The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. | I. 10 |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I. 10

HOW THE PLAN

WAS DRAWN AND ASSEMBLED

I.10.1

NUMBER OF SHEETS & SEQUENCE IN

WHICH THEY WERE SEWN TOGETHER

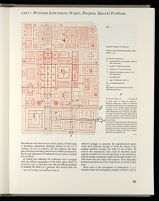

The Plan is drawn upon a piece of parchment composed of

five separate sheets of calfskin (not lamb or goat, as was

formerly believed)[196]

and sewn together by threads of gut

(fig. 24, nos. 1-5). The drawing is on the softer inner side

of the skins, which show traces of scraping and are slightly

roughened by pumice stone. The edges are irregular, most

markedly so on the right-hand side of the Plan, where the

skins did not yield sufficient surfaces to allow the corners

to be squared.

The largest over-all dimensions of the Plan are 30¾ × 44 3/16

inches (78 × 112 cm.).[197]

The original dimensions are more

likely to have been in the neighborhood of 32 × 46 inches.

Konrad Hecht, who engaged in some interesting speculations

on this subject, estimates the over-all shrinkage to

which the parchment was subjected in ten centuries of

aging to amount to 5 to 6 percent of the original surface

area.[198]

Even today the dimensions vary slightly in response

to changing humidity conditions.[199]

The distribution of the monastic buildings over the five

component sheets of the Plan is as follows: sheets 1 and 2

accommodate the Church, the Claustrum, the guest and

service structures to the north of the Church as well as in

the corner between the Church and the Claustrum; sheet

3 accommodates the service structures south of the Claustrum;

sheet 4, the Novitiate and the Infirmary, the

Cemetery, and all the other structures to the east of the

Church; sheet 5, the stables for the livestock and all the

other agricultural service structures to the west of the

Church.

The sequence in which the sheets were sewn together

can be reconstructed from the manner in which they overlap

each other. First, sheet 2 was attached to sheet 1 from

below. Next, sheet 3 was sewn onto sheets 1 and 2, again

from below. Then sheets 4 and 5 were sewn to sheet

group 1, 2, 3 from above (fig. 24, nos. 1-5).

The material used for threading the seams is a natural

uncolored gut identifiable as such even on the facsimile

(in contrast to the green pieces of thread that were used

at a relatively recent date to patch together certain sections

along the former folding lines of the Plan where the parchment

was torn). A closer look at these seams suggests that

not all of them were stitched by the same hand. The seams

that hold sheets 1, 2, and 3 together are made in short

stitches and take a surprisingly swerving course, while the

seams through which sheets 4 and 5 are attached to the

sheet-group 1, 2, 3 follow a very straight course and are

sewn in longer and more elegant stitches.[200]

There is clear evidence that sheets 1, 2, and 3 were sewn

together before the drawing was started, since the lines

of the drawing all run in a continuous motion over the

edges of these sheets, from the higher lying sheet on to

the lower one. Where sheet 1 overlaps sheet 2 (fig. 25,

the lines must have been drawn in the direction from sheet

1 to sheet 2 since the quill did not smear, as it would

inevitably have done had the stroke been conducted upward

from sheet 2 over the edge of sheet 1. Where sheets

1 and 2 overlap sheet 3, again, the lines were drawn from

the higher sheet (1 and 2) to the lower lying one (3). For

more detail I refer the reader to the explanatory caption

of figures 26-28.

In general the draftsman moved his line in a continuous

stroke across seam and edge, but in some cases he stopped

at the edge of the higher sheet and started a new stroke on

the lower sheet, so that the impact of the quill with the

edge of the higher sheet bent the start of his line into a hook

(fig. 28 and 29).

The ductus of the line shows all of the possible effects of

the encounter of the quill with the seam and the edge of

the sheets: a slight tendency for the ink to spatter at these

critical points, a minute disruption of the straightness of the

line as the quill takes a slight leap from the edge of the

upper skin to the surface of the lower, and a minute

tendency to swerve at this point. Nowhere in sheet-group

1, 2, 3 is any part of the drawing covered up by an

overlapping margin of the adjacent sheet—clear evidence

that this group of sheets must have been sewn together

before the drawing was started.

