The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. | I. 13 |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I. 13

OMISSIONS AND OVERSIGHTS

I.13.1

INTENT OR INADVERTENCY

It would be incongruous to expect that a plan comprising

forty buildings and other installations, such as a cemetery

and gardens, would be free of omissions or oversights. A

few of these do indeed exist, but for absolute errors one

looks in vain. The majority of missing features, which

might appropriately be termed omissions, appear, however,

to have been left out by intent rather than by neglect or

inadvertence.

Most conspicuous among these are: the lack of consistent

attention to stairs and privies; the absence of any suggestion

of waterways to operate the monastery's water-driven

machinery and to dispose of the monastery's waste; and,

perhaps, the absence of a peripheral wall enclosure.

I.13.2

STAIRS

The traditional assertion that "stairs are omitted altogether"

on the Plan[262]

is incorrect. Where stairs are vital to the

liturgical service or are of an extraordinary construction,

they are delineated with the greatest care. Two flights of

seven steps (septem gradus, similiter) lead from the crossing

of the Church to the forechoir (fig. 99). The altars in the

transept rise from platforms that are raised by two steps

over the pavement of the transept arms (fig. 99). The apse

of St. Peter at the western end of the church is raised by

one step over the contiguous pavement of the nave (fig.

84); the same condition is found in the two apses of the

church of the novices and the sick. Finally, the altars of St.

Michael and St. Gabriel at the top of the two circular

towers are made accessible by a circular stair, the winding

course of which is delineated by meticulously drawn spirals

(fig. 84).

On the other hand, one observes with some surprise that

the large double-storied buildings of the monks, which

surround the cloister, contain not the slightest suggestion

of stairs. We do not know at which point and by what

means the monks entered the Vestiary, above the Refectory

(fig. 211), or the Larder, which lies above the Cellar (fig.

225). The structure which houses Dormitory (above) and

Warming Room (below) has four exits. One of them, a

passage leading to Bathhouse and Laundry, is designated by

its title as issuing from the Warming Room. The others

may refer either to ground level or upper story—or to doors

located one above the other on two levels. The Privy was

probably on Dormitory level with cesspool and running

water beneath, but might also have been accessible from

ground level by stairs connecting Warming Room and

Dormitory internally (for suggestions how this might

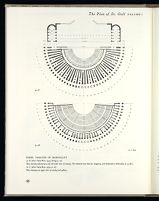

ROME. THEATER OF MARCELLUS

51.B [after Calza-Bini, 1953, facing p. 15]

Plan showing substructure and two lower tiers of seating. The memorial was built by Augustus, and dedicated to Marcellus in 13 B.C.

51.C [after Calza-Bini, 1953, p. 14]

Plan showing two upper tiers of seating and gallery.

51.A FORMA URBIS ROMAE

ROME. ANTIQUARIUM COMMUNALE DEL CELIO

51.A [after Carretoni, 1960, vol. 11, pl. XXIX]

Group of fragments (no. 13) shows the semicircular rows of seats in the Theater of Marcellus, and the vaulted ramps and stairs by which they

are made accessible, as though they were lying on the same plane, interweaving parts that in the building itself belong to several different levels.

cf. fig. 192).

Likewise, in the Abbot's House (fig. 251) we are not told

from what point and by what means the Abbot reached the

solar and other rooms located in the upper level of his

residence. These details the designing architect left to the

ingenuity of the builder—perhaps to protect the Plan from

being overloaded with particulars. It is to policy decisions

of this kind, bringing relief to areas that required minute

attention to other details, that the Plan owes its extraordinary

over-all clarity.

"Nirgends sind die Treppen verzeichnet," Reinhardt, 1952, 23. The

same idea is voiced by Leclercq, in Cabrol-Leclercq, VI:2, 1924, col. 92.

I.13.3

DOORS AND WINDOWS

The location of all exits and entrances is treated with the

greatest care, not only the opening by which each individual

structure is made accessible from the outside, but also all

the doors giving access, internally, from one room to

another. There are altogether some 290 doors shown on the

various buildings of the Plan, and only five true oversights

that I can find: two doors in the House of the Gardener

(fig. 426)[263]

and three in the Monks' Bake and Brew House

(fig. 462)[264]

are not shown.

