The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. | I |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

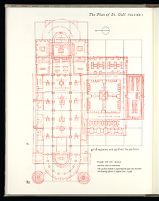

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I

PREVIOUS LITERATURE,

ORIGIN, PURPOSE,

AND SPECIAL PROBLEMS

I. 1

PREVIOUS LITERATURE

INTRODUCTION

ONE of the most remarkable facts about the Plan of St. Gall is that it still exists and that it is still at St. Gall. Aside

from the length of time that has elapsed since the days it was first made, there were several specific dangers that

threatened its existence even after it was incorporated into the Library of St. Gall, such as the sack of the Magyars in

926, in expectation of which all the books were evacuated to the monastery of Reichenau,[1]

and the stormy days of

secularization at the close of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth which spelled disaster to so

many other monastic libraries.

In addition to these external dangers there were those created by the Plan's unusual shape. Being a sheet of

parchment of unwieldy proportions it was subject to the same hazards of housekeeping that tend to beset all holdings

that do not fit neatly into a normal shelving system. That the Plan survived at all under these circumstances must be

credited—as Johannes Duft has correctly pointed out[2]

—to an unknown monk of St. Gall who, at the close of the

twelfth century, availed himself of the unused back portions of the skin to inscribe upon it the text of a Life of

St. Martin. Conscious perhaps of the important role this document had played in the renovation of his monastery

and crosswise into a sequence that furnished him with fourteen pages for his text, plus two empty pages that

served as covers (fig. 1).[3] Thus the physically unmanageable Plan was transferred into a book-sized volume that

could easily be incorporated into a conventional shelving system.

The author of the Life of St. Martin did not proceed with equal wisdom when he discovered toward the end of

his task that the back of the Plan was not large enough to accommodate all of his text. With his mind set on finishing

his work, he turned the Plan over and entered the last twenty-two lines of his text on the lower left corner of the

front side of the Plan. In order to use this portion of the parchment for his text, he erased the lines and explanatory

legends of a large building that occupied the northwest corner of the monastery site (fig. 1.X).

When the books were brought back from Reichenau, according to

Ekkehart "the number was the same, but not the books" (nam cum

reportarentur, ut ajunt, numerus conveniebat, non ipsi). Ekkeharti (IV.)

Casus sancti Galli, chap. 51; ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 193-98;

ed. Helbling, 1958, 104-5. For further accounts of events that might

have threatened the survival of the Plan, see Duft, 1952, 36-38; and

Duft, in Studien, 1962, 33-36, as well as the literature quoted there.

This Vita sancti Martini (not known to the editors of the Bibliotheca

Hagiographica Latina) was first examined by P. Lehmann, in 1947,

after the Plan had been freed from its seventeenth or eighteenth century

backing of linen. Lehmann found it to be not without hagiographical

merit. He describes it as a judicious compilation and alignment of a

number of widely distributed narratives of the life and miracles of St.

Martin, written in St. Gall, in a careful gothic minuscule used toward

the close of the twelfth century in southwest Germany and northeast

Switzerland.

For details see Lehmann, 1951, 745-51; with regard to the chapter

sequence and its relation to the folding system of the Plan, see Schwarz,

1952, 35.

I.1.1

FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE

MIDDLE OF THE 19th CENTURY

The Plan was thus made subservient to a hagiographical

text of lesser importance, and in this new association—

as the subsequent history shows—its original meaning fell

into oblivion. In a fragmentary catalogue of the holdings

of the Library of St. Gall, which was written in 1461 under

Abbot Kaspar of Breitenlandenberg, the document is

listed as a "large animal skin with the life of St. Martin

written upon it and a delineation of the houses of his

monastery" (pellis magna continens vitam S. Martini

scriptam structuramque domorum eius depictam). The author

of this catalogue, as is obvious from this entry, considered

the text on the back of the skin to be the principal part of

this document and interpreted the drawings on the front

of the skin as an outline of the monastery of St. Martin at

Tours.[4]

The true character of the Plan was rediscovered by

Henricus Canisius who in 1604 published the verses of the

Plan,[5]

primarily for their literary interest. Canisius (d.1610)

was unaware of the paradigmatic character of the Plan but

thought it was a site plan of the monastery of St. Gall

"as it looked at the time of Abbot Gozbert." He was the

first to identify the "Cozb[er]tus" of the dedicatory legend

with Abbot Gozbert, who presided over the monastery of

St. Gall from 816-836, and inferred correctly from the fact

that the abbot was addressed as "my sweetest son"

(dulcissime filie) that the author of the Plan was a man of

higher rank and must have been a bishop.[6]

One of the

consequences of the rediscovery of the Plan by Canisius

was that some time in the seventeenth or eighteenth century

(the date can no longer be established) the Plan was

strengthened with a backing of linen, which concealed the

Life of St. Martin.

On the basis of the interest awakened by Canisius, the

great Benedictine scholar Jean Mabillon (1632-1707)

featured in the second volume of his Annales ordinis

sancti Benedicti[7]

the first graphical reproduction of its

explanatory titles. This engraving was neither complete nor

free of errors, but being published in a widely distributed

historiographical work, made the contents of the Plan

accessible to the learned world.

"Extat in bibliotheca S. Galli Tabula quaedam seu (ut vocant) mappa

sane per quam vetusta et ampla ex pergameno ad Gozpertum Abbatem, in

qua etiam totum monasterium secundum omnes etiam abiectissimas officinas

descriptum est (ut quidem ego colligo ex eo, quod ibi appellat author Gozpertum

filium) ab Episcopo aliquo, qui fuerit vel Monachus, vel studiosus,

vel certe alias demum Monachis et Monasterio familiaris. Eam tabulam

index quidem centenarius nominat S. Martini Monasterii, ex eo, ut arbitror

quod aliquid in tergo ipsius est vita S. Martini, sed ut ex titulis et situ

manifestum est, non est, nisi S. Galli Monasterii, prout fuit Gozberti

temporibus Monasterium" (ibid.).

I.1.2

THE FIRST MONOGRAPHIC STUDIES

It took another 140 years for the Plan to become the

subject of a separate study. The first monographic treatment

of the Plan was published in 1844 by Ferdinand

Keller, the founder of the Antiquarische Gesellschaft of

Zurich.[8]

It included as a novelty an attempt to interpret

the construction of the buildings shown on the Plan. Keller

intended to publish a full scale lithographic facsimile edition

of the Plan, but the stone on which the design was drawn

broke apart during the first printing and was subsequently

replaced by a smaller stone on which the outlines of the

Plan were reduced to four-fifths the original size. The

explanatory legends were superimposed in their original

dimensions upon this reduced image, and in this discordant

description of its drawings and legends.

Although by no means free of errors and omissions—

the most serious of which is the omission of the dedicatory

letter—Keller's "facsimile" nevertheless was an excellent

specimen of lithographic reproduction and formed the

basis for all future research. In the English-speaking world

the Plan became known through an enlarged and annotated

translation of Keller's text by Robert Willis, published in

the 1848 volume of the Archaeological Journal;[9]

in France,

through Albert Lenoir's treatment of the subject in his

Architecture monastique of 1852,[10]

and through a translation

of Willis into French by M. A. Campion,[11]

which appeared

in the Bulletin monumental of 1868. The latter formed the

basis of Leclercq's widely read description of the Plan of

St. Gall in Cabrol-Leclercq's Dictionnaire d'archéologie

chrétienne et de liturgie[12]

which added nothing original to

the study of the Plan.

I.1.3

ENTRY OF THE SPECIALISTS

It was only natural that the Plan of St. Gall, once

published, should become an object of primary attraction

to the students of vernacular architecture who were not

slow in recognizing its signal importance for the history of

medieval house construction. This aspect of the Plan was

the concern of such men as J. R. Rahn (1876), Rudolf

Henning (1882), Julius von Schlosser (1889), Moriz Heyne

(1899-1903), Karl Gustav Stephani (1902-3), Christian

Rank (1907), Franz Oelmann (1923-24), H. Fiechter-Zollikofer

(1936), Otto Völkers (1937), and Karl Gruber

(1937 and 1952).[13]

Of deeper and even wider impact were the discussions

raised by the design of the Church and the claustral

structures of the Plan, as well as by certain discrepancies

between the drawing of the Church and the measurements

given in its explanatory titles. The literature of these

subjects has swollen into discouraging proportions. It

includes the writings of such men as: Hugo Graf (1892),

Georg Dehio (1892 and 1930), Wilhelm Effman (1899 and

1912), August Hardegger (1917 and 1922), Friedrich

Ostendorf (1922), Joseph Hecht (1928), Ernst Gall (1930),

Joseph Gantner (1936), Hans Reinhardt (1937, 1952, and

1962), Edgar Lehman (1938), Fritz Victor Arens (1938),

Otto Doppelfeld (1948 and 1957), Walter Boeckelmann

(1956), Wilhelm Rave (1956), Karl Gruber (1960), and

Wolfgang Schöne (1960). Landmarks in this sequence of

studies were the articles of Otto Doppelfeld (1948) and

Walter Boeckelmann (1956), each of which offered a new

solution to the difficult problem of the "dimensional

inconsistencies" of the Plan. Less successful were Wolfgang

Schöne's (1960) and Adolf Reinle's (1963-64) attempts

to settle this question.

