The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

RULES GOVERNING WORK IN THE KITCHEN |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

RULES GOVERNING WORK IN THE KITCHEN

The management of the kitchen, like that of the refectory,

comes under the jurisdiction of the cellarer, whom

Adalhard warns about getting so immersed in the detail of

chores that can be handled by others, that he may not keep

himself free for the important task of directing and supervising

237. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN & BATHHOUSE OF NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY[208]

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Because of their different diets and remoteness from the Monks' Kitchen and Bathhouse, the planner provided the ill with a kitchen-bath

building adjacent to the infirmary, and a similar kitchen-bath building for the novices symmetrically located on the south. The Plan, in this

part, reveals remarkable responsiveness to administration, practical convenience, and professional care. The walls could have been of masonry

where we show timber construction.

done by the monks themselves, who are assigned to this

task in weekly shifts. Talk is permitted only when the

fulfillment of a chore makes speech inevitable. For the rest

of the time all work is done with the brothers continually

singing psalms.[210]

Laymen and serfs are not permitted in the kitchen.

Adalhard of Corbie is very emphatic on this point and

orders that if laymen assist in the task of preparing and

cleaning the food, "some window, niche, or opening outside

of the kitchen should be set up as a place where the

brothers may pick up the food to be prepared or carry the

food to be washed."[211]

"If there are vegetables to be cleaned or dressed for cooking,

or fish to be gutted or scaled, or beans of different

sorts to be washed or prepared," he adds, "the laymen must

fully and honestly perform these tasks outside the kitchen as

many times as is necessary, and in places assigned for the

purpose. They must use great care to place or stack the

food in a spot where the brothers can conveniently pick it

up. . . . If this procedure is followed, the laymen will not

have to come in to the brothers, nor will the brothers have

to go out to them."[212]

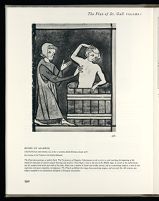

238. ROGER OF SALERNO

CHIRURGIA (13th century), III, 25 fol. 7. (London, British Museum, Sloane 1977)

[by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

The illustration portrays a medical bath. The Chirurgia of Rogerius Salernitanus (1108-1170) is a work marking the beginning of the

medieval renascence of ancient surgical learning and practice. From Roger's time to the end of the Middle Ages, it served as the authoritative

text for surgery both north and south of the Alps. Roger was a student of Greek and Arabic sources, and as a practicing surgeon, a man of vast

experience and great originality of judgement. The Church prohibited the clergy from practicing surgery, and not until the 18th century was

surgery accepted as an autonomous discipline in European universities.

239. ROME. TRAJAN'S BASILICA AND FORUM (DEDICATED 313). PLAN

[after Enciclopedia dell'Arte Antica, VI, 1965, 838, fig. 951]

Platner termed this complex the "last, largest and most magnificent of the imperial fora built by Trajan . . . probably the most impressive and

magnificent group of buildings in Rome." In final form it had five parts: the forum proper; the basilica Ulpia; the column of Trajan; two halls

housing the library; and the great temple of Trajan erected by Hadrian after Trajan's death in A.D. 116. The site dimensions are 185 × 310 m.

The forum itself consists of a rectangular court, with colonnades on three sides and two semicircular exedrae facing each other across the court

in the middle of its two long sides. The court is entered through a central gate in a convex wall contiguous to the forum of Augustus. The

basilica Ulpia lies at the eastern end of this court, its axis at right angles to that of the forum. It is rectangular in plan, five-aisled, with an

apse at each of its two narrow ends, and three monumental portals on the long side facing the forum. Two doors in the opposite wall give access

to the small, open court that accommodates in its center the famous column of Trajan, whose pedestal served as a sepulchral chamber for the

emperor's ashes and whose shaft displays reliefs arranged in a spiral band, representing the principal events of Trajan's campaign in Dacia

(A.D. 101-106). The rest of the court is taken up by two halls housing the library, one for Greek, the other for Latin manuscripts.

In the east the forum terminates in a monumental hemicycle, in the axis of which Hodrian erected the great temple honoring Trajan and his

wife Plotina. The ruins of the temple of Trajan were eventually covered by almost two millennia of rubble. But during the Carolingian period its

buildings, although damaged, were probably sufficiently well preserved to convey an accurate image of their original appearance and composition.

The real disintegration occurred in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, when Rome began to grow again and the ruins of the ancient city

were quarried by everyone needing building materials.

The culmination of interest in this great expanse of magnificence and splendor is the

Column of Trajan, A.D. 114.

Of special interest, set above the doorway to the sepulchral chamber in the base of the

shaft, is a single stone about nine feet wide and a little less than four feet high. On this

stone is to be seen a dedicatory inscription, carved and composed in six lines of lettering

created and executed in a manner never surpassed and rarely equalled.

Here, one finds exemplified "a monumental writing such as the world has not seen since"

(David Diringer). Roman capital letters, capitales quadratoe, attained the level of their

highest perfection in the first and second centuries A.D.

Roman letters of this excellence (on the tomb of a great emperor, flanked on each side by a

library for manuscripts) became symbols that helped shape learning and education in the

renaissance of Charlemagne. The Roman letter prevails today. The display type used in

this book, designed by Eric Gill, himself a cutter of letters in stone, is directly related to

the Roman model cut in stone.

E.B.

240.A TRIER. AULA OF IMPERIAL PALACE

PLAN (4th century)

The aula, whose axis runs from south to north is 67 × 30 × 27.5m.

It was preceded by a monumental narthex and terminates in the

north in a large apse, which contained the emperor's throne. The

entire floor of the hall (nearly 1700 sq. m.) was underpinned by a

hypocaust system with tubes in the long walls carrying heat to a

height of 8m. The aula was flanked on either side by a narrow

colonnaded court. While the precise layout of these courts became

known only through recent excavations, it is possible that in

Charlemagne's time they were still intact. They might therefore have

exerted a direct influence on the creation of concepts embodied in the

layout of the Novitiate and Infirmary of the Plan of St. Gall.

The illustration, figure 237, shows the facility for Novices. The

Infirmary facility is identical but of opposite hand, i.e. flopped plan.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 5; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 384, and Jones, III, Appendix II, 109.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 5; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 385: "But to keep these matters from slipping from anyone's

mind, because of some earlier code, we herewith briefly formulate the

three principles underlying all these statements: that is, either keep quiet

if the matters are not essential, or say what is necessary, or else chant

psalms" and Jones, III, Appendix II, 110.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||