The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. | III |

| III. 1. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

III

THE CLOISTERS AND

THE ABBOT'S HOUSE

III. 1

THE CLOISTER OF THE MONKS

(III.1.1)

LAYOUT

IN proposing that a monastery should "be so arranged that all necessary things, such as water, mill, garden, and

various crafts may be within the enclosure,"[1]

St. Benedict made the monastery economically independent of the

secular world. The administration of the self-sufficient estates which emerged from this concept, however, brought

into the monastic community a host of seculars, whose very presence threatened to subvert the monastic ideal of

seclusion from the world and its preoccupations. As the monastery came structurally to resemble a large manorial

estate, monastic integrity demanded the creation of an inner enclosure that would isolate the brothers from the serfs

and the laymen and, at the same time, make it possible for the latter to live as close to the brothers as their tasks

required. Creating a cloister answered this problem. It established a monastery within the monastery. Moreover

in meeting the complex needs of monastic living, it created an architectural scheme that added to the glorious

history of the colonnaded classical court a new, and perhaps its most accomplished, embodiment.

The cloister is the monastic enclosure which serves as living, eating, working, and sleeping quarters for the monks

(figs. 191, 192, 193).[2]

In its fully developed form it consists of a large square yard attached to the southern flank of

the church, entirely surrounded by a covered walk, and enclosed on the three other sides by a solid range of large

(usually double-storied) structures laid out so as to form a solid architectural enclosure. This ensemble of buildings

comprises, in addition to the dormitory and refectory of the monks, a warming room, a cellar, a larder, a storeroom

for the monks' clothing, and various smaller dependencies, such as a privy, a bath and wash house, a kitchen, and a

bake and brew house. Except for the times when he worked the fields or helped to reap the harvest, or those rare

occasions when he was away on journeys, the entire life of the monk was spent in this enclosure.

The origin of the layout of this well-ordered and symmetrical architectural scheme is as yet not clarified, since

many of the intermediary forms of its development are missing.[3]

It has been connected with the peristyle court of

the Greek house, the colonnaded atrium of the Roman house, the monumental galleried atria of the large Early

Christian churches, and certain semi-galleried courts attached to the flanks of Syrian churches. In one way or

another, all these forms may have shared in its formation.

It is obvious that the concept of an open galleried court with living units around it, is a Mediterranean one. The

ubiquitous character of this motif in the Greek and Roman world needs no further comment. It is equally clear that

the concept of double-storied masonry structures, exhibited in the primary claustral structures (Dormitory,

Refectory, and Cellar) has its roots in Rome, and not in the vernacular architectural tradition of the Franks. The

consummate order and symmetry characterizing the claustral scheme was, in its ultimate form, classical and had

little to do with the scattered layout of the contemporary northern manor. But after full allowance is made for these

classical influences, it is equally clear that nothing quite like the layout of a medieval cloister existed in antiquity.

The medieval cloister differs from the Hellenistic peristyle and the colonnaded Roman atrium in that it is not a

court enclosed by a dwelling, but rather an aggregate of edifices, so arranged as to form a solid architectural frame

around a court. From the atria of the large Early Christian basilicas, to which it is related in design and in size, it

differs in function. The Early Christian atrium was a large formal plaza for the reception of the worshiping crowd;

it was never meant to form the nucleus of a cadre of dwellings. In Syria here and there we find monastic courts

attached to the flanks of the church—and these courts may indeed be one of the germinal prototype forms of the

medieval claustrum—but unlike the later medieval cloister, in Syrian monasteries the open courts were in general

not enclosed by buildings on all four sides. Often these courts were not even square, but L-shaped, or of irregular,

and undefinable shape, with vast openings between the houses of the monks giving free access to other segments

of the monastery grounds. There are, nonetheless, two notable exceptions: the convent of SS. Sergios and

Bacchos at Umm-is-Surab and the convent of Id-Dêr, both in Southern Syria. In the former (fig. 193) the monas-

court in the middle "colonnaded on all sides in two stories and completely surrounded by rooms, large and small,

in one or two stories, about twenty in all, forming an ideal monastic establishment."[5] In the latter (fig. 194) also of

fifth century date, the church had in front of it a great open atrium, with colonnaded apartments in two stories

symmetrically ranged around three sides of the court, plus a connecting colonnaded porch along the facade of the

church.

Although there is no tangible archaeological evidence to support such a conjecture, it is entirely possible that

together with the more common open plan of the Syrian cloister, the closed and highly symmetrical schemes of

Umm-is-Surab and of Id-Dêr may also have found their way into Western Europe. If they did, however, these

schemes would have found themselves in oppressive competition with the infinitely more common lavra system

adopted by the monks of Lerins, and diffused throughout the entire pre-Carolingian West by the Irish mission

which professed to the same ideals of anchoritic withdrawal and individualistic piety. To combat, repress, and

eventually wholly supersede this powerful tradition depended on the rejection of the scattered and semi-hermitic

forms of living of the Irish monks in favor of the highly controlled and ordered form of communal living prescribed

by St. Benedict. The evolution of this concept required first and above all that the formerly scattered

houses of the monks be brought together into an ordered architectural system, which in turn could be merged with

the concept of the colonnaded classical court. The creation of a tightly closed monastic range of buildings, however,

was only a part of the total need. The same ordering genius that led to the invention of an inner enclosure for the

monks was also to be applied to the layout for the cloisters of the novices and the sick, as well as to the problem of

meaningful interrelation of these three nuclear monastic blocks with the other indispensable monastic installations:

facilities for the reception of visitors, houses and workshops for the craftsman and serfs, and houses for

the monastic livestock and their keepers.

It is possible that the ultimate crystallization of this scheme does not antedate the reign of Charlemagne. Its

adoption depended on the abolishment, through binding acts of legislation, of the mixed forms of monastic living

that prevailed in pre-Carolingian times, and their replacement by the single, exclusive and universally binding

rule of St. Benedict. This striving toward uniformity of custom had been from the outset a prime objective of the

ecclesiastical policy of Charlemagne. It became again, under Louis the Pious an overriding goal of the monastic

movement, as evidenced in the legislation issued at the two synods held at Aachen in 816 and 817. To presume,

however, that the "Plan of an ideal City for Monks" that emerged from these efforts was a product wholly of

the Carolingian reform movement may be stretching the point. The individual elements and many of their combinations

are of a considerably earlier date, but the consummate order of the scheme, its binding perfection that was

to affect the entire future course of monastic planning may have been dependent on the codification of certain details

in the relation of monks to serfs, which was not undertaken prior to the two synods of Aachen.[6]

The novelty of this concept is thrown into full relief when it is compared to the monastic settlements which

the Irish holy men established during the sixth and seventh centuries in relatively inaccessible and often hostile

places of Ireland and western England.

Benedicti regula, chap. 66; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 156; ed. McCann, 1952,

152-53; ed. Steidle, 1952, 320.

It is clearly defined as such by Hildemar of Corbie (845-850):

"Notandum est quia talis debet esse claustra monasterii, ubi monachus ea

quae necessaria sunt valeat exercere, id est consuere, lectioni vacare et rel., et

ubi custodia possit esse." (Hildemari Expositio regulae; ed. Mittermüller,

1880, 613).

A comprehensive treatment of the architectural remains of Early

Christian monasteries in the Near East does not exist. For summary

reviews see Bernheimer, 1939, 660ff, and Sowers, 1951, 128-86; for a

discussion of individual buildings: Voguë, 1865-1277, passim; Butler,

1929, passim, and Tchalenko, I, 1953, 145-82.

Since this chapter was written, I have dealt with the question of the

origins of the medieval cloister more extensively in three articles (see

Bibliography, Horn 1973, 1974 and below, p. 245 n7).

See in particular my remarks on the transfer of houses for the workmen

and craftsmen from an extramural to an intramural location as

directed in chap. 5 of the first synod, and Bishop Haito's commentary

thereto; above, p. 23.

III.1.2

THE "SCATTERED" PLAN OF THE

EARLY IRISH MONASTERIES

These early Irish monasteries were usually set up in a

circular or ovoid enclosure surrounded by a wall of stone

or earth with a ditch outside—not very different in appearance

from the old Iron Age ring forts (the so-called

cashels) many of which in fact appear to have been taken

over by the Irish missionaries and converted into monastery

sites.[7]

Within such an enclosure there was a church, in

general of very modest dimensions, and loosely scattered

around it, without any fixed architectural order, the beehive

huts for the monks, as a rule inhabited by two,

occasionally by more—as well as a place for eating, a guest

house, a kitchen, and a school.

