The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. | I. 12 |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I. 12

METHOD OF RENDERING

I.12.1

USE OF DIFFERENT COLORS FOR

DRAWING AND EXPLANATORY TITLES

All linear work on the Plan is rendered in a clear vermilion

ink which has retained its original intensity. The lines are

traced without the aid of instruments, in firm and fluent

strokes suggesting that the draftsman had experience with

this type of drawing. The textual annotations are written in

a deep-brown ink, bordering on black. In the crossing,

transept, and forechoir of the Church, brown ink is also

used to thicken the architectural line (fig. 99), obviously

with the intent of clarifying the basic spatial divisions of

the Church, which are somewhat blurred in this area by the

heavy concentration of stairs, altars, benches, and choir

screens.[241]

It is impossible to say whether this was done at

the time the Plan was copied, or at a later stage, preparatory

to its use in actual construction.

The Plan of St. Gall is not the only Carolingian manuscript

where a vermilion red is used for the delineation of

buildings. The Zentralbibliothek in Zurich has among its

holdings an early ninth-century copy of Adamnan's book

De locis sanctis,[242]

written in the scriptorium of the monastery

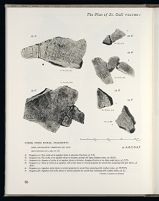

41. PLAN OF THE HOLY SEPULCHER, CHURCH OF JERUSALEM

ZURICH, Zentralbibliothek. Codex Rhenaugensis LXXIII, fol. 5r[243]

[courtesy of the Zentralbibliothek, Zurich]

This plan, as well as the plans shown in the three subsequent figures, were drawn by Walahfrid (d. 849), who copied them from drawings

displayed in Adamnan's De locis sanctis.

Adamnan, abbot of the monastery of Iona from 679-708, in turn derived his knowledge about the layout of these buildings from the

verbal account of the Frankish bishop Arculf who visited the Holy Land around 680, and from drawings engraved into wax tablets by

Arculf for Adamnan's benefit.

42. THE CHURCH OF MOUNT SION

ZURICH, Zentralbibliothek

Codex Rhenaugensis LXXIII, fol. 9v

[courtesy of the Zentralbibliothek, Zurich]

plans of a group of Early Christian pilgrimage churches of

the Holy Land drawn, it seems, by the hand of Walahfrid

Strabo,[244] viz., on fol. 5r, the Holy Sepulcher Church of

Jerusalem (fig. 41); on fol. 9v, the Church of Mount Sion

(fig. 42); on fol. 12r, the Ascension Church on Mount

Olive (fig. 43); and on fol. 18v, the cruciform church of

Samaria (fig. 44). As on the Plan of St. Gall, so here, the

architectural plans are drawn in red, while the explanatory

titles are written in black. This suggests that red might

have been the preferred color for architectural drawings in

the early Middle Ages.

See below, p. 137. Not available to me when these lines were written

was an article by Gerhard Noth, published in 1969, where it is suggested

that this thickening of certain lines in transept and presbytery occurred

"just before and in connection with the reconstruction of the church of

St. Gall by Abbot Gozbert." This is possible, even probable. Yet one

cannot exclude the alternative that this might have been done already in

the scriptorium of the abbey of Reichenau (after the Plan was finished,

but before it was transmitted to Abbot Gozbert) as a last clarifying

measure, undertaken by the corrector, perhaps upon the suggestion of

Bishop Haito, in response to the desire to identify more clearly the outlines

of the basic building masses of nave and transept (cf. below, p. 137).

I am utterly unconvinced of Noth's conjecture that the thickened lines

were meant to convey the idea that the transept was internally divided

into three virtually separate compartments by strongly protruding wall

spurs. It is much more reasonable to assume that these lines were added

to emphasize the fact that the nave intersected the transept in its full

height and width, and to preclude a confusion between the boundaries of

these two primary spaces with lines that designate such secondary

appurtenances as choir screens, steps and benches of which there is a

heavy concentration in these parts of the church. On Noth's reluctance

to admit the concept of a disengaged crossing for the Church of the Plan

of St. Gall, see the arguments offered below, pp. 92ff.

