The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

THE MEASURE OF WINE AND BEER ALLOWED TO

THE MONKS |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

THE MEASURE OF WINE AND BEER ALLOWED TO

THE MONKS

Conflicting views among the early fathers

Most of the early desert monks looked upon wine as an

unsuitable drink; St. Anthony never touched it and even

St. Pachomius struck it entirely from the diet of his monks

except in case of sickness.[222]

But others, such as Palladius

(d. 431) proclaimed that "it is better to drink wine with

measure than water with hubris."[223]

The moderates among

the early fathers had a powerful precedent to lean upon

since the Lord himself drank wine (Matt. IX, 11). St.

Benedict settled the controversy with his distinctive discretion.

"We do indeed read that wine is no drink for

monks; but since nowadays monks cannot be persuaded of

this, let us at least agree upon this, to drink temperately

and not to satiety."[224]

Vinum et liquamen absque loco aegrotantium nullus attingat ("Outside

the infirmary no one shall touch wine and oil"), Rule of St. Pachomius,

chap. 45, ed. Boon, 1932, 24. Even when on leave of absence from the

monastery while visiting a diseased relative, this rule was rigidly enforced;

see chap. 54 of the Rule, ed. Boon, 30.

I am taking these data from Steidle's commentary to chap. 40 of

the Rule of St. Benedict; Steidle, 1952, 238. For other early proponents

of moderate use of wine see Delatte, 1913, 315.

Licet legamus uinum omnino monachorum non esse, sed quia nostris

temporibus id monachis persuaderi non potest, saltim uel hoc consentiamus,

ut non usque ad sacietatem bibamus, sed parcius; Benedicti regula, chap. 40,

ed. Hanslik, 1960, 101-102; ed. McCann, 1952, 96-99; ed. Steidle, 1952,

237-38. The source referred to by St. Benedict is the Verba Seniorum.

Cf. Delatte, 1913, 314, note 1.

No difference in alcoholic content between ancient

and modern wines

Concerning the concentration of alcohol in wine, there

is no reason to presume any appreciable difference between

wines of ancient and modern times. Table wines (wine consumed

with meals) cannot have less than 8 per cent alcohol

by volume (at lower levels, the wine will not be stable, and

will tend to spoil), and in general no more than 12 per cent.

(At levels of alcohol higher than this, the wines are no

longer table wines but are classified as sweet wines, the

production of which requires special treatment or fortification

by artificial sugars.)[225]

The concentration of alcohol in wine is conditioned by the volume

of sugar occurring in the grapes from which the wine is made. My

colleagues, M. A. Amerine and William B. Fretter, inform me that the

sugar content of Central European grapes varies roughly between 16

per cent and an upper limit of 24 per cent, yielding a lower limit of 8 per

cent and an upper limit of 12 per cent alcohol in the wine. If the sugar

content falls below or rises above these limits, the yeast cells which

convert the sugar into alcohol will either not be capable of starting

fermentation or will cease to perform that function through attrition in

too high a volume of alcohol. For more detail on the technology of wine-making,

see Amerine and Joslyn, 1970 (2nd. ed.), especially chaps. 7, 8,

9, and 10.

The hemina of St. Benedict: Charlemagne's

attempts to establish its value

St. Benedict allows each monk "a hemina of wine a

day"[226]

and leaves it to the discretion of the prior to add

to this a little more "if the circumstances of the place, or

their work, or the heat of the summer require more."[227]

He holds out the promise of a "special reward" for those

"upon whom God bestows abstinence"[228]

and admonishes

the superior "to take care that neither surfeit nor drunkeness

supervene."[229]

The precise content of the measure of

wine which St. Benedict designated with the term hemina

is unknown.[230]

Charlemagne made an attempt to ascertain

243. GERASA (JERASH), PALESTINE. THREE EARLY CHRISTIAN SANCTUARIES ON AXIS

[after Krautheimer, 1965, 119, fig. 50]

In the foreground and to the left the atrium and church of St. Theodore, built A.D. 494-496; in the center, but on a slightly lower level, the

cathedral of Gerasa, built around A.D. 400. It had at its rear another atrium enclosing a shrine of St. Mary located directly behind the apse of

the cathedral. This atrium was approached by a grand staircase from yet a lower level. Three sanctuaries were thus aligned on a common axis.