When the community outgrew the size of its original

church, rather than replacing it by a new and larger one,

the monks added another church and yet another one if

further growth demanded it. Since the majority of these

buildings were constructed in timber, they have left no

visual record whatsoever; and if it were not for the fact that

on the isolated and wind-swept islands off the west coast of

Ireland trees and thatch were not available, the monks

thereby being forced to build in stone, we would live in

total ignorance of the layout of these early monastery sites.

The best preserved among these stone-built monasteries is

the cashel of Inishmurray Island, off the Sligo coast (fig.

195). It consisted of an egg-shaped enclosure measuring

internally about 175 feet in length and 135 feet in breadth,

The enclosure was formed by a dry-built masonry wall that

varied at its base in thickness from 7 to 15 feet and rose to a

height of well over 13 feet. It shelters the remains of three

rectangular oratories of modest size, a circular school house

and two beehive huts. To complete the original appearance

of this settlement, one would have to add to the reconstruction

shown in figure 195 a few more dwellings for monks as

well as buildings indispensable for community use, such as

a refectory and a kitchen, which have left no trace on the

site.

Monasteries of this type—or to be more precise, their

timbered equivalents—must have been a common sight in

sixth- and seventh-century Ireland and England as well as

at all of those places on the continent where Irish missionaries

established new monastic communities. It must

have been that same type of settlement with monastic

dwellings loosely dispersed around an oratory that St.

Columban and St. Gall had founded at the upper end of

Lake Constance and that sprang up in the wilderness of the

upper Steinbach river, where after Columban's departure

for Italy, St. Gall had formed a cell that in the centuries to

follow was to become one of the greatest Carolingian

monasteries.

Irish monasticism, like that of the Egyptian and Syrian

monks of the desert after which it was modelled, was based

upon the concept of individual self-discipline of holy men

living either as hermits or in loosely connected groups. The

architectural layout of the Irish monastery mirrors this fact

as clearly as the ordered architectural enclosure of the

Benedictine monastery reflects the highly organized community

life established by the Rule of St. Benedict.

On Irish monasticism and early monastic settlements see Leask, I,

1955, 5ff and Paor, 1958, 49ff.

III.1.3

FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE SQUARE

CLOISTER

Precisely at what time it became customary that the

cloister yard should assume the form of a galleried square,

attached on one side to the flank of the church and on the

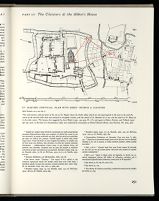

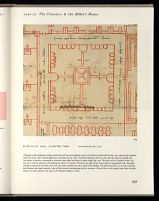

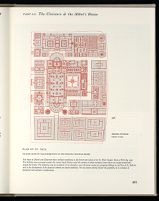

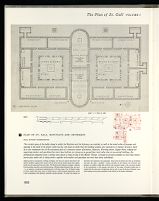

192. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PRINCIPAL CLAUSTRAL STRUCTURES & THE MONKS' CLOISTER

Cutaway Perspective. Authors' Interpretation

Three double-storied masonry buildings solidly enclosing an open yard are attached to the southern flank of the Church, and are connected at ground level by the covered

arcaded walks of the cloister. The east structure contains the Warming Room, below, and the Monks' Dormitory, above. From its southern gable wall an exit leads to

the Monks' Privy on the upper level, and at ground level another leads to their Laundry and Bathhouse. The south structure contains on ground level the Monks'

Refectory and above it their Vestiary. From its western gable wall an exit leads to the Monks' Kitchen at ground level. The west structure contains on ground level

the cellar, and above it, the Larder.

On the Plan itself (fig. 191), although the Dormitory layout is actually drawn on ground level, an inscription makes clear that it is to be located in the second story.

The Plan does not show any stairs between floors. We make no attempt here to correct this shortcoming by supplying features to which the designer himself chose to make

no committment. By suppressing stairs he not only was able to keep his design uncluttered, but also emphasized that wherever, in the process of construction, stairs were

to be installed they should be located so as not to interfere with arrangements which he considered to be of more vital concern: Dormitory bed layout, Refectory bench

and table layout, Cellar barrel layout—all worked out with great care, in full consideration of the number of monks to be served by these respective structures, and the

volume of wine and beer to be stored (see below: Dormitory, pp. 250, 342; Refectory, p. 286 and Fig. 211; Cellar, pp. 296-303).

Not disregard, but rather a choice between details of primary and secondary importance, induced the designer to suppress stairs. In so choosing he arrived with depth

of technical insight and wise restraint at a solution, at once ingeniously simple and equally sophisticated, to the special task facing him: namely, assembling on a single

drafted plan all essential information needed to construct the forty-odd buildings of which a paradigmatic monastery of his period was to be composed.

is impossible to say in view of our almost total

ignorance about the layout of transalpine monasteries in the

critical period of transition from the Irish to the Roman

Benedictine rule.[8] The cloister of the famous Abbey of St.

Riquier, built under Abbot Angilbert from 790-799 (figs.

196-197),[9] had the shape of an obtuse triangle which shows

that even late in the eighth century the square had as yet

not been established as an obligatory form. Its dimensions

likewise are far from conforming to any recognizable

standards; for the longer side of this triangle had the extraordinary

length of 984 feet, the two shorter ones of 705 feet

and 525 feet.[10]

An early transalpine case of a square-shaped cloister,

by contrast, is the early Carolingian monastery of Lorsch

between 760-774.[12] The buildings of this settlement, as

its excavator Friedrich Behn points out, were not a new

creation but a conversion to monastic use of the villa of a

Frankish nobleman, laid out in the tradition of the Roman

villa rustica. Its galleried court formed a square of approximately

70 × 75 feet, and hence was considerably

larger than the atrium of the average Roman villa rustica.

Contrary to later monastic preference the church was

located along the southern side of the court, presumably

for special topographical reasons, namely because on this

side the monastery bordered on an ancient Roman road.

The east side and the west side of the square were taken

up by two oblong buildings, corresponding to the later

dormitory and cellar. The north side, as in most of the

Roman prototype villas, was only closed in by the galleried

porch that formed the northern cloister walk.

That a Frankish farmhouse, built in the Roman tradition,

could be converted into a Benedictine monastery

without substantial alterations bears witness to the close

conceptual relationship of the Carolingian cloister plan

with that of the Roman villa rustica. The countryside of the

former Roman provinces of Germany and Gaul abounded

with such buildings and many of these may still have been

in use during the early Carolingian period.

When the monastery of Lorsch was rebuilt on higher

ground on a neighboring site between 784 and 804 (figs.

southern flank of the new church, and masonry buildings

were placed peripherally around the three remaining sides

of the yard. This is the form that was chosen by the author

of the layout of the paradigmatic monastery shown on the

Plan of St. Gall. Richbold's monastery of Lorsch shares

with the layout of the latter another important feature. Its

cloister measures 100 by 100 Carolingian feet (34 m. by

34 m.), proportions which in the ninth century appear to

have acquired an almost canonical value.

As we are talking about the conceptual relationship between

the layout of a square-shaped monastic cloister range

with a galleried court and that of the Roman villa rustica,

we must not lose sight of another possibility heretofore

overlooked, namely, the likelihood of an influence from the

ruins of judiciary Roman basilicas. Many of these had

attached to one of their long sides a galleried court of considerable

size completely surrounded by shops. A double-apsed

basilica of this type was excavated around 1880 by

J. G. Joyce, in the Romano-British city of Silchester (fig.

202), and another one more recently in the Gallo-Roman

city of Augst, in Switzerland.[15]

The type must have been

very common in the transalpine provinces of Rome, and

their remains may still have been visible in many parts of

the empire at the time of Charlemagne.