For Cod. Rhenaug. LXXIII, see Katalog der Handschriften der

Zentralbibliothek Zürich, III, 1936, 190-91. Adamnan, abbot of Iona

from 679 to 704, based his book De locis sanctis (presented to King

Aldfrid the Wise of Northumbria in 701) on the travel account of Arculf,

a Frankish bishop and pilgrim, who visited the Holy Land about 680 and

on his return to Gaul was driven by adverse winds to Britain where he

took refuge in the monastery of Iona. See S. Adamnani . . . de locis

sanctis, ed. Migne, Patr. Lat., LXXXVIII, 1844, cols. 779-815, and the

annotated English translation published by Macpherson in 1899. For

excerpts see Schlosser, 1896, 50-59; and Preisendanz, 1927, 20ff. For

better and more recent editions and translations (brought to my attention

by Charles W. Jones) see James F. Kenny, Sources, I, 1929, 285-88.

I.12.2

COMBINATION OF VERTICAL AND

HORIZONTAL PROJECTION

All buildings and installations shown on the Plan are

rendered in vertical line projection. In certain instances,

however, to this projection is added a straight-on view,

showing the elevation of a wall as though it were lying flat

on the ground. Examples of this are: the arcaded walls of

the cloister walks (Monks' Cloister [fig. 191], Novitiate and

Infirmary [fig. 236]), the arcuated porches of the Abbot's

House (fig. 251), and details such as the crosses on the

altars of the Church (fig. 251), or the monumental cross in

the graveyard (fig. 430). In tracing these elements the

architect made use of the mason's age-old habit of sketching

architectural elevations on the ground when explaining the

design of a building to an apprentice or a client. The method

was even more familiar to carpenters, who not only laid out

but actually cut, assembled, and jointed many of their roof-supporting

trusses on the ground before raising them into

the vertical plane with pulley and ropes.

The designer of the scheme of the Plan employed this

device with discretion—only in places that offered sufficient

space to use it without obstructing other architectural

features or blurring the general clarity of the Plan. In this

manner he succeeded in conveying to the builder, in unmistakable

language, not only the design but also the exact

proportions of the great galleried porches that surrounded

the cloister yards and served as connecting links between

the claustral buildings.

The combination of vertical and horizontal projection in

one and the same architectural drawing or plan probably is

a principle as old as architecture itself and common to all

periods. It was firmly established in Egyptian art and was

there refined to a point where it depicted not only the

planimetrical layout of the buildings with which it was

concerned, but also the human events that took place in

these settings. This led to compositions of great complexity,

in which features drawn in elevation (favored because of

their ability to tell a story more fully and more conspicuously)

tended to overcrowd and blur the plan.[245]

The house

shown in figure 45.A-B is a simple and easily readable

example of this tradition. Others are not so susceptible to

easy interpretation.[246]

It is not so widely known that an admixture of vertical

and horizontal projection is also found in Roman architectural

drawings, although there it is not used with comparable

43. CHURCH OF

THE ASCENSION ON MOUNT OLIVE

ZURICH. Zentralbibliothek. Codex Rhenaugensis LXXIII, fol. 9r

[courtesy of the Zentralbibliothek, Zurich]

44. CRUCIFORM CHURCH OF SAMARIA (ISRAEL)

ZURICH. Zentralbibliothek. Codex Rhenaugensis LXXIII, fol. 18v

[courtesy of the Zentralbibliothek, Zurich]

Forma urbis, the now-fragmentary plan of Rome that was

incised in marble during the reign of Emperor Septimius

Severus, between A.D. 205 and 208.[247] Generally rendered in

vertical projection (typical examples are shown in fig. 46),

this plan shows arcuated elements incised in elevation in at

least three different places, each time in connection with the

representation of an aqueduct (fig. 47.A-C).[248] As on the Plan

of St. Gall this delineation of arch forms occurs only in

relatively uncluttered areas of the Forma urbis; in more

crowded sections a more compact symbol of piers, or bars

connected by two curved lines, is used (fig. 47.D-F) for

aqueducts as well as other types of arches.

The aqueducts rendered in elevation occur on fragments 215, 223,

and 612. Carettoni et al., op. cit., II, plates 41, 42, 56, respectively;

discussion, ibid., I, 206.

