The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V. 2. |

| V. 3. |

| V. 4. |

| V. 5. |

| V. 6. |

| V. 7. |

| V. 8. |

| V. 9. |

| V. 10. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V. 13. |

| V. 14. |

| V. 15. |

| V. 16. |

| V. 17. |

| V. 18. |

| VI. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.8.6

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

THE KING'S CLAIM ON MONASTIC HOSPITALITY

To the north of the Church in a large enclosure, which

forms the counterpart to the court of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers, is a house whose elaborate layout

reveals it to be a guesthouse for visitors of unusual stature.

It is here that the traveling emperor or king was received,

his court or his agents (missi), and also, perhaps, the visiting

bishops and abbots.

The king's right to draw on the hospitality of the monasteries

for food and quarters while traveling dates back to

the early days of the introduction of monastic life in transalpine

Europe. But the use that the rulers made of it in the

time of the Carolingians was considerably more burdensome

than it had been under the Merovingians.[305]

Ever-changing

political necessities, the protection of the boundaries, the

maintenance of peace in the interior, prevented the emperor

from establishing a permanent residence. "Performing his

high craft by constantly shifting around,"[306]

he moved from

one of his royal estates to the other—making full use of the

obligations of the abbots and bishops to provide him with

lodging—according to the circumstances that his itinerary

imposed upon him, or simply in response to the necessity

of finding additional subsistance for himself and his court.

The primary motivations for such visits were not always of

an economic or military nature. Gauert's analysis of

Charlemagne's itinerary has shown that the emperor's general

travel schedule often had embedded in it a special

"Gebetsitinerar," at times involving lengthy detours for

visits to religious places where the emperor went primarily

for the purpose of prayer, to participate in important religious

festivals, or to venerate the local saints.[307]

The heaviness

of the economic obligations that a monastery took upon

itself on such occasions depended on the frequency of the

visits, the length of the emperor's stay, and the size of his

retinue. Charlemagne and Louis the Pious availed themselves

of monastic hospitality with discretion; under the

later Carolingian kings the burden became heavier.[308]

But

even as early as the second decade of the ninth century the

sum of monastic obligations in hospitality had reached proportions

so heavy as to drive the witty abbot Theodulf,

Bishop of Orléans, to remark desperately that had St.

Benedict known how many would come, "he would have

locked the doors before them."[309]

To use a phrase coined by Schulte, 1935, 132. For the ambulatory

life of medieval kings in general, see Peyer, 1964.

For more details cf. Lesne's informative chapter on monastic

hospitality extended to kings and their representatives, (Lesne, II,

1922, 287ff.) and Voigt's remarks on the increasingly intolerable economic

burden royal visits imposed upon the abbeys, bishoprics and counties

under the reign of Charles the Bald and Louis the German (Voigt,

1965, 27ff). When Louis the German invaded the empire of the West-Franks

in 858, the bishops, in a petition drafted by Hincmar of Reims,

beseeched the emperor to bolster his economic capabilities through

more efficient management of the crown estates, rather than by depleting

the resources of the abbots, bishops and counts for the sustenance of his

traveling court. They made a plea that their contribution to the maintenance

of the emperor's train be reduced to the share customary during

the reign of his father, Louis the Pious. (Epistola synodi Cariasiacensis

ad Hludowicum regem Germaniae directa, chap. 14, ed. Krause, Mon.

Germ. Hist. Legum Sec. II, Capit. Reg. Franc., II, Hannover, 1897,

437). In a subsequent letter written to Charles the Bald, Hincmar informed

the latter that the substance of his petition to Louis the German

was, in an even more urgent sense, addressed to him (ibid., 428).

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 501: "Per Deum, si

nunc adesset S. Benedictus, claudere illis ostium fecisset".