244. CANTERBURY, ENGLAND

PLAN OF SAXON ABBEY CHURCH OF SS PETER AND PAUL, FOUNDED BY ST. AUGUSTINE (597-604), AND THE CHURCH OF ST. MARY

[same period; after Clapham, 1955]

To the left lies the church of SS Peter and Paul; to the right, the church of St. Mary. The church of St. Pancras, lying in eastern

prolongation of the axis of these two churches, and dating from the same period, is not visible in this plan. The church of St. Wulfric (interposed

between SS Peter and Paul and St. Mary) was not part of the original concept. In the medieval monastery of St. Gall, St. Peter's chapel

(prior to 830), Gozbert's church (830-836) and Otmar's church (dedicated 867) lay in axial prolongation; see II, figs. 507-509.

Hildemar, in discussing this event, in his commentary to

chapter 40 of the Rule of St. Benedict, claims that the

emperor succeeded in retrieving the old measure and that

this was the measure currently used in the monasteries of

the empire as the basis for the daily allotment of wine.[231]

The event is also referred to in a letter by Abbot Theodomar

of Monte Cassino to Charlemagne, where it is said

that a sample measure was dispatched to the emperor. Two

of these according to the estimate of the older brothers of

Monte Cassino formed the equivalent of the hemina of St.

Benedict, one being served at the midday meal, the other

at supper.[232] The text leaves no margin for doubt: it was

not the original hemina of St. Benedict (or a duplicate

thereof) that the emperor received from Monte Cassino

but a sample of which the senior monks "supposed"

(aestimaverunt, i.e., judged by careful consideration, yet

from incomplete data) that it was half the equivalent of that

measure. St. Benedict's original hemina, as we learn from

Paul the Deacon's History of the Lombards had been taken

to Rome by the Monks of Monte Cassino, as they fled from

the invading barbarians in 581, together with the original

measure for the Benedictine pound of bread, and the

original manuscript of the Rule of St. Benedict.[233] There

is no evidence that these two measures were returned to

the monastery in 720 when it was rebuilt, and the content

of Theodomar's letter, as well as a good deal of other

evidence, indicates clearly that in the eighth century even

in St. Benedict's own monastery the precise value of the

Benedictine hemina was forgotten.[234]

Tamen infirmorum contuentes inuecillitatem credimus eminam uini per

singulos sufficere per diem. Benedicti regula, loc. cit.

Quod si aut loci necessitas uel labor aut ardor aestatis amplius poposcerit,

in arbitrio prioris consistat. Benedicti regula, loc. cit. The reform

synod of 816 confirmed the directive of St. Benedict that a special

measure may be added to the regular pittance of wine on days on which

the monks were subject to heavy labor, and added to those the days

when they celebrated the mass for the dead. Synodi primae decr. auth.,

chap. 11; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 163, 373.

Quibus autem donat deus tolerantiam abstinentiae, propriam se

habituros mercedem sciant. Benedicti regula, loc. cit.

Endless discussions have been carried on with regard to this subject,

ever since Claude Lancelot, in 1667 published his Dissertation sur

l'hemine et la livre de pain de Saint Benoit et d'autres anciens religieux.

(For this and other early literature on the subject see Delatte, 1913, 309

and 313ff.) The issue may never be solved to full satisfaction, but it has

fascinating cultural implications; and the question just how seriously

the design, the dimensions and the number of the barrels in the Monks'

Cellar must be taken, cannot be settled without establishing, at least in a

tentative form the upper and lower limits of the daily ration of wine that

each monk was permitted to drink with his meal at the time of Louis the

Pious, the reason we attach some importance to this subject.