Sheets 4 and 5 must have been drawn separately and

sewn onto sheet-group 1, 2, 3 only after the latter had been

completed (fig. 24). This can be inferred from the fact

that a number of lines on sheets 1 and 2 are covered up by

the overlapping margin of sheet-group 4, 5. Thus, for

instance, the easternmost portion of the eastern apse of the

Church (fig. 30) is completely drawn out on sheet 1, but

covered up by the overlapping edge of sheet 4, as one can

see when lifting the overlapping edge from the front side

of the Plan. Similarly, the ascending stroke of the letter

A of the great axial inscription AB ORIENTE IN OCCIDENTEM

. . . appears on both the covered portion of sheet 1 and the

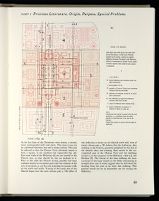

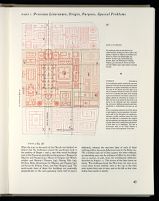

24.B PLAN OF ST. GALL

EXAMINATION OF CONDITIONS WHERE LINES OF THE

DRAWING CROSS OVERLAPPING SEAMS

A key plan for figures 25 through 32

The "window" areas of the Plan shown on opposite page define the

location of those areas of the drawing which are examined in detail

in figs. 25 through 32. In all these places the scribe's lines

cross seams and overlapping edges, thereby revealing much about the

sequence in which the five component sheets of parchment were

assembled.

Figs. 33-40 attempt to illustrate the eight successive stages of the

growth of the tracing. The interpretation is based primarily on two

types of observation:

1. The progress of work as inferred from the manner in which the

lines are drawn in critical areas where they run across the

overlapping margins of two joined pieces of parchment (figs. 25

through 30).

2. The detection of certain angular distortions in the layout of

buildings, which we attribute to a mainly inadvertent shift in the

relationship of overlay and original, incurred in the process of

tracing.

The draftsmanship of the Plan adheres to a prevailing concept of

rectangularity in its overall design as well as in the inter-relation of

many internal systems of rectangularity. Even unaided, the eye is

able to discern deflections between adjacent systems, in several places.

We are convinced that these could not have occurred in the

construction of the original drawing from which the Plan was copied.

The draftsmanship of the Plan of St. Gall exhibits a high degree of

manual expertise, but the Plan was traced and therefore not

dependent on any mechanical aid. The original scheme, by contrast,

must necessarily have been constructed. Large and complex as it was,

its author could not possibly have accomplished the orderliness and

scale correctness by which it was characterized without mechanical

aids, such as graduated straightedges, T-squares and or other similar

devices, the use of which would have precluded angular deviation.

The rectangular distortions in the Plan, and its deflections from the

square, we are convinced, were caused by difficulties encountered in

the act of tracing, an operation far from simple in a time when aids

such as light boxes, tracing paper, and adhesive tape for securing

both the original parchment and the overlay parchment with absolute

precision, were unknown.

observed at the western end of the Church (fig. 31). Here

the porch was drawn out in its entirety on sheet 2 before

sheet 5 was sewn onto it from above. Sheet 5 also covers

the lower portion of the word habebit in the porch inscription,

not to the extent, however, of having to be redrawn

on sheet 5.

From these conditions it follows conclusively that the

drawings of sheet-group 1, 2, 3 must have been completed

before the sheets 4 and 5 were added to this group.[202]

(For

additional evidence, see extended caption of fig 30.)

There is no conclusive evidence to show that sheet 5 was

drawn at a later stage than sheet 4. But it is obvious that

the buildings on sheet 4 are of greater importance for the

life of the monastic community than the service structures

shown on sheet 5, and therefore would command a higher

priority in attention. Moreover, the draftsmanship of

certain buildings on sheet 5, exhibiting signs of fatigue as

will be shown in a later place, suggests that this portion

of the Plan was the last to be drawn.

As the edges are very irregular, the dimensions vary from place to

place. The length varies between 44 3/16 and 44 inches (112.3 and 111.8

cm.); the width between 30¾ and 28 11/16 inches (78.2 and 73 cm.).

I owe this observation to my graduate student Anita Merrit, who has

considerable experience in sewing. It looks very much as though some

dissatisfaction had arisen in the draftsman's mind over the coarse manner

in which sheets 1, 2, and 3 were sewn together, resulting in an improved

performance where sheets 4 and 5 are attached.

The connecting portions of the semicircle of the eastern paradise,

however, were drawn after the sheets had been attached to each other.

The are does not continue under the margin.

Hecht, 1965, 168ff questions this conclusion without convincing

evidence. Cf. my counterargument in Horn and Born, 1966, 288, note 20.