The thorny problem of the origin of the cloister was

studied by Julius von Schlosser (1889), Joseph Fendel

(1927), and Ossa Raymond Sowers (1952). To add to these

names the countless references made by other authors who

addressed themselves to various aspects of the Plan in studies

not specifically devoted to this subject would be a

hopeless and unrewarding task.

An indispensable reference work that no student of the

Plan can by-pass is Hermann Wartmann's exhaustive

publication of the documentary sources of St. Gall (186392).[14]

An informative review of the economic history of St.

Gall, based on this material, is Hermann Bikel's Wirtschaftsverhältnisse

des Klosters St. Gallen;[15]

a valuable

study of the monastery's literary and scriptorial activities is

J. M. Clark's The Abbey of St. Gall, as a Centre of Literature

and Art.[16]

For the titles of the works cited here and in the subsequent paragraph,

see Bibliography, Vol. III.

I.1.4

A NEW ERA: THE FACSIMILE

EDITION OF 1952

A new era in the history of the investigation of the Plan

was initiated in 1952 with the publication, under the

auspices of the Historische Verein des Kantons St. Gallen,

of a facsimile reproduction of the Plan.[17]

This praiseworthy

undertaking was initiated and carried out by the

late Hans Bessler of St. Gall and his lifelong friend Dr.

Johannes Duft, the distinguished director of the Stiftsbibliothek,

who together nursed this project through all its

critical stages.[18]

Printed by the most advanced methods of

color reproduction, this facsimile has not only secured the

survival of the Plan in hundreds of widely distributed

copies, but has also opened the field for new studies on the

scale and construction methods used in the laying out of

the buildings shown on the Plan.[19]

The 1952 facsimile was accompanied by a descriptive

text by Hans Reinhardt,[20]

which appeared as the 92.

Neujahrsblatt of the Historische Verein des Kantons St.

Gallen, together with an article by Johannes Duft on the

previous history of the Plan,[21]

an analysis by Dietrich

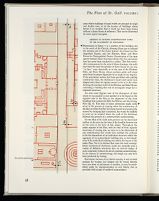

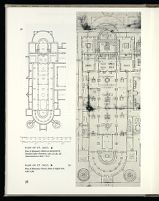

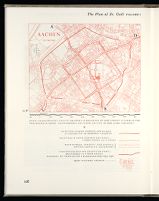

1.A PLAN OF ST. GALL

VERSO OF THE PLAN WITH THE LIFE OF ST. MARTIN INSCRIBED MORE THAN THREE

CENTURIES AFTER THE PLAN WAS DRAWN ON THE RECTO.

THE PLAN OF ST. GALL

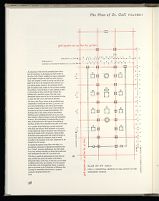

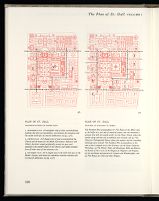

The first fold divided the parchment into

two equal areas. The and & 3rd foldings

were then made to the first

fold.

For ease in folding the outer rows X and Y

were made slightly shorter than the two center

rows.

1.B

Compactly folded the manuscript can

now be returned to the library shelf.

The blank space (space with no

writing) functions as front and back

cover.

THE LIFE OF ST. MARTIN AND THE FOLDING OF THE

PARCHMENT IN RELATION TO THE READING SEQUENCE

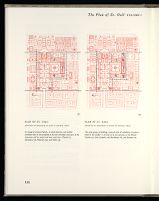

1.C

THE UNFOLDING PROCEDURE AND READING SEQUENCE

The scribe planned the LIFE OF ST. MARTIN to be easily read with the pages

following each other in numerical order from left to right. The reader, on taking the

manuscript from the shelf, had in hand a "package" as shown in fig. 1, diagram 8.

Laying the LIFE on the table, the reader opened the package. Before him, in

normal reading position, he saw page 1 on the left and page 2 on the right:

After reading pages 1 and 2, page 1 was turned backwards (on fold line 4) to the

left, and page 2 was turned to the right (on fold line 5). The reader then saw a

rectangle like this:

The row of pages 3, 4, 5, 6, was brought toward the reader and laid flat on the

table. This is what he saw—pages 7, 8, 9, 10, in reading sequence left to right:

So far the page numbers flowed in normal sequence, left to right. Page 11, however,

was clearly in view but upside down. The parchment was rotated 180 degrees to

permit the upside-down pages to be read.

After reading the sequence of pages 11, 12, 13, 14, left to right, in fig. 5, the

parchment was rotated back to the position shown in fig. 4. There was more to be

read; 14 was not the last page of the LIFE OF ST. MARTIN.

At this stage, the reader lifted the lower row of pages, 7, 8, 9, 10 (on fold line 3),

toward him and placed the parchment face down on the table. This is what he saw:

In the lower left corner, on the back of page 7, in reading position and clearly in

view, was the last page of the LIFE OF ST. MARTIN, page 15.

On the remainder of the parchment, intact and without erasure, was displayed

Haito's Plan of St. Gall: a graphic configuration, a senseless geometric abstraction.

Three centuries after its conception and delineation, it was neither with meaning

nor historical significance to a reader of the LIFE OF ST. MARTIN, until its

discovery or rediscovery in 1604 by Henricus Canisius (See p. 2, above).

We can be grateful that the LIFE OF ST. MARTIN was not treated to conventional

bookbinding techniques composed of cut leaves, folded and sewn into signatures.

The marvel of the survival of the parchment has been treated by Dr. Johannes

Duft (see above, p. 1, note 1).

the twelfth-century monk,[22] and a report by Hans Bessler,

on the technical measures taken for the preservation of the

Plan.[23]

Reinhardt did not propose to undertake a comprehensive

treatment of the subject and did not claim to deal with it in

an exhaustive manner. He offered a new solution to the

controversial issue of the inconsistent measurements of the

Church, and advanced some new thoughts about the origin

of the two circular towers, but touched only briefly on the

difficult problem of the reconstruction of the guest and

service structures of the Plan.

In 1949, during the preparatory stages of this great

facsimile edition, while the Plan was under photographic

examination in the Landesmuseum of Zurich, it was

freed from the linen backing with which it had been reinforced

during the seventeenth or eighteenth century.[24]

This brought to light the text of the Life of St. Martin

which covered the verso of the Plan. X-rays and other

penetrating photographic methods brought back the

outlines of the erased large service structure in the northwest

corner of the monastery (fig. 405), but failed to revive

its explanatory titles.[25]

The last hope that these legends

could ever be recovered vanished when Dr. Duft discovered

that they belonged to a group of obliterated texts

that had fallen victim to the chemical experiments undertaken

either by the distinguished historian Ildefons von

Arx (1755-1833), or perhaps by Anton Henne, who served

as provisional librarian between 1855 and 1861.[26]

Der Karolingische Klosterplan von St. Gallen, eight-color facsimile

offset print, published by the Historische Verein des Kantons St.

Gallen, the Clichéanstalt Schwitter and Co., Zurich, and E. LoepfeBenz,

Rorschach.

