The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. | I.13.5 |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I.13.5

WATERWAYS

The availability of a good water supply was a prime condition

for the proper functioning of a monastic settlement.

This was expressed in unmistakable terms by St. Benedict[270]

and can be inferred from countless later accounts of the

selection of suitable sites for new monastic settlements.

Most monasteries were built in the immediate vicinity of

a stream. When, toward the middle of the sixth century,

Cassiodorus the Senator founded the monastery of

Vivarium near his ancestral home of Scyllacium, in

Calabria, Italy, he established it on the river Pellena,

deflected its flow so that it brought drink to the brothers,

serviced the monastery's garden and mills, and filled the

ponds (vivaria) for the stocking and breeding of fish.[271]

In

like manner, during the reign of King Pepin (751-768),

when Count Wilbertus and Countess Ada searched for an

appropriate site for the new monastery of Lièssies, they

gave primary consideration to the availability of "water for

the running of the mill, the serving of the bakery, kitchen,

hermits were dependent on a good supply of water. St. Gall,

in 612, established himself with full deliberation at the side

of a pool which nature had carved beneath a waterfall of

the river Steinach, in Switzerland, and which he had found

to abound in fish. And a century later when this cell of the

Irish missionary was converted into a cenobitic monastery

by Abbot Otmar (719-759) it was—again deliberately—

erected at the side of this stream.[273] Elaborate waterworks

are known to have been installed by Sturmi (744-799) in

the monastery of Fulda to provide the brothers with drinking

water and to create the required slope for the sluices

which carried the water to the mills.[274]

In general the water required for the sustenance of the

community and the operation of its water-driven works was

diverted from this stream at the upper side of the monastery,

conveyed to the monastic workshops through a carefully

constructed system of flues, and then directed back to

the bed of the stream at a lower level, carrying with it all

of the monastery's waste. In many English abbeys of the

twelfth and thirteenth centuries, where the buildings themselves

have disappeared, the course of the waterways is now

completely exposed, and can be studied under ideal conditions.[275]

When a stream of running water was not available

nearby, the supply had to be brought in from a distant

source by means of an aqueduct.[276]

Such a system of aqueducts existed at the Canterbury

monastery and is depicted on two large sheets of parchment,

now inserted (with somewhat trimmed margins) into the

famous Canterbury Psalter of the Library of Trinity

College, Cambridge.[277]

Drawn around 1165, probably by

Wibert (d. 1167) who engineered the system, these drawings

(one of which is shown in fig. 52.A) trace the course of

the water from its source in the surrounding countryside

through five settling tanks—located in cornfields, vineyards,

and orchards—to a circular conduit house; thence,

through a passage in the city walls into the precinct of the

monastery itself. There is branches out into several separate

subterranean systems serving the monastic houses and

workshops, and finally it empties into the large sewers from

which the waste is carried into the town ditch.[278]

A literary parallel to this depiction of a medieval monastic

water system is to be found in Book II of the Vita prima

sancti Bernardi, written in 1153 by Arnold of Benneval,

who refers to the reconstruction of the monastery of Clairvaux

after St. Bernard's return from Rome in 1133 and the

construction of its waterworks as follows:

With funds abounding, workmen were gathered from outside, and

together with them the monks applied themselves to the impending

project with utmost zeal. Some cut the timbers, others squared off

the stones or constructed the walls, still others divided the river

Aube through a system of branching channels and lifted the bubbling

waters into the mills. Even the fullers, the bakers, the tanners, the

blacksmiths, and all the other craftsmen set themselves to the task

of fitting out the contrivances suited to their work, so that the

foaming river, diverted into every installation through subterranean

channels, may gush forth on its own account and rush to wherever

this is desired, until at length all the services peculiar to these offices

being rendered and the houses cleansed, the once diverted waters

may return to their original bed and restore the river to its proper

volume.[279]

The Plan of St. Gall nowhere suggests the existence of

any waterways. But it would be incorrect to infer from this

that the availability of water and its distribution throughout

the various monastic shops and houses was not a factor of

first importance in establishing their sites. The majority of

the privies are so placed that wastes can be sluiced through

straight channels, and the water-driven mills and mortars

are located at the monastery's edge, where water of an

adjacent stream was apt to be within easy reach. All other

shops and houses are placed in such a manner as to tie them

without difficulty into a logical and simple water system.