I.12.3

LACK OF DEFINITION OF WALL

THICKNESS

The walls of the buildings of the Plan of St. Gall are 45.A 45.B FROM A TOMB, VICINITY OF Schech Abd el Gurna [after Borchard, 1907-1908, 59, figs. 1 and 2] A. Tracing of relief. The dotted lines give the location of B. The plan of the house as it would be rendered in a modern The stage of the scene is a rectangular house, the plan of which is

rendered as simple lines. This fact has given rise to two

widely held assertions of questionable validity. One of

these, voiced as early as 1848[249]

and frequently reiterated, is

that the designing architect failed to give any consideration

to wall thickness. The other, more recently advanced, is

that any preoccupation with wall thickness would have been

intrinsically incompatible with the ideal character of the

Plan.[250]

As far as the first of these two contentions is concerned,

attention must be drawn to the fact (generally overlooked

in previous discussions of this point) that there are

two significant exceptions: the bases of the columns in the

nave of the church and the foundations of the arcade piers

in the western paradise are rendered as squares, in their full

planimetrical extension. Second, although the draftsman

drew his walls in simple lines, there is clear indication that

he was fully aware of the complications that might arise in

the actual erection of buildings drawn in linear projection

in such areas of the site where the masonry in two adjacent

structures would congest the available building space, unless

special provisions were made to forestall that eventuality.

The fact that the aisles of the Church are 22½ feet

wide and not 20 feet, as their titles prescribe, finds its

explanation, as will be shown later on, in the draftsman's

awareness of this danger.[251]

Yet even here he does not go so

far as to draw the walls with two parallel lines, but guards

himself against cluttering his plan with unnecessary details

by simply moving his wall lines farther outward and thus

introducing a safety margin of 2½ feet on either side of the

Church. His decision to render the walls of the buildings by

single rather than double lines has little to do with the ideal

or paradigmatic nature of his subject, but is clearly conditioned

by the small scale of the Plan. Even today, as Konrad

Hecht has pointed out correctly, an architect faced with the

design of a project of similar complexity, drawn at a comparable

scale, would invariably choose the same method.[252]

It was for this very reason that the architects who designed

the monumental marble plan of the city of Rome chose

EGYPTIAN WALL RELIEF

explanatory titles.

architectural drawing.

traced in vertical-line projection, while the roof-supporting columns

are rendered in section by a symbol formed by two concentric circles.

The doors are shown in elevation, some horizontally, others

vertically, whatever the available space suggested as the more

advantageous solution. The figures are shown in elevation in the

customary Egyptian manner.

46.A.B.C. FORMA URBIS ROMAE

ROME, ANTIQUARIUM COMMUNALE DEL CELIO

[after Carettoni, Colini, Cozza, and Gatti, Rome, 1960]

These fragments are of a plan of the city of Rome, etched in marble during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus, between A.D. 205 and 208.

This plan, incised on numerous marble slabs, was installed near the Forum of Peace, on the wall of a building which before the fire of 192

served as municipal archives. A probable outgrowth of the emperor's fiscal reform, the plan may have served as a monumental compilation and

permanent record of numerous archival and boundary maps. Mounted on a base 4 meters high, the plan itself covered a surface about 42½ feet

(13m) by about 59 feet (18m), an impressive area of ca. 2,500 square feet (234 sq. m). It was drawn at a scale of 1:240, occasionally varying

to 1:245.

The walls of the overwhelming majority of buildings are drawn in single-line projection. A typical example of this method is shown in A, a

marble fragment showing the plan of the Horrea Lolliana and adjacent structures (fragment 25; Carettoni, pl. XXV). Exceptions to the rule are

found in the rendering of the plans of temples, where the cellar walls are indicated by parallel lines, as is shown in fragments 31bb and 37a,

delineating the temples of Argentina and Juno (IBID., pls. XXIX and XXXII, respectively).

walls.[253] When the Romans were faced with the task of

drawing the plan of an individual building, at a larger scale,

they defined the walls in thickness by two parallel lines, as

was done on the marble slab of Claudia Octavia, now in the

Museum of Perugia (fig. 48), and on a number of other

Roman fragments displaying house plans.[254]

This mode of rendering is of great antiquity and we can

safely assume that it was used at all times in all civilizations.