THEIR MAGNITUDE: A REFLECTION OF THE CLOSE

ALLIANCE OF CHURCH AND STATE

The Plan of St. Gall provides for four separate houses

for the reception of royal visitors: 1, a house for the emperor

and his immediate entourage; 2, an ancillary building

containing the kitchen, bake, and brewing facilities pertaining

to this house; 3, a House for Visiting Servants; and,

if my interpretation is correct, 4, a house for the emperor's

vassals and others of knightly rank traveling in the emperor's

train. Plans, sections, reconstructions, and authors'

interpretations for these facilities are shown in figures

396-406.

The total surface area taken up by these houses and their

surrounding courts amounted to 1,360 square feet, or a

little over one-fifth of the surface area of the entire monastery

complex.

The presence of obligatory royal quarters of such magnitude

within the precincts of the monastery is a reflection of

the close alliance that had been struck in the kingdom of the

Franks between the concepts of regnum and sacerdotium, a

development that started with the sanctioning of the Carolingian

house by Pope Zacharias in 751 and reached its

apex with the coronation of Charlemagne in the year 800.

As the appointed successor of the emperors of Rome,

Charlemagne had taken upon himself not only the duty of

protecting the Church in a physical sense, but also the

obligation of safe-guarding its institutions, regulating the

life and education of the clergy, and even ruling in questions

of liturgy and dogma.[310]

It is fully understandable that

within the context of a political philosophy so replete with

religious overtones the emperor's presence in the monastery

was as yet not considered a worldly infraction on

monastic peace and seclusion.

On this aspect of the emperor's responsibilities, see A. Schmidt,

1956, 348; Ganshof, 1960, 96 and Ganshof, 1962, 92.

THE MAIN HOUSE

Layout and function

The general purpose of the House for Distinguished

Guests is defined by a hexameter which reads:

domus

Haec quoque hospitibus parta est quoque suspicientis[311]

This building, too, serves for the reception of guests

The conjunction quoque suggests that the building holds a

position of secondary importance with regard to another

facility for guests, which can only be the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers. The modest slant of this verse is obviously

a reflection of the warning given by St. Benedict

that the hospitality accorded to the poor lies on a higher

plane of religious devotion than that extended to the rich.[312]

But the profuse attention lavished on the internal layout of

the House for Distinguished Guests tends to defy this

thought.

The House is 67½ feet long and 55 feet wide. It has as its

principal room a large rectangular hall, which its explanatory

title defines as the "dining hall of the guests" (domus

hospitū ad prandendum). Access to this is gained through a

402. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR SERVANTS OF OUTLYING ESTATES AND FOR SERVANTS

TRAVELING WITH THE EMPEROR'S COURT (NOT CERTAIN: cf. BUILDING 34)

The house is one of four identical buildings located to the right of the entrance

road where most of the monastery's livestock is kept. Its large central hall, like

those of many other buildings of this group, is referred to as DOMUS, a term used

by the drafters of the Plan not to designate the entire house (as its classical usage

would prescribe), but as a name for the common living room where men gather

around the open fireplace for conversation and meals. The spaces in the aisles

and under the lean-to's are used for sleeping and for the stabling of livestock.

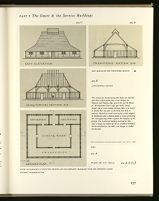

PLAN OF ST. GALL

403.C

403.D EAST ELEVATION AND TRANSVERSE SECTION

403.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

The criteria for reconstructing this house are identical

with those which guided that of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers (figs. 393.A-E) and the House

for Distinguished Guests (figs. 397.A-F). Being

smaller and of more modest purpose, there is no reason

to assume that any part of the house was built in

masonry, beyond (as sound construction would suggest)

its foundation and a shallow plinth of stones protecting

the roof-supporting timbers against the dampness of the

ground. The traditional building material for this

type of house was timber for all its structural members,

wattle-and-daub for the walls, and shingles or shakes

for the roof.