Since this chapter was written, I have dealt with the question of the

first appearance of the square or U-shaped cloister in the article, "On

the Origins of the Medieval Cloister," Gesta XII (1973), 13-52. The

conclusions offered state that despite the sporadic appearance of four-cornered

cloisters in certain Early Christian monasteries of Syria

(Umm-is-Surab, Id-Dêr), the U-shaped cloister with its galleried

porches and its monastic houses ranged peripherally around them is an

invention of the Age of Charlemagne. Its development was dependent,

for one, on the rejection of the semi-eremitic forms of living of the Irish

monks in favor of the highly controlled and ordered forms of communal

living prescribed by St. Benedict. The U-shaped form also answered the

necessity of separating the monks' living quarters from those of the

monastery's serfs and workmen, who entered an economic symbiosis

when the monastery acquired the structure of a vast manorial estate in

the new agricultural society that arose north of the Alps (Horn, op. cit.,

47-48).

On Silchester, see J. G. Joyce, 1881, 344-65, and above, p. 200. On

the basilica of Augst, see Reinle, 1965, 34 and above, p. 200.

III.1.4

CLOISTER YARD

The Cloister Yard is attached to the southern flank of the

Church (fig. 203). It consists of an open inner court surrounded

on all sides by galleried porches, through which the

monks must pass in order to move from one of their three

principal claustral structures to another. The claustral range

connects with the Church, on ground floor level, through a

door in the southern transept and, on the level of the

Dormitory, through a night stair used primarily in connection

with the services held at night or at dawn. The official

"exit and entry" (exitus and introitus) to the Cloister is the

so-called Parlour, a narrow and somewhat elongated room,

located between the Church and the Cellar. Permission to

enter this room for conversation with visiting friends or

relatives, or to pass beyond the barrier of its carefully controlled

passages into the outer monastery grounds or into

the secular world can only be granted by the abbot, and

only for the specific needs, such as labour in the workshops,

garden and fields, or the rare occurrence of a journey to

another monastery conducted in the common interest of

the abbey.

In all other respects the cloister of the monks is hermetically

sealed off from the world around it by the continuous

UMM-IS-SURAB, SOUTHERN SYRIA

193.C

193.B

CONVENT OF SS. SERGIOS AND BACCHOS (489)

[after Butler, 1929, 47, fig. 45]

The only extant Early Christian example of a monastery with claustral

layout similar to that which became standard in the Carolingian

period: a four-cornered open court surrounded by galleried porches and

a continuous enclosure of apartments—the whole attached to one flank

of the church. Both apartments and cloister walks are of two stories,

and beneath the open court lies a coextensive cistern with transverse

arches carrying the pavement of the court. The cloister is entered

through a vestibule in the center of its east range. Another in the middle

of its south range connects with the church. The relatively small apart-

ments suggest that the monks slept in groups of ten or twenty rather

than in a common dormitory, as was the case in Carolingian times.

193.A

three principal claustral ranges.

DIMENSIONS

In his commentary to the Rule of St. Benedict, written in

Civate between 845 and 850, Hildemar of Corbie remarks

that the cloister of a monastery should be "large enough so

that the monks can attend to all of their chores without

finding cause for murmur, yet not so grand as to invite

them to spend their time in gossip" (Nec debet esse ista

parva, ut cum aliquid vult operari monachus, occasionem

invenerit murmurandi propter parvitatem, nec ita debet esse

ampla, ut ibi occasionem possit invenire fabulandi cum

aliquo).[16]

And in a subsequent paragraph he adds the

important piece of information that in his day, "It is

generally held that a cloister should be 100 feet square, and

not less, because that would make it too small; however if

you should wish to make it larger this is permissible"

(Dicunt multi, quia claustra monasterii centum pedes debent

habere in omni parte, minus non, quia parva est; si autem

velis plus, potest fieri).[17]

The cloister yard of St. Gall complies

with this rule (figs. 69 and 203). It measures 100 feet

contains in its center an open space 75 feet square, and all

around it a galleried walk.

THE PUZZLE OF THE SAVIN PLANT

The yard, which was perhaps covered with grass, is

intersected by four paths (quattuor semitae p transuersum

claustri) that emerge from the middle of each cloister walk

and terminate in a square enclosure decorated in the center

with a circle, designated sauina, and four branch-like

symbols extending from the circle outward into the corners

of the square.

Savina or savin are common names for Juniperus sabina,

a low, spreading shrub or small tree of Mediterranean

origin that was introduced in Germany and France in pre-Carolingian

times and from there its horticultural use was

extended to England.[20]

A profusely illustrated Byzantine

copy of the famous Herbal of Dioscurides displays a delicate

drawing of this tree (fig. 204).[21]

The leaves of this plant

to be barred from public parks.[23] Yet in the Middle Ages,

as well as in classical Roman times it was used for a variety

of medical cures. Dioscurides, writing in the first century

A.D., informs us that applied as a poultice the leaves of the

savin tree stop spreading ulcers and soothe boils, mixed

with honey they cause carbuncles to break; drunk with

wine they draw out the blood by urine and draw off the

foetus.[24] More recent sources attest their use as a cure

against the spread of intestinal worms, primarily for cattle,

a purpose to which this herb is applied even today by the

peasants of Southern and Central Germany.[25]

The savin is one of the plants prescribed in the Capitulare

de villis as obligatory for the gardens of Carolingian crown

estates.[26]

It is also mentioned in the Brevium exempla

amongst the plants grown in the royal fisc of Treola.[27]

In

ID-DÊR, MONASTERY, SOUTHERN SYRIA, 5TH CENT.

194.B

194.A

[after Butler, 1929, 88, fig. 91]

"The most dignified, and most symmetrically planned of the monastic

institutions of Syria" (Butler, 1929, 85-85) now lies in ruins, deserted.

It consisted of an aisled basilican church attached to the east side of a

great open atrium, enclosed by apartments of two stories, all opening

upon pillared porticos likewise of two stories. The layout is unique for

its period and place, an adaptation to monastic use of the atria of the

great metropolitan churches of Rome. The same influence produced in

Carolingian times similar and equally atypical solutions (Fulda, fig.

169, and Kornelismünster, fig. 147).

the herbs, not with the trees.

Sörrensen describes the species as a shrub-like plant of

jagged growth, in general not growing higher than 3-10

feet, never forming a straight stem, but always growing

crooked and bent. He wonders why a plant so entirely

lacking in tallness, fullness, and beauty should occupy such

a central position in the life of the monks.[28]

I had occasion to study the savin in the summer of

1968 while on vacation on the Island of Ibiza in Spain,

where it grows profusely, and was fascinated to observe

that on this island it attains a considerably wider range of

shapes and sizes than one would gather from Sörrensen's

description. At the edge of the windswept coastal cliffs, the

plant hugs the ground and retains a prostrate mushroom-shaped

form attaining a diameter of up to 15 feet but

195. INISHMURRY, SLIGO, SOUTHERN IRELAND

MONASTIC CASHEL FOUNDED BY ST. MOLAISE, EARLY 6TH CENT.

[after Leask, I, 1955, 12, fig. 1]

The monastery, surrounded by a 13-foot stone wall, is internally

divided into four separate enclosures. The largest contains two

churches, a large one with ANTAE, Teampull na b Fhear (Men's

Church) and the smaller, more primitive Teach Molaise (St.

Molaise's Chapel). A third, Teampull na Teine (Church of the Fire)

stands in the northwest enclosure; next to it are the schoolhouse, a

dry stone beehive hut, and a smaller hut of the same type. In the

southern enclosure lie remains of a third very large beehive hut.

Reconstruction shows only buildings sufficiently preserved to leave

tangible evidence of their original appearance. The number of

dwellings must have been considerably larger, though evidence for

them has vanished.

205). In more sheltered places 200 to 300 yards inland, it

rises to tree height of 17 feet, with two or three stems of

relatively straight growth emerging from a common trunk,

but usually hidden by the spreading branches completely

covered with short imbricated leaves (fig. 206). This

variety can be of a full and well-shaped form—somewhat

like the juniper trees on the high desert plateau that borders

on the east slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Yet

another variety, often rising to similar height has boldly

contorted trunks fully exposed, to a height of 6 to 8 feet,

and above that level branching out into a crown that

resembles that of an umbrella pine (fig. 207).

I feel as much at a loss as Sörrensen did, in explaining

why the savin should occupy such a central place in the

planting program of the Plan of St. Gall. The fact that it is

an evergreen must certainly have been an important consideration;

its medicinal benefits unquestionably another,

and not least, perhaps, the fact that its leaves were used in

the making of spiced wine. And one also wonders whether

its aromatic substance may have been a component of the

materials used in making incense. In contrast to Sörrensen,

I would not consider its size or shape to have been a deterrent

factor. One of the most precious features of the

cloister yard, the only place where the monks had daily

access to nature, was its exposure to the sun. To have it

planted with trees of clearly limited height had its advantages.