It existed in Egypt at the side of the more pictorial representations

of the type exemplified by figure 45.A, as is clearly

displayed by the detail of a house plan of the New Kingdom

shown in figure 49. Indeed the most accomplished plans

of this kind, as Ludwig Borchard has pointed out, were

probably those which Egyptian architects chiseled in full

size into the pavement of sacred sites, to be used as guidelines

for the masons who built the walls of the temples that

rose in these places.[255]

The designers of the Forma urbis

were not entirely consistent in their use of the single line,

but interspersed it with a small number of buildings where

walls are defined by parallel lines. This was done, it seems

without exception, in the rendering of temples (here

exemplified in figures 46.B-C)[256]

and it looks very much as

though this departure from the regular method may have

been motivated by the desire to throw into visual prominence

buildings of a strictly religious nature. The designer

of the Plan of St. Gall could have introduced a similar variation—the

church plans in the Cod. Rhenaug. LXXIII

(figs. 41-44) show clearly enough that the definition of

wall thickness by means of parallel lines is fully within the

range of working patterns of a Carolingian architect. If he

chose to stay away from this type of rendering, he did so

predominantly for stylistic reasons, viz., the desire for

homogeneity of design and, above all, an unwillingness to

clutter up his plan with parallel lines that could be confused

with benches, or run parallel to benches, as they would have

done practically everywhere along the walls of the Church.

Willis, 1848, 89: "The walls of the buildings, the furniture, and

every detail, are alike made out by thin single red lines, without regard

to the proportional thickness of the different objects."

Poeschel, 1957, 28; 1961, 14; and in Studien, 1962, 28: "Die Welt in

der es Mauerstärken gibt ist eine andere, realere, als jene des Kloster-planes,

der ein Idealschema darstellt."

The Plan of St. Gall, as will be shown later on, was drawn at a scale

of 1:192 (see below, pp. 83ff). The Forma urbis Romae was drawn at a scale

of 1:240, varying occasionally to 1:245. See Carettoni et al., op. cit., I,

1955, 210.

For the marble slab of Claudia Octavia see Hülsen, 1890; and

Carettoni et al., op. cit., 210; and Arens, 1938, 19.

I.12.4

DIFFERENTIATION OF LEVELS IN

DOUBLE-STORIED STRUCTURES

Whether a building on the Plan is a single- or a double-storied

structure cannot be inferred from its linear layout.

Structures of several stories are designated as such by their

explanatory titles. One must infer from this that other

buildings, which are without such explanations, are one-storied.

The multi-level buildings are: the Dormitory (fig.

208), the Refectory (fig. 211), and the Cellar (fig. 225), the

Abbot's House (fig. 251), the choir and crypt of the Church,

the Sacristy and the Vestry, the Scriptorium and the

Library (fig. 99). In projecting the design of these buildings

onto his parchment, the draftsman is not consistent, but

switches from the rendering of the ground floor to that of

the second story, whichever is of greater interest to him.

Thus, he depicts the layout of the Refectory with its tables

and benches in full detail and merely indicates with the

inscription supra uestiarium that the Refectory is surmounted

by an upper level serving as storage for the

monks' clothing (fig. 211). In the case of the Dormitory

(fig. 208) he follows the opposite procedure. He depicts the

layout of the upper story with the beds of the monks and

explains with the inscription subtus calefactoria dom' that the

building has a lower level, which is occupied by the warming

room of the monks. Conversely, in the case of the Cellar

(fig. 225), he dwells with loving care on the two impressive

rows of wine and beer barrels set up on the ground floor,

and suggests by the legend supra lardariū. &' necessariorū

repositio that the Cellar is surmounted by the Larder. In

only one case, namely that of the choir and the crypt, are

elements of two levels combined on the same surface. The

area is of crucial importance from a liturgical point of view,

and the draftsman uses this device to make absolutely sure

that it is clearly understood in what manner the pilgrims

are given access to the tomb of St. Gall.

The designers of the Forma urbis Romae also seem to

have felt free to switch from the predominantly ground-floor

layout method to an ideographic rendering of the

superstructure, when this was a more interesting and

significant aspect. Buildings such as the Colosseum (fig.

50.A) or the Theater of Marcellus (fig. 51.A) are rendered in

bird's-eye view, or in a combination of bird's-eye view and

planimetrical projection. Thus in the Colosseum a sequence

of elliptical lines defines the four major sections of the

theater, corresponding to the podium and the three maenia

for the spectators, suggesting rows, yet not specifically

representing them in their actual number.[257]

In the representation

of the Theater of Marcellus (fig. 51), in addition

to the semicircular tiers of seats and the passage ways

(praecinctiones) by which these are separated, there is a

complex system of fan-shaped passages that intersect the

seats radially. Some of these represent the ascending stairs

in the superstructure that connect the three tiers (cavea) of

seats (and would have been visible to anyone seated in the

theater); others show the hidden ramps (cryptae) in the substructure

(not visible from above) that give access to the

upper deck through openings (called vomitoria, because

they "spit out" the masses of spectators into the galleries).

