The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I. 3. |

| I. 4. |

| I. 5. |

| I. 6. |

| I. 7. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I. 10. |

| I. 11. |

| I. 12. |

| I. 13. |

| I. 14. |

| I. 15. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

III.1.11

PARLOR

ITS DUAL ROLE: CONVERSATION WITH

VISITORS & WASHING OF FEET

Between the Cellar and the southern aisle of the church lies

the Parlor, a long rectangular room that serves as exit and entrance

to the Cloister, where the monks may engage in conversation

with their guests, and where the washing of the

feet takes place (exitus & introitus ante claustrū ad conloquendum

cum hospitibus & ad mandatū faciendū). The parlor measures

15 feet × 47½ feet and is lined entirely with benches. It

is the only legitimate place of contact between the monks and

the outside world. It is here that, with the permission of the

abbot or prior, they may meet with friends or visiting

relatives. Here, also, they perform one of the most venerable

Christian services, the so-called mandatum. Keller[254]

translated

the phrase ad mandatū faciendū mistakenly as "the

place where orders are given to the servants," and some of

the later commentators of the Plan inherited this error.[255]

Mandatum is "the washing of the feet" and refers to an old

monastic custom, based upon the example set by Christ

himself, when before the Last Supper he humbly washed

the feet of his disciples, admonishing them to fulfill his

"new mandate" (novum mandatum)[256]

by perpetuating this

rite. The custom has a long Biblical tradition and was widespread

in eastern countries, where owing to the general use

of sandals, the washing of the feet was from the earliest

times recognized everywhere as a courtesy shown to

guests. In the hot climate of the Mediterranean countries,

with their dusty and often rain-soaked roads, to offer water

to a guest for his feet was one of the duties of the master of

the household, and in certain areas was even the equivalent

of a formal invitation to stay overnight.[257]

Often this

service was rendered by slaves, occasionally by the daughter

or wife of the owner of the house.[258]

Common both in the

Jewish and the Hellenistic world, the custom of washing

feet was taken over by the Early Christian and became an

integral part of the monastic tradition.

Willis, 1848; Leclercq (in Cabrol-Leclercq, vi:1, 1924, col. 100)

did not correct this error. It lingers on in Reinhardt (1952, 12), but was

corrected in the same year by Alfred Häberle (Häberle, 1952).

John, 13:14-15: "If I then, your Lord and Master, have washed

your feet; ye also ought to wash one another's feet. For I have given you

an example, that you should do as I have done to you."

For full documentation on the history of the mandatum, see Schäfer,

1956; for summary reviews: Thalhofer's article "Fusswaschung," in

Kirchenlexikon, IV, 1882, cols. 2145-48; Thurston's article "Washing

of Feet and Hands," in the Catholic Encyclopedia, XV, 1912, 557-58;

as well as a most informative paragraph in Semmler, 1963, 37-39.

For references to sources for the occurrence of this rite in the

Jewish and Hellenistic world, see Schäfer, 1956, 20 and 59.

MANDATUM FRATRUM

AND

MANDATUM HOSPITUM

A distinction must be made between the mandatum

fratrum, i.e., the washing of the feet of one brother by

another, and the mandatum hospitum, the washing of the

feet of guests. St. Benedict establishes both rites as obligatory,

250. PLAN OF ST. GALL. AIR VIEW OF NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

This drawing is after the reconstruction model of the buildings of the Plan made for the exhibition Karl der Grosse, in Aachen, 1965.

Besides the Monastery Church (an airview of which is shown in fig. 352) the building complex which accommodates the claustral compounds

of the Novitiate and Infirmary, in consummate symmetry on either side of the dominant mass of a double apsed Church, is the largest single

building shown in the Plan. Its layout, wholly unrelated to the vernacular tradition of the North, is one of the finest products of the Carolingian

renascence—a concept perhaps inspired by the layout of the Constantinian aula at Trier (fig. 240) or Roman imperial summer residences,

such as Konz (fig. 241) and Kloosterberg (fig. 242). Its classicism could be defined as an architectural counterpart to some of the finest and

most classicising manuscripts of the so-called Palace School, such as the famous Aachen or Vienna treasure Gospels, whose evangelists,

portrayed in senatorial robes and seated in open landscapes, cannot be stylistically derived from the preceding Hiberno-Saxon schools of

illumination, but are a revival of an illusionistic Roman tradition that had been lost in the shuffle of the Great Migrations.