The architect who designed the Plan of St. Gall appears

to have been aware of the botanical characteristics of the

savin. He defines it visually as a prostrate plant with

straight branches spreading out from the center to the four

corners of the planting square, their short set boughs being

set in the manner of herring bones. The whole is of a

design that is quite distinct from the erect curvilinear

symbol used for tall trees in the Monks' Cemetery (fig. 17).

either a single tree or to designate a cluster of trees. The

planting bed, 17½ × 17½ feet square, is large enough to

accommodate a tall tree in the center, with four lower, more

prostrate plants around it spreading out into the corners.

In German Sevenbaum, Sebenbaum, Sadebaum; in Anglo-Saxon

safine; in Old French savine (see Kluge, 1957, 696). See Fischer-Benzon

1894, 80; Sörrensen in Studien, 1962, 197. Willis' interpretation of

savina as "tub, either for water or for plants" (Willis, 1848, 100) is

untenable. The mistake was inherited by Leclercq (Cabrol-Leclercq,

1924, col. 98) and others.

Vienna, National Library, Ms. Med. Gr. 1, fol. 84r. The manuscript,

written and illustrated in 512, is now available in a precious

fascimile edition. See Dioskurides, Complete fascimile edition, I, 1966,

fol. 84r.

Thus according to Fischer-Benzon, loc. cit. and Sörrensen, loc. cit.

yet without further reference. My colleague Lincoln Constance informs

me that all junipers have some medicinal properties, particularly of a

diuretic nature, that, with injudicious use, could be poisonous, but finds

nothing in the botanical literature available to him to indicate that

Juniperus sabina is poisonous enough to warrant its exclusion from

horticultural planting. Junipers would be poisonous only upon ingestion,

not upon contact, and they are far from enticing to human nibblers.

For the Greek text see Pedani Dioscoridis Anazarbei De materia

medica libri quinque, cap. 104, ed. Curtius Spregel. Leipzig, 1829,

104-105. The full passage, as translated by my colleague W. Kendrick

Pritchett reads as follows: "On savin (brathu). Brathu, some call it

barathron, others baryton, still others baron. The Romans call it Herba

sabina. There are two kinds of it. The one is like to the cypress in its

leaves, but more prickly and of more oppressive smell, pungent, fiery.

The tree is stunted and is diffused rather into breadth. Some use the

leaves as a perfume. The other kind is like to the tamarisk in its leaves.

The leaves of both stop spreading ulcers and soothe boils when applied

as a poultice. Likewise, they remove blackness and uncleanness when

applied as with honey, and they cause carbuncles to break. Drunk with

wine they draw out the blood through the urine, and draw off the

foetus. They do the same whether by being applied or by being burnt

for fumigation. They are mixed also with calorific unguents, especially

the must (new wine)." For less comprehensible translations into English

and German made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries see The

Greek Herbal of Dioscurides, ed. Goodyer 1655, 54-56 and Kräuterbuch,

ed. Danzius-Uffenbach, 1610, 47.

Capitulare de villis, chap. 37, ed. Gareis, 1895, 63. For more details

on this source see below, pp. 33ff.

Brevium exempla, chap. 37, ed. Boretius, 1883, 256. For more details

on this source, see below, pp. 36ff.

THE GALLERIED PORCHES

The arches (arcus) of the four covered walks which

surround the cloister garth are shown in vertical projection.

They consist of a central opening 10 feet wide and 7½ feet

high, and a group of four arches, each 5 feet wide and 5 feet

high, on either side of this passage, which unquestionably

rested on a low basement wall. The north walk of the

Cloister which runs along the southern aisle of the Church

(porticus ante eclam) is broader than the other three. From

the inscription we know that this walk performed the

function of the later chapter house, and for that purpose is

provided with two long benches, both on the Church and

on the cloister side, where the monks could face each other

in two single files; Hic pia consilium pertract & turba

deliberations").[30] It was here that a monk could confess his

sins and ask for forgiveness, that the overseers (circatores)

would announce transgressions of any sort committed by

the brothers, that one monk could accuse another, and that

punishment was pronounced and enforced, including such

corporal chastisement as flogging. It was here also where

much of the temporal business of the abbey was transacted,

where charters were sealed, where novices were admitted,

and where the dead and departed were commemorated.

In subsequent centuries these activities were transferred

to a special chapter house. In Carolingian times, it seems,

this step had not yet been undertaken.

The claims advanced by Georg Hager and Joseph

Neuwirth that separate chapter houses existed in the Abbey

of Jumièges as early as the seventh century and at Reichenau

in 780 are untenable. It is based, in the case of Jumièges

on an improper textual exegesis of a good hagiographical

source (Life of St. Philibert, d. 750), and in the case of

Reichenau, on a twelfth-century forgery of a deed alleged

to have been written in 780.[31]

An arrangement very similar to that shown on the Plan

of St. Gall existed in the Abbey of St.-Wandrille (Fontanella).

An account written by a contemporary of Abbot

Ansegis (d. 833) tells us that the latter "was buried outside

the church of St. Peter, and to the north of it, in the

porticus wherein the brethren are accustomed to hold their

meetings" (tumulatus extra basilicam s. Petri ad aquilonalem

plagam, in porticu, in qua fratres conventum celebrare soliti

sunt ac consultis Deo dignis aures accomodare).[32]

This same

porticus, as George Forsyth has pointed out,[33]

is mentioned

earlier in the chronicle as built by Ansegis himself to be a

place "where the brethren should gather together to seek

insight on all subjects, to listen daily to the reading of the

Holy Writ, and to consider any proposed action" (propter

quod in ea consilium de qualibet re perquirentes convenire

fratres soliti sint; ibi namque in pulpito lectio cotidie divina

recitatur, ibi quicquid regularis auctoritas agendum suadet,

deliberatur).[34]

The inscriptions on the three other walks explain the function of

the lower stories of the buildings to which they are attached, and shall be

dealt with in conjunction with the latter.

See Georg Hager, 1901, col. 98 and Joseph Neuwirth, 1884, 52ff.

For a detailed discussion of their views and the sources on which they

are based see Carolyn Marino Malone, "Monastic Planning after the

Plan of St. Gall: Tradition and Change." Master's Thesis, University

of California at Berkeley, 1968, 27-38, and II, 315ff.

Schlosser, 1896, No. 870 and Gesta, ed. Lohier and Laporte, 107.

With regard to the interpretation of this passage, see Schlosser, 1889,

31-32. Forsyth (loc. cit.) in his interesting analysis of the passage has

interpreted the term porticus as "chapter house." A more appropriate

translation, in my opinion, would be "cloister wing." It is in this sense

that it is used in a later portion of the same passage of the Gesta abbatum

Fontanellensium loc. cit.: "Item ante dormitorium, refectorium et domum

illam quam maiorem nominavimus, porticus honestas cum diuersis pogiis

aedificari iussit."

On the Plan of St. Gall the term porticus is never used for the principal

space of a building or for an independent structure, but always for a

subordinate unit, such as the aisles of the Church, the galleried wings

of the various Cloister yards, and the galleried porches of the Abbot's

House.

III.1.5

DORMITORY AND WARMING ROOM

On the Plan of St. Gall the building that contains the

Dormitory of the Monks bounds the cloister to the east and

lies in direct axial prolongation of the transept of the

church (fig. 208). It is a double-storied structure, 40 feet

wide and 85 feet long. The ground floor serves as the warming

room, the upper floor is the dormitory (subtus calefactoria

dom', supra dormitorium). A hexameter inscribed into

the adjacent cloister walk informs us that this building can

be heated:

Porticus ante domun st& haec fornace calentem.

Let this porch stand before the hall which is heated by

a furnace.

The plan of this building comprises elements of both the

lower and the upper story. The seventy-seven beds of the

monks (lecti, similt) as well as the doors that open from

this building to the transept of the church, to the cloister,

and to the monks' privy are obviously related to the

dormitory. The "exit from the warming room" (egressus

de pisale), which leads to the monks' bath house, on the

other hand, and the large "firing chamber" (caminus ad

calefaciendū) as well as the "smoke stack" (euaporatio

fumi) which are attached to the eastern wall of the building,

relate to the calefactory on the ground floor.

