The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. | I.13.8 |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I.13.8

KITCHEN FOR SERFS AND WORKMEN

The ensemble of buildings shown on the Plan of St. Gall

includes no fewer than six kitchens: the Monks' Kitchen[295]

(drawn with all of its furnishings), the Abbot's Kitchen,[296]

the Kitchen for the Novices,[297]

the Kitchen for the Sick,[298]

the Kitchen for the Distinguished Guests,[299]

and the

Kitchen for the Pilgrims and Paupers.[300]

In view of the

meticulous attention given to the need for all of these

installations, we are surprised to note the absence of a

kitchen and dining hall for laymen. The aggregate number

of serfs, workmen, and servants living within the monastic

enclosure, as a rule, exceeded that of the monks.[301]

Where

did they eat? Clearly, not in the Refectory. This would be

impossible not only because there is no entrance into the

Refectory for the serfs and servants; but also because a

regulation of the Second Synod of Aachen (817) prescribes

"that laymen should not be conducted into the refectory

for the sake of eating and drinking" (Ut laici causa manducandi

uel bibendi in refectorium non ducantur).[302]

Emil Lesne's contention[303]

that the meals of the servants

were not prepared in the Monks' Kitchen is right, in my

opinion, if for no other reason than because of the differences

PLAN OF ST. GALL

WHAT SCHEME OF WATERWAYS?

The Plan invites speculation concerning the water supply for the needs of the monastic

population and the removal, beyond the confines of the site, of wastes and waters polluted

by man and beast. The Plan does illustrate, as a paradigmatic concept, the composition

of structures. But what conditions, topographic, hydrographic, climatic (winds, snow,

rain) governed considerations for site selection?

Essential to the operation and good health of the monastery were good drainage, an

adequate supply of potable water, and a well-functioning scheme of sanitation, all

conditions related to the type of terrain. The site illustrated in figure 53 is entirely

assumptive. Contours provide downslope to the south: a downslope to the west of

about 15 feet in the length of the Plan is shown, (roughly 0.25 inch per foot, or 25

inches per 100 feet). That of 83 privies shown on the Plan, 74 are on or near the

north and east boundaries, may or may not allude to planning for odors as related

to prevailing winds, or to a system by which, for most of the privies, excreta could

be removed by water-carriage for building sites on terrains where generous slope and

abundant water supply existed.

Besides solid wastes, sewage comprises water fouled from baths, kitchen use, lavatories,

and also surface drainage from rain or snow. These fluid wastes may have been

removed by surface channels, or by subsurface conduits, probably of terra cotta made

with nesting joints (such as present day "bell and spigot" clay pipe). Drinking

water is best distributed by conduit with tight or sealed joints to prevent leakage and

contamination from without. These two waterways, supply and waste, must be

distinct and separate at all points through their full length.

Bronze and lead, and sometimes wood, were used for piping by the Romans. Delivery

of drinking water by horse drawn tank or barrel was possible. Probably all of these

materials and modes of water supply and disposal of sewage were in use for a

monastery of the period and, no doubt, varied according to the availability of materials,

the skill of local craftsmen and the level of technology of the region.

On sites where no water was available for sluicing of sewage, surface or underground,

excreta was probably disposed in pits or middens, and treated with ashes or floor dust

and sweepings, then removed at intervals and applied as manure on neighboring

ground. From the agricultural view this was sound practice; from the view of hygiene,

not to be tolerated. Nevertheless, such practice existed and exists today in some

communities.

While the 50 privies along the north boundary suggest planning for a system of

sewage removal, the mills and mortars on the south boundary imply the presence of

a running stream as a power source for their operation.

It is notable that only those buildings of the Plan designated for occupancy by clerics

or by men of noble status are provided with privies. The various buildings for essential

services to the monastery, including services requiring high expertise (cooking, beer

and wine making, goldsmithing, etc) have no privies. These men, about 70 percent

of the monastery population, made shift for themselves according to the customs of

the time and the regulations of the establishment.

The nine privies in Building 4, the Monks' Toilets (adjacent to Building 3, the

Monks' Dormitory) attached to the core of the Plan, pose a problem for sewage

removal. A surface sewage ditch does not seem likely here in the midst of clean

water lines; removal from this central location in underground conduit by water

would be no small feat even if feasible. The proximity of these privies to the Monks'

Vegetable Garden X and the Monks' Orchard Y may indicate that an agricultural

destination for human wastes produced in Building 4 was intended.

Figure 53 suggests how, within the scheme of topography shown, supply lines could

penetrate the east boundary of the site. Interior branches we do not show.