403.A PLAN

HOUSE FOR SERVANTS OF OUTLYING ESTATES AND FOR SERVANTS TRAVELING WITH THE EMPEROR'S COURT

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

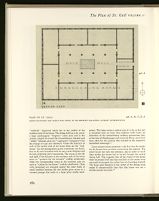

404. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

Its identification must remain tentative, for the lines and titles of this building were erased in the 12th century by a monk who wrote a Life

of St. Martin on the verso of the Plan, spilling the last 22 lines of text onto the plan of this house. The few fragments of titles that escaped

his knife were obliterated in the 19th century by an attempt to restore them with a chemical substance that left only coarse blotches on the

parchment wherever it was applied.

405. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

X-rays revealed the outlines of a colossal variant of the standard house of the Plan, with an entrance in one narrow side. Comparison with

other similar buildings leaves no doubt that the large center room was intended as a common hall for living and dining, with peripheral spaces

serving partly for bedrooms, partly for stables.

406.A PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

southern aisle of the house. The dining hall has in its center

a large quadrangular "fireplace" (locus foci) and in the

corners, ranged all around the circumference, benches and

"tables" (mensae), plus two "cupboards" (toregmata[313] ) for

the storage of cups and tableware. Under the lean-to's at

each of the narrow ends of the house there are the "bedrooms"

for the distinguished guests (caminatae cum lectis),

four in all, each furnished with its own corner fireplace and

its own projecting privy (necessariü). The rooms to the left

and right of the entrance in the southern aisle of the house

serve as "quarters for the servants" (cubilia seruitorum),

while two corresponding rooms in the northern aisle are

used as "stables for the horses" (stabula caballorum). Their

cribs (praesepia) are arranged against the outer walls. A

small vestibule between the two stables gives access to a

covered passage that leads to a large privy (exitus neces-

sarius). The latter covers a surface area of 10 by 45 feet and

is furnished with no fewer than eighteen toilet seats—an

indication of the extraordinary sanitary precautions that,

at the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, must have

been taken for the persons who traveled in the emperor's

immediate entourage.[314]

I have already drawn attention to the fact that the stables

for the horses have no direct access from the exterior. The

entire house has only one entrance, and in order to reach

their stables the horses had to be led through the central

dining hall. This suggests that all the rooms of the house

were on ground level and that the floor of the center room

was made of stamped clay rather than of a boarding of wood.

The large open fireplace in the center of the dining room

makes it unequivocably clear that this house was not a

double-storied structure.[315]

406.B

By making the center hall of this building 45 feet wide by 60 feet long, the drafters of the Plan pushed the structural capabilities of the aisled

Germanic all-purpose house to its limits. Spans of 45 feet, rare even in church construction, were unheard-of in domestic architecture. We

know of only one other medieval building of even comparable dimensions: the barn of the abbey grange of Parçay-Meslay, France (figs. 352-355)

at a width of 80 feet. But the vast roof of that barn is supported, not by the traditional two, but by four rows of freestanding inner posts.

We do not believe that the roof of the House for Knights and Vassals could have been supported successfully by less posting and have therefore

introduced in our reconstruction two additional rows of posts, that reduce the center span of the inner hall from 45 to a more conventional

27 feet.

Incorporating the doubled rows of posting is not in conflict with methods of architectural rendering employed by the drafters of the Plan.

They were not concerned with constructional details, but primarily with establishing the boundaries of each building on the site in terms of its

function and its components. The size of a royal retinue—including its servants, grooms, bodyguard, as well as the principals themselves—

justifies the tentative identification of this house.

In this, as in other buildings of the Plan, details of construction engineering were left to be resolved by the ingenuity of a master builder who

would determine in what ways a building conceived for the purpose of housing up to 40 men and 30 horses, and their attendants, could be

realized as functional architecture. The interaction of planners with builders is elsewhere attested on the Plan, wherever features obviously

intended and needed are absent: staircases, doors and windows, and others (see I. 13, 65ff).

