74. CHAPTER LXXIV.

MIDNIGHT.

Gradually the sneer faded from Abel's face, and he walked

up and down the room, no longer carelessly, but fitfully; stopping

sometimes—again starting more rapidly—then leaning

against the mantle, on which the clock pointed to midnight—

then throwing himself into a chair or upon a sofa; and so,

rising again, walked on.

His head bent forward—his eyes grew rounder and harder,

and seemed to be burnished with the black, bad light; his

step imperceptibly grew stealthy—he looked about him carefully—he

stood erect and breathless to listen—bit his nails,

and walked on.

The clock upon the mantle pointed to half an hour after

midnight. Abel Newt went into his chamber and put on his

slippers. He lighted a candle, and looked carefully under the

bed and in the closet. Then he drew the shades over the

windows and went out into the other room, closing and locking

the door behind him.

He glided noiselessly to the door that opened into the entry,

and locked that softly and bolted it carefully. Then he turned

the key so that the wards filled the keyhole, and taking out

his handkerchief he hung it over the knob of the door, so that

it fell across the keyhole, and no eye could by any chance have

peered into the room.

He saw that the blinds of the windows were closed, the

windows shut and locked, and the linen shades drawn over

them. He also let fall the heavy damask curtains, so that the

windows were obliterated from the room. He stood in the

centre of the room and looked to every corner where, by any

chance, a person might be concealed.

Then, moving upon tip-toe, he drew a key from his pocket

and fitted it into the lid of a secretary. As he turned it in

the lock the snap of the bolt made him start. He was haggard,

even ghastly, as he stood, letting the lid back slowly, lest

it should creak or jar. With another key he opened a little

drawer, and involuntarily looking behind him as he did so, he

took out a small piece of paper, which he concealed in his hand.

Seating himself at the secretary, he put the candle before

him, and remained for a moment with his face slightly strained

forward with a startling intentness of listening. There was

no sound but the regular ticking of the clock upon the mantle.

He had not observed it before, but now he could hear nothing

else.

Tick, tick — tick, tick. It had a persistent, relentless, remorseless

regularity. Tick, tick—tick, tick. Every moment it

appeared to be louder and louder. His brow wrinkled and

his head bent forward more deeply, while his eyes were set

straight before him. Tick, tick—tick, tick. The solemn beat

became human as he listened. He could not raise his head—

he could not turn his eyes. He felt as if some awful shape

stood over him with destroying eyes and inflexible tongue.

But struggling, without moving, as a dreamer wrestles with

the nightmare, he presently sprang bolt upright—his eyes wide

and wild—the sweat oozing upon his ghastly forehead—his

whole frame weak and quivering. With the same suddenness

he turned defiantly, clenching his fists, in act to spring.

There was nothing there. He saw only the clock—the gilt

pendulum regularly swinging—he heard only the regular tick,

tick—tick, tick.

A sickly smile glimmered on his face as he stepped toward

the mantle, still clutching the paper in his hand, but crouching

as he came, and leering, as if to leap upon an enemy unawares.

Suddenly he started as if struck—a stifled shriek of

horror burst from his lips—he staggered back — his hand

opened—the paper fell fluttering to the floor. Abel Newt

had unexpectedly seen the reflection of his own face in the

mirror that covered the chimney behind the clock.

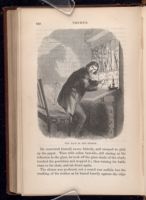

[ILLUSTRATION]

The Face In The Mirror.

[Description: 538EAF. Page 420. In-line Illustration. Image of a man at a desk. He is standing but slightly bent over. He has a key in one hand and is reaching towards a drawer while looking over his shoulder. There is a candle on the desk that casts a large shadow of the man on the wall behind him.]

He recovered himself, swore bitterly, and stooped to pick

up the paper. Then with sullen bravado, still staring at his

reflection in the glass, he took off the glass shade of the clock,

touched the pendulum and stopped it; then turning his back,

crept to his chair, and sat down again.

The silence was profound, not a sound was audible but the

creaking of his clothes as he leaned heavily against the edge

of the desk and drew his agitated breath. He raised the candle

and bent his gloomy face over the paper which he held

before him. It was a note of his late firm indorsed by Lawrence

Newt & Co. He gazed at his uncle's signature intently,

studying every line, every dot—so intently that it seemed

as if his eyes would burn it. Then putting down the candle

and spreading the name before him, he drew a sheet of tissue

paper from a drawer and placed it over it. The writing was

perfectly legible—the finest stroke showed through the thin

tissue. He filled a pen and carefully drew the lines of the

signature upon the tissue paper—then raised it—the fac-simile

was perfect.

Taking a thicker piece of paper, he laid the note before him,

and slowly, carefully, copied the signature. The result was a

resemblance, but nothing more. He held the paper in the

flame of the candle until it was consumed. He tried again.

He tried many times. Each trial was a greater success.

Tearing a check from his book he filled the blanks and

wrote below the name of Lawrence Newt & Co., and found,

upon comparison with the indorsement, that it was very like.

Abel Newt grinned; his lips moved: he was muttering “Dear

Uncle Lawrence.”

He stopped writing, and carefully burned, as before, the

check and all the paper. Then covering his face with his

hands as he sat, he said to himself, as the hot, hurried

thoughts flickered through his mind,

“Yes, yes, Mrs. Lawrence Newt, I shall not be master of

Pinewood, but I shall be of your husband, and he will be master

of your property. Practice makes perfect. Dear Uncle

Lawrence shall be my banker.”

His brain reeled and whirled as he sat. He remembered

the words of his friend the General: “Abel Newt was not

born to fail.”

“No, by God!” he shouted, springing up, and clenching his

hands.

He staggered. The walls of the room, the floor, the ceiling,

the furniture heaved and rolled before his eyes. In the wild

tumult that overwhelmed his brain as if he were sinking in

gurgling whirlpools—the peaceful lawn of Pinewood—the fight

with Gabriel—the running horses—the “Farewell forever, Miss

Wayne”—the shifting chances of his subsequent life—Grace

Plumer blazing with diamonds—the figure of his father drumming

with white fingers upon his office-desk—Lawrence and

Gabriel pushing him out—they all swept before his consciousness

in the moment during which he threw out his hands wildly,

clutched at the air, and plunged headlong upon the floor,

senseless.