The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress being some account of the steamship Quaker City's pleasure excursion to Europe and the Holy land ; with descriptions of countries, nations, incidents and adventures, as they appeared to the author |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. | CHAPTER XVIII. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||

18. CHAPTER XVIII.

ALL day long we sped through a mountainous country

whose peaks were bright with sunshine, whose hillsides

were dotted with pretty villas sitting in the midst of gardens

and shrubbery, and whose deep ravines were cool and shady,

and looked ever so inviting from where we and the birds were

winging our flight through the sultry upper air.

We had plenty of chilly tunnels wherein to check our perspiration,

though. We timed one of them. We were twenty

minutes passing through it, going at the rate of thirty to

thirty-five miles an hour.

Beyond Alessandria we passed the battle-field of Marengo.

Toward dusk we drew near Milan, and caught glimpses of

the city and the blue mountain peaks beyond. But we were

not caring for these things—they did not interest us in the

least. We were in a fever of impatience; we were dying to

see the renowned Cathedral! We watched—in this direction

and that—all around—every where. We needed no one to

point it out—we did not wish any one to point it out—we

would recognize it, even in the desert of the great Sahara.

At last, a forest of graceful needles, shimmering in the

amber sunlight, rose slowly above the pigmy house-tops, as

one sometimes sees, in the far horizon, a gilded and pinnacled

mass of cloud lift itself above the waste of waves, at sea,—the

Cathedral! We knew it in a moment.

Half of that night, and all of the next day, this architectural

autocrat was our sole object of interest.

What a wonder it is! So grand, so solemn, so vast! And

weight, and yet it seems in the soft moonlight only a fairy

delusion of frost-work that might vanish with a breath! How

sharply its pinnacled angles and its wilderness of spires were

cut against the sky, and how richly their shadows fell upon its

snowy roof! It was a vision!—a miracle!—an anthem sung

in stone, a poem wrought in marble!

Howsoever you look at the great Cathedral, it is noble, it is

beautiful! Wherever you stand in Milan, or within seven

miles of Milan, it is visible—and when it is visible, no other

object can chain your whole attention. Leave your eyes

unfettered by your will but a single instant and they will

surely turn to seek it. It is the first thing you look for when

you rise in the morning, and the last your lingering gaze rests

upon at night. Surely, it must be the princeliest creation that

ever brain of man conceived.

At nine o'clock in the morning we went and stood before

this marble colossus. The central one of its five great doors is

bordered with a bas-relief of birds and fruits and beasts and

insects, which have been so ingeniously carved out of the

marble that they seem like living creatures—and the figures

are so numerous and the design so complex, that one might

study it a week without exhausting its interest. On the great

steeple—surmounting the myriad of spires—inside of the spires

—over the doors, the windows—in nooks and corners—every

where that a niche or a perch can be found about the enormous

building, from summit to base, there is a marble statue,

and every statue is a study in itself! Raphael, Angelo,

Canova—giants like these gave birth to the designs, and their

own pupils carved them. Every face is eloquent with expression,

and every attitude is full of grace. Away above, on the

lofty roof, rank on rank of carved and fretted spires spring

high in the air, and through their rich tracery one sees the sky

beyond. In their midst the central steeple towers proudly up

like the mainmast of some great Indiaman among a fleet of

coasters.

We wished to go aloft. The sacristan showed us a marble

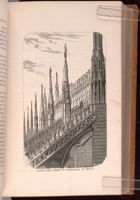

ROOFS AND SPIRES OF CATHEDRAL AT MILAN.

[Description: 500EAF. Illustration page. Image of the spires of churches in Milan, all topped with statues of people.]

—there is no other stone, no brick, no wood, among its building

materials,) and told us to go up one hundred and eighty-two

steps and stop till he came. It was not necessary to say

stop—we should have done that any how. We were tired by

the time we got there. This was the roof. Here, springing

from its broad marble flagstones, were the long files of spires,

looking very tall close at hand, but diminishing in the distance

like the pipes of an organ. We could see, now, that

the statue on the top of each was the size of a large man,

though they all looked like dolls from the street. We could

hollow spires, from sixteen to thirty-one beautiful marble

statues looked out upon the world below.

From the eaves to the comb of the roof stretched in endless

succession great curved marble beams, like the fore-and-aft

braces of a steamboat, and along each beam from end to end

stood up a row of richly carved flowers and fruits—each separate

and distinct in kind, and over 15,000 species represented.

At a little distance these rows seem to close together like the

ties of a railroad track, and then the mingling together of the

buds and blossoms of this marble garden forms a picture that

is very charming to the eye.