I.10.2

SUCCESSIVE STAGES IN TRACING

THE PLAN

Certain peculiarities in the drawing tell us a good deal

about the working procedures of the draftsman and about

the sequence in which the buildings were traced. It is quite

obvious that the draftsman was right-handed, and that he

made his copy by tracing the successive portions of the

drawing from left to right and from top to bottom. Our

analysis of the manner in which the quill responded to the

hurdle of the seams and edges of the overlapping margins

of the respective sheets left no doubt on this score (see the

extended captions of figs. 26-29). There is no dearth of

further confirmatory evidence. The distinctive marks of

the first impact of the ink with the parchment as the quill

touches the skin, and the tendency of the ink to diminish in

bulk as the line stretches out and to trail into a thin tail as

the quill is lifted can be observed in scores of places. Also

to be noticed in this connection is the fact that the ductus

of the draftsman's line was relatively straight and sure when

he started his work on the left-hand side of the skin and

remained so as long as his hand retained a firm base. But it

developed a tendency to swerve as his hand reached a

point where it began to lose its rest, as it was bound to do,

at the lower right-hand corner of the sheet. Clear evidence

of this is: the Bake and Brew House for Distinguished

Guests (the last to be drawn of the buildings that lie to the

north of the Church); the Medicinal Herb Garden (the

last installation to be drawn on sheet 4); and the houses for

the cows and foaling mares and their keepers (the last to

be drawn on sheet 5).

The primary clue to identifying the sequence in which

the buildings were drawn is the number of shifts in the

relative position of original and overlay that occurred in

PLAN OF ST. GALL

25.A OVERLAPPING EDGES OF SHEETS 1 AND 2 ACROSS HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS AND THE MONASTERY CHURCH

Sheet 2 was sewn to sheet 1 from below, a procedure that can be demonstrated by the scribe's lines, which run in continuous motion over the

edges from the higher-lying to the lower sheet, and from left to right east to west). The design reveals extraordinary skill of draftsmanship.

The line crosses the seam in a continuous motion, wherever the quill finds free passage in the interstice between the gut, and drops from the upper

to the lower-lying sheet with almost no displacement or tremor. Nowhere in sheet group 1, 2, 3 is a part of the lower sheet covered by the

overlapping margin of the upper sheet—clear proof that sheets 1, 2, 3 were sewn together before the tracing was begun.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

26. DETAIL OF FENCE, MONKS' REFECTORY TO GREAT COLLECTIVE WORKSHOP

Drawn from left to right, the line stops on reaching the seam. It starts out again immediately

behind the seam and runs in smooth and continuous motion from sheet 1 over its edge down to

sheet 3.

27.A COVERED PASSAGEWAY, MONKS' KITCHEN TO MONKS' BAKE & BREW HOUSE

The upper line crosses seam and edge of sheet 1 in continuous motion. The lower line stops on

reaching the protruding portion of the gut, makes a fresh start behind it, and runs smoothly

across the edge onto the lower surface of sheet 3, it makes a minute jump westward.

27.B A CORNER OVERLAP

This interesting detail shows the corner at which sheets 1, 2, 3 overlap each other, clearly

revealing that sheets 1 and 2 must have already been joined before sheet 3 was attached from

below.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

25.B

CHURCH

25.C

MONKS' CELLAR AND LARDER. CONDITION AT FENCE TO WEST

In drawing the choir screen, which connects the second pair of nave columns transversely, the draftsman had to guide his quill lengthwise over

the protruding ridges of the seam, an ennervating experience which he later tried to avoid by moving the line away from the seam when he

encountered similar conditions in drawing the west wall of the Cellar.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

28. HOUSE OF COOPERS AND WHEELWRIGHTS. DETAIL

At A and C the line runs smoothly and continuously over seam and overlapping margin of sheet

1 down to sheet 3. At C the line stops at the edge of sheet 1 and starts fresh on the lower-lying

sheet 3, being bent into a hook by the impact of the quill with the edge of sheet 1.

29. HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN. DETAIL

The lines are drawn from left to right smoothly across the seam, and in one case (third line from

bottom), smoothly over the edge of sheet 2; but in all other cases the line stops at the edge of

sheet 2 and makes a fresh start on sheet 3. The edge of the overlapping sheet bends the start of

the line into a hook.

PLAN OF ST. GALL MONASTERY CHURCH, WESTERN APSE AND PARADISE

30.