hospitum, as it is in the service rendered to the poor "that

Christ is most truly welcomed."[259] The so-called Customs

of Farfa (in reality the Customs of Cluny, written under

Abbot Odilo, between 1030 and 1048) furnish us with a

complete description of this ritual.[260] The brother who is

placed in charge of the service saw that everything indispensable

for its conduct was kept in readiness: "the

cauldron, in which the water is heated" (laebetem ubi

aquam calefaciat), "the basin in which their feet are washed"

(concam ad lavandum pedes eorum) and "three towels of

linen" (tria linteamenta). One towel was used for drying

the hands of the monks in charge of the service; with the

second the pauper's feet were dried; the third one was for

drying their hands.[261] The ritual took place after the

evening meal, when the brothers left the refectory, assembled

in procession in the cloister wing "next to the cellar"

(juxta promptuarium)[262] and chanted the songs by which

the service was introduced. The feet of one pauper after

another were washed, and the monks to whom this task

was assigned alternated with one another, each in succession.

The first monk washed, dried, and kissed the feet of

the first pauper. The second one relieved him of the towel

and basin and carried it to the brother who stood near the

water and the aqua manile, dried his own hands and withdrew

to his station. Then the next brother advanced to

attend to the next pauper, and the procedure was repeated

until the feet of all were washed. At the end the pauper's

hands were rinsed.[263]

While the feet of the newly arrived guests were washed

daily, the mandatum fratrum was a weekly service extended

to the assembled brothers by the incoming and outgoing

servers, each Saturday after the evening meal. Although it

is quite clear that the feet of the paupers were washed in

the Parlour—both in the light of the latter's explanatory

title, as well as in view of the fact that the Parlour was the

only place where monks could legitimately meet with

guests—the Plan of St. Gall does not tell us anything

about the place where the feet of the brothers were

washed. In leading Benedictine monasteries of the eleventh

century it was done in the chapter house, as can be deduced

without any shadow of doubt from the Customs of Farfa

(1030-48), the Customs of the Monastery of Bec, composed

on the request of Lanfranc while he was prior of his

abbey, 1045-70 and the Customs of Lanfranc, worked out

by Lanfranc between 1070 and 1077 for Christchurch

Monastery after he had been made archbishop of Canterbury.[264]

The monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall, as has

been pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, was not

provided with a separate chapter house. The chapter

meetings were held in the cloister wing that ran along the

southern aisle of the Church, and for that purpose the wing

was furnished with two benches extending its entire length.

This was the only place in the cloister beside the Refectory

where the monks could be seated en masse, as they would

have to be when their feet were washed. It is for this

reason, as well as the association of the rite with the

chapter house in later centuries, that I am inclined to

assume that in the monastery portrayed on the Plan, the

mandatum fratrum was performed in the northern cloister

wing. During inclement weather both the chapter meetings

and the mandatum fratrum may have been shifted to the

Warming Room.[265]

The rite of the washing of feet was dear to the brothers.

When the abbot of Fulda proposed to abolish it, the monks

of that monastery remonstrated before the emperor who

ordered it to be reinstated.[266]

In remembrance of the

washing of the feet of the disciples of Christ before the

Last Supper, the mandatum conducted on Maundy

Thursday was a special event. The synod of 816 directs

that on this day the service be rendered by the abbot

himself, who dries the feet of each monk with his own

hands and serves him a drink in a beaker.[267]

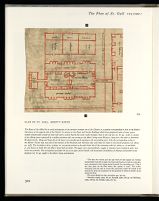

251. PLAN OF ST. GALL. ABBOT'S HOUSE

The House of the Abbot lies in axial prolongation of the northern transept arm of the Church, in a position corresponding to that of the Monk's