This is an ideogrammatic contraction on one and the same

plane of elements belonging to different levels and not

visible simultaneously from the same point of inspection.

A comparison of the portrayal of these two buildings on the

47.A,B,C,D,E,F FORMA URBIS ROMAE, FRAGMENTS

ROME, ANTIQUARIUM COMMUNALE DEL CELIO

[after Carettoni et al., 1960, vol. II]

A. Fragment 517. Four arches of an aqueduct shown in elevation (Carettoni, pl. LII).

B. Fragment 223. Five arches of an aqueduct shown in elevation, perhaps the Aqua Alsietina (IBID., pl. XLII).

C. Fragment 612. Sequence of arches of an aqueduct shown in elevation, changing direction at an obtuse angle (IBID., pl. LVI).

D. Fragment 215. Series of arches of an aqueduct, with arches shown in vertical projection by curved lines connecting with piers (IBID., pl. XLI).

E. Fragment 413. Aqueduct arches shown in vertical projection by curved lines connecting with crossbars (IBID., pl. XLVIII).

F. Fragment 480. Aqueduct with arches shown in vertical projection by curved lines connecting with crossbars (IBID., pl. L).

* position of fragment not identified

subjects (figs. 50.B and 51.B) shows in the rendering of these

details how little they conform to a consistent scale or to

dimensional accuracy—and how difficult it is (especially

in the case of the Marcellus Theater) to determine what

belongs to the upper deck and what to the supporting

structure. To render the relationship of all these elements

in accurate planimetrical projection would have necessitated

making as many separate plans as there are different stories

in each building (or a combination thereof as is done in

figs. 50.B and 51.B), which was clearly beyond the scope and

function of the Forma urbis. In his rendering of the Colosseum

the designing architect confined himself to portraying

in a crudely abbreviated form what a spectator

would have seen of the elliptical seating arrangement of this

amphitheater, had he hovered vertically above it. In his

portrayal of the Theater of Marcellus, by contrast, he made

an attempt to combine distinctive features of the substructure

(not visible from above) with distinctive features

of the upper deck (visible from above) without making it

clear what belongs to one, what to the other.

The conception of the Plan of St. Gall is highly superior

in this respect. In his layout of the transept and the presbytery

of the Church (fig. 99), where the component parts of

several levels are shown in simultaneous projection, the

author defines the interrelationships so clearly that the eye

finds no trouble in establishing that the presbytery is

raised above the level of the transept by seven steps and

that the vaulted arms of the ambulatory corridor crypt lie

beneath that level. He makes it unequivocally clear that the

longitudinal arms of that crypt run along the outer surface

of the choir walls and terminate in a transverse arm that

gives access to the tomb of St. Gall. He leaves no doubt

about the length and width of these arms.

With all of this I do not mean to imply that a Roman

architect might not have been equally proficient. To place

this entire problem into proper historical perspective the

reader must here be reminded of the fact that the Forma

urbis was not only drawn at a considerably smaller scale

(1:240) than the Plan of St. Gall (1:192), but also that it

included buildings of exasperating constructional complexity

and most important of all, that it was never meant

to serve as a building plan to be used in construction; it

was more in the nature of a real estate record. Considering

its scale and its purpose, it renders with admirable conceptual

simplicity the layout of such complex structures as

the Colosseum and the Theater of Marcellus.[258]

For modern plans and descriptions of the Theater of Marcellus see

Calza-Bini, 1953, 1-43; Bieber, 1961, 184-85 and Ward Perkins in

Boethius-Perkins, 1970, 186-88. For the Colosseum see Durm, 1885,

342-45; Colagrossi, 1913; and Ward-Perkins, op. cit., 221-24. A full

bibliographical record for each building will be found in Platner, 1929,

513-15 (Marcellus Theater) and 6-11 (Amphiteatrum Flavium).

I.12.5

LACK OF SPECIFIC INFORMATION

CONCERNING BUILDING MATERIALS

The Plan does not give explicit instructions for the materials

with which the individual buildings were to be constructed.