We descended and entered. Within the church, long rows

of fluted columns, like huge monuments, divided the building

soft blush from the painted windows above. I knew the

church was very large, but I could not fully appreciate its

great size until I noticed that the men standing far down by

the altar looked like boys, and seemed to glide, rather than

walk. We loitered about gazing aloft at the monster windows

all aglow with brilliantly colored scenes in the lives of the

Saviour and his followers. Some of these pictures are mosaics,

and so artistically are their thousand particles of tinted glass

or stone put together that the work has all the smoothness

and finish of a painting. We counted sixty panes of glass in

one window, and each pane was adorned with one of these

master achievements of genius and patience.

The guide showed us a coffee-colored piece of sculpture

which he said was considered to have come from the hand of

Phidias, since it was not possible that any other artist, of any

epoch, could have copied nature with such faultless accuracy.

The figure was that of a man without a skin; with every vein,

artery, muscle, every fibre and tendon and tissue of the human

frame, represented in minute detail. It looked natural, because

somehow it looked as if it were in pain. A skinned man

would be likely to look that way, unless his attention were

occupied with some other matter. It was a hideous thing, and

yet there was a fascination about it some where. I am very

sorry I saw it, because I shall always see it, now. I shall

dream of it, sometimes. I shall dream that it is resting its

corded arms on the bed's head and looking down on me with

its dead eyes; I shall dream that it is stretched between the

sheets with me and touching me with its exposed muscles and

its stringy cold legs.

It is hard to forget repulsive things. I remember yet how

I ran off from school once, when I was a boy, and then, pretty

late at night, concluded to climb into the window of my

father's office and sleep on a lounge, because I had a delicacy

about going home and getting thrashed. As I lay on the

lounge and my eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, I

fancied I could see a long, dusky, shapeless thing stretched

my face to the wall. That did not answer. I was afraid that

that thing would creep over and seize me in the dark. I

turned back and stared at it for minutes and minutes—they

seemed hours. It appeared to me that the lagging moonlight

never, never would get to it. I turned to the wall and

counted twenty, to pass the feverish time away. I looked—

the pale square was nearer. I turned again and counted fifty

—it was almost touching it. With desperate will I turned

again and counted one hundred, and faced about, all in a

tremble. A white human hand lay in the moonlight! Such

an awful sinking at the heart—such a sudden gasp for breath!

I felt—I can not tell what I felt. When I recovered strength

enough, I faced the wall again. But no boy could have

remained so, with that mysterious hand behind him. I

counted again, and looked—the most of a naked arm was

could stand it no longer, and then—the pallid face of a man

was there, with the corners of the mouth drawn down, and

the eyes fixed and glassy in death! I raised to a sitting posture

and glowered on that corpse till the light crept down the

bare breast,—line by line—inch by inch—past the nipple,—

and then it disclosed a ghastly stab!

I went away from there. I do not say that I went away in

any sort of a hurry, but I simply went—that is sufficient. I

went out at the window, and I carried the sash along with me.

I did not need the sash, but it was handier to take it than it

was to leave it, and so I took it.—I was not scared, but I was

considerably agitated.

When I reached home, they whipped me, but I enjoyed it.

It seemed perfectly delightful. That man had been stabbed

near the office that afternoon, and they carried him in there to

doctor him, but he only lived an hour. I have slept in the

same room with him often, since then—in my dreams.

Now we will descend into the crypt, under the grand altar

of Milan Cathedral, and receive an impressive sermon from

lips that have been silent and hands that have been gestureless

for three hundred years.

The priest stopped in a small dungeon and held up his

candle. This was the last resting-place of a good man, a

warm-hearted, unselfish man; a man whose whole life was

given to succoring the poor, encouraging the faint-hearted,

visiting the sick; in relieving distress, whenever and wherever

he found it. His heart, his hand and his purse were always

open. With his story in one's mind he can almost see his

benignant countenance moving calmly among the haggard

faces of Milan in the days when the plague swept the city,

brave where all others were cowards, full of compassion where

pity had been crushed out of all other breasts by the instinct

of self-preservation gone mad with terror, cheering all, praying

with all, helping all, with hand and brain and purse, at a

time when parents forsook their children, the friend deserted

her pleadings were still wailing in his ears.

This was good St. Charles Borroméo, Bishop of Milan. The

people idolized him; princes lavished uncounted treasures

upon him. We stood in his tomb. Near by was the sarcophagus,

lighted by the dripping candles. The walls were faced

with bas-reliefs representing scenes in his life done in massive

silver. The priest put on a short white lace garment over his

black robe, crossed himself, bowed reverently, and began to

turn a windlass slowly. The sarcophagus separated in two

parts, lengthwise, and the lower part sank down and disclosed

a coffin of rock crystal as clear as the atmosphere. Within lay

the body, robed in costly habiliments covered with gold embroidery

and starred with scintillating gems. The decaying

head was black with age, the dry skin was drawn tight to the

bones, the eyes were gone, there was a hole in the temple and

another in the cheek, and the skinny lips were parted as in a

ghastly smile! Over this dreadful face, its dust and decay,

and its mocking grin, hung a crown sown thick with flashing

brilliants; and upon the breast lay crosses and croziers of

solid gold that were splendid with emeralds and diamonds.