The architect does not lavish quite the same degree of

attention on the designation of gates that give access from

court to court through enclosing fences. Here, as in the

case of the privies, he appears to discriminate between the

higher and lower levels of monastic polity. A gate in the

passage that connects the Abbot's House with the Church

(fig. 251) permits the Abbot to inspect the buildings lying

east of the Church, and at the same time admits the novices

and the sick to the Church on the days of the great religious

festivals.[265]

A gate in the fence that separates the grounds of

the House of the Physicians from those of the House for

Bloodletting insures that the physicians have free access to

the structures that come within their professional care.

Gates in appropriate places of the enclosure of the Outer

School (fig. 407) permit the headmaster to communicate

with his own quarters (addorsed to the northern aisle of the

Church) and allow the students to attend the divine services

by passing through the quarters of the visiting monks into

the northern transept of the Church.

Yet one looks in vain for gates in any of the fences that

enclose the various installations of the large service yard in

the western tract of the monastery site, with its stables and

houses for the emperor's staff. Here, again, I believe we

cannot speak of these omissions as oversights. The draftsman

was eager to make it clear that these installations

should be surrounded by walls or fences, but the builder,

as he adapted the elements to the terrain, would have to

determine exactly where these enclosures should be made

accessible by gates.

He used the same discretion in the designation of

windows. Arcaded openings are delineated with the greatest

care (Monks' Cloister, cloisters in the Infirmary and the

Novitiate, porches in the Abbot's House);[266]

and to make

unmistakably clear what he had in mind, he switched from

vertical to horizontal projection. In all other instances,

windows are omitted—with one exception, the Scriptorium

(fig. 99), where to neglect the appropriate conditions for

lighting would have had disastrous consequences.[267]

Openings

for ventilation are indicated in the Monks' Privy (fig.

497), again to stress an important functional need. Had

windows been shown in such buildings as the Dormitory,

the Refectory, and the Cellar, they would have impaired

the clarity of the internal layout of these structures. In the

majority of the other houses, windows could not even be

expected, because these houses belonged to a building type

that had no windows, as we shall show later.[268]

There are no doors to give access to the cooling room in the brewery,

the room where flour is stored in the bakery, and the room where the

dough is laid out in the bakery.

During the remaining part of the year the sick and the novices attend

service in their own chapels, cf. below, pp. 311ff.

I.13.4

FIREPLACES AND LOUVERS

The primary device for heating the guest and service

buildings of the Plan of St. Gall, as will be shown later,[269]

is

an open hearth (locus foci) located in the exact center of the

house; above it in the ridge is a lantern or louver (testu)

for the escape of smoke and for light and air. In most of the

larger houses these two devices are entered very carefully;

but in some they are omitted, most conspicuously so in the

workshops of the wheelwrights and coopers, and the workshops

of the goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and fullers. Again, I

do not think that these are oversights. Rather they stem

from the draftsman's desire to avoid endless reiteration of a

feature that had been clearly established in all of the truly

important houses of the Plan, and could, therefore, be

taken for granted, the more so in installations where fire

was needed not only for warmth, but also for professional

reasons.

I.13.5

WATERWAYS

The availability of a good water supply was a prime condition

for the proper functioning of a monastic settlement.

This was expressed in unmistakable terms by St. Benedict[270]

and can be inferred from countless later accounts of the

selection of suitable sites for new monastic settlements.