The two easternmost portions of the apse are completely drawn out on sheet 1, but covered up by the overlapping edge of sheet 4—clear proof

that sheet 4 was not attached to sheet group 1, 2, 3 when the Church and the Claustrum were drawn. By inspecting the original, one would

observe that the rounding arcs of the apse on sheet 1 extend beyond the seam by which sheet 4 is fastened to sheet group 1, 2, 3.

which cannot have been part of the original concept.[203]

A left-to-right and top-to-bottom movement frequently

referred to in the following stages of growth for tracing the

Plan is not exclusively controlled by convention in direction

of writing. In tracing, top-to-bottom issues mainly from

the need to avoid smearing ink. (Writing executed in clay or

wax, as in many ancient languages, could be from right to

left). The tracer is influenced by long established writing

convention, but he is not governed by it. He traces where it

is most convenient, moving freely from area to area according

to the matter he is working on. Drying time of the

writing fluid used has much to do with the tracer's sequence.

On completing a series of lines in one area he

relocates, usually to a safe distance removed from lines still

wet, then shifts back to the previous part of a different part.

Thus while tracing sequence may generally be left to right,

discontinuity is a characteristic in the Plan. When drawing

a set of lines perpendicular to another set, a draftsman

prefers to turn the sheet roughly 90° or to shift his position

similarly, rather than draw from the same position—

pushing the pen or pulling it toward him is avoided.

However each method is used. The one adopted, extremely

a matter of personal choice, is related to the tracer's temperament,

his experience, kind of materials, and equipment

used, lighting conditions and other matters. If the

Plan abounds with inexplicable details of execution it is

because tracing, like drafting, is a highly subjective skill,

defiant of rational prediction or logical deduction, except

in a very general way. In offering this study and analysis of

the tracing stages of the great Plan, the authors are humble

in mindfulness of the problem and respectful of the scribes

and draftsmen who made it.

PLAN OF ST. GALL PORCH GIVING ACCESS TO WESTERN ATRIUM OF CHURCH

31. The last word of the explanatory title of the Porch, HABEBIT, is

partially covered by the overlapping margin of sheet 5, which was

sewn onto sheet group 1, 2, 3 from above. The Porch had been drawn

in its entirety on sheet 2 before sheet 5 was sewn onto it.

PLAN OF ST. GALL. DETAIL, BAKE AND BREWHOUSE OF THE HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS (NORTH OF FENCE)

AND HOUSE FOR HORSES AND OXEN (SOUTH OF FENCE)

32. The corners of these two buildings are partially covered by the overlapping margin of sheet 5, which suggests that these buildings were drawn at

a time when sheet 5 was as yet not attached to sheet group 1, 2, 3.

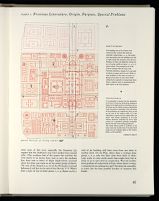

33. STAGE 1 OF TRACING

The draftsman faces the Church from the

west and traces the eastern parts of the

Church and Dormitory with their subsidiary

buildings from left to right.

Sheet group 1, 2, 3, sewn and assembled for

the draftsman to work on, is shown with

color tint. Pale red lines indicate Plan not

traced at this stage. Sheets 4 and 5,

illustrated in subdued line, are incorporated

as part of the Plan later as shown in

figure 40.

COMMENTS

In our study of the Plan of St. Gall, over a long

period of years, it has constantly been necessary

to have a line, or base of reference, from which

to take measurements or from which to relate

one element of the Plan with another. The north

row of columns of the Church nave appears to

offer the most satisfactory remaining evidence

on which to establish a kind of base or reference

line. It will be seen on the facsimile reproduction

(see p. 3, n17) that a line drawn between the

center of the most easterly column W (fig. 34) of

the north row of columns establishes probably

the "strongest" line on the Plan. This line,

Z-Z, is shown extended to the border, top and

bottom. Nine columns intermediate between

these two extremity columns E-W, deviate but

slightly from this imaginary line. This line,

incidentally, contains the longest clearly defined

measure of the Plan.

The reference to 300 feet, length of the Church,

elsewhere on the Plan, is not so explicit. The

corresponding row of columns on the south side

of the nave deviates only very slightly more from

a similar line exactly parallel to the line of the

north row. The longitudinal axis of the Church

has been taken as a line midway between and

parallel to these two rows of columns and is

shown on the drawings as a ruled dot-and-dash

line, Y-Y. It is a useful reference line from

which, visually, to detect the presence or absence

of symmetry.