How poor, and cheap, and trivial these gew-gaws seemed in

presence of the solemnity, the grandeur, the awful majesty of

Death! Think of Milton, Shakspeare, Washington, standing

before a reverent world tricked out in the glass beads, the

brass ear-rings and tin trumpery of the savages of the plains!

Dead Bartoloméo preached his pregnant sermon, and its

burden was: You that worship the vanities of earth—you that

long for worldly honor, worldly wealth, worldly fame—behold

their worth!

To us it seemed that so good a man, so kind a heart, so

simple a nature, deserved rest and peace in a grave sacred

from the intrusion of prying eyes, and believed that he himself

would have preferred to have it so, but peradventure our

wisdom was at fault in this regard.

As we came out upon the floor of the church again, another

priest volunteered to show us the treasures of the church.

we had just visited, weighed six millions of francs in ounces

and carats alone, without a penny thrown into the account for

the costly workmanship bestowed upon them! But we followed

into a large room filled with tall wooden presses like

wardrobes. He threw them, open, and behold, the cargoes of

“crude bullion” of the assay offices of Nevada faded out of

my memory. There were Virgins and bishops there, above

their natural size, made of solid silver, each worth, by weight,

from eight hundred thousand to two millions of francs, and

bearing gemmed books in their hands worth eighty thousand;

there were bas-reliefs that weighed six hundred pounds, carved

in solid silver; croziers and crosses, and candlesticks six and

eight feet high, all of virgin gold, and brilliant with precious

stones; and beside these were all manner of cups and vases,

and such things, rich in proportion. It was an Aladdin's

workmanship, were valued at fifty millions of francs! If

I could get the custody of them for a while, I fear me the market

price of silver bishops would advance shortly, on account

of their exceeding scarcity in the Cathedral of Milan.

The priests showed us two of St. Paul's fingers, and one of

St. Peter's; a bone of Judas Iscariot, (it was black,) and also

bones of all the other disciples; a handkerchief in which the

Saviour had left the impression of his face. Among the most

precious of the relics were a stone from the Holy Sepulchre,

part of the crown of thorns, (they have a whole one at Notre

Dame,) a fragment of the purple robe worn by the Saviour, a

nail from the Cross, and a picture of the Virgin and Child

painted by the veritable hand of St. Luke. This is the second

of St. Luke's Virgins we have seen. Once a year all these

holy relics are carried in procession through the streets of

Milan.

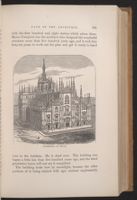

I like to revel in the dryest details of the great cathedral.

The building is five hundred feet long by one hundred and

eighty wide, and the principal steeple is in the neighborhood

of four hundred feet high. It has 7,148 marble statnes, and

will have upwards of three thousand more when it is finished.

In addition, it has one thousand five hundred bas-reliefs. It

has one hundred and thirty-six spires—twenty-one more are to

be added. Each spire is surmounted by a statue six and a

half feet high. Every thing about the church is marble, and

all from the same quarry; it was bequeathed to the Archbishopric

for this purpose centuries ago. So nothing but the

mere workmanship costs; still that is expensive—the bill foots

up six hundred and eighty-four millions of frances, thus far

(considerably over a hundred millions of dollars,) and it is

estimated that it will take a hundred and twenty years yet

to finish the cathedral. It looks complete, but is far from

being so. We saw a new statue put in its niche yesterday,

alongside of one which had been standing these four hundred

years, they said. There are four staircases leading up to the

main steeple, each of which cost a hundred thousand dollars,

Marco Compioni was the architect who designed the wonderful

structure more than five hundred years ago, and it took him

forty-six years to work out the plan and get it ready to hand

over to the builders. He is dead now. The building was

begun a little less than five hundred years ago, and the third

generation hence will not see it completed.

The building looks best by moonlight, because the older

portions of it being stained with age, contrast unpleasantly

broad for its height, but may be familiarity with it might dissipate

this impression.

They say that the Cathedral of Milan is second only to St.

Peter's at Rome. I can not understand how it can be second

to any thing made by human hands.

We bid it good-bye, now—possibly for all time. How surely,

in some future day, when the memory of it shall have lost its

vividness, shall we half believe we have seen it in a wonderful

dream, but never with waking eyes!

| CHAPTER XVIII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||