I.1.5

THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM

AT ST. GALL, 1957

It had been one of the wishes of Hans Bessler that the

publication of the facsimile edition of the Plan of St. Gall

should be followed by a symposium of scholars concerned

with the Plan, and that the work that would emerge from

this gathering should subsequently be made available in a

scholarly publication. Hans Bessler did not live to see both

of these dreams fulfilled. A symposium, organized and

conducted by him and Dr. Johannes Duft, was held in

St. Gall from July 12-16, 1957.[27]

The publication of the

studies that emerged from the symposium had to be undertaken

by Dr. Duft alone and appeared as a memorial for

Bessler under the title, Studien zum St. Galler Klosterplan,

in the Mitteilungen zur Vaterländischen Geschichte, published

under the auspices of the Historische Verein des

Kantons St. Gallen.[28]

It contained, apart from a masterful

review of the previous literature on the Plan by Johannes

Duft,[29]

a fundamental analysis of the paleographical

problems of the Plan by Bernhard Bischoff;[30]

two articles

by the writer of the present study, one on the question of

the originality of the Plan,[31]

the other on the relation of the

Plan to the monastic reform movement;[32]

an article on the

altars of the Plan by Iso Müller, OSB;[33]

a study of Hildemar's

commentary on the Rules of St. Benedict and its

implications for the Plan by Wolfgang Hafner;[34]

a study of

the plants and gardens by Wolfgang Sörrensen;[35]

and two

brief essays by Heinrich Edelmann, one dealing with the

relation of the Plan to the actual building site of the

monastery of St. Gall,[36]

the other with the history of the

three-dimensional model of the buildings of the Plan which

was executed in 1877 by the sculptor Jules Leemann of

Geneva for the Historisches Museum of the city of

St. Gall, where it is still on display.[37]

THE CONTROVERSY ABOUT THE

SCALE OF THE PLAN

A new study dealing with the "dimensional inconsistencies"

and the presumptive scale (or "scales") of the

Plan was published in 1963/64 by Adolf Reinle.[38]

It departs

completely from all previous views expressed on this

subject and offers a radically different interpretation of the

large axial title of the Plan that records the length of the

Church as being 200 feet. The merits and demerits of this

thesis, as well as the opinion of others who had been

intrigued by this problem, were discussed in an article of

my own published in the September-December issue of the

Art Bulletin of 1966.[39]

The old, yet still controversial,

problem "Schema oder Bauplan," was briefly and successfully

reviewed by Konrad Hecht,[40]

in an article published

in 1965, which also offered some new and important

observations about the shrinkage of the parchment upon

which the Plan is drawn, and the relevance of this change

to the interpretation of the scale of the Plan.

Made possible by the generous support of the City and the Canton of

St. Gall, as well as a group of private citizens, this symposium brought

together scholars from Switzerland, Germany, France, and the United

States. The lectures and discussions of the meeting were reviewed by

Poeschel, 1957; and idem, in Studien, 1962, 23-32; Bessler, 1958,

229-39; K. Gruber, 1960, 15-19; Duft, in Studien, 1962, 13-15; and

Reinhardt, in Studien, 1962, 57-64.

I.1.6

COUNCIL OF EUROPE EXHIBITION

KARL DER GROSSE at AACHEN, 1965,

AND ITS IMPETUS

Recently a powerful impetus was given to the study of the

Plan of St. Gall by Dr. Wolfgang Braunfels who invited

the authors of the present work to furnish him with the

research and architectural drawings for a three-dimensional

model of the monastery shown on the Plan, to be put on

held in the city of Aachen in the summer of 1965. The birth

of this book, whose beginning reaches many years back, is

intimately connected with this project, and my gratitude

to Dr. Braunfels for motivating this final push has no

limits. There is no more acid trial for any theoretical

assumptions about the three-dimensional appearance of

buildings known only in simple line projection than that of

testing them in the constructional reality of a scale-drawn

model. As in previous studies posing similar problems, I

found myself in the fortunate position of being able to

draw on the professional knowledge, constructional experience,

and superior draftsmanship of Ernest Born and

Carl Bertil Lund, without whose expert and devoted

collaboration that project could never have been carried

out.[41] We are fortunate, in turn, to have found in Siegfried

Karschunke a model-builder of rare resourcefulness and

impeccable skill. It is on the work-drawings made for this

model that most of the reconstruction drawings of this book

are based. The costs of making these drawings were carried

by the University of California; the costs for the construction

of the model itself by the Council of Europe.[42] A

brief description of the model and the criteria used in the

reconstruction of its various installations was published in

the catalogue of the Aachen Exhibition.[43]

OTHER MORE GENERAL WORKS &

NEW CRITICAL EDITIONS

I cannot conclude this review of the historical and

bibliographical vicissitudes of the Plan of St. Gall without

drawing attention to two further events of vital importance

for this study, neither of them directly concerned with the

Plan. The first of these was the publication in 1910-43 of

the six volumes of Emile Lesne's monumental Histoire de

la propriété ecclésiastique,[44]

a veritable storehouse of

knowledge, harboring a wealth of information on the

monastery as a legal, manorial, administrative, and educational

institution. The second was the publication, in

1963, under the general editorship of Kassius Hallinger,

OSB, by the Pontifical Athenaean Institute of St. Anselm,

in Rome, of the first volume of the Corpus consuetudinum

monasticarum,[45]

a new critical edition of the monastic

consuetudinaries of the eighth and ninth centuries, elucidated

by a critical apparatus of incomparable excellence

and including inter alia the new edition of such crucial

contemporary sources as the resolutions, preliminary and

final, drawn up in 816 and 817 in connection with the two

reform synods of Aachen,[46]

as well as that masterpiece of

administrative and manorial logistics, the so-called Statutes

of Adalhard of Corbie (Consuetudines Corbeienses), drawn

up in January 1821/22 by one of the most distinguished

abbots of the Frankish empire.[47]

A complete translation of

this informative source, by my colleague Charles W. Jones,

will be found in Appendix II.[48]

The publication of this vast collection of monastic

consuetudinaries was preceded and accompanied by a

series of penetrating studies on the monastic legislation

enacted during the reign of Louis the Pious, from the pen

of one of its principal editors, Dr. Joseph Semmler,[49]

which opened new avenues for the understanding of the

monastic reform movement that forms the spiritual home

of the Plan of St. Gall. My indebtedness to the Corpus

consuetudinum monasticarum and the distinguished editors

and commentators is visible in countless places throughout

this book.

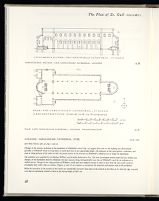

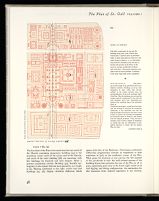

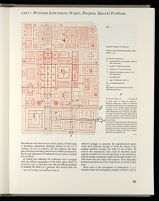

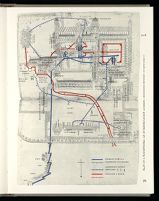

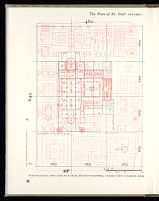

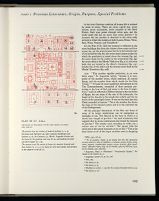

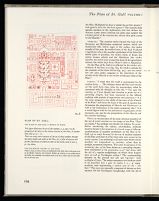

2. PLAN OF ST. GALL: THE DEDICATORY LEGEND

Addressed to Abbot Gozbert of St. Gall (806-836) by a churchman of higher rank who fails to identify himself, this letter of transmission

discloses (in the term EXEMPLATA) that the Plan is not an original but a copy, and therefore presumes the existence of a prototype.

The nature of its scripts reveals that the copy was made in the Abbey of Reichenau, perhaps around 820, but not earlier than 816/817 or later

than 830, the year in which Gozbert began to rebuild his monastery with the aid of the Plan.

The placement of the letter on the Plan's upper margin reveals that this scheme was to be viewed from west to east, not from south to north as

would be the case in similar post-medieval, and modern layouts.

A typographic transliteration of the letter with English translation is shown on the opposite page

Corpus consuetudinum monasticarum, ed. K. Hallinger, I, 1963. Since

these lines were written, this publication was augmented by two further

volumes (II, 1963; III/IV, 1967).

Legislatio Aquisgranensis, ed. Semmler, Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 423-82;

superseding earlier editions of the monastic legislation of 816-817, Bruno

Albers (ed.), Consuetudines monasticae, III, 1907, 79ff. and 115ff.

Semmler, in Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 355-422; superseding an

earlier edition by Leon Levillain, 1900, 338-86.

After the closing of the Karl der Grosse exhibition, the model was

transferred to the Burg Frankenberg Museum, Aachen, and is now under

the guardianship of the Director of the Museen der Stadt Aachen. A

new model, in process of construction, will become the property of the

University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley.

Karl der Grosse, Werk und Wirkung, ed. Wolfgang Braunfels

(Aachen, 1965), 402-10; also published as Charlemagne, Œuvre Rayonnement

et Sarvivances, ed. Wolfgang Braunfels (Aachen, 1965), 391-400.

