| Mark Twain's sketches, new and old | ||

NIAGARA.

NIAGARA FALLS is a most enjoyable

place of resort. The hotels

are excellent, and the prices not

at all exorbitant. The opportunities for

fishing are not surpassed in the country;

in fact, they are not even equalled elsewhere.

Because, in other localities,

certain places in the streams are much

better than others; but at Niagara one

place is just as good as another, for the

reason that the fish do not bite anywhere,

and so there is no use in your walking

five miles to fish, when you can depend

on being just as unsuccessful nearer

home. The advantages of this state of

things have never heretofore been properly placed before the public.

The weather is cool in summer, and the walks and drives are all pleasant and

about a mile, and pay a small sum for the privilege of looking down from a precipice

into the narrowest part of the Niagara river. A railway “cut” through a hill

would be as comely if it had the angry river tumbling and foaming through its

bottom. You can descend a staircase here a hundred and fifty feet down, and

stand at the edge of the water. After you have done it, you will wonder why you

did it; but you will then be too late.

The guide will explain to you, in his blood-curdling way, how he saw the little

steamer, Maid of the Mist, descend the fearful rapids—how first one paddle-box

was out of sight behind the raging billows, and then the other, and at what point it

was that her smokestack toppled overboard, and where her planking began to break

and part asunder—and how she did finally live through the trip, after accomplishing

the incredible feat of travelling seventeen miles in six minutes, or six miles in

seventeen minutes, I have really forgotten which. But it was very extraordinary,

anyhow. It is worth the price of admission to hear the guide tell the story nine

times in succession to different parties, and never miss a word or alter a sentence

or a gesture.

Then you drive over the Suspension Bridge, and divide your misery between the

chances of smashing down two hundred feet into the river below, and the chances

of having the railway train overhead smashing down on to you. Either possibility

is discomforting taken by itself, but mixed together, they amount in the aggregate

to positive unhappiness.

On the Canada side you drive along the chasm between long ranks of photographers

standing guard behind their cameras, ready to make an ostentatious frontispiece

of you and your decaying ambulance, and your solemn crate with a hide on

it, which you are expected to regard in the light of a horse, and a diminished and

unimportant background of sublime Niagara; and a great many people have the

incredible effrontery or the native depravity to aid and abet this sort of crime.

Any day, in the hands of these photographers, you may see stately pictures of

papa and mamma, Johnny and Bub and Sis, or a couple of country cousins, all

smiling vacantly, and all disposed in studied and uncomfortable attitudes in their

carriage, and all looming up in their awe-inspiring imbecility before the snubbed

are the rainbows, whose voice is the thunder, whose awful front is veiled in clouds,

who was monarch here dead and forgotten ages before this hackful of small reptiles

was deemed temporarily necessary to fill a crack in the world's unnoted myriads,

and will still be monarch here ages and decades of ages after they shall have gathered

themselves to their blood relations, the other worms, and been mingled with

the unremembering dust.

There is no actual harm in making Niagara a background whereon to display

one's marvellous insignificance in a good strong light, but it requires a sort of

superhuman self-complacency to enable one to do it.

When you have examined the stupendous Horseshoe Fall till you are satisfied

you cannot improve on it, you return to America by the new Suspension Bridge,

and follow up the bank to where they exhibit the Cave of the Winds.

Here I followed instructions, and divested myself of all my clothing, and put

on a waterproof jacket and overalls. This costume is picturesque, but not beautiful.

A guide, similarly dressed, led the way down a flight of winding stairs, which

wound and wound, and still kept on winding long after the thing ceased to be a

had begun to be a pleasure. We were then

well down under the precipice, but still considerably

above the level of the river.

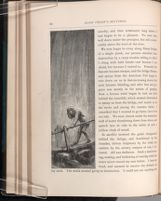

We now began to creep along flimsy bridges

of a single plank, our persons shielded from

destruction by a crazy wooden railing, to which

I clung with both hands—not because I was

afraid, but because I wanted to. Presently the

descent became steeper, and the bridge flimsier,

and sprays from the American Fall began to

rain down on us in fast-increasing sheets that

soon became blinding, and after that our progress

was mostly in the nature of groping.

