Trumps a novel |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. | CHAPTER VII.

CASTLE DANGEROUS. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| 62. |

| 63. |

| 64. |

| 65. |

| 66. |

| 67. |

| 68. |

| 69. |

| 70. |

| 71. |

| 72. |

| 73. |

| 74. |

| 75. |

| 76. |

| 77. |

| 78. |

| 79. |

| 80. |

| 81. |

| 82. |

| 83. |

| 84. |

| 85. |

| 86. |

| 87. |

| 88. |

| 89. |

| 90. |

| CHAPTER VII.

CASTLE DANGEROUS. Trumps | ||

7. CHAPTER VII.

CASTLE DANGEROUS.

The next day when school was dismissed, Abel asked leave

to stroll out of bounds. He pushed along the road, whistling

cheerily, whipping the road-side grass and weeds with his little

ratan, and all the while approaching the foot of the hill up

which the road wound through the estate of Pinewood. As

he turned up the hill he walked more slowly, and presently

stopped and leaned upon a pair of bars which guarded the entrance

of one of Mr. Burt's pastures. He gazed for some time

down into the rich green field that sloped away from the road

toward a little bowery stream, but still whistled, as if he were

looking into his mind rather than at the landscape.

After leaning and musing and vaguely whistling, he turned

up the hill again and continued his walk.

At length he reached the entrance of Pinewood—a high iron

gate, between huge stone posts, on the tops of which were

urns overflowing with vines, that hung down and partly tapestried

the columns. Immediately upon entering the grounds

the carriage avenue wound away from the gate, so that the

passer-by could see nothing as he looked through but the

hedge which skirted and concealed the lawn. The fence upon

the road was a high, solid stone wall, along whose top clustered

a dense shrubbery, so that, although the land rose from

the road toward the house, the lawn was entirely sequestered;

and you might sit upon it and enjoy the pleasant rural prospect

of fields, woods, and hills, without being seen from the

road. The house itself was a stately, formal mansion. Its

light color contrasted well with the lofty pine-trees around it.

But they, in turn, invested it with an air of secrecy and gloom,

unrelieved by flowers or blossoming shrubs, of which there

were no traces near the house, although in the rear there was

for flowers.

These were the pine-trees that Hope Wayne had heard sing

all her life—but sing like the ocean, not like birds or human

voices. In the black autumn midnights they struggled with

the north winds that smote them fiercely and filled the night

with uproar, while the child cowering in her bed thought of

wrecks on pitiless shores—of drowning mothers and hapless

children. Through the summer nights they sighed. But it

was not a lullaby—it was not a serenade. It was the croning

of a Norland enchantress, and young Hope sat at her open

window, looking out into the moonlight, and listening.

Abel Newt opened the gate and passed in. He walked

along the avenue, from which the lawn was still hidden by the

skirting hedge, went up the steps, and rang the bell.

“Is Mr. Burt at home?” he asked, quietly.

“This way, Sir,” said the nimble Hiram, going before, but

half turning and studying the visitor as he spoke, and quite

unable to comprehend him at a glance. “I will speak to

him.”

Abel Newt was shown into a large drawing-room. The

furniture was draped for the season in cool-colored chintz.

There was a straw matting upon the floor. The chandeliers

and candelabras were covered with muslin, and heavy muslin

curtains hung over the windows. The tables and chairs were

of a clumsy old-fashioned pattern, with feet in the form of

claws clasping balls, and a generally stiff, stately, and uncomfortable

air. The fire-place was covered by a heavy painted

fire-board. The polished brass andirons, which seemed to feel

the whole weight of responsibility in supporting the family

dignity, stood across the hearth, belligerently bright, and there

were sprays of asparagus in a china vase in front of them.

A few pictures hung upon the wall—family portraits, Abel

thought; at least old Christopher was there, painted at the

age of ten, standing in very clean attire, holding a book in

one hand and a hoop in the other. The picture was amusing,

equally devoted to study and play. That singular sneering

smile flitted over his face as he muttered, “The Reverend

Gabriel Bennet!”

There were a few books upon the centre-table, carefully

placed and balanced as if they had been porcelain ornaments.

The bindings and the edges of the leaves had a fresh, unworn

look. The outer window-blinds were closed, and the whole

room had a chilly formality and dimness which was not hospitable

nor by any means inspiring.

Abel seated himself in an easy-chair, and was still smiling

at the portrait of Master Christopher Burt at the age of ten,

when that gentleman, at the age of seventy-three, was heard

in the hall. Hiram had left the door open, so that Abel had

full notice of his approach, and rose just before the old gentleman

entered, and stood with his cap in his hand and his

head slightly bent.

Old Burt came into the room, and said, a little fiercely, as

he saw the visitor,

“Well, Sir!”