The main point of interest, we believe, in our investigation of this particular building is that the prevailing building type of the Plan of St. Gall,

the three-aisled hall—without loss of the essence of its character—adapts with ease and dignity and possibly with some elegance, to a building of

relatively inordinate size through the device of adding an aisle between the central main space of the nave, and each of the lean-to side aisles.

In effect, a five-aisled hall is thus formed (see fig. 354.A, B, Parçay-Meslay, and Les Halles, Côte St. André, Isère, France).

In writing this line the scribe had started Haec quoque hospitibus . . . ,

but struck out the word quoque and replaced it by domus, when he

discovered that quoque appeared twice in his line. The mistake is interesting,

because it shows how strongly the shaper of this hexameter was

preoccupied with the content attached to the conjunction quoque.

All these features were of primary importance in our analysis of the

building type, cf. above, pp. 82ff and 115ff.

Materials and mode of construction

In contrast to the Abbot's House,[316]

whose typological

roots lie in the South, the House for Distinguished Guests,

as has been demonstrated, is a descendant of a strictly

Northern building type. It may have been built entirely

in wood, or it may have had its circumference walls constructed

in masonry. In our reconstructions (figs. 397-399)

we have chosen this latter solution in order to demonstrate

the possibility of mixed materials on this higher social level

of building. In the interior the roof must have been supported

by two parallel rows of wooden posts, framed into

weight- and thrust-resisting trusses with the aid of tie

beams and post plates. If the roof belonged to the purlin

family of roofs, its basic design cannot have differed greatly

from what we have suggested in figures 397 and 398. For

the thirteenth century this type of roof is well attested, at

least on the Continent, as has been demonstrated by the

examples discussed above on pages 88ff. It may have been

as common in Carolingian times.

That royal timber houses with masonry walls existed in

Carolingian times is known through the Brevium exempla,

for it is doubtlessly to this mixture of materials that the

author of this work refers, when describing the domus

regalis of one of his anonymous crown estates as a house that

was "externally built in stone, and inside all in timber"

(exterius ex lapide et interius ex ligno bene constructam).[317]

PLAN OF ST. GALL

406.C

NORTH ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

Separation of common & private rooms

The internal layout of the House for Distinguished

Guests (fig. 398) is historically of particular interest, as it

shows that at the beginning of the ninth century the timbered

royal hall was sufficiently partitioned internally to

allow the lord to withdraw from the ranks of his followers

to the privacy of separate bedrooms. Dining was still a

communal function. But the establishment of individual

fireplaces with chimneys in the lord's private chambers

made the latter independent from the open fire in the floor

of the hall. Architecturally speaking, this means that the

private bedrooms under the lean-to's at each end of the

hall could have been screened off from the rest of the

building, not only by vertical wall partitions (as they most

certainly were), but also by their own individual ceilings.

If ceilings were installed, the walls required windows,

since ceilings would have deprived the bedrooms of the

principal source of light for the house—the louver over the

fireplace in the ridge of the roof of the hall. The quarters

of the servants, on the other hand, cannot have been provided

with ceilings, since they depended for warmth on the

heat furnished by the communal fire in the center hall.

Housing capacity

The House for Distinguished Guests can accommodate

eight visitors of rank in four separate rooms, each of which

is furnished with two beds, two benches, and a corner

fireplace.[318]

These are the rooms for the emperor, the empress,

or any other members of the imperial family who

accompanied the emperor on his travels, and some of the

highest ranking ministers and councilors who were part of

the emperor's permanent staff. The rooms for the servants

in the southern aisle of the house have a bedding capacity

for eighteen men. This is the number of beds of standard

size that could be set up for the servants if they were ranged

peripherally along the walls of their rooms (nine in each).

Eighteen also happens to be the number of toilet seats

available in the servant's privy. The two stables in the

northern aisle of the house can accommodate four horses

406.D

TRANSVERSE SECTION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

7½ feet long). These must have been the mounts of the distinguished

guests, since their number corresponds exactly

to the number of beds available in the latter's private

chambers.