In the following analytic remarks the east-west

geometry of the nave serves as a base from which

deflections or angular relationships are referred.

The axis of the Church has been taken as an

axis of ordinates. Because the north row and the

south row of columns (the piers of the crossing

square are included in the column count) are so

slightly affected by aberrations in tracing, it is

likely that they were among the first items to be

drawn by the draftsman and were completed

(fig. 33) prior to shifting movements made later,

consciously or inadvertently (see note, pp. 48,

49).

As for a convenient reference line (X-X) exactly

at right angles to the nave geometry, the north-south

walls of the Dormitory are satisfactory,

although a wobbly condition toward the south

near the Refectory is noticeable and suggests

that the draftsman was beginning to have tracing

troubles which were to plague him intermittently

from there on to completion. The pair of

north-south walls of the Cellar likewise is

normal to the control geometry of the nave.

STAGE 1 (fig. 33)

Facing the Plan from the west the draftsman started the

drawing on sheet-group 1, 2, 3 with the eastern end of the

Church, moving from left to right and from the top downward

as far as the second pair of nave columns, then in a

southerly direction to the Annex for the Preparation of

the Holy Oil and Bread, the Monks' Dormitory and its

auxiliary buildings, until the south walls of the Monks'

Privy and the Monks' Laundry and Bathhouse were

reached. The irregular course of the lines discloses that

the draftsman worked without instruments, completing

each individual area before moving on to the next one. As he

traced the beds in the southern part of the Dormitory [3],[204]

the overlay apparently slipped slightly to the left about one

module,[205]

thus extending this building a little more to the

south than it was meant to be.

The discussion that continues is concerned with tracing

and drafting procedure, with countless movements of hand,

body and pen, which can never be reconstructed with

certainty or uncovered by intellectual process.

The remarks, stages 2-8, with comments in captions for

figures 33-40, are pursued as a valid component of inquiry

into genesis—copy or original?

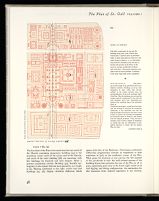

34. STAGE 2 OF TRACING

Just before the scribe draws the south wall

of the Dormitory, a shift occurs between

original and overlay, causing an angular

deflection between Dormitory and Refectory,

which is transmitted to Cloister Yard, Cellar,

as well as parts of the Church from column

5 westward.

LEGEND

Z prime reference nave columns, north row

(line continuous)

y line parallel to Y, Z

Y parallel to Z axis of Church and reference

ordinate (line dot-and-dash)

X reference co-ordinate, normal to Y and Z

(line continuous)

a, c line deflected by angle from reference

ordinate Y(Z) (line dotted)

δ angle of deflection from ordinate Y(Z)

δ′ angle of deflection in excess of δ

[applies to figure 35, page 44]

NOTE

Continuous line system is square with the nave

geometry, i.e., continuous lines are either

parallel or perpendicular to the axis of the

Church.

Dotted line system is square with the angle of

deflection.

STAGE 2 (fig. 34)

As the last lines of the Dormitory were drawn, a second,

more consequential shift took place. This time it was not

in a sideward direction, but was a rotary motion. This may

be inferred in that the Cloister Yard, obviously meant to

form a square, is not quadrate but trapezoidal (fig. 36).

East-west walls of the Refectory [6] are not parallel to the

Church axis, as they should be, but are inclined to it.

Prior to this shift the Church tracing possibly had been

confined mostly to its eastern parts and the columns of the

nave (comments, p. 47) but not including its exterior walls

on the north and south. Tracing of the south side of the

Church began near the nave column pair 3. The effect of

this deflection is shown on the Church north wall, west of

(near) column pair 4. We believe that the draftsman, after

working on the Church, generally peripheral to the area of

the chancel, altar, and crossing, then moved to the uncompleted

part of the Cloister Yard and the buildings

around it, in the sequence of the Refectory, cellar [7], and

Kitchen [8]. The ductus of the lines defining the stave

curvature of the large barrels in the Cellar (decreasing in

strength from east to west) suggests that he still faced the

drawing from the west as he drew this building. This

position would not be an impossible one for tracing the

Refectory.