Most monasteries were built in the immediate vicinity of

a stream. When, toward the middle of the sixth century,

Cassiodorus the Senator founded the monastery of

Vivarium near his ancestral home of Scyllacium, in

Calabria, Italy, he established it on the river Pellena,

deflected its flow so that it brought drink to the brothers,

serviced the monastery's garden and mills, and filled the

ponds (vivaria) for the stocking and breeding of fish.[271]

In

like manner, during the reign of King Pepin (751-768),

when Count Wilbertus and Countess Ada searched for an

appropriate site for the new monastery of Lièssies, they

gave primary consideration to the availability of "water for

the running of the mill, the serving of the bakery, kitchen,

hermits were dependent on a good supply of water. St. Gall,

in 612, established himself with full deliberation at the side

of a pool which nature had carved beneath a waterfall of

the river Steinach, in Switzerland, and which he had found

to abound in fish. And a century later when this cell of the

Irish missionary was converted into a cenobitic monastery

by Abbot Otmar (719-759) it was—again deliberately—

erected at the side of this stream.[273] Elaborate waterworks

are known to have been installed by Sturmi (744-799) in

the monastery of Fulda to provide the brothers with drinking

water and to create the required slope for the sluices

which carried the water to the mills.[274]

In general the water required for the sustenance of the

community and the operation of its water-driven works was

diverted from this stream at the upper side of the monastery,

conveyed to the monastic workshops through a carefully

constructed system of flues, and then directed back to

the bed of the stream at a lower level, carrying with it all

of the monastery's waste. In many English abbeys of the

twelfth and thirteenth centuries, where the buildings themselves

have disappeared, the course of the waterways is now

completely exposed, and can be studied under ideal conditions.[275]

When a stream of running water was not available

nearby, the supply had to be brought in from a distant

source by means of an aqueduct.[276]

Such a system of aqueducts existed at the Canterbury

monastery and is depicted on two large sheets of parchment,

now inserted (with somewhat trimmed margins) into the

famous Canterbury Psalter of the Library of Trinity

College, Cambridge.[277]

Drawn around 1165, probably by

Wibert (d. 1167) who engineered the system, these drawings

(one of which is shown in fig. 52.A) trace the course of

the water from its source in the surrounding countryside

through five settling tanks—located in cornfields, vineyards,

and orchards—to a circular conduit house; thence,

through a passage in the city walls into the precinct of the

monastery itself. There is branches out into several separate

subterranean systems serving the monastic houses and

workshops, and finally it empties into the large sewers from

which the waste is carried into the town ditch.[278]

A literary parallel to this depiction of a medieval monastic

water system is to be found in Book II of the Vita prima

sancti Bernardi, written in 1153 by Arnold of Benneval,

who refers to the reconstruction of the monastery of Clairvaux

after St. Bernard's return from Rome in 1133 and the

construction of its waterworks as follows:

With funds abounding, workmen were gathered from outside, and

together with them the monks applied themselves to the impending

project with utmost zeal. Some cut the timbers, others squared off

the stones or constructed the walls, still others divided the river

Aube through a system of branching channels and lifted the bubbling

waters into the mills. Even the fullers, the bakers, the tanners, the

blacksmiths, and all the other craftsmen set themselves to the task

of fitting out the contrivances suited to their work, so that the

foaming river, diverted into every installation through subterranean

channels, may gush forth on its own account and rush to wherever

this is desired, until at length all the services peculiar to these offices

being rendered and the houses cleansed, the once diverted waters

may return to their original bed and restore the river to its proper

volume.[279]

The Plan of St. Gall nowhere suggests the existence of

any waterways. But it would be incorrect to infer from this

that the availability of water and its distribution throughout

the various monastic shops and houses was not a factor of

first importance in establishing their sites. The majority of

the privies are so placed that wastes can be sluiced through

straight channels, and the water-driven mills and mortars

are located at the monastery's edge, where water of an

adjacent stream was apt to be within easy reach. All other

shops and houses are placed in such a manner as to tie them

without difficulty into a logical and simple water system.

Figure 53 shows how easily a well-planned system of

waterways could be superimposed upon the Plan of St.

Gall.

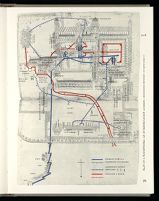

52.A PLAN OF A WATERWORKS:

CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity Library, Cambridge]

This plan of Christchurch waterworks, together with a supplementary and unfinished

plan of the extra-mural parts of the same waterworks, is inserted as a foreign leaf in

the famous Canterbury Psalter (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, ms. 110, fols. 284b

and 285). The plan dates around 1165 and was probably drawn by Wibert (d. 1167).

