72. CHAPTER LXXII.

GOOD-BY.

The happy hours of Hope Wayne's life were the visits of

Lawrence Newt. The sound of his voice in the hall, of his

step on the stair, gave her a sense of profound peace. Often,

as she sat at table with Mrs. Simcoe, in her light morning-dress,

and with the dew of sleep yet fresh upon her cheeks,

she heard the sound, and her heart seemed to stop and listen.

Often, as time wore on, and the interviews were longer and

more delayed, she was conscious that the gaze of her old

friend became curiously fixed upon her whenever Lawrence

Newt came. Often, in the tranquil evenings, when they sat

together in the pleasant room, Hope Wayne cheerfully chatting,

or sewing, or reading aloud, Mrs. Simcoe looked at her

so wistfully—so as if upon the point of telling some strange

story—that Hope could not help saying, brightly, “Out with

it, aunty!” But as the younger woman spoke, the resolution

glimmered away in the eyes of her companion, and was succeeded

by a yearning, tender pity.

Still Lawrence Newt came to the house, to consult, to inspect,

to bring bills that he had paid, to hear of a new utensil

for the kitchen, to see about coal, about wood, about iron, to

look at a dipper, at a faucet—he knew every thing in the house

by heart, and yet he did not know how or why. He wanted

to come—he thought he came too often. What could he do?

Hope sang as she sat in her chamber, as she read in the

parlor, as she went about the house, doing her nameless, innumerable

household duties. Her voice was rich, and full, and

womanly; and the singing was not the fragmentary, sparkling

gush of good spirits, and the mere overflow of a happy temperament—it

was a deep, sweet, inward music, as if a woman's

soul were intoning a woman's thoughts, and as if the woman

were at peace.

But the face of Mrs. Simcoe grew sadder and sadder as

Hope's singing was sweeter and sweeter, and significant of

utter rest. The look in her eyes of something imminent, of

something that even trembled on her tongue, grew more and

more marked. Hope Wayne brightly said, “Out with it,

aunty!” and sang on.

Amy Waring came often to the house. She was older than

Hope, and it was natural that she should be a little graver.

They had a hundred plans in concert for helping a hundred

people. Amy and Hope were a charitable society.

“Fiddle diddle!” said Aunt Dagon, when she was speaking

of his two friends to her nephew Lawrence. “Does this brace

of angels think that virtue consists in making shirts for poor

people?”

Lawrence looked at his aunt with the inscrutable eyes, and

answered slowly,

“I don't know that they do, Aunt Dagon; but I suppose

they don't think it consists in not making them.”

“Phew!” said Mrs. Dagon, tossing her cap-strings back pettishly.

“I suppose they expect to make a kind of rope-ladder

of all their charity garments, and climb up into heaven that

way!”

“Perhaps they do,” replied Lawrence, in the same tone.

“They have not made me their confidant. But I suppose that

even if the ladder doesn't reach, it's better to go a little way

up than not to start at all.”

“There! Lawrence, such a speech as that comes of your

not going to church. If you would just try to be a little better

man, and go to hear Dr. Maundy preach, say once a year,”

said Mrs. Dagon, sarcastically, “you would learn that it isn't

good works that are the necessary thing.”

“I hope, Aunt Dagon,” returned Lawrence, laughing—“I

do really hope that it's good words, then, for your sake. My

dear aunt, you ought to be satisfied with showing that you

don't believe in good works, and let other people enjoy their

own faith. If charity be a sin, Miss Amy Waring and Miss

Hope Wayne are dreadful sinners. But then, Aunt Dagon,

what a saint you must be!”

Gradually Mrs. Simcoe was persuaded that she ought to

speak plainly to Lawrence Newt upon a subject which profoundly

troubled her. Having resolved to do it, she sat one

morning waiting patiently for the door of the library—in which

Lawrence Newt was sitting with Hope Wayne, discussing the

details of her household—to open. There was a placid air of

resolution in her sad and anxious face, as if she were only

awaiting the moment when she should disburden her heart of

the weight it had so long secretly carried. There was entire

silence in the house. The rich curtains, the soft carpet, the

sumptuous furniture—every object on which the eye fell,

seemed made to steal the shock from noise; and the rattle of

the street—the jarring of carts—the distant shriek of the belated

milkman—the long, wavering, melancholy cry of the

chimney-sweep—came hushed and indistinct into the parlor

where the sad-eyed woman sat silently waiting.

At length the door opened and Lawrence Newt came out.

He was going toward the front door, when Mrs. Simcoe rose

and went into the hall, and said, “Stop a moment!”

He turned, half smiled, but saw her face, and his own settled

into its armor.

Mrs. Simcoe beckoned him toward the parlor; and as he

went in she stepped to the library door and said, to avoid interruption,

“Hope, Mr. Newt and I are talking together in the parlor.”

Hope bowed, and made no reply. Mrs. Simcoe entered the

other room and closed the door.

“Mr. Newt,” she said, in a low voice, “you can not wonder

that I am anxious.”

He looked at her, and did not answer.

“I know, perhaps, more than you know,” said she; “not,

I am sure, more than you suspect.”

Lawrence Newt was a little troubled, but it was only evident

in the quiet closing and unclosing of his hand.