Abel bowed.

“Well, Sir!” he repeated, more blandly, apparently mollified

by something in the appearance of the youth.

“Mr. Burt,” said Abel, “I am sure you will excuse me when

you understand the object of my call; although I am fully

aware of the liberty I am taking in intruding upon your valuable

time and the many important cares which must occupy

the attention of a gentleman so universally known, honored,

and loved in the community as you are, Sir.”

“Did you come here to compliment me, Sir?” asked Mr.

Burt. “You've got some kind of subscription paper, I suppose.”

The old gentleman began to warm up as he thought

of it. “But I can't give any thing. I never do—I never

will. It's an infernal swindle. Some deuced Missionary Society,

or Tract Society, or Bible Society, some damnable doing-good

society, that bleeds the entire community, has sent you

They're always at it. They're always sending boys, and ministers

in the milk, by Jove! and women that talk in a way to

turn the milk sour in the cellar, Sir, and who have already

turned themselves sour in the face, Sir, and whom a man can't

turn out of doors, Sir, to swindle money out of innocent people!

I tell you, young man, 'twon't work! I'll be whipped

if I give you a solitary red cent!” And Christopher Burt, in

a fine wrath, seated himself by the table and wiped his forehead.

Abel stood patiently and meekly under this gust of fury,

and when it was ended, and Mr. Burt was a little composed,

he began quietly, as if the indignation were the most natural

thing in the world:

“No, Sir; it is not a subscription paper—”

“Not a subscription paper!” interrupted the old gentleman,

lifting his head and staring at him. “Why, what the deuce

is it, then?”

“Why, Sir, as I was just saying,” calmly returned Abel,

“it is a personal matter altogether.”

“Eh! eh! what?” cried Mr. Burt, on the edge of another

paroxysm, “what the deuce does that mean? Who are you,

Sir?”

“I am one of Mr. Gray's boys, Sir,” replied Abel.

“What! what!” thundered Grandpa Burt, springing up

suddenly, his mind opening upon a fresh scent. “One of Mr.

Gray's boys? How dare you, Sir, come into my house?

Who sent you here, Sir? What right have you to intrude

into this place, Sir? Hiram! Hiram!”

“Yes, Sir,” answered the man, as he came across the hall.

“Show this young man out.”

“He may have some message, Sir,” said Hiram, who had

heard the preceding conversation.

“Have you got any message?” asked Mr. Burt.

“No, Sir; but I—”

“Then why, in Heaven's name, don't you go?”

“Mr. Burt,” said Abel, with placid persistence, “being one

of Mr. Gray's boys, I go of course to Dr. Peewee's Church,

and there I have so often seen—”

“Come, come, Sir, this is a little too much. Hiram, put

this boy out,” said the old gentleman, quite beside himself as

he thought of his grand-daughter. “Seen, indeed! What

business have you to see, Sir?”

“So often seen your venerable figure,” resumed Abel in the

same tone as before, while Mr. Burt turned suddenly and

looked at him closely, “that I naturally asked who you were.

I was told, Sir; and hearing of your wealth and old family,

and so on, Sir, I was interested—it was only natural, Sir—in

all that belongs to you.”

“Eh! eh! what?” said Mr. Burt, quickly.

“Particularly, Mr. Burt, in your—”

“By Jove! young man, you'd better go if you don't want

to have your head broken. D'ye come here to beard me in

my own house? By George! your impudence stupefies me,

Sir. I tell you go this minute!”

But Abel continued:

“In your beautiful—”

“Don't dare to say it, Sir!” cried the old man, shaking his

finger.

“Place,” said Abel, quietly.

The old gentleman glared at him with a look of mixed surprise

and suspicion. But the boy wore the same look of candor.

He held his cap in his hand. His black hair fell around

his handsome face. He was entirely calm, and behaved in the

most respectful manner.

“What do you mean, Sir?” said Christopher Burt, in great

perplexity, as he seated himself again, and drew a long breath.

“Simply, Sir, that I am very fond of sketching. My teacher

says I draw very well, and I have had a great desire to

draw your place, but I did not dare to ask permission. It is

said in school, Sir, that you don't like Mr. Gray's boys, and I

knew nobody who could introduce me. But to-day, as I came

could make a pretty picture if I could only get leave to come

inside the grounds, that almost unconsciously I found myself

coming up the avenue and ringing the bell. That's all, Sir;

and I'm sure I beg your pardon for troubling you so much.”

Mr. Burt listened to this speech with a pacified air. He

was perhaps a little ashamed of his furious onslaughts and interruptions,

and therefore the more graciously inclined toward

the request of the young man.

So the old man said, with tolerable grace,

“Well, Sir, I am willing you should draw my house. Will

you do it this afternoon?”