Dormitory

HOW THE MONKS ARE TO SLEEP

How the monks are to sleep is set forth in chapters 22 and

55 of the Rules of St. Benedict. According to these, each

monk must have his separate bed, assigned to him in

accordance with the date of his conversion. If possible, all

of the brethren should sleep in one room; but if their

number does not allow this, in groups of ten and twenty,

with seniors to supervise them. The young monks may not

sleep in a group among themselves, but interspersed with

their elders. A light must burn in the dormitory throughout

the night and the monks must sleep "clothed and girt with

girdles or cords," so that they can rise without delay when

the signal calls them to the work of God. They must not

sleep "with their knives at their sides lest they hurt themselves."

"When they rise for the work of God," St. Benedict

advises, "let them gently encourage one another, on account

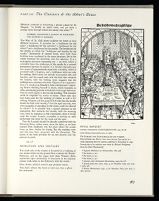

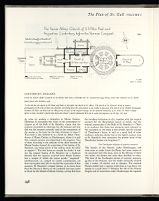

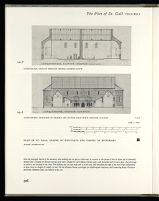

196. ST. RIQUIER (CENTULA)

ANGILBERT'S CHURCH AND CLOISTER (790-799)

[after Effman, 1912, fig. 1]

The original manuscript of Hariulf's Chronicon Centulense,

written before 1088, (ed. Lot, 1894) perished in fire in 1719. It

contained Hariulf's drawing of the Carolingian abbey church and

cloister still in their original condition. His drawing is known through

two copies. The earliest and most authentic (above) was made in

1612 and published in Petau's De Nithardo Caroli magni

nepote, Paris, 1913. Our knowledge of the exterior of the

Carolingian church is derived from it. The interior layout was

reconstructed independently, with virtually the same results, by

Georges Durand (1911) and Wilhelm Effmann (1912) through

analysis of the description of religious services and liturgical

processions in Hariulf's chronicle. The best plan, because it takes into

account irregularities in the Gothic church reflecting conditions of its

Carolingian predecessor, is that of Irmingard Achter, 1956 (figs. 135

and 168).

In waking each other, as Hildemar informs us in more

detail, "the wise and older monk will arouse the brother

who sleeps next to him . . . but no junior monk should ever

arouse another junior, because of the temptation this may

offer for sin (propter occasionem peccati); rather one or two

seniors, after having lit a candle, will walk through the

dormitory to wake the sleepy brothers; yet, in performing

this duty will never touch the brother but only a board of

his bed or something similar."[36]

For bedding they are allowed: a mattress (matta), a

blanket (sagum), a coverlet (lena), and a pillow (capitale).

The possession of any personal property other than that

which is issued to all of the brothers[37]

is severely prohibited,

and in order to guard against infractions of this regulation

the beds are frequently inspected by the abbot.[38]

We must assume that the beds were provided with some

locker or storage space, in which the monks could keep the

duplicate set of clothing which the Rule permitted them

"to allow for a change at night and for the washing of these

garments."[39]

During the hours which are set aside for sleeping,

whether in the day or at night, silence is vigorously enforced

in the dormitory;[40]

but on certain specified periods

of the daily cycle, such as when the monks return from

their chapter readings, they may engage in conversation, in

groups of two or three or more.[41]

Even during the midday

rest in the summer, conversation is permitted, provided

that it does not "injure the peace of those who sit and read

in bed." Should there be any need for sustained talk, the

monks must go outside (i.e., to the cloister walk) and

conduct their business there.[42]

Singuli per singula lecta dormiant; lectisternia pro modo conuersationis

secundum dispensationem abbae suae accipiant. Si potest fieri, omnes in uno

loco dormiant; sin autem multitudo non sinit, deni aut uiceni cum senioribus,

qui super eos solliciti sint, pausent. Candela iugiter in eadem cella ardeat

usque mane. Uestiti dormiant et cincti cingulis aut funibus, ut cultellos suos

ad latus suum non habeant, dum dormiunt, ne forte per somnum uulnerent

dormientem . . . Adulescentiores fratres iuxta se non habeant lectos, sed

permixti cum senioribus. Surgentes uero ad opus Dei inuicem se moderare

cohortentur propter somnulentorum excusationes. Benedicti regula, chap. 22;

ed. Hanslik, 1960, 77-78; ed. McCann, 1952, 70-71; ed. Steidle, 1952,

200-201.

See below under "Vestiary." The synod of 817 added to the

standard equipment which the monks could keep near their beds, a

specified supply of soap and unction; Synodi secundae decr. auth. chap.

38; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 480.

Benedicti regula, chap. 55; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 130; ed. McCann,

1952, 126-27; ed. Steidle, 1952, 269.

Benedicti regula, chap. 55; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 129; ed. McCann,

1952, 124-25; ed. Steidle, 1952, 269.

Consuetudines Corbeienses; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963,

417: "Quando uero dormiendi tempus fuerit siue in die siue in nocte silentium

funditus in ore, ita in incessu, ut nullus iniuriam patiatur, summa cautela

esse debet."

Ibid., 416-17: "Quando loqui licet, quia locutio semper ibi seruanda

est siue duo seu tres seu aetiam plures sicuti fieri solet quando de capitulo

surgunt coniungantur."

Ibid., 417: "Quod si aliquis etiam ad legendum in lectulo suo resederit,

nequaquam alterum sibi ibidem ad colloquium coniungat, sed si

necessitatem loquendi diutius habuerint, exeant foras et ibi loquantur."

LAYOUT OF THE BEDS

The layout of the beds in the Monks' Dormitory is complex

and ingenious. We have already discussed the manner

in which it was designed in our analysis of the scale and

construction methods used in designing the Plan.[43]

The

number 77 is not likely to be an accident.[44]

Yet I have been

able to find only one instance where the number of monks

was confined to this figure.[45]

The Monk's Dormitory, like the two other principal

buildings of the cloister, the Refectory and the Cellar, has

no internal architectural wall partitions whatsoever, and for

that reason must be thought of as a unitary space, open from

end to end. This should not be interpreted to mean, however,

that the beds were in full and open view of everyone

throughout the entire length and width of the building.

They must have been separated from one another by

wooden panels sufficiently high and long to protect the

monks from interfering with one another. The Custom of

Subiaco stipulates "that there be wooden partitions between

bed and bed, so that the brothers may not see each

other when they rest or read in their beds, and overhead

they must be covered [with canopies] because of the dust

and the cold." The same custom also requires "that these

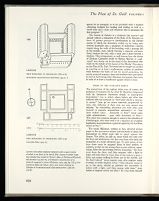

197. ST. RIQUIER (CENTULA). PLAN WITH ABBEY CHURCH & CLOISTER

[after Durand, 1911, 241, fig. 5]

This 19th-century cadastral plan of the city of St. Riquier shows the Gothic abbey church (1) and superimposed in the area to the south the

course of the covered walks that once enclosed its triangular cloister, with the church of St. Benedict (2) in one, and the church of St. Mary (3)

in the other corner. This layout, first suggested by Jean Hubert (1957, 293-309, Pl. 1.C), and again in Hubert, Porcher, and Volbach (1970,

297, fig. 341), on the basis of a documentary study, was confirmed by excavations of Honoré Bernard (Karl der Grosse, III, 1965, 370).