They stood for a few moments without speaking. Then

she opened the miniature, and when she saw that he observed

it she said, very slowly,

“Is it quite fair, Mr. Newt?”

“Mrs. Simcoe,” he replied, inquiringly.

His firm, low voice reassured her.

“Why do you come here so often?” asked she.

“To help Miss Hope.”

“Is it necessary that you should come?”

“She wishes it.”

“Why?”

He paused a moment. Mrs. Simcoe continued:

“Lawrence Newt, at least let us be candid with each other.

By the memory of the dead—by the common sorrow we have

known, there should be no cloud between us about Hope

Wayne. I use your own words. Tell me what you feel as

frankly as you feel it.”

There was simple truth in the earnest face before him.

While she was speaking she raised her hand involuntarily to

her breast, and gasped as if she were suffocating. Her words

were calm, and he answered,

“I waited, for I did not know how to answer—nor do I

now.”

“And yet you have had some impression—some feeling—

some conviction. You know whether it is necessary that you

should come—whether she wants you for an hour's chat, as an

old friend—or—or”—she waited a moment, and added—“or

as something else.”

As Lawrence Newt stood before her he remembered curiously

his interview with Aunt Martha, but he could not say

to Mrs. Simcoe what he had said to her.

“What can I say?” he asked at length, in a troubled voice.

“Lawrence Newt, say if you think she loves you, and tell

me,” she said, drawing herself erect and back from him, as in

the twilight of the old library at Pinewood, while her thin

finger was pointed upward—“tell me, as you will be judged

hereafter—me, to whom her mother gave her as she died,

knowing that she loved you.”

Her voice died away, overpowered by emotion. She still

looked at him, and suspicion, incredulity, and scorn were mingled

in her look, while her uplifted finger still shook, as if appealing

to Heaven. Then she asked abruptly, and fiercely,

“To which, in the name of God, are you false—the mother

or the daughter?”

“Stop!” replied Lawrence Newt, in a tone so imperious

that the hand of his companion fell at her side, and the scorn

and suspicion faded from her eyes. “Mrs. Simcoe, there are

things that even you must not say. You have lived alone

with a great sorrow; you are too swift; you are unjust.

Even if I had known what you ask about Miss Hope, I am not

sure that I should have done differently. Certainly, while I

did not know—while, at most, I could only suspect, I could

do nothing else. I have feared rather than believed—nor that,

until very lately. Would it have been kind, or wise, or right

to have staid away altogether, when, as you know, I constantly

meet her at our little Club? Was I to say, `Miss Hope, I

see you love me, but I do not love you?' And what right

had I to hint the same thing by my actions, at the cost of utter

misapprehension and pain to her? Mrs. Simcoe, I do love

Hope Wayne too tenderly, and respect her too truly, not to

try to protect her against the sting of her own womanly pride.

And so I have not staid away. I have not avoided a woman

in whom I must always have so deep and peculiar an interest.

I have been friend and almost father, and never by a whisper

even, by a look, by a possible hint, have I implied any thing

more.”

His voice trembled as he spoke. He had no right to be silent

any longer, and as he finished Mrs. Simcoe took his hand.

“Forgive me! I love her so dearly—and I too am a woman.”

She sank upon the sofa as she spoke, and covered her face

for a little while. The tears stole quietly down her cheeks.

Lawrence Newt stood by her sadly, for his mind was deeply

perplexed. They both remained for some time without speaking,

until Mrs. Simcoe asked,

“What can we do?”

Lawrence Newt shook his head doubtfully.

They were silent again. At length Mrs. Simcoe said:

“I will do it.”

“What?” asked Lawrence.

“What I have been meaning to do for a long, long time,”

replied the other. “I will tell her the story.”

An indefinable expression settled upon Lawrence Newt's

face as she spoke.

“Has she never asked?” he inquired.

“Often; but I have always avoided telling.”

“It had better be done. It is the only way. But I hoped

it would never be necessary. God bless us all!”

He moved toward the door when he had finished, but not

until he had shaken her warmly by the hand.

“You will come as before?” she said.

“Of course, there will not be the slightest change on my

part. And, Mrs. Simcoe, remember that next week, certainly,

I shall meet Miss Hope at Miss Amy Waring's. Our first

meeting had better be there, so before then please—”

He bowed and went out. As he passed the library door

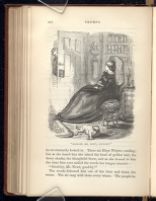

[ILLUSTRATION]

"Good-by, Mr. Newt, Good-by!"

[Description: 538EAF. Page 412. In-line Illustration. Image of a woman sitting reclined in a chair with a book in her lap. She and the little dog at her feet are both looking at a man who has poked his head into the room.]

he involuntarily looked in. There sat Hope Wayne, reading;

but as she heard him she raised the head of golden hair, the

dewy cheeks, the thoughtful brow, and as she bowed to him

the clear blue eyes smiled the words her tongue uttered—

“Good-by, Mr. Newt, good-by!”

The words followed him out of the door and down the

street. The air rang with them every where. The people he

passed seemed to look at him as if they were repeating them.

Distant echoes caught them up and whispered them. He

heard no noise of carriages, no loud city hum; he only heard,

fainter and fainter, softer and softer, sadder and sadder, and

ever following on, “Good-by, Mr. Newt, good-by!”