I.14.6

SUCCESSIVE STAGES IN THE

CONCEPTUAL GROWTH OF THE

LAYOUT OF CHURCH AND CLAUSTRUM

If the observations on the modular basis of the Plan

presented in the preceding paragraphs of this chapter are

correct, the procedure followed in the construction of the

layout of the Church and the Claustrum can be reconstructed

as follows:

Step 1 (fig. 67):

The draftsman first constructed the grid of 40-foot squares

which determined the overall dimensions of the Church.

This grid established the boundaries of the nave, the

transept, and the choir, as well as those of the two subsidiary

contiguous spaces of the Sacristy and the Scriptorium.

The transept was composed of three, the nave of

four and one-half 40-foot squares. The introduction of an

extra half-square in the nave was inevitable, if the draftsman

started from the premise that his church should be

300 feet long. The columns of the nave arcades were

plotted at a distance of 20 feet, so that each second column

came to coincide with one of the corners of its corresponding

40-foot square. The width of the aisles, at that

stage, was meant to be half the width of the nave, i.e., 20

feet.

Step 2 (fig. 68):

In working on the internal layout of the Church, the draftsman

was aware that an acute shortage of space would occur

in actual construction if no allowance was made for the

thickness of the aisle walls where the Church was abutted

by other masonry structures. He took account of this

contingency by moving the center line of his aisle walls 2½

feet further out and producing the safety strip previously

mentioned. Within the schematic floor space of the church

created in this manner, he could now map out the foundations

for his columns and altars by a system of auxiliary

construction lines which divided the Church lengthwise in

the sequence

5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15 · 5 · 15

and crosswise in the sequence

5 · 5 · 7½ · 5 · 5 · 12½ · 10 · 12½ · 5 · 5 · 7½ · 5 · 5

The altar screens in the aisles are inscribed into 7½-foot

squares, the altars in the nave, the ambo, and the baptismal

font into 10-foot squares. The system of auxiliary construction

lines shown in figure 68 is the minimum required

for the internal layout of the Church.

Had the wall thickness been inked in as solid bars, the

Church would have appeared as shown in figure 56. This

is the manner in which it was interpreted by Graf, Ostendorf,

and Gall, and it is interesting to note that this concept

can be translated into the language of a modern architectural

drawing without sustaining the slightest distortion. Had the

designer of the Church intended to draw the Plan in this

manner, it would have been fully within the scope of his

capabilities. If he confined himself to the more abstract

procedure of simple linear definition, it probably was

because he had the task of designing the layout of not just a

church, but an entire monastery comprised of a multitude

of buildings of greatly varying dimensions, where the

drawing out of wall thicknesses would have introduced

unnecessary complications.

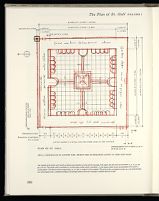

Step 3 (fig. 69):

After the floor plans of the Church were completed, the

draftsman could lay out the cloister yard with a relatively

simple system of auxiliary lines, inheriting from the

Church, of course, the five-foot displacement from the

superordinate grid of 40-foot squares which transmitted

itself to all of the contiguous structures (Dormitory,

Refectory, and Cellar). The cloister yard was designed to

cover a surface area 100 feet square, and as a strip 12½ feet

wide was taken off on either side for the covered walk (15

feet in the north), a surface area 75 feet square was left for

the open

pratellum in the center. Arches which open into

the latter from the center of each covered walk are 10 feet

wide and 7½ feet high, while the galleried openings on

either side measure 5 × 5 feet, leaving in the corners a

solid piece of masonry 7½ feet long. The square in the

center of the

pratellum measures 20 feet on each side.