Now a furious wind began to rush out from

behind the waterfall, which seemed determined

to sweep us from the bridge, and scatter us on

the rocks and among the torrents below. I

remarked that I wanted to go home; but it was

too late. We were almost under the monstrous

wall of water thundering down from above, and

speech was in vain in the midst of such a

pitiless crash of sound.

In another moment the guide disappeared

behind the deluge, and bewildered by the

thunder, driven helplessly by the wind, and

smitten by the arrowy tempest of rain, I followed.

All was darkness. Such a mad storming,

roaring, and bellowing of warring wind and

water never crazed my ears before. I bent my

head, and seemed to receive the Atlantic on

my back. The world seemed going to destruction. I could not see anything, the

of the American cataract went down my throat. If I had sprung a leak now, I

had been lost. And at this moment I discovered that the bridge had ceased, and

we must trust for a foothold to the slippery and precipitous rocks. I never was so

scared before and survived it. But we got through at last, and emerged into the

open day, where we could stand in front of the laced and frothy and seething world

of descending water, and look at it. When I saw how much of it there was, and

how fearfully in earnest it was, I was sorry I had gone behind it.

The noble Red Man has always been a friend and darling of mine. I love to

read about him in tales and legends and romances. I love to read of his inspired

sagacity, and his love of the wild free life of mountain and forest, and his general

nobility of character, and his stately metaphorical manner of speech, and his

chivalrous love for the dusky maiden, and the picturesque pomp of his dress and

accoutrements. Especially the picturesque pomp of his dress and accoutrements.

When I found the shops at Niagara Falls full of dainty Indian bead-work, and

stunning moccasins, and equally stunning toy figures representing human beings who

carried their weapons in holes bored through their arms and bodies, and had feet

shaped like a pie, I was filled with emotion. I knew that now, at last, I was going

to come face to face with the noble Red Man.

A lady clerk in a shop told me, indeed, that all her grand array of curiosities

were made by the Indians, and that they were plenty about the Falls, and that they

were friendly, and it would not be dangerous to speak to them. And sure enough,

as I approached the bridge leading over to Luna Island, I came upon a noble Son

of the Forest sitting under a tree, diligently at work on a bead reticule. He wore

a slouch hat and brogans, and had a short black pipe in his mouth. Thus does

the baneful contact with our effeminate civilization dilute the picturesque pomp

which is so natural to the Indian when far removed from us in his native haunts.

I addressed the relic as follows:—

“Is the Wawhoo-Wang-Wang of the Whack-a-Whack happy? Does the great

Speckled Thunder sigh for the war path, or is his heart contented with dreaming

of the dusky maiden, the Pride of the Forest? Does the mighty Sachem yearn to

drink the blood of his enemies, or is he satisfied to make bead reticules for the

ruin, speak!”

The relic said—

“An' is it mesilf, Dennis Hooligan, that ye'd be takin' for a dirty Injin, ye

drawlin', lantern-jawed, spider-legged divil! By the piper that played before

Moses, I'll ate ye!”

I went away from there.

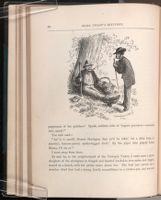

By and by, in the neighborhood of the Terrapin Tower, I came upon a gentle

daughter of the aborigines in fringed and beaded buckskin moccasins and leggins,

seated on a bench, with her pretty wares about her. She had just carved out a

wooden chief that had a strong family resemblance to a clothes-pin, and was now

and then addressed her:

“Is the heart of the forest maiden heavy? Is the Laughing Tadpole lonely?

Does she mourn over the extinguished council-fires of her race, and the vanished

glory of her ancestors? Or does her sad spirit wander afar toward the hunting-grounds

whither her brave Gobbler-of-the-Lightnings is gone? Why is my daughter

silent? Has she aught against the

paleface stranger?”

The maiden said—

“Faix, an' is it Biddy Malone ye

dare to be callin' names? Lave this,

or I'll shy your lean carcass over

the cataract, ye sniveling blaggard!”

I adjourned from there also.

“Confound these Indians!” I said.

“They told me they were tame; but,

if appearances go for anything, I

should say they were all on the war

path.”

