36. CHAPTER XXXVI.

THE BACK WINDOW.

Lawrence Newt was not unmindful of the difference of

age between Amy Waring and himself; and instinctively he

did nothing which could show to others that he felt more for

her than for a friend. Younger men, who could not help

yielding to the charm of her presence, never complained of

him. He was never “that infernal old bore, Lawrence Newt,”

to them. More than one of them, in the ardor of young feeling,

had confided his passion to Lawrence, who said to him,

bravely, “My dear fellow, I do not wonder you feel so. God

speed you—and so will I, all I can.”

And he did so. He mentioned the candidate kindly to

Miss Waring. He repeated little anecdotes that he had heard

to his advantage. Lawrence regarded the poor suitor as a

painter does a picture. He took him up in the arms of his

charity and moved him round and round. He put him upon

his sympathy as upon an easel, and turned on the kindly lights

and judiciously darkened the apartment.

His generosity was chivalric, but it was unavailing. Beautiful

flowers arrived from the aspiring youths. They were so

lovely, so fragrant! What taste that young Hal Battlebury

has! remarks Lawrence Newt, admiringly, as he smells the

flowers that stand in a pretty vase upon the centre-table. Amy

Waring smiles, and says that it is Thorburn's taste, of whom

Mr. Battlebury buys the flowers. Mr. Newt replies that it is

at least very thoughtful in him. A young lady can not but

feel kindly, surely, toward young men who express their good

feeling in the form of flowers. Then he dexterously leads the

conversation into some other channel. He will not harm the

cause of poor Mr. Battlebury by persisting in speaking of him

and his bouquets, when that persistence will evidently render

the subject a little tedious.

Poor Mr. Hal Battlebury, who, could he only survey the Waring

mansion from the lower floor to the roof, would behold his

handsome flowers that came on Wednesday withering in cold

ceremony upon the parlor-table—and in Amy Waring's bureau-drawer

would see the little book she received from “her

friend Lawrence Newt” treasured like a priceless pearl, with

a pressed rose laid upon the leaf where her name and his are

written—a rose which Lawrence Newt playfully stole one

evening from one of the ceremonious bouquets pining under

its polite reception, and said gayly, as he took leave, “Let this

keep my memory fragrant till I return.”

But it was a singular fact that when one of those baskets

without a card arrived at the house, it was not left in superb

solitary state upon the centre-table in the parlor, but bloomed

as long as care could coax it in the strict seclusion of Miss

Waring's own chamber, and then some choicest flower was

selected to be pressed and preserved somewhere in the depths

of the bureau.

Could the bureau drawers give up their treasures, would

any human being longer seem to be cold? would any maiden

young or old appear a voluntary spinster, or any unmarried

octogenarian at heart a bachelor?

For many a long hour Lawrence Newt stood at the window

of the loft in the rear of his office, and looked up at the window

where he had seen Amy Waring that summer morning.

He was certainly quite as curious about that room as Hope

about his early knowledge of her home.

“I'll just run round and settle this matter,” said the merchant

to himself.

But he did not stir. His hands were in his pockets. He

was standing as firmly in one spot as if he had taken root,

“Yes—upon the whole, I'll just run round,” thought Lawrence,

without the remotest approach to motion of any kind.

But his fancy was running round all the time, and the fancies

of men who watch windows, as Lawrence Newt watched this

window, are strangely fantastic. He imagined every thing in

that room. It was a woman with innumerable children, of

course—some old nurse of Amy's—who had a kind of respectability

to preserve, which intrusion would injure. No, no,

by Heaven! it was Mrs. Tom Witchet, old Van Boozenberg's

daughter! Of course it was. An old friend of Amy's, half-starving

in that miserable lodging, and Amy her guardian angel.

Lawrence Newt mentally vowed that Mrs. Tom Witchet

should never want any thing. He would speak to Amy at

the next meeting of the Round Table.

Or there were other strange fancies. What will not an

India merchant dream as he gazes from his window? It was

some old teacher of Amy's—some music-master, some French

teacher—dying alone and in poverty, or with a large family.