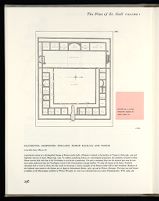

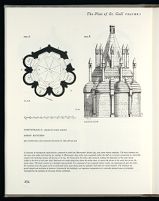

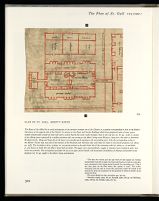

199. LORSCH

FIRST MONASTERY OF CHRODEGANG (760-774)

AXONOMETRIC RECONSTRUCTION [after Behn, 1949, pl. 1]

198. LORSCH

FIRST MONASTERY OF CHRODEGANG (760-774)

PLAN [after Selzer, 1955, 14]

Lorsch is the earliest medieval monastery with a square cloister

attached to one flank of the church. But a layout of similar shape

may already have existed in Pirmin's abbey of Reichenau-Mittelzell,

built between 724 and 750, if Erdmann's reconstruction of its

claustral compound is correct (Erdmann, 1974, 499, fig. TA 4). For

Lorsch see Behn and Selzer, and a more recent summary by

Schaefer in Vorromanische Kirchenbauten, 1966-68,

179-82.

admitting daylight for reading and writing as well as a

small table and a chair and whatever else is necessary for

that purpose."[46]

The Custom of Subiaco is a relatively late source[47]

and

already reflects a relaxation of the Rule of St. Benedict in

favor of greater privacy—a development in the further

course of which the dormitory ended up by being subdivided

internally into a sequence of individual cubicles

ranged along the walls of the building, with a passage left

in the middle, each cubicle forming a separate enclosure

fitted, besides the bed, with a chair and a desk beneath a

window. This arrangement, so well known from the dorter

of Durham Cathedral (built by Bishop Skirlaw in 13981404)[48]

was clearly not in the mind of the churchmen who

ruled on the details of the layout of the Monks' Dormitory

on the Plan of St. Gall. Yet even here we might be justified

in counting on at least a rudimentary system of partition

walls between the beds—if not for moral protection, for

purely practical reasons: since the brothers were permitted

to read in bed during their afternoon rest period, they were

in need of at least a headboard against which to lean.

Sit tamen inter lectum et lectum intersticium tabularum, quod prohibeat

mutuam visionem fratrum in lectis jacencium vel legencium; sintque desuper

cooperti propter pulveres et frigus. Loca eciam sic sint ordinata, ut quilibet

habeat fenestram pro lumine diei ad legendum et scribendum et mensulam

ibidem collacatam atque sedem et hujusmodi que necessaria sunt pro talibus.

(Conseutudines Sublacenses, chap. 3, ed. Albers. Cons. Mon., II, 1905,

125-26.)

The oldest preserved manuscripts of the Consuetudines Sublacenes

(St. Gall Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Lat. 928 and 932) date from around 1436.

See Albers, 1902, 201ff.

FEARS OF THE VIGILANT ABBOT

The eternal fear of the vigilant abbot was, of course, the

pollution of monastic life by what St. Benedict designated

with his distinctive discretion simply as impropriety

(improbitas),[49]

but to which others before and after him

referred with less restraint as "that habit which is contrary

to nature" (usus qui est contra naturam) perpetrated by

men, who oblivious of their own sex turn nature into

iniquity "by committing shameless acts with other men

(masculi in masculos turpitudinem operantes),[50]

or "that

most wicked crime . . . detestable to God" (istud scelus

valde nefandissimum . . . quae valde detestabile est Deo).[51]

The crime was common enough to come to the attention of

Charlemagne, who dealt with it in a vigorous act of public

legislation, incorporated in a general capitulary for his Missi

issued in 802.[52]

The monk Hildemar, writing in 845, devoted several

pages to this precarious subject and discussed in detail the

precautions an abbot must take to guard against this

danger. The abbot, he tells us, must watch not only over

the boys and adolescents, but also over those who enter the

monastery at a more advanced age. To each group of ten

boys there must be assigned three or four seniors, or

masters, so that no one among them is ever without supervision.

After the late evening service, Compline, "the boys

must leave the choir, and their masters, with a light in

hand, will take them to every altar of the oratory to pray a

little, one master walking in front, one in the middle, and

the third behind" (unus magister ante, alter magister vadat

in medio, et tertius magister retro); "then whoever wants to

go to the privy, should go perform the necessities of

nature with a light, and their master with them" (cum

lumine et magister eorum cum illis).[53]

If a boy finds himself

must waken his master, who will light a lamp and take him

to the privy, and with the light burning, bring him back

to bed."[54] Even the dreamlife of the monks and its sexual

connotations are subject to supervision. Depending on the

varying degree of sleep or consciousness, the employment

of the senses of touch and vision, or the extent of deliberate

procrastination, the offense must be atoned for by the

recitation of psalms, five, ten, or fifteen respectively, and

if the indulgence was committed with no restraint, by the

reading of the entire psalter.[55]

Benedicti regula, chap. 2 and 23; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 24, 79; ed.

McCann, 1952, 20-22, 72-73; ed. Steidle, 1952, 82-83, 200-201.

"For a most pernicious rumor has come to our ears that many in

our monasteries have already been detected in fornication and in abomination

and uncleanness. It especially saddens and disturbs us that it can

be said, without a great mistake, that some of the monks are understood

to be sodomites, so that whereas the greatest hope of salvation to All

Christians is believed to arise from the life and chastity of the monks,

damage has been incurred instead. Therefore, we also ask and urge that

henceforth all shall most earnestly strive with all diligence to preserve

themselves from these evils, so that never again such a report shall be

brought to our ears. And let this be known to all, that we in no way dare

to consent to those evils in any other place in our whole kingdom; so

much the less, indeed, in the persons of those whom we desire to be

examples of chastity and moral purity. Certainly, if any such report

shall have come to our ears in the future, we shall inflict such a penalty,

not only on the guilty but also on those who have consented to such

deeds, that no Christian who shall have heard of it will ever dare in the

future to perpetrate such acts." (Here quoted after translations and

Reprints, VI, Laws of Charles the Great, ed. D. C. Monro, n.d., 21.

For the original text see Capitulare Missorum Generale, AD 802, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Legum II, Capit. I, 1883, 94.)

ABSENCE OF STAIRS

The author of the Plan of St. Gall did not consider it a

matter of vital importance to express himself in great detail

about the stairs which connected the Dormitory with the

Church, the cloister, and the privy. He made it absolutely

clear, however, where such connections should be established.

There is no doubt that the door that leads from the

Dormitory to the southern transept arm of the Church

must have opened onto a flight of stairs by which the

monks descended into the Church for their nocturnal services.

A direct ascent to the dormitory a parte ecclesiae in

the Abbey of St. Gall is mentioned in Ekkehart's Casus

sancti Galli.[56]

Flights of night stairs of precisely this type

survive in an excellent state of preservation in the transepts

of the Cistercian abbey churches of Fontenay and Silvacane,

both from about 1150, and the Benedictine abbey

church of Hexham (fig. 101), from about 1200-1225.[57]

The

area in the middle of the Dormitory left unobstructed by

beds might have been meant to serve as landing for an inner

stair connecting Dormitory with Warming Room. This

same stair could also have been used for daytime access

from ground level to Privy, which to judge by numerous

later parallels must have been level with the Dormitory.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 91; ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 322ff; ed. Helbling, 1958, 164ff. Cf. II, 327.

For night stairs in general see Aubert, I, 1957, 304-305. For

Fontenay, see Ségogne-Maillé, 1946, fig. 5; for Silvacane: Pontus, 1966,

38; for Hexham: Cook, 1961, pl. VII and Cook-Smith, 1960, pl. 39.

A night stair survives in the north transept of Tintern Abbey. Others in

varying degrees of preservation are found in many other medieval

churches (Beaulieu Abbey; St. Augustine, Bristol; Hayles Abbey, and

others). The remains of the earliest medieval flight of dormitory night

stairs known to me are those which have been excavated by Otto Doppelfeld

in the northern transept arm of Cologne Cathedral. They are virtually

coeval with the Plan of St. Gall. See Weyres, 1965, 395ff and 417,

fig. 5.

Warming room

METHOD OF HEATING

The heating system of the Monks' Warming Room raises

interesting historical and technological questions. It consists,

as already pointed out, of an external firing chamber

(caminus ad calefaciendū) that transmits its heat to the

building through heat ducts (not shown on the Plan), the

necessary draft for which is generated by an external smoke

stack (euaporatio fumi).