35. STAGE 3 OF TRACING

After Church and Claustrum were completed the draftsman rotated the skins

counterclockwise by 90 degrees and traced the buildings to the north of the Church,

in the sequence: Abbot's House, Outer School, House for Distinguished Guests,

without correcting the deflection caused by the shift that occurred at the end of Stage 1.

A number of further shifts occurs as this latest portion of the tracing is finished.

STAGE 3 (fig. 35)

The draftsman is positioned to look south. He draws in

sequence: Abbot's House [14,13], Outer School [12],

House for Distinguished Guests [11], and Kitchen, Bake

and Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests [10]. The first

buildings in the sequence have their east-west walls parallel

to the nave geometry. However, the third building [11], its

south half in a deflected position, its north side with a

curious bent wall alignment, may imply a struggle by the

draftsman to correct the angular shift and return to

parallel position. In the fifth building [10], its east-west

(south) wall is deflected to exceed all other angular deviations,

save one, the east-west walls of building [40]. That

he traced these houses facing the Church from the north is

disclosed by the ductus of a good many lines which

decrease in strength as they are drawn from left to right and

from the top to the bottom. The shift between original and

overlay had moved the Abbot's House slightly to the east of

its proper position. The draftsman compensated for this

displacement by drawing the gallery, connecting the

Abbot's House with the northern transept of the Church,

on a slightly slanted, rather than rectangular, course to the

nave geometry.

36. STAGE 4 OF TRACING

The draftsman shifts his skin back into its

original position working from left to right in this

sequence: Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers [31].

House for Coopers and Wheelwrights and

Brewers' Granary [39], Drying Kiln [29],

Kitchen, Bake, and Brewhouse for Pilgrims,

Paupers [32], and house for Horses and Oxen

and their Keepers [33]—again without correcting

the shift.

STAGE 4 (fig. 36)

When the tract to the north of the Church was finished we

believe that the draftsman rotated the parchment back to

the position of Stages 1 and 2, and then traced buildings

west of the Claustrum probably in this sequence: Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers [31], House of Coopers and Wheelwrights

and Brewer's Granary [39], Drying Kiln [29],

Kitchen, Bake, Brewhouse for Pilgrims and Paupers [32],

and house for Horses, Oxen, and their Keepers [33]. The

north-south lines of these five buildings are practically

perpendicular to the nave geometry (west wall of [32] is

deflected), whereas the east-west lines of each of these

buildings follow the same deflection found in the Refectory.

The condition (one set of lines square, the other oblique),

an interesting one, may be evidence of effort by the draftsman

to recover, in part, from the troublesome deflection

described in Stages 1, 2. The ductus of the lines leaves no

doubt. The draftsman faced the Plan from the west as he

traced these houses (thicker ends at the top as the lines

were drawn from east to west, and at the left as they were

drawn from north to south).

37. STAGE 5 OF TRACING

The draftsman swings the skins clockwise by 90 degrees and traces the buildings

that lie to the south of the Claustrum by facing the monastery from the south.

The alignment of these buildings discloses that the shift had been detected and

corrected. The deflection of the south walls of the buildings [28, 27] is similar

to the deflection of the north wall, east end of the Church, line C, figure 34.

STAGE 5 (fig. 37)

When the tracing had reached the stage defined in fig. 36,

the draftsman had become aware of the fact that overlay

and original had moved, and he decided to realign the two

skins. He readjusted the sheets, thus bringing the buildings

south of the Claustrum back into their original position (not

entirely, but nearly so), necessitating a deflection of the

line that connected the south wall of the Drying Kiln

(traced before readjustment) to the corresponding south

wall of the Mortar House [28], the deflected line continued

eastward as the south wall of the Mill [27], to its north-south

wall on the east, at which point it was restored to

normal position and in alignment with the south wall of

the Workshop Annex [26]. The other buildings of this

group appear to have been drawn, generally, from left to

right and from top to bottom in this sequence: Monks'

Bake and Brewhouse [9], Mortar House [29], Mill House

[27], Great Collective Workshop [25], with Annex [26],

and Granary [24]. These buildings have their east-west

and north-south walls perpendicular to each other and are

square with the nave geometry.

STAGE 6 (fig. 38)

The sequence of tracing the buildings on sheet 4 (which we

presume to have been separately drawn and completed

before it was sewn on to sheet-group 1, 2, 3) is difficult

to establish. The most functional approach for the draftsman

would have been to face this section of the Plan from

the east, since this would keep the bulk of the original away

from his body. But tracing the circles of Hen and Goose

Houses [23, 21] required a complete rotation of the skins;

38. STAGE 6 OF TRACING

The buildings east of the Church were

traced on sheet 4 before this sheet was

attached to sheet group 1, 2, 3. The draftsman

apparently drew the buildings from left

to right, facing the monastery from the east.