It is reproduced here slightly reduced from its original size of 11⅝″ × 16⅝.

For a detailed description and a brilliant analysis of the principles of delineation used in

making this extraordinary drawing, see Willis, 1868, 158ff and 176ff. Additional

literature is cited in James, 1935, 53.

52.B PLAN OF A WATERWORKS: AN INTERPRETATION

CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY

[analysis by Willis, 1868, modified by Wysuph, Horn, Born, 1975]

52.C DESCENT BY GRAVITY FROM SUPPLY SOURCE

AT A HIGHER LEVEL TO TERMINAL

DEBOUCHEMENT

The delineation of Christchurch Monastery tells more as pictorial representation, and

of architectural appearance, than it reveals of functional building planning: waterways

shown are schematic. The document shows a water source on high ground, east of the

Monastery, flowing through five (settling?) tanks in cornfields, vineyards, and orchards,

through the monastery wall to Laver I (east cloister), thence to Laver II (Great

Cloister), thence returning on the east to Laver III. This waterway, with Lavers I,

II, III, may be taken as the primary supply system (solid blue line in Plan and

Diagram). Three secondary branches (segmented blue line) are designated on Plan

and Diagram as 1, 2, 3.

Branch 1 leaves the main line between Lavers I and II, flows southward to a

cemetery fountain, then on to debouche in the Piscina. Branch 2 flows northward

from Laver II to a point south of the Brewery where it turns abruptly eastward to

serve the monk's bathhouse, then flows southward to a tank or catchbasin (M) on the

drainage line (solid red line). Branch 3, departing where Branch 2 flows eastward,

serves the Brewery. A short eastward leg serves the Bakery, a short westward leg, the

Abbot's House. From Laver III, at the end of a short extension eastward, the

primary line terminates, draining into the Piscina (blue dotted line).

In addition to the potable supply system a scheme of drainage (red), more or less

polluted, is discernible. Originating in the Great Cloister, it descends southward and

terminates beyond the walls on the north.

The interpretation (figs. 52.B, 52.C) assumes that the drainage line (red), descending in

a short arc from Vestiarium to abut the roof line on the infirmary complex, continues

directly northward through or under the structure to join the drainage system (from

Piscina and tank M) at or near the Infirmary toilets; thus, non-potable water never

comes in contact with the Piscina.

Benedicti regula, chap. 66; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 140-41; ed. McCann,

1952, 152-53; ed. Steidle, 1952, 320-21.

Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones, I, ch. xxix, ed. Mynors, 1937,

73-75, and translation by Leslie Webber Jones, 1946, 131.

Vitae Galli auctore Walahfrido, Book I, ch. 11 and Book II, ch. 10;

see Vita Galli confessoris triplex, ed. Krusch, 1902, 292 and 319; and

Sankt Otmar, ed. Duft, 1959, 24-25.

Catalogus abb. Fuldensium, see Schlosser, 1896, 121, No. 386. For

more information on monastic water power see the chapter on "Facilities

for Milling, Crushing and Drying of Grain," II, 225ff.

Around 835 Abbot Habertus of Lobbes tried to cut an aqueduct

through steep mountain slopes to put it into the service of his mills but

failed and was forced to abandon his project. Folcuini gesta abbatis, chap.

12; see Schlosser, 1896, 67, No. 237.

The Canterbury Psalter, Trinity College Library, Ms. 110, fols. 284b

and 285; see M. R. James, 1935, last two plates.

The Vita prima sancti Bernardi is in Migne, Patr. Lat. CLXXXV:1,

1879, cols. 225-380 (excerpts in Mortet-Deschamps, II, 1929, 23-27).

It consists of five books of composite authorship, written between ca.

1145 and 1155, by men who all had been friends of St. Bernard and

were eyewitnesses to the events described in their accounts. For further

details, see Williams, 1927, 7ff.