Even the seating capacity of the dining room is closely

correlated with the total number of men who can be accommodated

in the House for Distinguished Guests. The

eastern or upper end of the hall is furnished with two short

straight tables, each capable of seating four of the eight

distinguished guests (if we attribute to each of them a sitting

area 2½ feet wide). The western or lower end has longer,

L-shaped tables with sufficient sitting space to take care of

the eighteen servants.

Stephani's account of the bedding capacity of the private rooms for

the distinguished guests is wrong ("Jedes Schlafzimmer sieht sechs

Schlafbänke und ein zu wenigstens noch zwei weiteren Personen Raum

bietendes Doppelbett vor, will also zumindest acht Personen Aufnahme

gewähren"); see Stephani, II, 1903, 32-33. The benches on either side

of the corner fireplace are for sitting, not for sleeping. They are too short

to be interpreted as beds.

Number and composition of officers of state

in the emperor's train

There are no conclusive studies on the number or composition

of the officers of state who accompanied the emperor

on his travels.[319]

From Hincmar's account of Adalhard

of Corbie's De Ordine Imperii,[320]

it appears that the central

administrative body of the Carolingian court consisted of a

staff of six leading functionaries, who by the very definition

of their office were part and parcel of the emperor's personal

entourage, viz., the Seneschal (senescalcus, literally,

"the old servant") who was in charge of provisions and

especially those of the royal table; the Butler (buticularius),

406.E PLAN OF ST. GALL

EAST ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

charge of lodging and the royal treasury; the Constable

(comes stabuli) in charge of horses and all other means of

transportation; the Count Palatine (comes palatinus), the

primary officer in charge of the empire's judiciary administration;

and last but not least, the Arch Chaplain (summus

capellanus), the emperor's primary advisor in ecclesiastical

and educational matters, whose office later became absorbed

in that of the Chancellor (summus sacri palatii cancellarius).[321]

Readiness for action involving the state and the imperial

household in its entirety would have required the presence

of all these men. But it is well known that the holders of

these offices were often away from the court in the summer

on special missions.[322] The House for Distinguished Guests,

nevertheless, would have been equipped to accommodate

all these men besides the emperor himself, plus his wife or

one of his children. How many members of his family he

was wont to have with him when traveling is another

question for which we have no ready answer. "Charlemagne,"

we are told by Einhard, "cared so deeply for the

training of his children that he never took his meal without

them when he was at home, and never made a journey

without them."[323] Although this could scarcely have applied

to all the seven sons and daughters[324] that Einhard ascribes

to Charlemagne, it would still suggest that the traveling

emperor was frequently accompanied by one or another of

his sons and daughters.[325] When Louis the Pious stayed in

St. Gall in 857, his sons Karlmann and Karl III were with

him.[326] This is about all that seems to be known on this

subject.

The Plan of St. Gall may actually help us here to close a

gap of knowledge. It discloses that at the time of Louis the

Pious a monastery was expected to be capable of taking care

of a royal party consisting of eight dignitaries of state or

members of the imperial family, their mounts, and eighteen

of their personal servants. In later centuries the figure may

have been considerably larger. The Consuetudinary of

Farfa—in reality the customs of Cluny (written between

house for forty male and thirty female members of the

emperor's train, plus a stable capable of sheltering some

150 horses.[327] Yet conditions at Cluny were probably

unusual. A fulcrum of revival and reform among the

monasteries of France and unbelievably rich, the abbey

was already well on its way toward wedging itself as an

arbitrating spiritual force into the interplay between the

secular and the ecclesiastical powers of the period.

A systematical study of the signatures attached to imperial deeds,

issued as the emperor moved from place to place, may help to clarify

this problem.

Cf. Ganshof's remarks on the "aulic" nature of this staff of officers

and their respective duties, Ganshof, 1958, 47-48; 1962, 99-100; 1965,

361ff. On the ambivalence of the offices of the summus capellanus and

summus cancellarius, see Klewitz, 1937, 52-55.