I made one more attempt to fraternize

with them, and only one. I

came upon a camp of them gathered

in the shade of a great tree, making wampum and moccasins, and addressed them

in the language of friendship:

“Noble Red Men, Braves, Grand Sachems, War Chiefs, Squaws, and High Muck-a-Mucks,

the paleface from the land of the setting sun greets you! You, Beneficent

Polecat—you, Devourer of Mountains—you, Roaring Thundergust—you, Bully Boy

with a Glass eye—the paleface from beyond the great waters greets you all! War

and pestilence have thinned your ranks, and destroyed your once proud nation.

Poker and seven-up, and a vain modern expense for soap, unknown to your glorious

ancestors, have depleted your purses. Appropriating, in your simplicity, the property

of others, has gotten you into trouble. Misrepresenting facts, in your simple

forty-rod whisky, to enable you to get drunk and happy and tomahawk your families,

has played the everlasting mischief with the picturesque pomp of your dress, and

here you are, in the broad light of the nineteenth century, gotten up like the ragtag

and bobtail of the purlieus of New York. For shame! Remember your ancestors!

Recall their mighty deeds! Remember Uncas!—and Red Jacket!—and Hole in

the Day!—and Whoopdedoodledo! Emulate their achievements! Unfurl yourselves

under my banner, noble savages, illustrious guttersnipes”—

“Down wid him!” “Scoop the blaggard!” “Burn him!” “Hang him!”

“Dhround him!”

It was the quickest operation that ever was. I simply saw a sudden flash in the

air of clubs, brickbats, fists, bead-baskets, and moccasins—a single flash, and they

all appeared to hit me at once, and no two of them in the same place. In the next

instant the entire tribe was upon me. They tore half the clothes off me; they

broke my arms and legs; they gave me a thump that dented the top of my head

till it would hold coffee like a saucer; and, to crown their disgraceful proceedings

and add insult to injury, they threw me over the Niagara Falls, and I got wet.

About ninety or a hundred feet from the top, the remains of my vest caught on

a projecting rock, and I was almost drowned before I could get loose. I finally

fell, and brought up in a world of white foam at the foot of the Fall, whose celled

and bubbly masses towered up several inches above my head. Of course I got

into the eddy. I sailed round and round in it forty-four times—chasing a chip

and gaining on it—each round trip a half mile—reaching for the same bush on the

bank forty-four times, and just exactly missing it by a hair's-breadth every time.

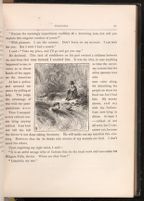

At last a man walked down and sat down close to that bush, and put a pipe in

his mouth, and lit a match, and followed me with one eye and kept the other on

the match, while he sheltered it in his hands from the wind. Presently a puff of

wind blew it out. The next time I swept around he said—

“Got a match?”

“Yes; in my other vest. Help me out, please.”

“Not for Joe.”

When I came round again, I said—

“Excuse the seemingly impertinent curiosity of a drowning man, but will you

explain this singular conduct of yours?”

“With pleasure. I am the coroner. Don't hurry on my account. I can wait

for you. But I wish I had a match.”

I said—“Take my place, and I'll go and get you one.”

He declined. This lack of confidence on his part created a coldness between

us, and from that time forward I avoided him. It was my idea, in case anything

happened to me, to so time the occurrence

as to throw my custom into the

hands of the opposition coroner over

on the American side.

At last a policeman came along,

and arrested me for disturbing the

peace by yelling at people on shore for

help. The judge fined me, but I had

the advantage of him. My money

was with my pantaloons, and my

pantaloons were with the Indians.

Thus I escaped. I am now lying in

a very critical condition. At least I

am lying anyway — critical or not

critical. I am hurt all over, but I cannot

tell the full extent yet, because

the doctor is not done taking inventory. He will make out my manifest this evening.

However, thus far he thinks only sixteen of my wounds are fatal. I don't

mind the others.

Upon regaining my right mind, I said—

“It is an awful savage tribe of Indians that do the bead work and moccasins for

Niagara Falls, doctor. Where are they from?”

“Limerick, my son.”

| Mark Twain's sketches, new and old | ||