I.13.6

PERIPHERAL ENCLOSURE WALL

Whether built of wood or stone, or simply in the form of a

hedge, the outer monastery wall is an intrinsic expression of

the concept of monastic seclusion. In 320, when St.

Pachomius founded the earliest Christian coenobium in

Tabennessi near Dendera in the Upper Nile Valley, he

surrounded it with a wall,[280]

perhaps not so much for

defensive purposes as for insulating the monastic enclosure

from the noise and impurities of the secular world. The

wall became the symbol of monkish self-determination and

collective integrity.[281]

Medieval texts distinguish time and

again between that which is "within" (infra, intrinsecus) or

"without" (extra, extrinsecus, foris, subtus, juxta), which

presupposes a separating enclosure.[282]

In Irish and Anglo-Saxon

monasteries this enclosure often consisted of earthen

ramparts with a moat or ditch in front and a wooden

palisade above,[283]

or even more simply, just a hedge of thorn

(sepes magna spinea, quae totum monasterium circumcingebat),

as at the monastery of Oundle, a foundation of Wilfrid.[284]

A

wooden palisade enclosure existed at the monastery of

Lobbes as late as the twelfth century,[285]

but from the end of

the eighth century, monastery walls were with increasing

frequency built of stone;[286]

and from the end of the ninth

century, many of these walls assume a distinctly defensive

function (murus in modum castri).[287]

In view of these facts, the absence of a peripheral wall

enclosure on the Plan of St. Gall presents a puzzle. Was it a

feature so self-evident to the inventor of the scheme that he

did not bother to include it? Ot should we presume that it

existed on the original, but was omitted in the copy?

There are two reasons why I believe that it existed on the

original. First, the fences that separate the grounds of the

houses to the north and the south of the Church were useless

unless they connected with a peripheral wall enclosure.[288]

Second, our analysis of the scale and construction

methods used in the Plan will show that the location of the

axis of the Church as well as the major site divisions of the

monastery are related to a system of framing lines (fig. 62),

which on the original would only have meaning if they

defined an outer wall enclosure.[289]

The copyist might have dropped this feature for various

reasons: for one, simply because his sheet of parchment

was not large enough to include it; for another, because a

rectangular wall perimeter may have been meaningless on

the reconstruction of the monastery of St. Gall for which

the copy was to be used. The monastery of St. Gall was

wedged into an irregular area shaped by the capricious

course of the Steinach, whose steep embankments may

have served as an acceptable substitute for masonry walls

for a considerable stretch along the southern and eastern

boundaries of the monastery site. No such natural defenses

existed to the west and to the north, where the terrain is

flat. Yet even here there must have been a clear demarkation,

either architectural or topographical, between the

grounds of the monastery and the grounds of the secular

settlement that had begun to rise around it. There is

documentary evidence for the existence, in Carolingian

times, of a protective perimeter of masonry walls. When the

monastery was attacked by the Magyars in 926 the monks

found themselves compelled to throw up a temporary system

of heavy defense (castellum fortissimum) on the spur of a

nearby mountain.[290]

This has been interpreted to mean that

the monastery was not sufficiently fortified to block their

advance.[291]

It was doubtlessly in response to this alarming

event that Abbot Arno, in 953-954, decided to construct a

masonry wall with thirteen towers (muros . . . cum turris

tredecim) that encompassed not only the monastery, but

with it the entire city (urbs) of St. Gall.[292]

This can be inferred from the Rules of St. Pachomius, the earliest

version a translation from Greek into Latin by St. Jerome in 404; see

Boon, 1932. The monastery wall is mentioned in chap. 84 (ibid., 38),

the gate in chaps. 1, 49, 51, and 53 (ibid., 13, 25, 26, 28).

Cf. Lesne, VI, 1943, 48. I cite as a typical example Bishop Haito's

interesting comment on a directive issued during the first synod of

Aachen: "Instruendi sunt fullones, sartores, sutores non forinsecus sicut

actenus, sed intrinsecus, qui ista fratribus necessitatem habentibus faciant.