Also cf. Karl der Grosse, Lebenswerk und Nachleben, for a listing of five

volumes in this definitive series.

I.1.7

THE SCOPE OF THE PRESENT STUDY

The opinions voiced on the various problems raised by

the Plan of St. Gall are numberless and, scattered as they

are in a vast array of books and disparate journals, prove to

be beyond the control of anyone but the most dogged

specialist. The time, therefore, is ripe for a general synthesis

of this scattered knowledge, and for a thorough and

comprehensive review of the issues raised in these

discussions.

Two queries, hitherto unsolved, require special consideration,

and perhaps more space than is desirable in the

context of the summary study that we have proposed. The

first of these is the highly controversial question of the scale

and construction methods followed in the Plan of St. Gall,

its initial mental conception and the actual drawing up of

the original scheme. The second is the question of the

constructional nature of the monastery's guest and service

structures. The former is the most tangled and most

widely debated single issue of the Plan;[50]

the latter, the

most difficult and most complex, but also probably the most

rewarding. To settle it would be a breakthrough, not only

because of the light it would throw on the history of

monastic building, but also because of the contribution it

would make to our knowledge of vernacular architecture

at the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious.[51]

I. 2

THE DEDICATORY LEGEND

I.2.1

WORDING AND IMPLICATIONS

Our primary source of information concerning the circumstances

that led to the making of the Plan is the transmittal

note of seven lines that is written on the upper

margin of the Plan (fig. 2):

Haec tibi dulcissime fili cozƀte de posicione officinarum

paucis exemplata direxi. quibus sollertiam exerceas tuā.

meamq. deuotionē utcumq. cognoscas. qua tuae bonae uolun

tati satisfacere me segnem non inueniri confido. Ne suspiceris

autem me haec ideo elaborasse. quod uos putemus nr̄īs indigere

magisteriis. sed potius ob amorē dei tibi soli pscrutinanda pinxisse

amicabili fr̄n̄itatis intuitu crede. Uale in xp̄ō semp memor nri am̄.

Translated freely into English this text reads:

For thee, my sweetest son Gozbertus, have I drawn this briefly annotated copy

of the layout of the monastic buildings,[52]

with which you may exercise your ingenuity

and recognize my devotion, whereby I trust you do not find me slow

to satisfy your wishes. Do not imagine that I have undertaken this task

supposing you to stand in need of our instruction, but rather believe that

out of love of God and in the friendly zeal of brotherhood I have depicted this

for you alone to scrutinize. Farewell in Christ, always mindful of us, Amen.

This transmittal note provides the following points of

information:

1. In undertaking his task the author of the Plan of

St. Gall had available for his guidance a prototype plan,

since he refers to his own work as exemplata, that is,

"copied."[53]

2. The Plan was to be used for some specific building

program, since it was transmitted to its recipient, Gozbert,

with the remark "with which you may exercise your

ingenuity."

3. The Plan must have been made at Gozbert's request,

since its maker states: "Whereby I trust you do not find

me slow to satisfy your wishes."

4. The writer of the transmittal note was a person of

higher standing in the administrative hierarchy of the

church than its receiver, since otherwise he could not have

addressed him as "my sweetest son."

Like Bernhard Bischoff (in Studien, 1962, 67ff) and Wolfgang Hafner

(ibid., 178ff), I am translating officina in the comprehensive sense of

"monastic buildings" rather than in the limited sense of "workshops"

suggested by Poeschel (1957, and in Studien, 1962, 29ff). Cf. below

pp. 50ff.

Faulty translation of exemplata, past participle of the verb exemplare

—"to copy" or "to transcribe"—has confused the discussion of the

Plan of St. Gall ever since Robert Willis (1848, 87) interpreted exemplare

in the sense of "to make" or "to work out." Keller (1844), Campion

(1868), and Cabrol-Leclercq (VI:1, 1924) by-passed the issue by not

translating the transmittal note. Reinhardt (1937, 277, note 2; and 1952,

16) translated the term exemplare in the sense of "to make by way of

example." The first to suggest that exemplare must be translated in the

sense of "to copy" was Alphons Dopsch (1916, 67). His view was shared

by Konrad Beyerle (I, 1925, 82), and by Hecht (I, 1928, 23). The latter

translated the passage into German: "Mein süsser Sohn Gozbert, ich

habe diese Kopie der Anlage des Klosters an dich gesandt . . ." Bischoff's

convincing arguments (Studien, 1962, 67-68) have settled this problem

once and for all. See also Horn (Studien, 1962, 79-80); and below,

pp. 15ff.

I. 3

ABBOT GOZBERT, ORDERER &

RECEIVER OF THE PLAN

I.3.1

GOZBERT'S IDENTITY

There is general agreement that the "Gozbertus" to whom

the dedicatory legend is addressed is the abbot of this

name who presided over the monastery of St. Gall from

816 to 836, and who around 830 initiated a building program

whose aim was totally to reconstruct this old and

venerable settlement.[54]

That the Plan was made for St. Gall

is suggested not only by the fact that it has been in the

possession of the library of this monastery ever since the

ninth century, but also by the more explicit evidence that

the high altar of the church of the Plan is dedicated jointly

to St. Mary and St. Gall (altare scaē mariae & sc̄ī galli).[55]

An earlier view of Keller's (1844, 11) and Meyer von Knonau's

(1879, 523), according to which the Cozertus named in the transmittal

note was identical with Gozbert the Younger (a nephew of Abbot

Gozbert of St. Gall who is frequently mentioned in documents since 816)

is now generally abandoned; cf. Duft, in Studien, 1962, 42-43.

I.3.2

ST. GALL AT THE TIME OF

GOZBERT'S ACCESSION

In 816, when Gozbert became abbot, the Monastery of

St. Gall must have consisted of an aggregation of unimpressive

and superannuated buildings. The houses of the original

cell, erected in the Irish tradition[56]

had been substantially

remodelled by Abbot Otmar (719-759)[57]

who in

compliance with an order issued in 747 by King Carloman

and his brother Pippin[58]

converted the abbey from the

Irish to the Benedictine rule. This change in custom undoubtedly

necessitated the replacement of the loosely scattered

houses of the original settlement[59]

by a more ordered

claustral complex where the monks slept in a single dormitory

and took their meals in a common eating hall. Just

precisely how this was done, remains obscure. The sources

make it fairly clear, however, that Otmar replaced the

modest timbered oratory of St. Gall with a masonry church,

the nave of which rose to a height of 40 feet.[60]

This building

had beneath its presbytery a crypt sufficiently large to

accommodate not only the sarcophagus of St. Gall, but

also an altar and whatever additional space was needed for

the attendant monks and priests to celebrate religious

services at and around this altar.[61]

As far as the rest of the

monastery is concerned, the sources simply tell us that

Otmar "adapted the layout of the monastery to the diverse

needs by erecting all around dwellings that were suited for

the use by the monks" (undique versum habitacula monachorum

usibus congrua disposite construens eiusdem sancti statum

loci utilitatibus diversis aptavit)[62]

and that this program

included a hospice for pilgrims and paupers as well as a

special infirmary for lepers.[63]

There is no evidence that

Otmar's successors continued this work or improved upon

it. But the history of succeeding decades shows that much

Counts Warin and Ruthard, who imprisoned Otmar and

put him into exile, and that similar infractions were committed

by the Bishop of Constance, in whose diocese the

abbey was located.[64] Economically St. Gall entered into a

period of stagnation, if not actual decline.

The first settlement, built by St. Gall for himself and twelve companions,

consisted of a small wooden oratory, whose entrance was so low

that a thief called Erchuald smashed his head against the door lintel in

making a hasty escape from the sanctuary. The houses of the monks were

likewise built in timber. For a summary on what is known about the

original cell see Poeschel, 1961, 4-6. His sources are chaps. 29 and 30 of

the Vita Galli confessoris triplex, published by Krusch in Mon. Germ.

Hist., Script. rer. Merov., IV, 1902, 229-337.

The most recent discussion of the life and the accomplishments of

Abbot Otmar is to be found in Duft, 1959, where all of the basic sources

are compiled (Latin and German translation).