All installations are rendered in a uniform line,

and this line may stand for a masonry wall, a wooden fence,

the outlines of a bench or a table, or a seedling bed in the

vegetable garden. It is fairly obvious, however, both in

view of the peculiarity of their design and the prevailing

building customs, that stone construction was envisaged

for the nuclear claustral structures: the Church, with its

columnar order, its circular towers, and apses; the Cloister,

with its round-arched galleries and portals, as well as the

monastic buildings directly contingent to the Cloister; the

Dormitory, the Refectory, and the Cellar. To these should

be added the complex that contains the Novitiate and the

Infirmary with its round-arched cloister walks and round-apsed

chapels, and, finally, the Abbot's House with its

arcuated porches. Whether masonry can be postulated for

any of the remaining structures is a controversial question

to which special attention will have to be given later in this

study.[259]

I.12.6

DIFFERENTIAL ATTENTION IN THE

RENDERING OF DOORS

An interesting case of discrimination between buildings of

lesser and greater importance can be observed in the

rendering of the doors. Throughout the whole expanse of

the Plan the location of a door is designated by two short

strokes intersecting the walls at right angles. In buildings

of major importance, the wall line stops as it reaches the

first crossbar and takes a fresh start in the center of the

opposite bar

lesser rank in the religious or social hierarchy of the

monastery the wall runs through as a continuous line, and

the crossbars simply intersect it

of course, a faster way of rendering, which the draftsman

first substituted sporadically for the more exacting manner

as his hand got tired in the tracing of individual structures,

and then consistently as he turned from the primary to the

secondary buildings. In the Church (fig. 55), the most

important building of the Plan and the first to be traced,

there is only one instance of the abbreviated form: one of

the passages in the barrier that connects the penultimate

freestanding pair of columns, significantly enough, in a

place where the line straddles the seam of two connecting

sheets of parchment. In the atrium west of the Church there

are two more cases: the two openings in the wall that connect

with the passages of the two towers. There is none in

the Abbot's House (fig. 251), nor the Outer School (fig.

407), and only one in the House for Distinguished Guests

(fig. 396), one of the entrances to the stables of the horses.

48. MARBLE SLAB OF CLAUDIA OCTAVIA

PERUGIA, MUSEO ARCHEOLOGICO NATIONALE DELL' UMBRIA

[courtesy Soprintendenza alle Antichǐtà dell' Umbria]

The slab displays the plan of a sepulchral monument (large building, right), and the house of its guardian (smaller building, left). The third

plan (in center, and at top) shows the basement of the guardian's house. Walls are rendered by two parallel lines; doors are indicated by

continuation of the outer line or by interruption or bending of both wall lines. Stairs are indicated varyingly as a sequence of parallel lines or as

two converging lines. The dimensions of the room are designated by Roman numerals. Gatti, who analyzed the plans, came to the conclusion

that they were drawn in three different scales: that of the sepulchral monument at the scale of 1:84; those of the guardian's house at the scales

of 1:140 and 1:230, respectively (see Carettoni ET AL, 1960, I, 210).

through the claustral structures, and thereafter the abbreviated

method of rendering becomes routine. The first

building drawn entirely in this style is the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers (fig. 392). In some of the more

important guest and service buildings, such as the Great

Collective Workshop (fig. 419), and the House for Horses

and Oxen and Their Keepers (fig. 474), the two methods

are judiciously combined: the disrupted line for the principal

entrances, the undisrupted line for the secondary

doors. In the buildings to the east of the Church the continuous

line is standard; the disrupted line, the exception.

And in all of the buildings that lie to the west of the Church,

there is only one occurrence—obviously accidental—of the

disrupted line, in the House for Sheep and Shepherds and

Their Keepers.

I.12.7

THE PLAN IN HISTORICAL

PERSPECTIVE

The method of rendering used in the Plan of St. Gall is

closely related to that displayed in the great marble plan

of the city of Rome made under Emperor Septimius

Severus, and belongs to the same historical tradition of

rendering. Functionally, these two plans have little in

common. The Forma urbis delineates an existing condition,

the layout of a grown city. The Plan of St. Gall does not

define how it is, but how it should be. These differences,

however, had little, if any, effect on the manner in which

the two plans were rendered.