“Really, Sir,” replied Abel, “I had no intention of asking

you to-day; and as I strolled out merely for a walk, I did not

bring my drawing materials with me. But if you would allow

me to come at any time, Sir, I should be very deeply

obliged. I am devoted to my art, Sir.”

“Oh! you mean to be an artist?”

“Perhaps, Sir.”

“Phit! phit! Don't do any such silly thing, Sir. An artist!

Why how much does an artist make in a year?”

“Well, Sir, the money I don't know about, but the fame!”

“Oh! the fame! The fiddle, Sir! You are capable of better

things.”

“For instance, Mr. Burt—”

“Trade, Sir, trade—trade. That is the way to fortune in

this country. Enterprise, activity, shrewdness, industry, that's

what a young man wants. Get rid of your fol-de-rol notions

about art. Benjamin West was a great man, Sir; but he was

an exception, and besides he lived in England. I respect

Benjamin West, Sir, of course. We all do. He made a good

thing of it. Take the word of an old man who has seen life

and knows the world, and remember that, with all your fine

fiddling, it is money makes the mare go. Old men like me

don't mince matters, Sir. It's money—money!”

Abel thought old men sometimes minced grammar a little,

“Yes, Sir.”

“About drawing the house, come when you choose,” said

Mr. Burt, rising.

“It may take more than one, or even three or four afternoons,

Sir, to do it properly.”

“Well, well. If I'm not at home ask for Mrs. Simcoe, d'ye

hear? Mrs. Simcoe. She will attend to you.”

Abel bowed very respectfully and as if he were controlling

a strong desire to kneel and kiss the foot of his Holiness, Christopher

Burt, but he mastered himself, and Hiram opened the

front door.

“Good-by, Hiram,” said Abel, putting a piece of money into

his hand.

“Oh, no, Sir,” said Hiram, pocketing the coin.

Abel walked sedately down the steps, and looked carefully

around him. He scanned the windows; he glanced under the

trees; but he saw nothing. He did every thing, in fact, but

study the house which he had been asking permission to draw.

He looked as if for something or somebody who did not appear.

But as Hiram still stood watching him, he moved

away.

He walked faster as he approached the gate. He opened

it; flung it to behind him, broke into a little trot, and almost

tumbled over Gabriel Bennet and Little Malacca as he did so.

The collision was rude, and the three boys stopped.

“You'd better look where you're going,” said Gabriel,

sharply, his cheeks reddening and swelling.

Abel's first impulse was to strike; but he restrained himself,

and in the most contemptuous way said merely,

“Ah, the Reverend Gabriel Bennet!”

He had scarcely spoken when Gabriel fell upon him like a

young lion. So sudden and impetuous was his attack that for

a moment Abel was confounded. He gave way a little, and

was well battered almost before he could strike in return.

Then his strong arms began to tell. He was confident of victory,

The Battle.

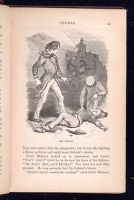

[Description: 538EAF. Page 043. In-line Illustration. Image of three young men and a coach with two horses. The men are in the foreground of the image. One is standing with his fists clenched, the second is sprawled on the ground with his eyes closed, and the third kneels over the man on the ground. The coach with horses and a driver are in the background, and they appear to be bearing down on the group in the foreground.] and calmer than his antagonist; but it was like fightinga flame, so fierce and rapid were Gabriel's strokes.

Little Malacca looked on in amazement and terror.

“Don't! don't!” cried he, as he saw the faces of the fighters.

“Oh, don't! Abel, you'll kill him!” For Abel was now fully

aroused. He was seriously hurt by Gabriel's blows.

“Don't! there's somebody coming!” cried Little Malacca,

driving down the hill.

The combatants said nothing. The faces of both of them

were bruised, and the blood was flowing. Gabriel was clearly

flagging; and Abel's face was furious as he struck his heavy

blows, under which the smaller boy staggered, but did not

yet succumb.

“Oh, please! please!” cried Little Malacca, imploringly, the

tears streaming down his face.

At that moment Abel Newt drew back, aimed a tremendous

blow at Gabriel, and delivered it with fearful force upon his

head. The smaller boy staggered, reeled, threw up his arms,

and fell heavily forward into the road, senseless.

“You've killed him! You've killed him!” sobbed Little

Malacca, piteously, kneeling down and bending over Gabriel.

Abel Newt stood bareheaded, frowning under his heavy

hair, his hands clenched, his face bruised and bleeding, his

mouth sternly set as he looked down upon his opponent. Suddenly

he heard a sound close by him—a half-smothered cry.

He looked up. It was the Burt carriage, and Hope Wayne

was gazing in terror from the window.

| CHAPTER VII.

CASTLE DANGEROUS. Trumps | ||