Evidence of shifts and deflections during the

act of tracing, visible on sheets 1, 2, 3, 5, is

almost absent. The prolonged axis of the

Church coincides with the axis of the

Novitiate-Infirmary complex [17], the walls

of which are square with the axis. Walls of

other buildings on this sheet are square, or

deviate from square no more than would

ordinarily be expected in tracing large sheets.

Sheet 4 adheres closest to perpendicularity

with respect to the nave geometry.

suggest that the draftsman may have worked from several

sides. (The southern line of the square that encloses the

cross seems to be drawn from west to east; the northern

line, from east to west.) A slight displacement occurred

when this sheet was sewn on to the center group of sheets.

The axis of the Chapel [17a, b] of the Novitiate [17c] and

Infirmary [17d] lies on the axis of the Church, Y-Y. Where

sheet 4 laps on top of sheet group 1, 2, 3, (figure 24.A), a

total of six building wall lines cross from one sheet to

another sheet. On the Plan, where sheet 5 overlaps sheet

group 1, 2, 3, only two lines cross from sheet to sheet.

Laps made at some north-south lines might have had as

many as 50 or more lines in conjunction. Was the troublesome

problem of conjunction of lines, where sheets overlap,

a consideration in making the copy? Certainly the assembly,

as made, has the least possible number of crossover line

breaks.

39. STAGE 7 OF DRAWING

Like their counterparts in the east the

buildings lying west of the Church were

traced upon a separate piece of parchment

(sheet 5) before this sheet was sewn on to the

center group of sheets (1, 2, 3). The draftsman

faced the monastery from the west as

he drew this portion of the Plan. In the

course of tracing, considerable clockwise

twist took place. The greatest deviation from

square with the nave geometry is exhibited

in the lower right hand corner (southwest).

STAGE 7 (fig. 39)

The last sheet of the Plan to be traced was the tract south of

the Church containing anonymous building [34] in the

northwest corner south of the access road of the Church,

and south of the road, building [38], use uncertain, with

five buildings for livestock and their keepers. Sheet 5

presents perplexing interest. Building [34], literally rectangular,

is also square with the nave geometry, as it ought

to be. Moving southward to the right, access road and

buildings [35, 38], display clockwise deflection which

agrees with that of the Refectory. Continuing southward,

deflections progressively increase in magnitude to their

maximum in [40], in the southwest corner of the Plan.

What gains the attention as one surveys the full expanse

of the parchment is this: the well ordered pattern of the

building layout that pervades the rest of the Plan in all its

parts, apparently goes awry in the lower right corner in an

odd dipping and tilting configuration. An explanation for

this departure from ordered regulation is not obvious.

40. STAGE 8 (FINAL) OF DRAWING

Sheets 4 and 5 have been attached to sheet

group 1, 2, 3.

for LEGEND see figure 34

Z prime reference, nave columns, north row

(line continuous)

Y parallel to Z (line dot-and-dash)

y parallel to Y, Z (line continuous)

X reference co-ordinate, normal to Y, Z

(line continuous)

a line deflected by

δ angle of deflection from Y, Z.

Σδ accumulated deflection

NOTE

Short dash line and X-dash line are lines

deflected greater than δ

It is reasonable to assume that the parchment,

as we know it today, has always been irregular in

shape on the right (south on the Plan), that is,

the shape was not altered by some unexplainable

local contraction or shrinkage. Top and bottom

of the parchment are, respectively, about 92 and

93 per cent of the median width. It is also

reasonable to assume that the original Plan was

drawn with normal consistency in all parts

without distortion (including the lower right

corner) on a parchment generally rectangular

like the left side of the existing parchment.

The Goose House posed no problem to the

tracer since the circular form of its plan fitted

neatly into the irregular shape at this location

(sheet 4 of the asembly).

At the lower right of the parchment there was a

different condition. Buildings 37 and 40, both

rectangular in plan, rather than circular,

suffered in the double set-back from the

general alignment of the south buildings (right)

of the Plan. That the draftsman did not make this

revision quite fit is illustrated by the south and

west boundary fence lines intersecting just

outside of the confining edge of the parchment

(sheet 5).