Like the architects who designed the Forma urbis, where

wall thicknesses are indicated in a few judiciously selected

categories of building, the author of the Plan of St. Gall

would have been fully capable of rendering the walls of his

buildings in full thickness. Like the former, he chose not

to employ this method for the same reason an architect

today would use single line projection instead of double line

projection for the rendering of walls, namely, the complexity

of his subject and the smallness of the scale in which

it was drawn. There is good evidence that the Forma urbis

was still in place on the walls of SS. Cosmas and Damian

in the Carolingian period,[260]

and thus could have been seen

by the Frankish emperors who visited Rome and the

architects who traveled in their following. Moreover, there

are more substantive reasons for thinking that the designer

of the Plan of St. Gall was familiar with the layout of the

city of Rome.[261]

If it was the purpose of the Plan of St. Gall to depict on In this plan dating from the New Kingdom, wall thickness is

a single spread of parchment the layout of the buildings and

furnishings of a paradigmatic medieval monastery, it would

be hard to improve upon the method of rendering that the

designer chose in order to accomplish this task. One of the

most successful features is the freeness and flexibility of

mind with which the designer switches from the rendering

of the ground floor to the rendering of an upper level—

49. EGYPTIAN HOUSE PLAN

rendered by parallel lines.

suggested such action—and chooses to explain the nature

and function of the repressed story with the aid of an

explanatory title. To do it differently would have required

supplementary drawings. Even from a purely technical

point of view the Plan of St. Gall is a highly sophisticated

document. It tells the story of a very complex architectural

situation with ingenious simplicity. One of the designer's

overriding preoccupations was the retention of clarity in

the over-all appearance of the settlement. He was detailed

where attention to detail was imperative in the light of

function; but he did not hesitate to omit almost entirely

such features as stairs where their delineation would have

impaired the clarity and easy readability of the primary

elements of his drawing.

With all its medieval idiosyncraises, the Plan of St. Gall

has a surprisingly modern flavor. Its analytical precision

and clarity compare favorably with any modern site plan

drawn at a comparable scale. The designer did not hesitate

to enliven his plan with elevations in a few places, where

this method promised to convey his thoughts more fully;

but in departing in this manner from his general mode of

rendering he proceeded with a deep sense of discrimination

and with conspicuous self-restraint. Above all he carefully

resisted any temptation to indulge in architectural pictorialism.

This quality is strikingly revealed if one compares

the Plan of St. Gall with the twelfth-century plan of the

Waterworks of Christchurch Monastery at Canterbury

(fig. 52) where everything is shown in elevation as in a

child's drawing.

50.B FLAVIAN AMPHITHEATRE (COLOSSEUM)

PLAN

ROME, ANTIQUARIUM COMMUNALE DEL CELIO

[after Durm, 1885, 344, fig. 310]

This composite plan of the Colosseum shows four different levels.

50.A FORMA URBIS ROMAE

ROME, ANTIQUARIUM COMMUNALE DEL CELIO

[after Carretoni, 1960, vol. II, pl. XXIX]

These fragments show the seating arrangement of the Colosseum as if

seen from above.

COMMENT:

for figure 50.A and FORMA URBIS ROMAE, generally

The illustration, using the lower portion of the graphic scale graduated 0-100

metres, scales 186 metres on its major axis. This compares with 187.5 metres

(615 feet) commonly given for the length of the Colosseum, a variance of less

than 1 percent between present day measurements and the sculptured mural

version that records the measurements of engineers at a time when the plan

was cut in place in stone.

FORMA URBIS ROMAE stands as a remarkable demonstration of the state of

the art of drawing, with knowledge not only of measure, but the skill of taking

measurements and translating these measurements precisely into a graphic

configuration of great accuracy. Far exceeding any practical function, such as

a cadastral plan for administrative purposes, must have been its effect on the

mind of the beholder. The impact on a viewer of the plan of Rome, incised in

stone for all time, spread across a wall 59 feet wide and rising, on its base,

to 56 feet, could not but impress even the most sophisticated Roman. For the

visitor from beyond the hills of Rome and from lands afar, the effect could

not have been less than overwhelming.

The conjecture is tempting, that the sculptural mural map may have been

seen, if not by the great Carolus himself, by learned men of his court and

soldiers of his entourage in the course of their duties in Rome.

A record of achievement, symbol of law and order and authority, invincible

and eternal, it seemed without doubt, and a fitting inspiration as well, for an

emperor and his sometimes loyal and always ambitious followers.

The comparative scale, included with the illustration, compares the scale of the

sculptured plan above, the line (40 cm), with the actual "on the ground"

measure (100 m), below. The ratio, 41.7 cm. to 100 m, is almost 1:240.

The ratio between the scale of illustration 50.A and the Colosseum computes

at about 1:951.7 (derived from the relation between 19.7 cm = 187.5 m).

Thus the illustration is about ¼ the size of the rendering of the plan on the

sculptured wall.

1/952/1/240 = 240/952 = 1/3.98 [or ¼]

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||