Dormitory on the opposite side of the Church. In contrast to the Guest and Service Buildings which have peripheral suites of outer spaces

ranged symmetrically around an inner hall with a central hearth that emits smoke through a hole in the roof (see vol. II, pp. 117ff), it consists

of two oblong spaces separated by a median partition wall, one serving as the abbot's living room (Mansio Abbatis), the other as dormitory

(Dormitoriū). Along each long side of the house is an arcaded porch opening on the surrounding yard. Like the corresponding arches in

the Monks' Cloister (fig. 203) and in the cloisters of the Novitiate and Infirmary (fig. 236) these are shown in horizontal projection (cf. above,

pp. 55ff). The inscription SUPRA CAMERA ET SOLARIUM written in the pale brown ink of the correcting scribe (cf. above, p. 13 and below

p. 321) leaves no doubt that the abbot's house had two levels. The upper story accommodated a supply or treasure room (CAMERA) and a sun

room (SOLARIUM). This arrangement precludes the use of an open central hearth, and necessitates installation of chimney-surmounted corner

fireplaces (cf. II, pp. 249ff) in the abbot's living and bedroom.

Benedicti regula, chap. 35 (mandatum fratrum), and chap. 53

(mandatum hospitum); ed. Hanslik, 1960, 93 and 124; ed. McCann,

1952, 88-89 and 120-21; ed. Steidle, 1952, 227 and 258.

Consuetudines Farfenses, book I, chap. 54 and book II, chap. 46;

ed. Albers, Cons. mon., I, 1900, 49-50 and 178-79.

"Postea dicantur aliae antiphonae, donec singuli fratres singulis

pauperibus pedes lavent, tergant et osculentur. Ille namque qui lavat, tergat

atque osculetur eorum pedes; alius accipiens linteum inprimis comcam: ipse

eat locum ubi frater stat cum aqua et manule, abluat manus suas et regrediatur

in suum locum. Caeteri similiter faciant; dum omnes abluti fuerint,

incipiant donare aqua illorum manibus, tenente fratre mutuo manule ad

illos . . . Ibid., loc. cit.

This fact is not sufficiently stressed in the literature on the mandatum

fratrum. The Customs of Lanfranc deal with the ritual in chapter

35 (DE MANDATO FRATRUM) where it is stated with unequivocal

clarity that "the brothers after having left the refectory . . . and having

congregated in the chapter house (egressis fratribus . . . Introgressis in

capitulum fratribus) were joined there by the abbot and the prior (abbas

et prior . . . ueniant in capitulum) "followed by those brothers to whom

this task had been assigned that same day in the chapter meeting and

who each in turn with bent knees wash the brothers feet, dry them and

kiss them" (sequentibus eos fratribus, qui ad seruitium eorum ipsa die in

capitulo fuerant ordinati, et utrique flexis genibus lauent pedes fratrum et

tergant et osculentur). Decreta Lanfranci chap. 35, ed. Knowles, in Corp.

cons. mon. III, 1967, 32.

The Customs of Le Bec are equally clear on this matter: "After the

evening meal . . . the prior rings the bell . . . and all assemble in the

chapter house . . . Then the abbot and the prior enter the chapter house

. . . and wash, dry and kiss the feet of everyone" (post prandium . . .

sonet prior tabulam . . . et omnes conveniant in capitulum . . . Tunc abbas

et prior . . . ingrediantur capitulum . . . pedes omnium lavent, tergant et

osculetur). Consuetudines Beccenses, chap. 87; ed. Dickson, Corp. cons.

mon., IV, 1967, 46.

The Customs of Farfa are not quite that clear. The location of the rite,

however, is indicated in the decisive phrase in book I, chap. 54, which

informs us that at the end of the washing of the brother's feet and deacon

and three of the servers go to the church to don liturgical robes, then

return to the chapter house, where, upon their entry, all of the assembled

brothers stand (Quibus ita capitulum intrantibus ante Evangelium surgant

omnes). Consuetudines Farfenses, book I, chap. 54; ed. Albers, Cons.

mon., I, 1900, 50.

For further reference to sources attesting that the mandatum fratrum

was held in the chapter house, see Schäfer, 1956, 64, note 22; and 66.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||