Identical heating units appear in two other places on the

Plan, the "warming room" (pisale) of the Novitiate and

the "warming room" (pisale) of the Infirmary.[58]

Keller's[59]

attempt to interpret these devices as simple fireplaces is

untenable and was convincingly repudiated by Willis.[60]

They are clearly descendants of the Roman hypocaust

system. The existence of such heating systems in the

Middle Ages is well attested both by literary and archeological

sources. A hypocausterium almost contemporary with

those of the Plan of St. Gall was built by Abbot Ewerardus

at the monastery of Freckenhorst.[61]

An excavation conducted

in 1939 at Pfalz Werla, one of the fortified places of

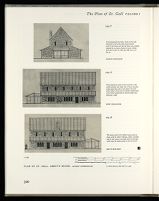

201. LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804). ISOMETRIC RECONSTRUCTION

[after Selzer, 1965, 148]

The abbey grounds, of irregular ovoid shape, were surrounded by a masonry wall. Entering the monastery from the west the visitor stepped into

a large rectangular atrium where he had to pass through what can only be called the Carolingian equivalent of a Roman triumphal arch

accommodating over its passages a small royal hall (a jewel of Carolingian architecture, built 768-774, the earliest wholly preserved building of

post-Roman times on German soil). At the end of this atrium the visitor faced two massive towers flanking a gate that gave access to a second,

considerably smaller atrium lying before the monumental westwork of the church of St. Nazarius, an aisled basilica with low transept and

probably a rectangular choir, built between 767-774, and enlarged eastward in 876 by a crypt for royalty. The component building masses of

this architectural complex rose in dramatic ascent on successively higher levels of the gently rising slope of a natural sand dune; the west gate at

the bottom, the choir of the church at the top, the late Carolingian crypt eight meters below the level of the church on the steeply descending

east slope of the dune.

The walls of the monastery enclosed an area of roughly 25,000 square meters. Forming a veritable VIA SACRA, from gate to altar the route of

passage was nearly 260m. long.

LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804).

200.X

200.

12TH-CENTURY PLAN AND ISOMETRIC VIEW

Fig. 200: after Behn, 1964, 117; Fig. 200.X: after Hubert, Porcher, Volbach, 1970, fig. 377.B]

Toward the middle of the 12th century, the inner Carolingian atrium was converted into a fore church. At the same time, all the claustral

ranges were rebuilt on the foundations of their Carolingian predecessors. (For remains of the latter see Vorromanische Kirchenbauten,

1966, 180).

of such a hypocausterium. There, beneath a hall

constructed between 920 and 930, C. H. Seebach unearthed

a hypocaust in an excellent state of preservation.[62]

Its heating plant (fig. 209) consisted of a subterranean

firing chamber beneath the floor of the hall, which was

reached by an outside passageway. A system of radiant

ducts channeled the heated air from the firing chamber

into a circular flue which lay directly under the pavement

of the hall and was provided, at regular intervals, with

tubular vents through which the warmth ascended into

the hall above. Another large flue ran from this main duct

to the western gable wall where it emptied into a smoke

stack. This flue showed heavy traces of blackening, which

suggests that the hot air outlets into the hall could be

closed by stone lids during the initial firing stages, when

the volume of smoke and obnoxious gas was heaviest,

leaving the chimney as the only outlet.

Seebach believes that the hypocaust system of St. Gall

was identical with that of Werla. However, the two

systems are not alike in every detail. The Werla firing

chamber lay beneath the hall; the firing chambers of St.

Gall are external attachments. They must have been subterranean,

of course, for otherwise the heated air could not

rise into the hall above, but the general principle of construction

was doubtlessly the same, and the occurrence of

this type on the Plan of St. Gall is clear testimony that

202. SILCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND, ROMAN BASILICA AND FORUM

PLAN (after Joyce, 1887, pl. 16)

A provincial variant of a distinguished lineage of Roman market halls, Silchester is related to the basilicas of Trajan in Rome (fig. 239) and

Septimius Severus in Lepcis Magna (fig. 159). To students considering history as a chronological progression, the similarity of layout of these

Roman market halls with that of the Carolingian CLAUSTRUM is perplexing. Yet such a conceptual leap into the classical past may be even

more easily understood than the Carolingian revival of the Constantinian transept basilica. To study the layout of the latter, Frankish

churchmen had to travel to Rome, but they could see surviving or ruinous examples of the Roman market hall in their homeland. Basilicas of

the Silchester type existed in the Roman city of Augst in Switzerland (Reinle, 1965, 34) and in Worms, Germany. The latter was well known

to builders of the Merovingian cathedral of Worms (Fuhrer zu vor-und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, XIII, 1969, 36).

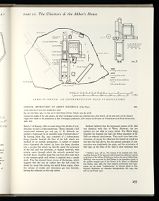

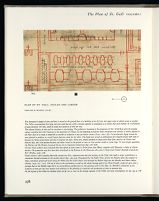

203. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CLOISTER YARD

Although in plan displaying striking similarities with the great galleried courts of the Roman market halls (cf. figs. 202, 239) the four-cornered

medieval cloister shows marked differences in elevation (cf. fig. 192). The Roman basilican courts are vast areas for open-air assembly and

the conduct of business, surrounded by relatively small offices and shops of modest height (fig. 202). The open yard of a medieval cloister, by

contrast is small in relation to the buildings by which it is enclosed. The latter rise high and are surmounted by steep-pitched roofs. Internally,

although composed of two levels, they form open halls extending the entire length of the building. The galleried porches are the only connecting

links between these huge structures, none of which possess interconnecting doors or entrances. The tint block on the opposite page shows the above

cloister (100 feet square) at the scale of the Silchester basilica (1:600).

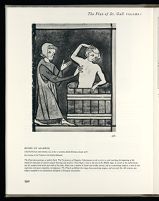

204. DIOSCURIDES. MATERIA MEDICA

Vienna, National Library, CODEX VINDOBONENSIS, fol. 48v

SAVIN PLANT (JUNIPERUS SABINA)

[by courtesy of the National Library of Vienna]

Pedanios Dioscurides of Anazarbos, a physician of Greek descent

who served in the army of Nero, wrote his Materia Medica around

50 A.D. It details the properties of about 600 medicinal plants and

describes animal products of dietetic and medicinal value. The writing

of Dioscurides was well known and widely read in the Middle Ages

and served as a standard text for learning in all medical schools.

The illustration shown above is from a richly (in places even

brilliantly and very realistically) illuminated copy of this treatise

executed by a Byzantine artist in 512, and now available in a

magnificent facsimile edition.

ducts, and a chimney stack for draft and evacuation of

obnoxious gas were, at the time of Louis the Pious, a

standard system used in the construction of monastic

warming rooms. Whether or not the heat produced by this

system could also be conducted into the Dormitory above

remains a moot question.

Nec ab incoepto destitit donec in circuitu oratorii refectorium hiemale et

aestivale, hypocaustorium, cellarium, domum areatum, coquinam, granarium et

dormitorum, et omnia necessaria habitacula aedificavit." (Vita S. Thiadildis

abbatissae Freckenhorsti; see Schlosser, 1896, 86, No. 283). For previous

discussions of the hypocausts of St. Gall see Keller, 1844, 21; Willis,

1848, 91; Stephani II, 1903, 77-83; Oelmann, 1923/24, 216.

Seebach, 1941, 256-73. The remains of the channels and a freestanding

chimney of the hypocaust which heated the calefactory and the

scriptorium of the Abbey of Reichenau, built at the time of Abbot Haito

(806-823), were excavated by Emil Reisser in the immediate vicinity of

the nothern transept arm of the Church of St. Mary's at Mittelzell

(see Reisser, 1960, 38ff). For other medieval calefactories with hypocausts,

see the article "Calefactorium" by Konrad Hecht in Otto

Schmidt, Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, III, 1954, cols.

308-12; and Fusch, 1910.

PURPOSE

The primary function of the calefactory, we learn from

Adalhard, was to give the monks an opportunity to warm

themselves in wintertime in the intervals between the

divine services,[63]

to hang up their clothes for drying,[64]

and

to meet at certain hours for conversation.[65]

This was also

the place, he cannot resist adding, "where the monks on

occasion succumb to drowsiness and neglect their reading

because of the pleasant warmth."[66]

It is possible, as Hafner has pointed out,[67]

that the calefactory

was also used as a general work room, where the

monks did their sewing and mending, or other domestic

chores, when the weather was not mild enough to permit

them to do this in the cloister. The calefactory may also,

during the winter or on days of inclement weather, have

been the place for the weekly washing of the feet of the

monks.[68]

To provide the wood for the hypocaust was the

responsibility of the chamberlain.[69]

Consuetudines Corbeienses; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963,

416: "Si autem hyemps fuerit et calefatiendi necessitas ingruerit, prout ei

qui praeest uisum fuerit siue ante seu post peractum officium aliquod interuallum

fiat, quando se calefacere possint." See Jones, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Et si forte quaedam ad eandem domum spetialiter pertinent

ut est de pannis infusis qui suspenduntur," and translated, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Cum . . . tam colloquendi quam coniugendi tempus licitum

aduenerit," and translated, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Et somnolentis et propter caloris suauitatem minus adtente

legentibus," and translated, III, 123.