Statuta Murbacensia" (chap. 5; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963,

444. Cf. Horn in Studien, 1962, 120-21).

A "fosse with palisade" is mentioned in the Rule of St. Columba

(aut extra vallum, id est extra septum monasterii); see Migne, Patr. Lat.,

LXXX, col. 219. The term "septum" also appears in the Life of St.

Columba; see Adamnan's Life of Columba, ed. Anderson, 1961, 218; see

Sowers, 1951, 196.

Gesta abbatum Lobbensium, chap. 23; ed. Arndt, Mon. Germ. Hist.,

Script., XXI, 1869, 326: "Ambitum quoque monasterii idem abbas ad id

tempus sepe lignea ex parte clausum cinxit." That other parts were masonry

can be inferred from a later passage: "Domum etiam hospitum . . . infra

muri ambitum a parte australi aedificiare quidem cepit" (ibid., 327). A

wall entirely of wood was built at St.-Denis by Fulradus, contemporary

of Charlemagne; see Schlosser, 1896, 213, No. 662.

A typical example is the masonry wall Angilbert built around St.Riquier;

see Hariulf, Chronique de l'abbaye de Saint-Riquier, II, chap. 8;

ed. Lot, 1894, 61: "Deo delectentur deservire, ipso adjuvante, muro

curavimus firmiter undique ambire." (Cf. n.9, p. 347 below.)

Lesne (VI, 1943, 49) notes that when Jean de Gorze rebuilt the wall

in the tenth century, he made it like that of a fortress, able to withstand

seige: "Primum claustram muro in modum castri undique circum sepsit quod

hodieque non modum munitiones, set et se opus sit oppugnationi adesse

perspicitur" (see Vita Johannis Gorziensis, chap. 90; ed. Pertz, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Script., IV, 1841, 362).

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 51; ed. Meyer von Knonau,

1877, 193-98; ed. Helbling, 1958, 104-5. See Duft, 1957, 43-47.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chaps. 71 and 136; ed. Meyer

von Knonau, 1877, 250-54 and 431-34; ed. Helbling, 1958, 131-32 and

226-27. See Duft, 1952, 24-34; Duft, 1957, 48-52.

I.13.7

PRIVIES

With regard to privies either the designer of the original

scheme or the copyist was guilty of an oversight. The

apartment of the master of the Infirmary and the adjacent

room for those who are critically ill (fig. 236) lack this

facility. It is obvious that privies of the same design as

those provided for the master of the novices and for the

sick room of the novices were needed in the Monks'

Infirmary in the portion that corresponds exactly to the

Novitiate.

In all other cases where privies are missing, I believe

they are left out intentionally.[293]

More will be said about this

in the chapter on monastic sanitation.[294]

Privies are absent from houses of the gardener, fowlkeeper, workmen,

Hospice of Pilgrims and Paupers, and all houses for animals and keepers

in the service yard west of the Church, as well as in the house for the

emperor's entourage, also located in that tract.

I.13.8

KITCHEN FOR SERFS AND WORKMEN

The ensemble of buildings shown on the Plan of St. Gall

includes no fewer than six kitchens: the Monks' Kitchen[295]

(drawn with all of its furnishings), the Abbot's Kitchen,[296]

the Kitchen for the Novices,[297]

the Kitchen for the Sick,[298]

the Kitchen for the Distinguished Guests,[299]

and the

Kitchen for the Pilgrims and Paupers.[300]

In view of the

meticulous attention given to the need for all of these

installations, we are surprised to note the absence of a

kitchen and dining hall for laymen. The aggregate number

of serfs, workmen, and servants living within the monastic

enclosure, as a rule, exceeded that of the monks.[301]

Where

did they eat? Clearly, not in the Refectory. This would be

impossible not only because there is no entrance into the

Refectory for the serfs and servants; but also because a

regulation of the Second Synod of Aachen (817) prescribes

"that laymen should not be conducted into the refectory

for the sake of eating and drinking" (Ut laici causa manducandi

uel bibendi in refectorium non ducantur).[302]

Emil Lesne's contention[303]

that the meals of the servants

were not prepared in the Monks' Kitchen is right, in my

opinion, if for no other reason than because of the differences

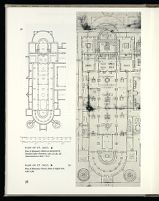

PLAN OF ST. GALL

WHAT SCHEME OF WATERWAYS?