Unde Carolus rex, qualiter ipsam heminam intellegere ac scire potuisset,

misit Beneventum ad ipsam monasterium S. Benedicti, et ibi reperit antiquam

heminam, et juxta illam heminam datur monachis vinum. Similiter

et juxtam eam habemus etiam et nos. Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller,

1880, 445.

Misimus etiam mensuram potus, quae prandio, et aliam, quae cenae

tempore debeat fratribus praeberi; quas duas mensuras aestimauerunt

maiores nostri emine mensuram esse. Direximus etiam et mensuram unius

calicis, quam obsequiaturi fratres iuxta sacrae regulae textum solent accipere.

Theodomari epistola ad Karolum regem, chap. 4; ed. Hallinger and

Wegener, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 163. There is some question about

the authenticity of this letter. See Hallinger and Wegener, loc. cit.;

Semmler, 1963, 53-54; and Winandy, 1938.

Pauli Historia Langobardorum, Book IV, chap. 17; ed. Bethman

and Waitz, Mon. germ. hist., Sript. rer. Lang., Hannover 1878, 122:

Circa haec tempora coenobium beati Benedicti patris, quod in castro Casino

situm est, a Langobardis noctu invaditur. Qui universa diripientes, nec unum

de monachis tenere potuerunt, ut prophetia venerabilis Benedicti patris . . .

dixit . . . Fugientes quoque ex eodem loco monachi Roman petierunt secum

codicem sanctae regulae, quam praefatus pater composuerat, et quaedam

alia scripta necnon pondus panis et mensuram vini et quidquid ex supellecti

subripere poterant deferentes.

The Carolingian inflation of capacity measures

The leaders of the Church, under Charlemagne, and

even more so under Louis the Pious, had some reason to

be concerned with this issue, since in the lifetime of these

two rulers, the hemina had more than doubled its value.

The base of the Carolingian system of capacity measure,

as that of the Romans, was the modius internally divided

into 2 situlae, 16 sextarii, and 32 heminae. The classical

Roman modius had a capacity equivalent to 8.49 liters, the

hemina to 0.2736 liters.[235]

Between the fall of the Roman

Empire and its renovation under Charlemagne the capacity

use in the Frankish kingdom and in the early years of the

reign of Charlemagne was equivalent to 34.8 liters. In a

capitulary of 794, Charlemagne instituted a new modius,

larger by one third than the preceding one, which brought

the modius up to an equivalent of 52.2 liters. Before 822,

Louis the Pious increased again the newly established

modius of his father, this time by one fourth of its current

value, which brought it up to an equivalent of 68 liters.

Thus in the short span of not more than 25 years, the

hemina had risen from a capacity equivalent to 1.06 liters

(in use when Charlemagne acceded to his throne) to one

equivalent to 1.46 liters (instituted by Charlemagne in 794)

and finally to one equivalent to 2.12 liters (instituted by

Louis the Pious, prior to 822).[236] The inflation clearly

worked in favor of the monks, with proportions that must

have taxed the wit of even the most astute monastic leaders.

St. Benedict may have foreseen such possibilities when he

foreclosed all future abuse with the qualifying clause that

whatever measure of wine the abbot should be willing to

grant, "he always take care that neither surfeit nor drunkeness

supervene,"[237] a directive that as the centuries passed

by must have proved to be a more trustworthy guide than

any reliance on capriciously changing physical capacity

measures.

For the liter equivalents of the old Roman modius and hemina see

Pauly-Wissowa, Real Encyclopädie, s.v.

I am basing these calculations on the data assembled by M. G.