No, upon the whole, thought Lawrence Newt, he's not old

enough to have a large family—he is not married—he has too

delicate a nature to struggle with the world—he was a gentleman

in his own country; and he has, of course, it's only natural—how

could he possibly help it?—he has fallen in love with

Miss Waring. These music-masters and Italian teachers are

such silly fellows. I know all about it, thought Mr. Newt;

and now he lies there forlorn, but picturesque and very handsome,

singing sweetly to his guitar, and reciting Petrarch's

sonnets with large, melancholy eyes. His manners refined

and fascinating. His age? About thirty. Poor Amy! Of

course common humanity requires her to come and see that

he does not suffer. Of course he is desperately in love, and

she can only pity. Pity? pity? Who says something about

the kinship of pity? I really think, says Lawrence Newt to

himself, that I ought to go over and help that unfortunate

young man. Perhaps he wishes to return to his native

country. I am sure he ought to. His native air will be

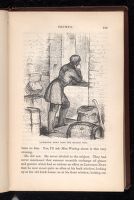

[ILLUSTRATION]

Lawernce Newt Sees The Reason Why.

[Description: 538EAF. Page 219. In-line Illustration. Image of a man looking out of a window. His back is to the reader. He is leaning on one elbow and is resting his chin in his hand.]

balm to him. Yes, I'll ask Miss Waring about it this very

evening.

He did not. He never alluded to the subject. They had

never mentioned that summer noontide exchange of glance

and gesture which had so curious an effect on Lawrence Newt

that he now stood quite as often at his back window, looking

up at the old brick house, as at his front window, looking out

over the river and the ships, and counting the spires—at least

it seemed so—in Brooklyn.

For how could Lawrence know of the book that was kept

in the burean drawer—of the rose whose benediction lay forever

fragrant upon those united names?

“I am really sorry for Hal Battlebury,” said the merchant

to himself. “He is such a good, noble fellow! I should

have supposed that Miss Waring would have been so very

happy with him. He is so suitable in every way; in age,

in figure, in tastes—in sympathy altogether. Then he is so

manly and modest, so simple and true. It is really very—

very—”

And so he mused, and asked and answered, and thought of

Hal Battlebury and Amy Waring together.

It seemed to him that if he were a younger man—about the

age of Battlebury, say—full of hope, and faith, and earnest endeavor—a

glowing and generous youth—it would be the very

thing he should do—to fall in love with Amy Waring. How

could any man see her and not love her? His reflections

grew dreamy at this point.

“If so lovely a girl did not return the affection of such a

young man, it would be—of course, what else could it be?—it

would be because she had deliberately made up her mind that,

under no conceivable circumstances whatsoever, would she

ever marry.”

As he reached this satisfactory conclusion Lawrence Newt

paced up and down before the window, with his hands still

buried in his pockets, thinking of Hal Battlebury—thinking

of the foreign youth with the large, melancholy eyes pining

upon a bed of pain, and reciting Petrarch's sonnets, in the

miserable room opposite—thinking also of that strange coldness

of virgin hearts which not the ardors of youth and love

could melt.

And, stopping before the window, he thought of his own

boyhood—of the first wild passion of his young heart—of the

little hand he held—of the soft darkness of eyes whose light

mingled with his own—again the palm-trees—the rushing

river—when, at the very window upon which he was unconsciously

gazing, one afternoon a face appeared, with a black

silk handkerchief twisted about the head, and looking down

into the court between the houses.

Lawrence Newt stared at it without moving. Both windows

were closed, nor was the woman at the other looking

toward him. He had, indeed, scarcely seen her fully before

she turned away. But he had recognized that face. He had

seen a woman he had so long thought dead. In a moment

Amy Waring's visit was explained, and a more heavenly light

shone upon her character as he thought of her.

“God bless you, Amy dear!” were the words that unconsciously

stole to his lips; and going into the office, Lawrence

Newt told Thomas Tray that he should not return that afternoon,

wished his clerks good-day, and hurried around the corner

into Front Street.