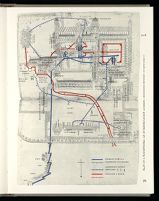

Figure 53 shows how easily a well-planned system of

waterways could be superimposed upon the Plan of St.

Gall.

52.A PLAN OF A WATERWORKS:

CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity Library, Cambridge]

This plan of Christchurch waterworks, together with a supplementary and unfinished

plan of the extra-mural parts of the same waterworks, is inserted as a foreign leaf in

the famous Canterbury Psalter (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, ms. 110, fols. 284b

and 285). The plan dates around 1165 and was probably drawn by Wibert (d. 1167).

It is reproduced here slightly reduced from its original size of 11⅝″ × 16⅝.

For a detailed description and a brilliant analysis of the principles of delineation used in

making this extraordinary drawing, see Willis, 1868, 158ff and 176ff. Additional

literature is cited in James, 1935, 53.

52.B PLAN OF A WATERWORKS: AN INTERPRETATION

CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY

[analysis by Willis, 1868, modified by Wysuph, Horn, Born, 1975]

52.C DESCENT BY GRAVITY FROM SUPPLY SOURCE

AT A HIGHER LEVEL TO TERMINAL

DEBOUCHEMENT

The delineation of Christchurch Monastery tells more as pictorial representation, and

of architectural appearance, than it reveals of functional building planning: waterways

shown are schematic. The document shows a water source on high ground, east of the

Monastery, flowing through five (settling?) tanks in cornfields, vineyards, and orchards,

through the monastery wall to Laver I (east cloister), thence to Laver II (Great

Cloister), thence returning on the east to Laver III. This waterway, with Lavers I,

II, III, may be taken as the primary supply system (solid blue line in Plan and

Diagram). Three secondary branches (segmented blue line) are designated on Plan

and Diagram as 1, 2, 3.

Branch 1 leaves the main line between Lavers I and II, flows southward to a

cemetery fountain, then on to debouche in the Piscina. Branch 2 flows northward

from Laver II to a point south of the Brewery where it turns abruptly eastward to

serve the monk's bathhouse, then flows southward to a tank or catchbasin (M) on the

drainage line (solid red line). Branch 3, departing where Branch 2 flows eastward,

serves the Brewery. A short eastward leg serves the Bakery, a short westward leg, the

Abbot's House. From Laver III, at the end of a short extension eastward, the

primary line terminates, draining into the Piscina (blue dotted line).

In addition to the potable supply system a scheme of drainage (red), more or less

polluted, is discernible. Originating in the Great Cloister, it descends southward and

terminates beyond the walls on the north.

The interpretation (figs. 52.B, 52.C) assumes that the drainage line (red), descending in

a short arc from Vestiarium to abut the roof line on the infirmary complex, continues

directly northward through or under the structure to join the drainage system (from

Piscina and tank M) at or near the Infirmary toilets; thus, non-potable water never

comes in contact with the Piscina.

Benedicti regula, chap. 66; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 140-41; ed. McCann,

1952, 152-53; ed. Steidle, 1952, 320-21.

Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones, I, ch. xxix, ed. Mynors, 1937,

73-75, and translation by Leslie Webber Jones, 1946, 131.

Vitae Galli auctore Walahfrido, Book I, ch. 11 and Book II, ch. 10;

see Vita Galli confessoris triplex, ed. Krusch, 1902, 292 and 319; and

Sankt Otmar, ed. Duft, 1959, 24-25.

Catalogus abb. Fuldensium, see Schlosser, 1896, 121, No. 386. For

more information on monastic water power see the chapter on "Facilities

for Milling, Crushing and Drying of Grain," II, 225ff.

Around 835 Abbot Habertus of Lobbes tried to cut an aqueduct

through steep mountain slopes to put it into the service of his mills but

failed and was forced to abandon his project. Folcuini gesta abbatis, chap.

12; see Schlosser, 1896, 67, No. 237.

The Canterbury Psalter, Trinity College Library, Ms. 110, fols. 284b

and 285; see M. R. James, 1935, last two plates.

The Vita prima sancti Bernardi is in Migne, Patr. Lat. CLXXXV:1,

1879, cols. 225-380 (excerpts in Mortet-Deschamps, II, 1929, 23-27).

It consists of five books of composite authorship, written between ca.

1145 and 1155, by men who all had been friends of St. Bernard and

were eyewitnesses to the events described in their accounts. For further

details, see Williams, 1927, 7ff.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||