Guérard, who deals with Carolingian measures of capacity, on pp. 183ff

and 960ff of his admirable work on the Polyptique of Abbot Irminon

(Guérard, I, 1844. If Guérard's analysis of the relative values of the

measures here cited is wrong, my conclusions will be wrong. I have no

reason to doubt his findings.

The probable daily allowance of wine at the time

The Plan of St. Gall was drawn

The hemina that St. Benedict had in mind probably

came closer to that which was in use under the Romans in

classical times than to any of the later Frankish measures.

This would have entitled the monks to drink a little over a

fourth and perhaps as much as a third of a liter of wine

per day. Whether taken in the course of a single meal or

spaced out over two meals, this amount could hardly have

had any damaging effects on health or have lead to "surfeit"

or "drunkeness," especially not if these meals were

followed, as they traditionally were, by either a brief

period of rest,[238]

or by sleep.[239]

St. Benedict's assessment

of the quantity of wine that could be safely consumed at

the monks' table was both conservative and judicious. But

in evaluating his ruling historically one must not lose

sight of the fact that when St. Benedict took the epochal

step of sanctioning the consumption of wine for the

monastic community, the issue was as yet a highly controversial

one. Once the decision was made, the frailties of

human nature would tend to push the allowance upward.

From 0.2736 liters to 0.5 liters is not a big step; the less so,

if one considers the great inflation the hemina experienced

as an official capacity measure between the time of St.

Benedict and the time of Louis the Pious. That the daily

monastic allowance would follow this inflationary cycle,

which peaked under Louis the Pious to the impressive

equivalent of 2.12 liters, is impossible to assume. That it

rose to 0.5 liters is probable. There are even some indications

that it might have risen as high as 0.7 liters. A half-liter

of wine per day, if consumed by a healthy man in the

course of two successive meals, could still be interpreted as

lying within the spirit of St. Benedict's ruling; 0.7 liters

would have pushed the Rule to its limit; any amount above

that would have been clearly in violation of the Rule.[240]

My suspicion that the daily allowance of wine might have

risen as high as 0.7 liters at the time of Louis the Pious is

based upon a well known but perhaps not fully explored

passage in the Customs of Corbie, where we are told that in

this monastery each visiting pauper was issued two

245. BOOK OF KELLS. DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE LIBRARY. MS 59, fol. 188r

OPENING WORDS OF ST. MARK GOSPELS

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity College]

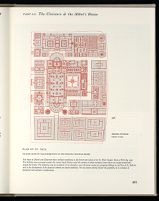

246. PLAN OF ST. GALL

DIAGRAM SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRINCIPAL BUILDING MASSES

The shape of Church and Claustrum bears striking resemblance to the Quoniam initial of the St. Mark Gospels, Book of Kells (fig. 245).

The building masses grouped around this central motif likewise recall the manner in which secondary letter blocks are ranged peripherally

around the initial. The similarity may be accidental, if not deceptive, since the prime reasons for grouping buildings on the Plan of St. Gall (as

well as the development of the claustral scheme) are clearly funtional. Yet one cannot entirely discard the possibility of an interplay of

functional with aesthetic considerations.

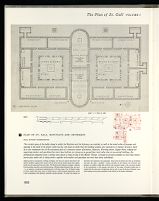

247. PLAN OF ST. GALL. NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY

PLAN. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The circular apses of the double chapel to which the Novitiate and the Infirmary are attached, as well as the round arches of passages and

openings in the walls of the cloister walks (see fig. 236) leave no doubt that this building complex was conceived as a masonry structure. Each

of its two components has all the constituent parts of a monastic cloister (Dormitory, Refectory, Warming Room, Supply Room, lodgings for

supervising teachers and guardians) but since these facilities are strung out on ground floor level rather than in two-storied buildings, this

architectural compound covers a surface area almost as large as that of the Monks' Cloister. It housed in practice probably no more than twelve

novices plus twelve sick or dying monks—together with teachers and guardians not more than thirty individuals.

