| Mark Twain's sketches, new and old | ||

98

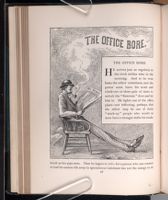

THE OFFICE BORE.

HE arrives just as regularly as

the clock strikes nine in the

morning. And so he even

beats the editor sometimes, and the

porter must leave his work and

climb two or three pair of stairs to

unlock the “Sanctum” door and let

him in. He lights one of the office

pipes—not reflecting, perhaps, that

the editor may be one of those

“stuck-up” people who would as

soon have a stranger defile his toothbrush

as his pipe-stem. Then he begins to loll—for a person who can consent

to loaf his useless life away in ignominious indolence has not the energy to sit

99

then gets into a chair, hangs his head back and his arms abroad, and

stretches his legs till the rims of his boot-heels rest upon the floor; by and by

sits up and leans forward, with one leg or both over the arm of the chair. But

it is still observable that with all his changes of position, he never assumes the

upright or a fraudful affectation of dignity. From time to time he yawns, and

stretches, and scratches himself with a tranquil, mangy enjoyment, and now

and then he grunts a kind of stuffy, overfed grunt, which is full of animal contentment.

At rare and long intervals, however, he sighs a sigh that is the

eloquent expression of a secret confession, to wit: “I am useless and a nuisance,

a cumberer of the earth.” The bore and his comrades—for there are usually

from two to four on hand, day and night—mix into the conversation when men

come in to see the editors for a moment on business; they hold noisy talks

among themselves about politics in particular, and all other subjects in general

—even warming up, after a fashion, sometimes, and seeming to take almost a

real interest in what they are discussing. They ruthlessly call an editor

from his work with such a remark as: “Did you see this, Smith, in the

`Gazette?”' and proceed to read the paragraph while the sufferer reins in his

impatient pen and listens: they often loll and sprawl round the office hour after

hour, swapping anecdotes, and relating personal experiences to each other—

hairbreadth escapes, social encounters with distinguished men, election reminiscences,

sketches of odd characters, etc. And through all those hours they never

seem to comprehend that they are robbing the editors of their time, and the

public of journalistic excellence in next day's paper. At other times they

drowse, or dreamily pore over exchanges, or droop limp and pensive over the

chair-arms for an hour. Even this solemn silence is small respite to the editor,

for the next uncomfortable thing to having people look over his shoulders,

perhaps, is to have them sit by in silence and listen to the scratching of his pen.

If a body desires to talk private business with one of the editors, he must call

him outside, for no hint milder than blasting powder or nitro-glycerine would

be likely to move the bores out of listening distance. To have to sit and endure

the presence of a bore day after day; to feel your cheerful spirits begin to sink

as his footstep sounds on the stair, and utterly vanish away as his tiresome form

100

to feel always the fetters of his clogging presence; to long hopelessly for

one single day's privacy; to note with a shudder, by and by, that to contemplate

his funeral in fancy has ceased to soothe, to imagine him undergoing in strict

and fearful detail the tortures of the ancient Inquisition has lost its power to

satisfy the heart, and that even to wish him millions and millions and millions

of miles in Tophet is able to bring only a fitful gleam of joy; to have to endure

all this, day after day, and week after week, and month after month, is an affliction

that transcends any other that men suffer. Physical pain is pastime to it,

and hanging a pleasure excursion.

| Mark Twain's sketches, new and old | ||