For a recent study on the court of Charlemagne and its fluctuating

composition, see Fleckenstein, 1965.

Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, ed. Garrod and Mowat, 1915,

23-25; Éginhard, Vie de Charlemagne, ed. Halphen, 1923, 60-61; The

Life of Charlemagne by Einhard, ed. Painter, 1960, 48. The phrase is

fashioned after a passage in Suetonius' Life of the Emperor Augustus.

On the veracity of Einhard's testimony even where it is couched

in literary imagery borrowed from Suetonius, see Beumann, 1951,

1962; and Fleckenstein, 1965, 24ff.

Notkeri Gesta Karoli, Book I, chap. 34, ed. Rau, in Quellen zur

Karolingischen Reichsgeschichte, III, 1960, 374-75.

Consuetudines Farfenses, Book II, chap. 1, ed. Albers, in Cons. Mon.,

I, 1900, 138. Cf. below, pp. 277, 306. The stable for the horses was

280 feet long and 25 feet wide. Counting a standing area of 5 by 7½ feet

per horse, this house would shelter 152 horses stabled in opposite rows

along the two long walls of the structure. From this figure, of course,

one would have to subtract a certain number, as some of the space in the

walls must have been taken up by entrances. The second story of this

stable house contained the eating and sleeping quarters of the riding

members of the emperor's train, who could not be accommodated in the

house of the noblemen and their ladies. In addition to the mounted

following there was also a train of unmounted men.

Other supporting forces

Even in the ninth century, nevertheless, a guest house

with a bedding capacity of eight distinguished guests, their

horses, and eighteen of their servants, is not likely to have

been capable of accommodating the whole of the emperor's

permanent train. To be protected, the king needed a bodyguard.

Such a guard of mounted knights would not necessarily

have had to be very large, yet it is unlikely to have

consisted of fewer than twenty or thirty men. They, too, and

their horses would have to be provided with quarters. One

would have to expect, additionally, a small train of wagons

with emergency rations, kitchens, tents, and other equipment

indispensable to the movement of the court. This

involved another troup of servants who would also have to

be sheltered. The Plan of St. Gall shows two buildings that

may have performed that function, located at the gate of the

monastery in the immediate vicinity of the House for Distinguished

Guests. But before we turn to them, some attention

must be paid to the kitchen, bake, and brewing facilities

of the House for Distinguished Guests.

KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREW HOUSE FOR

THE DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

The main portion of this structure, which covers an area

roughly 50 by 55 feet (figs. 396, 400-401), is identical

with that of the Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims and

Paupers (fig. 392). But its outside appearance must have

been quite different, as it had attached to it on the side facing

the House for Distinguished Guests, two large rectangular

rooms (17½ feet by 22½ feet); one of which served as the

guests' kitchen (culina hospitū), the other as "larder"

(promptuariū). The kitchen stove, a square of 5 by 5 feet, is

subdivided into four cooking areas by two median lines that

bisect it at right angles. The principal space of the house,

measuring 20 by 55 feet, contains in its southern half the

"bakery" (pistrinum) with its "oven" (fornax), two kneading

troughs (not designated as such by inscriptions), and

all around the periphery of the room, the indispensable

tables for the shaping and laying out of the loaves. The

northern half contains the brew house (domus conficiendae

celiae) with fires and coppers for malting the grain (fig.

401A). The aisle in the rear of the house is subdivided into

two equal parts, each serving as an accessory to the work

carried on in the corresponding portion of the principal

space of the house. The room near the bakery is designated

as "the place where dough is made [by mingling flour with

water]" (interndae pastae locus) and for that purpose it is

furnished with a long trough and a circular vat. The other

near the brewery, is described as the place where the brew is

"cooled" (hic refrigeratur ceruisa). It is equipped with two

smaller troughs that stand on either side of a circular vat.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||