Differing dietary prerogatives, bathing privileges, and need for special educational and

medical facilities, required that novices and the ill not only be housed apart from regular

monks, but also separated from each other. The Novitiate and Infirmary complex—inspired

by the grandiose centrality and axial bisymmetry of Roman imperial palaces (figs. 240-242)

—is an ingenious architectural implementation of all these needs. Two U-shaped ranges

of rooms around open inner courts, on either side of a church halved transversely, served

a dual constituency with identical, mutually isolated facilities. No doubt the location of

Novitiate and Infirmary was purposeful. Away from the bustle and noise of workshops

and near the open, "parklike" eastern paradise of the Church, the Orchard, and

gardens, its residents might find activities and recreation suited to the returning strength

of the convalescent, or the energies and spirits of the young. Proximity might serve to

remind both ill and novices of beginnings and an end, in view of the great Cemetery cross,

while healing and learning continued in the embrace of the larger community.

passage discloses that the "beaker" of Corbie was capable

of holding 1/96 of a modius[241] which in the light of the

values established by M. B. Guérard for capacity measures

in use at the time when this text was written (A.D. 822)

would amount to 0.7 liters.[242] The passage does not refer

to wine but to beer; however, the relative value of wine

and beer had been defined in 816 in the first synod of

Aachen, in a chapter which directed that if a shortage of

wine were to occur in a monastery, the traditional measure

of wine should be replaced by twice that volume of beer:

ubi autem uinum non est unde hemina detur duplicem eminae

mensuram de ceruisa bona . . . accipiant.[243] This directive was

promulgated as an imperial law and must have been known

to everyone in the empire.

Truly enough the Customs of Corbie speak of rations to

be issued to the poor, not to the monks, but since from

another chapter of that same text it can be inferred that

monks and paupers are entitled to the same ration of

bread,[244]

there is more than a high probability that they

were also granted the same ration of wine or beer. Good

monastic custom would require that an equal amount be

also granted to the serfs. The latter might even have been

issued slightly larger rations because of their involvement

in hard physical labor.

After the evening meal, which was succeeded only by a brief period

of reading and by Compline. See Benedicti regula, chap. 42; ed. Hanslik

1960, 104; ed. McCann, 1952, 100-101; ed. Steidle, 1952, 240-41.

The effect of wine or beer on man depends on the concentration of

alcohol in the blood, and this in turn is dependent on the manner in

which the intake is spaced out over the day and to what extent the

alcohol is diluted by food. Dr. Alfred Childs, an expert on alcohol in the

School of Public Health of the University of California at Berkeley,

advises me that half a liter of wine, spaced out over two meals, and

allowing for some rest after the midday meal, would not have any

damaging effects although it might well involve some temporary impairment

of cerebration during earlier phases of the period during which the

alcohol is metabolized. Even 0.7 liters, if spaced out over two meals and

diluted by food, Dr. Childs opines, might still be within the safety limits

set by St. Benedict (i.e., neither lead to "surfeit" nor "drunkeness")

but would be pushing it close to the edge of these limits. For an analysis

of the metabolism of alcohol, the mechanism of its toxic effects and its

rational use by healthy persons, see Childs, 1970.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 4; ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I

1963, 373; and Jones, III, Appendix II, 105; where it is stipulated that a

quarter of a modius or four sesters of beer be divided daily among twelve

paupers, "so that each will receive two beakers." From this it must be

inferred that there were 96 beakers in a modius (I do not see how Semmler

arrived at the figure of seventy-two. Semmler, 1963, 54). Since in 822

when the Customs of Corbie was written, the official capacity of the

modius was 68 liters, the beaker of Corbie must have been the equivalent

of 0.7 liters. The directive reads as follows: De potu autem detur cotidie

modius dimidius, id sunt sextarii octo, de quibus diuiduntur sextarii quattuor

inter illos duodecim suprasriptos, ita ut unusquisque accipiat calices duos.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||