See below, p. 307. According to the Usus ordinis Cistercensis the

calefactory is the place "where the brothers warm themselves, grease

their boots, and are bled; where the cantor and the scribes mix ink

and dry their parchment, and where the sacrist fetches light and glowing

cinders." See Migne, Patr. Lat., CLXVI, cols. 1387B, 1447A-C,

1466D, 1497C; and Mettler, 1909, 151.

"Ligna recipiet camerarius conventus et de illis procurabit ignemcopiosum

fratribus" (see under "camerarius" in Du Cange, Glossarium).

RECONSTRUCTION

The reconstruction of the building containing the Calefactory

and the Dormitory poses no major problems (figs.

108 and 111.B). Although no Carolingian dormitory of significance

is preserved, as far as I know, we are fairly well

informed about the materials used in their construction by

contemporary chronicles. The dormitory of Fontanella

(St.-Wandrille), completely reconstructed under Abbot

Ansegis (823-833), is a good example. The Gesta Abbatum

Fontanellensium[70]

tells us that its "walls were built in well-dressed

stone with joints or mortar made of lime and sand"

and that it received its light through "glass windows."

Apart from the walls the entire structure was built with

wood from the heart of oak, and roofed by tiles held in

place with iron nails.[71]

The layout of this dormitory

differed distinctly from the one shown on the Plan of St.

Gall, but like the dormitory of St.-Wandrille, the building

that houses the Dormitory on the Plan of St. Gall was a

masonry structure. This can be inferred from the fact that

the cloister walk with its arched openings attached to it was

unquestionably built in masonry. With its span of 40 feet

from wall to wall, this building required a roof structure

comparable to that of the adjacent church. In the latter the

tie beams of the roof must have crossed the nave in a single

span; in the dormitory—with its live load of seventy-seven

monks on the top floor—the girders that supported the

joists of the dormitory floor are likely to have found

additional support in one or two rows of free-standing

posts.[72]

SAVIN PLANT (JUNIPERUS SABINA)

205.

206.

207.

IBIZA, SPAIN

205. Erect form, sheltered habitat, 300-400 yards inland, Bay of Santa Eulalia.

This globular, symmetrical specimen reaches h. 17 feet, dia. 12-14 feet.

206. Prostrate form, exposed habitat, cliffs near Santa Eulalia. This specimen

has dia. of ca. 15 feet, h. 3-4 feet.

207. Erect specimen, umbrella-shaped crown, beach near Santa Eulalia. H. ca.

15 feet, crown dia. ca. 22 feet.

Gesta SS. Patr. Font. Coen., chap. 13(5), ed. Lohier and Laporte,

1936, 104-105: "Dormitorium fratrum . . . cuius muri de calce fortissimo

ac uiscoso arenaque rufa et fossili lapideque tofoso ac probato constructi

sunt . . . continentur in ipsa domo desuper fenestrae uitreae, cunctaque eius

fabrica, excepta maceria de materie quercuum durabilium condita est,

tegulaeque ipsius uniuersae clauis ferreis desuper affixae." See Schlosser,

1889, 30-31; Schlosser, 1896, 289, and Gesta abbatum Fontanellensium,

chap. 17; ed. Loewenfeld, Script. rer. Germ, XX, 1886, 54.

The same conditions apply to the building which contains the

Monks' Refectory and Vestiary, and the building which contains their

Cellar and Larder.

III.1.6

MONKS' PRIVY

LAYOUT

From the southern gable wall of the dormitory an exit

opens into an L-shaped passageway that leads into the

Monks' Privy. This building is 30 feet wide and 40 feet

long. Along its southern wall it is furnished with a bench

containing nine toilet seats (sedilia) that are slightly larger

than the seats in the other privies, and, unlike them, not

set directly against the wall but parallel to it at a small

distance. A square support in the north-eastern corner of

the room serves as a stand for a light (lucerna) which,

Hildemar postulates in his commentary to the Rule of St.

Benedict,[73]

was a necessity. Short strokes intersecting the

walls at suitable distances designate that the privy should

be furnished with window slits for daylight and ventilation.[74]

Not easy to identify in the absence of any explanatory

titles are three oblong areas in front of the three

remaining walls. Keller interpreted them as tables.[75]

Later

208. PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' DORMITORY AND WARMING ROOM, WITH PRIVY, BATHHOUSE,

AND LAUNDRY

The Dormitory forms the second story of a building 40 feet wide and 85 feet long (see fig. 192). It is furnished with seventy-seven beds that

one must assume were separated by wooden partitions as well as equipped with head and foot boards, and a modicum of locker space for storing

extra clothing. It is not clear whether the Dormitory could be heated, but its location above the Warming Room suggests the possibility that on

cold days heat from the lower chambers might rise into the upper through ducts in the walls or adjustable openings in the floor.

St. Benedict ruled (see above, p. 249) that the brothers "if possible should sleep in one room." This directive is probably the primary historical

impetus for construction of such large sleeping halls. The earliest structure of this type appears to be the dormitory of the Abbey of Jumièges,

ca. 650. (See the reconstruction of the layout of this monastery by Horn, 1973, 35, fig. 35. For procedure followed by the maker of the Plan

in developing the layout of beds within a grid of 2½-foot squares, see above, p. 89. The term DORMITORIUM is not classical and does not appear

in general use before the 8th century; see III, Glossary, s.v.)

ignored them entirely. That they were meant to be tables

seems to me precluded by their dimensions alone (5 × 10

feet and 5 × 17½ feet), not to mention the fact that tables

are not a traditional part of the furnishings of a privy. From

a purely functional point of view one would expect to find,

besides the toilet seats, one or two areas serving as urinals,

a stand with pitchers filled with water or some other means

of providing water for washing the hands, and perhaps a

bin for the storage of straw.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 331: Intelligitur autem,

ut non solum ardeat candela in dormitorio, verum etiam in exitu, quia ubi

et ubi non possunt seniores adolescentiores custodire, nisi fuerit, sicut dixi,

candela ad exitum.

The only other instance where windows are indicated on the Plan

of St. Gall is the Scriptorium, in both cases for compelling functional

reasons, see above, p. 147.

A STRANGE VISIT AT NIGHT: ITS SANITARY,

MORAL, AND ARCHITECTURAL IMPLICATIONS

That straw was used for sanitary purposes in the Middle

Ages may be inferred from a story in Ekkehart's History of

the Monastery of St. Gall, which is of interest in more than

this particular respect. It tells us how the monks of St. Gall

foiled an attempt of Ruodman, the reform abbot of the

neighboring monastery of Reichenau (972-986)[76]

to convict

them of laxity in monastic discipline. Having failed in

previous and more conventional attempts to prove corruption

in the monastery of St. Gall, he took an extraordinary

course of action, which the chronicler describes with painstaking

accuracy: the abbot mounted his horse, rode to St.

Gall, and entered the monks' cloister, unrecognized, in the

depth of night, searching like a thief for evidence that might

support his accusations (equite ascenso sanctum Gallum

noctu invadens claustrum clandestinus introiit, ut siquid reatui

proximum invenire posset furtive perspiceret). Frustrated by

finding no incriminating evidence, he decided upon the

even more unusual expedient of installing himself as a

quiet observer on one of the seats in the monks' privy.

Since this occurred in the monastery in which he himself

had been raised, he was familiar with the layout of the

buildings, and the writer describes with great precision the

steps which the abbot had to take in order to reach his

goal: from the cloister yard where his inquisition started

he went into the church, climbed up to the dormitory, and

from there gained access to the privy (e parte aecclesiae

dormitorium ascendit secessumque fratrum pedetemptivus ascendit

et occulte resedit). As he passed through the dormitory

his presence was discovered by an alert monk from St.

Gall, who instantly woke his fellow brothers, took them in

procession to the privy and placed a shining lantern

(lucerna) in front of the abbot, together with a handful of

straw (stramina)—a derisive gesture, obviously, through

which he invited the distinguished visitor to terminate his

ritual so that he could be properly received by his angry

hosts.[77]

This story helps to clarify a number of points about the 209.A 209.D 209.B 209.C HYPOCAUST OF A FORTIFIED HALL OF HENRY I OF SAXONY A. Plan of firing chamber with anteroom and stairs. Heat travels via

Plan. First of all the fact that the relative location of

PFALZ WERLA, GERMANY