem sanguinis

eorum debet et alia minuta servitia ad utensilia camerae abbatis,

scilicet quicquid de ferro ad sellam equitariam eius et ad calcaria et ad

saumas componitur, dato sibi ab abbate ferro. Fractas vitreas fenestras

monasterii, claustri, cellae abbatis, accepto et custode vitro, plumbo et

stagno et caere et sumptu emendat. Claves omnes monasterii et scriniorum,

dato sibi ferro, novat et renovat, similiter et de omnibus officinis claustri et

curtis.

RELIEF FROM DREARINESS OF DAILY ROUTINE

Dom D. Knowles attributes the phenomenal spread of

the practice of bloodletting in monastic life to the "general

feeling of physical malaise" brought about by an unbalanced

diet and the sedentary life of the monks, calling for

some violent form of relief.[409]

One of the attractive features

of its practice was that it gave relief from the dreariness of

the daily routine and was associated with a fortifying regime

of food, allowed in compensation for the loss of blood. This

gave to the occasion a touch of recreative pleasure, which

monastic discipline found it difficult to repress.

RULES TO BE FOLLOWED IN THE PRACTICE

OF BLEEDING

A detailed account of special rules to be followed in the

practice of bleeding will be found in Ulric's Antiquiores

consuetudines (d. 1093) of the Monastery of Cluny[410]

and the

chapter "Permission for Being Bled" in the Monastic

Constitutions of Lanfranc.[411]

From a review of these, and a

variety of other sources,[412]

the routine of the monk who subjected

himself to bloodletting went as follows:

After having obtained formal permission to be bled

(licentia minuendi) by petition to the chapter, the brother

left the church at the end of the principal mass and went to

the dormitory to exchange his vestments of the day (diurnales)

for his clothing of the night (nocturnales) which he

retained for the three days of rest that followed his operation.

The operation was initiated with a brief prayer which

began with the verse Deus in adjutorium meum intende. (In

the Benedictine monastery this prayer was preceded by an

inclination of the body called ante et retro.) The incision

was made in the morning, save for the time of Lent, when

it was done after vespers. The patients were issued bandages

of linen (fasciae, ligaturae, ligamenta brachiorum, bendae,

arcedo) with which to wrap their arms. Some consuetudinaries

recommend that before being bled a monk should

pass by the kitchen to have his arm warmed.

During recovery the patients were not held to their

regular duties in the choir, but had leave to rise later than

the others and to recite only a part of the divine office.

Moreover, they were at liberty to take walks in the monastery's

vineyards and meadows. Their diet, as already

mentioned, made allowance not only for the ordinarily forbidden

meats, but also for greater abundance. During the

periods when the rest of the community ate only one meal,

the frater minuendus ate two; on all other occasions, three:

the mixtum, the prandium and the coena.

It is obvious that in view of all these special privileges,

bloodletting acquired an attraction that in the minds of

some of the more conservative members of the community

bordered on dissipation; and the monastic consuetudinaries,

indeed, abound with admonitions aimed at curtailing

the spread of merriment, if not of outright breaches of

discipline, with which this activity tended to be associated.

A main concern of those who were in charge of monastic

discipline was to prevent the seynies from coinciding with

important religious festivities; others felt it necessary to

restrict the repetition of the privilege to certain cycles. The

monastery of St. Augustine in Canterbury allowed the

monks to be bled in intervals of seven weeks; at Ely the

interval was six; in other monasteries it was only five or

four times per year that a monk could be bled.

The reconstruction of the House for Bloodletting poses

problems of a special kind. Safety of construction, in the

presence of so many corner fireplaces, requires that its

walls be built in masonry. The house is not inhabited by

any permanent residents and serves one purpose only:

bleeding and recovering from this treatment. There is no

need for the designation of any internal boundaries between

the primary function of the building and such subsidiary

functions as sleeping or stabling animals which in the plans

of other buildings led to the delineation of aisles and leanto's;

and this is the reason, in our opinion, why the drafting

architect showed it as a unitary all-purpose space. Yet the

size of the building argues against the assumption that it

was surmounted by a roof that spanned the entire width of

the house in a single span. For the nave of a church a roof

span of 35 feet would be normal practice in this period, but

in a simple service structure it would be an anomaly. We

have introduced in our reconstruction of the House for

Bloodletting two inner ranges of roof-supporting posts

whose presence cannot be proven from the simple analysis

of the plan of this building.[413]

SITE PLAN

Antiqiuores consuetudines Cluniacensis monasterii, collectore Udalrico

Monacho Benedictino, Book. 11, chap. 21, ed. Migne, Patr. Lat., CXLIX

1882, cols. 709-10.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||