The Plan invites speculation concerning the water supply for the needs of the monastic

population and the removal, beyond the confines of the site, of wastes and waters polluted

by man and beast. The Plan does illustrate, as a paradigmatic concept, the composition

of structures. But what conditions, topographic, hydrographic, climatic (winds, snow,

rain) governed considerations for site selection?

Essential to the operation and good health of the monastery were good drainage, an

adequate supply of potable water, and a well-functioning scheme of sanitation, all

conditions related to the type of terrain. The site illustrated in figure 53 is entirely

assumptive. Contours provide downslope to the south: a downslope to the west of

about 15 feet in the length of the Plan is shown, (roughly 0.25 inch per foot, or 25

inches per 100 feet). That of 83 privies shown on the Plan, 74 are on or near the

north and east boundaries, may or may not allude to planning for odors as related

to prevailing winds, or to a system by which, for most of the privies, excreta could

be removed by water-carriage for building sites on terrains where generous slope and

abundant water supply existed.

Besides solid wastes, sewage comprises water fouled from baths, kitchen use, lavatories,

and also surface drainage from rain or snow. These fluid wastes may have been

removed by surface channels, or by subsurface conduits, probably of terra cotta made

with nesting joints (such as present day "bell and spigot" clay pipe). Drinking

water is best distributed by conduit with tight or sealed joints to prevent leakage and

contamination from without. These two waterways, supply and waste, must be

distinct and separate at all points through their full length.

Bronze and lead, and sometimes wood, were used for piping by the Romans. Delivery

of drinking water by horse drawn tank or barrel was possible. Probably all of these

materials and modes of water supply and disposal of sewage were in use for a

monastery of the period and, no doubt, varied according to the availability of materials,

the skill of local craftsmen and the level of technology of the region.

On sites where no water was available for sluicing of sewage, surface or underground,

excreta was probably disposed in pits or middens, and treated with ashes or floor dust

and sweepings, then removed at intervals and applied as manure on neighboring

ground. From the agricultural view this was sound practice; from the view of hygiene,

not to be tolerated. Nevertheless, such practice existed and exists today in some

communities.

While the 50 privies along the north boundary suggest planning for a system of

sewage removal, the mills and mortars on the south boundary imply the presence of

a running stream as a power source for their operation.

It is notable that only those buildings of the Plan designated for occupancy by clerics

or by men of noble status are provided with privies. The various buildings for essential

services to the monastery, including services requiring high expertise (cooking, beer

and wine making, goldsmithing, etc) have no privies. These men, about 70 percent

of the monastery population, made shift for themselves according to the customs of

the time and the regulations of the establishment.

The nine privies in Building 4, the Monks' Toilets (adjacent to Building 3, the

Monks' Dormitory) attached to the core of the Plan, pose a problem for sewage

removal. A surface sewage ditch does not seem likely here in the midst of clean

water lines; removal from this central location in underground conduit by water

would be no small feat even if feasible. The proximity of these privies to the Monks'

Vegetable Garden X and the Monks' Orchard Y may indicate that an agricultural

destination for human wastes produced in Building 4 was intended.

Figure 53 suggests how, within the scheme of topography shown, supply lines could

penetrate the east boundary of the site. Interior branches we do not show.

The Plan of St. Gall, by the careful ordering of its structures, could adapt well

to an engineered system of water supply and waste drainage consonant with the state

of the art of the plumber and the sanitary knowledge of the time.

E. B.

SCALE: ⅛ ORIGINAL SIZE (1:1536)

to eat meat; the servants were not.[304] To provide two

completely different menus in a kitchen not more than 30

feet square for about 300 people[305] would not have been

feasible.