That it was built in stone can be inferred from the fact that when this

building was demolished in 830 to make room for Gozbert's new church.

its walls were destroyed by a battering ram (muros ecclesiae machinis

aggressi, crebris arietum ictibus ruere compulerunt). Vita sancti Otmari,

chap. 16; ed. von Arx, Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. II, 1829, 46-47. The

height of the church is mentioned in chap. 12 of this Vita where it is said

that a serf fell from the roof of the church with a load of shingles on his

shoulder and, after a fall of "not less than forty feet" landed on the

sarcophagus of the Saint unharmed (cum et altitadine tecti unde supradictus

home cediderat, non minus quadraginta pedum mensura a terra esset

suspensa). Op. cit., 45-60.

The sources are Vita sancti Golli, chaps. 13, 65, and 72. For more

detail see below, pp. 141ff and 169ff.

Liber de miraculis sancti Galli, chap. 10; ed. Duft, 1959, 41-43; and

Vita sancti Otmari abbatis, chap. 1; ibid., 24-25. Poeschel, 1961, 9 seems

to me to strain these sources when he expressed the view that the wording

of these passages suggests that Otmar did not abolish the Irish layout of

the original settlement with its scattered houses, where monks lived in

individual cells.

On the fraudulent alienation of many of the abbey's outlying estates

by the Counts Warin and Ruthard and the infractions committed by

Bishop Sydonius of Constance see Vita sancti Otmari, chaps. 5-7 (ed.

Duft, 1959, 32-35); Liber de miraculis sancti Galli, chaps. 14-17 (ibid.,

44-53); and Ratpert's De casibus sancti Galli, chap. 6 (ibid., 54-57).

I.3.3

ADMINISTRATIVE ACCOMPLISHMENTS,

DECISION to REBUILD THE MONASTERY

Abbot Gozbert not only stopped, but reversed this trend

and thus led the monastery into an age of unprecedented

prosperity. Even in the first year of his abbacy he scored a

brilliant success by obtaining territorial independence from

the see of Constance.[65]

Two years later, in 818, the monastery

was granted the formal immunity of a royal abbey.[66]

In

the years that followed, Gozbert not only retrieved, through

vigorous litigation, the rights and properties that the abbey

had lost through fraud and lawless alienation, but augmented

its wealth beyond all previous standards by his skill

in soliciting additional gifts.[67]

By 830 the monastic economy

had gathered sufficient strength to enable him to launch his

most ambitious project, the monastery's architectural reconstruction.

We are well informed about this project by reliable

contemporary sources that tell us that Gozbert started the

work by destroying the old church, and that he progressed

with the new church so rapidly that it could be dedicated in

837 (one year after his resignation) in the presence of the

bishops of Constance and Basel, and the abbot of the

nearby monastery of Reichenau.[68]

It was Gozbert's need

for proper guidance in the execution of this building project

that had prompted him to request, from a churchman of

higher rank, the copy of a master plan for a monastic

settlement, which we now know as the Plan of St. Gall. To

what extent he used the Plan in pursuing this task will be

discussed in a later chapter.

On the relation of St. Gall to Constance, see Mayer, 1952. For other

literature on Gozbert's achievements, see Duft's "Gozbert," 1964, 692.

The document, which frees the monastery from the control of the

Bishop of Constance and places it under the sole and direct jurisdiction of

Emperor Louis the Pious, is reprinted in Wartmann, I, 1863, 226,

No. 234.

With regard to Gozbert's contributions to the economic growth of St.

Gall, see Bikel, 1914, 10ff; and Hecht, I, 1928, 17.

An excellent summary of Abbot Gozbert's progress in rebuilding the

church will be found in Hecht, ibid., 29ff with ample reference to the

original sources, the most important of which is Ratperti casus sancti

Galli, chap. 16; ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1872, 28ff. Cf. also Poeschel,

1961, 29ff.

I. 4

THE MAKER OF THE PLAN:

BISHOP HAITO OF BASEL?

I.4.1

OTHER CONTENDERS & OTHER VIEWS

Although there is little doubt about the person for whom

the Plan of St. Gall was made, we are not certain about the

identity of the person who made the Plan. In the vast and

steadily increasing body of literature that has been devoted

to this problem ever since the Plan of St. Gall was first

discussed by Henricus Canisius in 1604,[69]

its authorship

has been attributed to such diverse persons as Einhard, the

friend and biographer of Charlemagne;[70]

Gerungus, a

distinguished official at the emperor's court;[71]

Frotharius,

bishop of Toul;[72]

Ansegis, abbot of Fontanella (St.Wandrille);[73]

Hrabanus Maurus, abbot of Fulda;[74]

Reginbertus,

headmaster of the monastic school at Reichenau;[75]

and Haito, bishop of Basel (803-823) and abbot of the

nearby monastery of Reichenau (806-823).[76]

Digot, 1853, 127ff. Digot's attribution of the Plan of St. Gall to

Bishop Frotharius of Toul was based on two arguments: the fact that

Bishop Frotharius was an experienced architect (a capacity in which he

also was employed by the court), and that there was a distinct analogy in

style between the transmittal note of the Plan of St. Gall and the Latinity

of the letters of Bishop Frotharius (the latter have been published by

Dom Martin Bouquet, VI, 1870, 386-98). Both arguments are extremely

tenuous. Digot's views were adopted without modification by Leclercq,

and became widely known through the latter's article, "Saint-Gall,"

in Cabrol-Leclercq, VI:1, 1924, cols. 87-88.

I.4.2

HAITO:

THE MOST REASONABLE CHOICE

Konrad Beyerle, who proposed Bishop Haito as the

author of the Plan, pointed with good reason to the fact

that Haito's dual rank of bishop of Basel and abbot of the

monastery of Reichenau would well account for that peculiar

blend of paternal condescension ("my sweetest son

Gozbertus") and brotherly devotion ("in the friendly zeal

of brotherhood I have depicted this for you") that characterizes

the spirit of the address with which the author of the

Plan transmits the product of his labors to Gozbert.[77]

Reinhardt rejects this line of reasoning with the argument

that, as bishop of Basel, Haito could not have addressed

Abbot Gozbert as "my sweetest son," because the abbey

of St. Gall lay in the diocese of Constance, not Basel, and

therefore Haito was not his direct superior.[78]

It is true that

even after it was granted manorial independence, in 816,

the monastery of St. Gall remained under the ecclesiastical

jurisdiction of the See of Constance, but the contention

that only the direct superior could address an abbot in this

manner is not based on historical evidence. Whatever the

boundaries of his diocese, in the hierarchy of the church,

the bishop held the higher rank.[79]

To be sure, Haito was not the only bishop in the empire

of Louis the Pious to hold an episcopate and an abbacy at

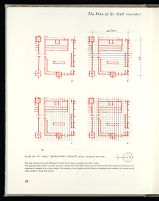

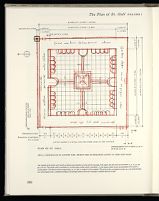

3. PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR HORSES & OXEN & THEIR KEEPERS

Detail showing writing of both scribes

as abbot of Reichenau, Haito was a close neighbor of Abbot

Gozbert of St. Gall and therefore unquestionably well

acquainted with him.

None of the other contenders for authorship of the Plan

of St. Gall have these qualifications. Einhard was trained at

Fulda and in the palace school at Aachen, and while as the

emperor's personal friend and adviser he played a prominent

role at the court, he never rose to a church position

higher than that of abbot.[81]

The name of Gerungus, who

held the rank of an ostiarius at the Palace of Aachen, has

never been taken seriously by any student of the Plan,

apart from its original proponent, and was convincingly

refuted in 1884 by Joseph Neuwirth.[82]

Hrabanus Maurus,

the famed abbot of Fulda, was trained in the schools of

Fulda and Tours, and rose to the rank of bishop only

toward the end of his life, in 847.[83]

Abbot Ansegis of

St.-Wandrille was trained in St.-Wandrille and possibly at

the palace school of Aachen.[84]

Bishop Frotharius of Toul,

the only one besides Bishop Haito of Basel who would have

qualified by virtue of rank, was schooled in the monastery

of Gorze.[85]

Reginbertus, lastly, the headmaster of the

school of Reichenau, who would have qualified by virtue

of his training, stood in no relation to Abbot Gozbert that

would justify the address dulcissime fili.[86]

This leaves

Bishop Haito of Basel as the only reasonable choice among

all the persons proposed as makers of the Plan.

Moreover, new weight was added to this view in 1957 by

Bernhard Bischoff's careful paleographical analysis of the

textual annotations of the Plan, which showed that the

explanatory titles were written in the monastery of

Reichenau.