The Plan of St. Gall, by the careful ordering of its structures, could adapt well

to an engineered system of water supply and waste drainage consonant with the state

of the art of the plumber and the sanitary knowledge of the time.

E. B.

SCALE: ⅛ ORIGINAL SIZE (1:1536)

to eat meat; the servants were not.[304] To provide two

completely different menus in a kitchen not more than 30

feet square for about 300 people[305] would not have been

feasible.

The 370 pigs that the monastery of Corbie hung in its

larder annually were for the serfs, the guests, and the sick.[306]

Abbot Wala of Corbie (826-833), in his list of monastic

officials, mentions a cellerarius familiae, i.e., a cellarer for

the laymen, who is subordinate to the prior, and provides

the monastery's servants with their drink.[307]

Hildemar (845850)

in his commentary to the Rule of St. Benedict refers

to a monk whose special task was to take care of the serfs'

needs for food and drink.[308]

Yet nowhere in the vast body

of Carolingian consuetudinaries, or for that matter in any

other contemporaneous sources as far as I know,[309]

is there

any evidence for the existence of a kitchen for laymen.

The Plan of St. Gall, I believe, enables us to solve this

puzzle. It suggests that the meals of the serfs and the

servants were cooked in their own houses, which differ

from those of the monks in that they were furnished with

hearths and in this way equipped for the cooking of meals.[310]

The serfs apparently continued within the monastic enclosure

to eat as they had before they entered the monastery's

service and to live in the same kind of houses.

Had the serfs and workmen eaten at a common table,

their considerable number would have required the monastery

to have been provided with a dining hall and kitchen

even larger than that provided for the monks. The absence

of such structures on the Plan cannot be interpreted as an

oversight or omission, because presumably the dining

arrangements were handled in quite a different way.

It would nevertheless be unreasonable to assume that

every layman cooked his own meals. In fact, this was probably

not even done by every group of servants living

together in a given house. It is more logical to assume that

the meals for the lay servants were prepared and eaten in

two or three of the larger service structures strategically

located so as to accommodate people living in different

parts of the enclosure. I feel this view is supported by an

unusual arrangement in the House for Horses and Oxen

and Their Keepers.[311]

This house is provided with a large

central hall with benches all around its walls, offering sitting

space for forty-three people (fig. 54). The hearth is three

times as large as the hearths in the other houses and

has inscribed into it an

might well stand for the kind of boom or rigging that in the

Middle Ages was used to hang pots over open fires. It is

here, in my opinion, that the meals were cooked and eaten

by all the serfs and herdsmen who lived west of the Great

Collective Workshop.[312]

The latter house, too, may have

served a similar purpose. It is occupied by men of higher

skills and its yard is separated from that of the herdsmen

by a conspicuous fence. A third center of this kind may

have existed in the area of the gardeners and the fowl-keepers.[313]

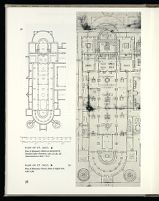

54. PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN (BUILDING 33, SEE PLAN PAGE XXIV)

The hall of this building (DOMUS BUBULCORUM ET EQUOS SERUANTIUM) may have served as kitchen and dining space for herdsmen of this

and other houses. Its unusually large hearth, and benches ranging around the walls, offering seating for over forty people, appear to attest

communal use of this space.

56. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Plan of Monastery Church as interpreted by

Ostendorf [after Ostendorf, 1922, 42, fig. 53]

(Illustrated above at about 1:600)

55. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Plan of Monastery Church, shown ½ original size,

scale 1:384

Dr. Joseph Semmler, too, with whom I have had the pleasure of

corresponding about this matter, is not aware of the existence of any

other documentary sources that would throw further light on this

question. Chapter 26 of the first synod of Aachen (816) prescribes: "Ut

seruitores non ad unam mensam sed in propriis locis post refectionum fratrum

reficiant quibus eadem lectio quae fratribus recitata est recitatur" (Synodi

primae decr. auth., chap. 26; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 465).

One might feel tempted to interpret this directive as referring to the

serfs and workmen, as Emile Lesne has done (op. cit., 194), but the

servitores mentioned in this resolution are not the monastery's lay

servants, but the "servers" (servitores or hebdomadarii) who are chosen

from among the monks for a weekly term of kitchen duty (see below, p.

279f.). A proper translation of this chapter would read: "That the

servers take their meal, not at one table, but each at his proper place [i.e.,

the place in the Refectory assigned to him according to the date of his

entry into monastic life] after the brothers have eaten, and that they be

given the same reading as was given to them." It is in this sense that the

passage was interpreted by Semmler, 1963, 44.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||