The 370 pigs that the monastery of Corbie hung in its

larder annually were for the serfs, the guests, and the sick.[306]

Abbot Wala of Corbie (826-833), in his list of monastic

officials, mentions a cellerarius familiae, i.e., a cellarer for

the laymen, who is subordinate to the prior, and provides

the monastery's servants with their drink.[307]

Hildemar (845850)

in his commentary to the Rule of St. Benedict refers

to a monk whose special task was to take care of the serfs'

needs for food and drink.[308]

Yet nowhere in the vast body

of Carolingian consuetudinaries, or for that matter in any

other contemporaneous sources as far as I know,[309]

is there

any evidence for the existence of a kitchen for laymen.

The Plan of St. Gall, I believe, enables us to solve this

puzzle. It suggests that the meals of the serfs and the

servants were cooked in their own houses, which differ

from those of the monks in that they were furnished with

hearths and in this way equipped for the cooking of meals.[310]

The serfs apparently continued within the monastic enclosure

to eat as they had before they entered the monastery's

service and to live in the same kind of houses.

Had the serfs and workmen eaten at a common table,

their considerable number would have required the monastery

to have been provided with a dining hall and kitchen

even larger than that provided for the monks. The absence

of such structures on the Plan cannot be interpreted as an

oversight or omission, because presumably the dining

arrangements were handled in quite a different way.

It would nevertheless be unreasonable to assume that

every layman cooked his own meals. In fact, this was probably

not even done by every group of servants living

together in a given house. It is more logical to assume that

the meals for the lay servants were prepared and eaten in

two or three of the larger service structures strategically

located so as to accommodate people living in different

parts of the enclosure. I feel this view is supported by an

unusual arrangement in the House for Horses and Oxen

and Their Keepers.[311]

This house is provided with a large

central hall with benches all around its walls, offering sitting

space for forty-three people (fig. 54). The hearth is three

times as large as the hearths in the other houses and

has inscribed into it an

might well stand for the kind of boom or rigging that in the

Middle Ages was used to hang pots over open fires. It is

here, in my opinion, that the meals were cooked and eaten

by all the serfs and herdsmen who lived west of the Great

Collective Workshop.[312]

The latter house, too, may have

served a similar purpose. It is occupied by men of higher

skills and its yard is separated from that of the herdsmen

by a conspicuous fence. A third center of this kind may

have existed in the area of the gardeners and the fowl-keepers.[313]

54. PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN (BUILDING 33, SEE PLAN PAGE XXIV)

The hall of this building (DOMUS BUBULCORUM ET EQUOS SERUANTIUM) may have served as kitchen and dining space for herdsmen of this

and other houses. Its unusually large hearth, and benches ranging around the walls, offering seating for over forty people, appear to attest

communal use of this space.

56. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Plan of Monastery Church as interpreted by

Ostendorf [after Ostendorf, 1922, 42, fig. 53]

(Illustrated above at about 1:600)

55. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Plan of Monastery Church, shown ½ original size,

scale 1:384

Dr. Joseph Semmler, too, with whom I have had the pleasure of

corresponding about this matter, is not aware of the existence of any

other documentary sources that would throw further light on this

question. Chapter 26 of the first synod of Aachen (816) prescribes: "Ut

seruitores non ad unam mensam sed in propriis locis post refectionum fratrum

reficiant quibus eadem lectio quae fratribus recitata est recitatur" (Synodi

primae decr. auth., chap. 26; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 465).

One might feel tempted to interpret this directive as referring to the

serfs and workmen, as Emile Lesne has done (op. cit., 194), but the

servitores mentioned in this resolution are not the monastery's lay

servants, but the "servers" (servitores or hebdomadarii) who are chosen

from among the monks for a weekly term of kitchen duty (see below, p.

279f.). A proper translation of this chapter would read: "That the

servers take their meal, not at one table, but each at his proper place [i.e.,

the place in the Refectory assigned to him according to the date of his

entry into monastic life] after the brothers have eaten, and that they be

given the same reading as was given to them." It is in this sense that the

passage was interpreted by Semmler, 1963, 44.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||