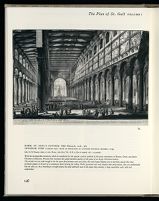

4. PLAN OF ST. GALL

NORTH PORCH OF WESTERN PARADISE

First three lines by second scribe, last three lines by main scribe

The jurisdictional authority of the bishop over the abbot had been

established by St. Benedict of Nursia in chapters 62, 64, and 65 of his

Rule (see Benedicti regula, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 144ff; ed. McCann, 1952,

140ff; ed. Steidle, 1952, 302ff) and was continually reasserted in the

Middle Ages despite unceasing attempts on the part of the abbots to free

themselves from episcopal control. See the pertinent remarks on the

episcopate and monachism in Hauck, II, 1912, 58ff, 241ff.

For a brief review of Einhard's career, see von Schubert, 1921,

742-43. Einhard was a lay abbot, and does not seem to have received

even the lower orders. That he, only an abbot, could not have used the

address dulcissime fili to another person of the same rank had already been

pointed out by Digot (1853, 128). To this argument I have added the

observation that the standard formula used by Einhard in addressing

other abbots always ended with the words "Einhard the Sinner"

(Horn, in Studien, 1962, 107, note 21). The collection of Einhard's letters

(by Hampe in Mon. Germ. Hist., Ep. V, 1899, 105-45) contains one

letter addressed to Abbot Gozbert of St. Gall (ibid., 129, No. 39). Its

opening line reads: "Religioso Christi famulo Gozberto venerabili Abbati

E[hinhartas] P[eccator]." This has a ring quite different from the

dulcissime fili of the author of the transmittal note of the Plan of St. Gall.

For a more complete account on Einhard, see the works discussed by

Francois L. Ganshof, 1924.

See Gesta abbatum Fontanellensium; ed. Loenwenfeld, 1886, 49; and

the more recent edition of Lohier-Laporte, Gesta SS. Patr. Font. Coenobii,

1936, 92ff. Ansegis, born around 770, entered the monastery of St.Wandrille

at the time of Abbot Geroaldus (787-806), a relative of his,

who introduced him to the palace ("Denique, tenente locum regiminis huius

coenobii Geroaldo abbate, propinquo suo, hoc accessit monasterium tonsuramque

capitis ab eo suscipit. Denique non multo post ad palatium eum perducens,

in manus gloriosissimi regis Karoli commendare studuit.") For further information

on Abbot Ansegis, see the article by P. Fournier, "Anségise," in

DHGE, III, 1914, cols. 447-48 and the translation of the Constitution of

Ansegis by Charles W. Jones, III, Addendum II, 125.

See Gesta episcoporum Tullensium; ed. Waitz, VIII, 1848, 637, and

the article "Frothaire," in Chevalier, I, 1905, col. 1621.

Dopsch's suggestion of "Gozbert's aged teacher, Reginbertus of

Reichenau" has been convincingly refuted, in my opinion, by Beyerle

(1925, 82), who proved that there is no evidence that Gozbert received his

training at the school of Reichenau. While it is conceivable—although

perhaps not very likely—that a teacher, as pater spiritualis (a possibility

that Father Iso Müller had brought to the attention of the International

Symposium at St. Gall in 1957), might continue to use the address

dulcissime fili even after his former pupil had risen to the rank of abbot,

this would be applicable to Reginbertus of Reichenau only, of course, if

it could be established that Gozbert had been his pupil.

I. 5

THE EXPLANATORY LEGENDS

AND THE SCRIPTORIAL HOME OF

THE PLAN

I.5.1

DISTINCTION BETWEEN GENERAL

AND SPECIFIC TITLES

Apart from the transmittal note discussed above, the

explanatory legends of the Plan consist of 340 titles of

varying length which describe the purpose of each building,

the function of the individual rooms, as well as the equipment

and furnishings therein. The general purpose of each

building, as a rule, is described in a verse (hexameter or

distich), written parallel to and at a small distance from the

entrance wall of the house to which it pertains. The titles

that define the internal functions of each building are

written in prose.[87]

They are always inscribed in the center

of the area they describe or as close to the center of that

area as conditions permit. Exceptions to this are made in

only a few cases, where the object is too small to accommodate

its title, such as the cupboards (toregmata) in the

dining hall of the House for Distinguished Guests (fig.

396),[88]

the abbot's living room (fig. 251),[89]

and the Monks'

Refectory (fig. 211).[90]

I must stress this point, since Bischoff's remark that in a great many

cases the verses "simply synthesize or paraphrase the significance of an

individual structure without adding anything new to what may be

gathered more clearly from the prose inscriptions" is misleading

(Bischoff, in Studien, 1962, 74). For the majority of buildings supplied

with metrical legends this is distinctly not the case. I cite as a typical

example the inscriptions of the House of Distinguished Guests: the

general purpose of this house is expressed in a hexameter that runs

parallel to the entrance side of the building, Haec domus hospitibus parta

est quoque suscipiendis. The verse explains the general purpose of this

structure and could be simply translated: "This, too, is a house for

guests" ("too," in contradistinction to the Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupers). This general definition is not repeated in any of the prose

titles entered in the interior of the structure, all of which designate the

purpose of individual rooms, or the nature of an individual piece of

furniture in these rooms.

Bischoff's unawareness of the difference between the general (metrical)

and specific (prose) titles may have been occasioned by the untraditional

use of the term domus, which on the Plan of St. Gall is never used to

designate the whole of a house (its classical and traditional meaning),

but always refers to the large central hall in the interior of the house

which contains the hearth and serves as general living room (for further

details, see II, 77, and III, Glossary, s.v.

I.5.2

TWO HANDS REPRESENTING TWO

STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT IN THE

SCRIPTORIUM OF REICHENAU

A careful paleographical analysis by Bernhard Bischoff

of the textual annotations of the Plan established the

monastery of Reichenau as the scriptorial home of the

Plan.[91]

Bischoff distinguishes two hands, working in close

co-operation but representing two different developmental

stages of writing within the scriptorium of the abbey of

Reichenau: that of a younger man, the "main scribe,"

who is responsible for 265 of the 340 entries, and that of an

older man, the "second scribe," who wrote the remainder.

The main scribe rendered his legends in a deep-brown

ink almost bordering on black. He wrote in a small, crisp,

and finely articulated Carolingian minuscule, making use

of relatively closely spaced and nearly perpendicular

letters with long ascenders.[92]

This scribe is also responsible

for the letter of transmittal on the upper margin of the Plan

(fig. 2) and for ten legends written in capitalis rustica.[93]

The second scribe rendered his legends in a pale-brown

ink. He wrote a minuscule of more rigid perpendicularity,

spacing his letters a little farther apart and using shorter

ascenders. The entries of this scribe are confined to the

designations of the trees and plants in the two monastic

gardens (figs. 414 and 426),[94]

the names of the trees in the

Cemetery (fig. 430),[95]

the titles of the ten altars in the aisles

of the Church (fig. 93),[96]

the titles for the altars in the

Church towers;[97]

as well as some lines which look like

additions, such as the supra camera et solarium in the

Abbot's House (fig. 251),[98]

the infra supra tabulatum in the

House for Horses and Oxen (fig. 3),[99]

and the first three

lines of the verse that identifies the function of the Porch

connecting the western paradise of the Church with the

grounds of the House for Distinguished Guests (fig. 4).[100]

Bischoff was able to identify the hand of the main scribe

as that of a monk who, at an earlier stage of his career,

wrote a Vita sancti Bonifatii on fols. 2v-19 (fig. 5) of a

hagiographical ms. (Karlsruhe, Codex Augiensis CXXXVI)

written in the monastery of Reichenau under the direction

of its erudite librarian, Reginbert. His script suggests that

he is a younger man, whose style of writing has been

influenced by a temporary sojourn in Fulda.[101]

5. VITA SANCTI BONIFATII. KARLSRUHE, BADISGHE LANDESBIBLIOTHEK. Codex Augiensis CXXXVI, fol. 14v

Script written by main scribe of the Plan of St. Gall (courtesy of the Badische Landesbibliothek, Karlsruhe). Illustration enlarged 1.07 ×.