Conditions here support a belief that the draftsman

was striving to overcome the constrictive

inadequacy of the parchment and that the

angular deviation from square, seen here, in part

at least, is evidence of an attempt to compensate

for inadequate space on which to trace directly

from the original parchment. Thus, the lack of

necessary space invited a degree of irregularity

in tracing that was not inadvertent—a compelling

argument, it seems, that the existing

Plan is a copy.

In other words, to achieve his objective—

fitting an image into a space too small—by

composing all the elements of the original within

the space at his disposal without drastically

changing the size of the buildings not appreciably

altering the scale of the Plan, the draftsman

began making incremental adjustments as

be traced, starting at a point somewhat removed

from the trouble spot at the southwest corner of

the parchment.

His estimate of small incremental adjustments of

contraction and deflection, as he proceeded with

the task, was remarkably successful. Apparent

distortion, and lack of symmetric perfection at

this location are really no less than a brilliant

solution to an impossible task.

E.B.

of boredom, exhaustion, declining interest in the act of

drafting, are not in evidence. On the contrary, the crisp,

neat execution prevailing elsewhere in the Plan persists here.

Ennui and enervation of draftsman do not seem to explain

this problem.[206]

In tracing the buildings the draftsman had to struggle

with the relative opaqueness of the sheet upon which he

traced his copy, or perhaps even with the difficult problem

of holding his sheets in a position that would allow the

reflected sunlight to penetrate the superimposed parchments

with sufficient strength to make the design of the

original readable through the body of the overlay. By

contrast the explanatory titles could be inscribed under

optimal conditions for the writing hand, as the parchment,

with its tracing completed, rested on the hard surface of a

table where the arm found solid support. The calligraphic

precision and firmness of the script leaves no doubt on this

score.

Since some of the inscriptions of sheet-group 1, 2, 3

continue under the overlapping margins of sheets 4 and 5,

been shown, must have been completed before sheets 4

and 5 were added. It is logical to presume that the inscriptions

of the two outer sheets (4 and 5) likewise were

entered before these sheets were attached to the center

group, since they would be easier to handle separately than

after attachment. In general (but by no means exclusively

so) the scribe's working procedure paralleled that of the

draftsman. The majority of the titles of the Church were

inscribed transversely, the scribe facing the Church from

the west, the position in which the parchments were held

as this building was traced. He rotated the skin counterclockwise

by 90 degrees before inscribing the long axial

title defining the length of the Church, plus the two other

longitudinal titles that list the span of the columnar interstices

of the nave arcades. Still facing the Church from the

north, he inscribed the titles of the Scriptorium and the

Library as well as those of all the lodgings that range along

the northern aisle of the Church (Visiting Monks, Master

of Outer School, and Porter). The titles of the corresponding

rooms on the southern side of the Church were entered

from the opposite direction, which required a counterrotation

of the parchment by 180 degrees. Further rotations

were necessitated by the inscriptions of the semicircular

titles of the two atria as well as the two circular

towers. Again the principle of rotation was used in placing

the inscriptions of the Cloister Yard and the buildings

around it. Here the scribe stationed himself conceptually

in the center of the cloister garth and entered his inscriptions

clockwise, rotating the parchment counterclockwise

beneath his hand as he moved from building to building

around the four corners of the square, until he had made

a complete turn of 360 degrees. Other cases involving

complete rotation are the circular enclosures for the

chicken and geese and the title hic mansiunculae scolasticarum

in the Outer School.

For the rest, i.e., all of the buildings ranging peripherally

around the Church and the claustral block, the scribe

followed the simple procedure of inscribing his titles

facing each respective tract from the outer edge of the

Plan, which relieved him of the need to bend far over the

parchment. Exceptions to this rule are made only in those

cases where the particular shape of a room forced the scribe

to enter his titles at right angles rather than parallel to the

edge of the Plan (typical cases: Abbot's House, and House

of the Fowlkeepers).

There are, however, two notable exceptions: the title

that defines the functions of the large cross in the Monks'

Cemetery, and the letter of transmittal entered on the

margin to the east of the cemetery. They face west, like the

majority of the titles of the Church, thus suggesting that

the Plan was to be primarily viewed from the west. An

inscription that does not fall into the normal pattern is the

title designating the entrance to the Library, perhaps an

afterthought. It straddles the north wall of the fore choir

and faces east, in contrast to all other titles written transversely

into the church.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||