The script of the second scribe is that of an older man,

and its basic paleographical features are so similar to those

of Reginbert himself—the last among the classical Carolingian

writers to use this type of script (he died in 846)—that

Bischoff feels it might well be the product of Reginbert's

own hand.[102]

From the nature of his textual entries, which

have the appearance of what Bischoff calls "katalogartige

Nachträge," Bischoff infers that the second hand acted in

a supervisory capacity, filling in and completing where the

knowledge of the main scribe ended. Contrary to this

general relationship, however, there is one entry—the

legend that defines the function of the Porch connecting

the western paradise of the Church with the grounds of the

House for Distinguished Guests—in which the first three

lines are written in the ductus and pale-brown ink of the

"supervising" hand (the hexameter, Exi & hic hospes uel

templi tecta subibit), whereas the three lines that complete

this verse are written in the style and dark-brown ink of

the main hand (the pentameter, Discentis scolae pulchra

iuuenta simul). The co-operation between the main scribe

and the supervising scribe, Bischoff infers from this, must

have been extremely close.

See Bischoff, in Studien, 1962, 67-78; and reprint of this study in

Bischoff, Mittelalterliche Studien, I 1966, 41-49.

One in the road that gives access to the Church, five in the Church

itself, one in the church of the Novitiate and the Infirmary, one in

the Monks' Vegetable Garden, one in the Goosehouse and one in the

Henhouse.

Ibid., 73, note 16: ". . . die Identität des `alemannischen' Schreibers,

der die Arbeit leitete . . . mit Reginbert möchte ich für wahrscheinlich

halten, ohne sie jedoch für bewiesen anzusehen."

I.5.3

CONCEPT OF AUTHORSHIP & HAITO

To what extent do Bischoff's findings on the paleographical

nature of the explanatory titles of the Plan confirm

or contradict our theory of Haito's authorship?

They make one point quite clear: Haito cannot have been

identical with the scribe who wrote the letter of transmittal

and the majority of the other titles of the Plan. At the time

the Plan was made, Haito was not a young man. He was

already around fifty-eight years of age in 820.[103]

These

findings, however, do not in my opinion disqualify Haito

from the authorship of the Plan. The concept of authorship

in the Middle Ages is complex. Bischoff himself furnishes

us with an excellent case in point. The above-mentioned

Codex Augiensis CXXXVI contains on folio IV an annotation

in which Reginbert of Reichenau refers to himself in

unequivocal terms as the "fabricator" of the book, "Hunc

libellum . . . meo studio confeci." Yet besides this entry on

folio IV, some chapter headings on folios 21r, 24r, and 28r,

and some isolated corrections here and there, no other line

of this work is written in his own hand.[104]

It is not necessary, with this concept of authorship, to

expect that the person who in the transmittal note of the

Plan defines himself as its maker should actually have

traced the Plan or written its explanatory titles. He is the

person who directed that the Plan be made, and who—

once it was made—transmitted it to the person by whom

it had been requested.

Bischoff has established that the explanatory titles of the

Plan were written in the monastery of Reichenau, perhaps

under the supervision of Reginbert, with the assistance of

a scribe who had co-operated with Reginbert in other

literary endeavors. Reginbert is not a likely candidate for

the authorship of the Plan for reasons that I have stated in

the preceding chapter. This leaves, once more, as the only

logical choice, Bishop Haito of Basel who, as the superior

of the two, might very well have availed himself of their

joint support in making the Plan.

As one of the leading bishops and abbots in the empire,

Haito is furthermore a person who can be expected to have

had access to the prototype plan.

I. 6

ORIGINAL OR COPY?

I.6.1

SOME TECHNICAL OBSERVATIONS

That the Plan of St. Gall is a "copy" rather than an

"original" must be inferred not only from the fact that its

maker refers to it as exemplata, i.e., "transcribed" or

"copied," but also from a variety of observations of a

technical nature, on which I have reported in a previous

study.[105]

A careful examination of the particulars of the

design of the Plan shows that it was traced, like a modern

"overlay," on pieces of parchment that were superimposed

upon a prototype plan. This is revealed by the following

facts:

1. The Plan does not show any underdrawing, as

would be inevitable in a layout of this complexity if it were

an original design.

2. The Plan exhibits in several places angular distortions

in the alignment of rectangular structures which are

characteristic of the displacement that occurs in tracing if

in the course of work the overlay inadvertently shifts a

few degrees from its initial alignment with the original and

this shift is not immediately corrected.

3. The drawing is full of minor inaccuracies and inconsistencies

that appear to be incompatible with the

exacting calculations prerequisite to the development of an

architectural drawing of this complexity; and it is rendered

in a fluid style not apt to be found in the work of a man

who went through the developmental labor of this demanding

task.

In what follows I shall elaborate on these observations.

ABSENCE OF UNDERDRAWING

In figure 6, I have reproduced a detail of a well-known

architectural drawing of the thirteenth century which

renders the ground floor of the southern tower of Cologne

Cathedral.[106]

This design, which is a typical example of its

kind, shows how in laying out his plan a medieval architect

avails himself of an elaborate framework of auxiliary construction

lines and reference points which he presses into

the parchment with a fine stylus or silverpoint before

committing his drawing to ink. This constructional reference

work guides his eye as the drawing is being executed

and remains visible as an underdrawing, in the form of

thin grooves and fine prickings,[107]

in those portions of the

design which are not covered by ink in the final stage of the

work.[108]

In contrast to this, on the entire Plan of St. Gall there is VIENNA, AKADEMIE DER BILDENDEN KÜNSTE, KUPFERSTICHKABINET Plan of buttressed pier in the southwest tower of Cologne Cathedral.

not a single line of this type to be found.[109]

The absence of

such auxiliary construction work is most conspicuous in

6. ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING: DETAIL, FACSIMILE

13th century

The drawing of which this detail is a part measures 700 × 610 mm.

See comments for figure 9.

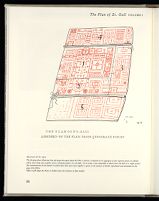

7. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Alignment of Outer School, House for Distinguished Guests, and

Kitchen, Bake, and Brew House for Distinguished Guests. The

superimposed black lines show which course the outer walls of buildings

would have taken had they been drawn with instruments. The largest

departure from parallelism at the end of lines running askew because of

inaccuracies incurred in tracing are 4 mm at the bottom of fig. 7 and

6 mm at the top of fig. 8.

and double rows, or in the interior of buildings whose

layout is so complex that it could not have been drawn

without a linear frame of reference. This can be illustrated

by some typical examples.

Reproduced with the kind permission of Professor Siegfried Freiberg

of the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna. For a reproduction of

the entire drawing (No. 16.873 of the Kupferstichkabinett der Akademie

der Bildenden Künste) see Hans Tietze, 1931, 169. Misinterpreted by

Tietze in several respects, the plan was thoroughly rediscussed and reevaluated

by Hans Kauffmann, 1948, 80-88.

These fine prickings are not so easily detected on photographs as on

the original. Two typical examples, not discernible in the reproductions

shown in figure 6, are indicated by arrows.

In an earlier stage of my studies (Horn, ibid., 82-83) I expressed the

thought that a shaded ridge that runs in the axis of the southern nave

arcade (most clearly visible in interstice of the first two columns, counting

from west, and in its prolongation of their axis through the western

paradise) might have served as a base line to fall back on in case the two

skins should shift in the course of tracing; but the fact that this line

(not drawn with the aid of a stylus, but more likely the result of a

deliberate folding and restretching of sheet 2 before it was attached to

sheet 1; cf. below, 35ff) coincides with the deflected rather than the

original axis of the Church discredits this view.

ABSENCE OF GUIDING CONSTRUCTION LINES

IN THE ALIGNMENT OF BUILDINGS

Reproduced in figure 7 is a portion of the building site

to the north of the Church, showing (from top to bottom)

the western end of the Outer School, the House for Distinguished

Guests, and the Kitchen, Bake, and Brew

House for Distinguished Guests. Examination of the open

spaces between these structures shows that the parchment

here has never been touched by a stylus. This had noticeable

consequences for the style of these drawings: the walls

that form the outer boundaries of these houses do not stay

"in line," most drastically so in the case of the Kitchen,

Bake, and Brew House, whose southern gable wall slants

away from its proper alignment by an angle of two degrees.

If the parchment surface had been provided with guiding

construction lines, the draftsman's hand could never have

slipped away from its regular course as far as it did when

drawing the southern walls of the Kitchen and Bake House,

converting a building that was of rectangular shape into a

trapezoid structure.

An even more flagrant case of the divergence of lines

meant to run parallel to one another is to be found on the

opposite side of the Plan in the alignment of the three

buildings that contain the Mill, the Mortar, and the Drying

Kiln (fig. 8). This kind of linear aberration might easily

occur in the process of copying when the translucency of

the skin on which the Plan was being traced was temporarily

marred by changing light conditions, but would be unlikely

to occur on an original where the quill of the draftsman

followed the grooves of a constructional underdrawing.

On the Plan of St. Gall such grooves can be discovered

neither on the recto in the form of the familiar furrows nor

on the verso in the form of thin ridges. Throughout the

entire expanse of the Plan, with its total of forty separate

structures of varying size, no trace is to be discovered of

any underdrawing that would have enabled the architect

to fix the dimensions of an individual structure within the

aggregate of its superordinate building site, or the boundaries

of the individual building site within the layout of the

entire Plan. Yet it is obvious that even the most accomplished

architectural draftsman could not assemble such a

variety of different structures into an over-all design of

such complexity without the aid of a guiding underdrawing.

In the absence of underdrawing, the design can only have

been produced by tracing.

Parchment, because of its relative opacity, is not an ideal

medium for tracing; but designs can be traced directly

from one sheet of parchment to another, as may be established

easily by experimentation in any library that is

provided with scraps of medieval manuscripts.[110]

It cannot be done easily if the two skins are laid flat upon the surface

of a dark table, but can be accomplished without difficulty if they are

held against a windowpane or against a lighted surface reflecting the sun

in sufficient strength to project the design of the original through the

transparent body of the skin above it on which the design is to be redrawn.

I am most grateful to Dr. Johannes Duft for helping me to

establish this fact by superimposing sheets of medieval parchment of

varying thickness from the archives of the monastery of St. Gall and

observing their translucency under different light conditions. To produce

a tracing from an original of some 30½ × 44 inches is nevertheless not an

easy task, even though the tracing was done on three separate sheets. In

order to keep the original under sufficient tension to provide a solid base

for the hand of the copying draftsman and to permit him to move it in

the direction of the required light, it must have been mounted on a

wooden frame. To a medieval scribe the mounting and stretching of

skins on wooden frames was a familiar practice, as it was a standard

procedure in the manufacture of parchment.

(Since these lines were written I have had occasion to experiment

with recently manufactured sheets of parchment, and have been able to

infer from this that fresh parchment is considerably more translucent than

parchment yellowed by age. If the sheets on which the Plan of St. Gall

is drawn were at the time of their manufacture as white and translucent

as modern pieces of parchment of the same thickness, the tracing could

have been produced on a table.)

ABSENCE OF GUIDING UNDERDRAWING IN THE

INTERNAL LAYOUT OF INDIVIDUAL BUILDINGS

An examination of the procedure followed in the construction

of the internal layout of the various buildings leads us

to the same conclusions. No building illustrates this fact

more persuasively than the Monks' Dormitory.

The Dormitory of the monks (fig. 60.A) accommodates a

total of seventy-seven beds. These are arranged in a

complicated pattern, resembling the letter U along the

two side walls, and the letter H (the U-pattern of the side

walls coupled) along the center of the building. One does

not have to look twice at this complex arrangement to

realize that it is impossible to distribute seventy-seven beds

in the manner just described within an area of such small

dimensions without a carefully calculated underdrawing.

Yet intricate as this layout is, the basic frame of reference

from which it was developed was ingeniously simple. It

consisted, most likely, of a simple grid of squares of the

type that I have reconstructed in figure 60.B, making use of

a measurement that serves as a basic unit value throughout

the entire Plan. In the development of the primary design

for such a layout, which must have been worked out before

the building was inked onto the original plan, such a

square grid may have been pressed into the parchment in

full detail. As the design was transferred to the master

sheet in the final assembly, there was no need to retrace

the square grid in its entirety, but a minimum of auxiliary

co-ordinates and prickings must, nevertheless, have been

laid down to enable the draftsman to fix the width and

length of each bed and to enter it in its proper place. Yet

nowhere in the interstices between the beds, on the Plan

of St. Gall, is there the slightest trace of such auxiliary

construction work. It is omitted from the internal layout of

the buildings shown on the Plan, and absent as well from

their external alignment.

8. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Alignment of Mill, Mortar, and Drying Kiln

9. ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING: DETAIL, FACSIMILE

13th century

[courtesy of Vienna Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Kupferstichkabinet]

The spiral depicting the stairwell in the southwest tower of Cologne

Cathedral was constructed with compass and straightedge against a

framework of auxiliary lines and reference points pressed into the

parchment with a fine stylus or silverpoint before the drawing was

inked—a procedure wholly different from the manner in which the

Plan of St. Gall was drawn. The only freehand parts of this drawing

are those which because of their intricacy of design were not feasible

to draw otherwise.

Figures 6 and 9 are details of the same drawing and are reproduced in this work

at the same size exactly as they were drawn on the original. Drafting at this scale of

fine detail is essentially a freehand operation.

ABSENCE OF CENTER POINTS IN THE

CONSTRUCTION OF CIRCLES

To construct a circle accurately, one must firmly anchor the

center leg of the compass in the material on which the

circle is to be drawn. The point of this leg has to penetrate

deeply enough to stay in place while the outer leg strikes

the circle. This is bound to leave a mark in the parchment,

and for this reason, on all medieval architectural drawings

on which circles have been drawn with the aid of a compass,

there is always a clearly visible depression or minute hole

in the skin, which reveals the point from which the circle

was struck. I refer once again to the drawing of the southwestern

tower of Cologne Cathedral as a typical case. It

contains two circular installations, a spiral stairwell built

into the masonry of the southwestern corner pier (fig. 9)

and a circular opening in the vault of one of the two inner

bays of the tower (the latter not reproduced here). In both

instances the hole that the center leg of the compass left in

the parchment as the circle was struck appears as a small

but clearly perceptible mark.

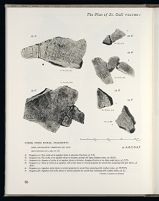

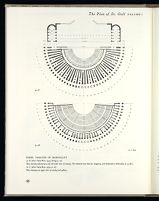

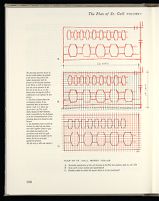

For purposes of comparison, five circular installations

shown on the Plan of St. Gall are reproduced in figures

10-13. Figures 10.A-B are the ambo and the baptismal font

in the nave of the church; figures 11.A-B are the two

circular towers that flank the Church to the west. Figure 12

is the enclosure for the hens to the south of the House of

the Fowlkeepers. No trace of the center point is found in

any of these drawings. Furthermore, these circles are too

inaccurate to have been constructed with the aid of a

compass. A circle drawn by compass forms a continuous

line of equal thickness, all points of which are equidistant

from the center point, as is well illustrated by the circle

that forms the outer boundary of the stairwell of Cologne

Cathedral. The circles reproduced in figures 12-13, on

the other hand, are drawn in successive motions of the

rotating hand, the beginning and end of which can still

be identified in many cases. Thus, for instance, close

inspection of the Plan of St. Gall shows that the outer

circle of the Henhouse (fig. 12) was drawn in five separate

with a leftward motion and continued counter-clockwise

in four successive strokes, as I have indicated in figure 13.

As the draftsman passed through this course, he must

have rotated the two skins on which he worked in a

clockwise motion, a procedure which he repeated when

he entered the large explanatory title enclosed by the

circle that identifies this structure as the Henhouse. As he

approached the close of the circle, the draftsman discovered

that his terminal stroke was not in alignment with his

opening stroke, corrected this discrepancy with an additional

stroke which ran parallel to the first, but about 1 mm.

farther out.

While the circles are neither continuous nor accurate

enough to have been drawn by compass, they are far too

accurate to have been drawn without auxiliary construction

lines. As no such lines are to be discovered, we are once

were traced directly from an underlying original.

ANGULAR DISTORTIONS CAUSED

BY A SHIFT IN THE RELATIVE POSITION OF

ORIGINAL AND OVERLAY

My second argument in support of the contention that the

Plan of St. Gall is not an original rests on the observation

that in several areas the drawing exhibits angular distortions

that owe their origin to a shift in the alignment of original

and overlay. This observation is of crucial importance not

only for the question of originality but also because it gives

us a clue for establishing the sequence in which the buildings

were traced. We shall analyze this phenomenon in

detail in a subsequent chapter.[112]

For the present discussion,

suffice it to stress that we are faced here with a type of

linear deflection caused in the process of tracing when an

inadvertent shift between original and overlay is not

immediately detected and corrected. These deflections are

unlikely to occur on an original, as the underdrawing

would contain each individual building within the area

assigned to it, and would prevent the parallels from running

askew. The author of the Plan of St. Gall was able to

dispense with an elaborate system of auxiliary reference