The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

Refectory |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

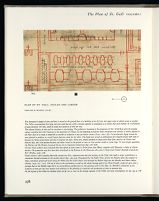

Refectory

TABLES AND BENCHES

The Plan provides us with a complete and detailed

account of the furnishings of this hall (fig. 211). It shows in

the center of the eastern, or upper, half of the hall the

"table of the abbot" (mensa abbatis), a

with two arms 30 feet long, and a connecting head piece 10

feet long. Two longitudinal benches (scammum, aliud) range

along the arms of the table. The center is left free for easy

access by the servers. The abbot's table has a total length of

70 feet and can seat twelve persons on each of its long arms

and four at its head, if we allow 2½ feet per person. Parallel

to the abbot's table, on either side of the hall, are two

L-shaped tables, each having a total length of 40 feet,

providing space for sixteen persons per table. These tables

are served by a single continuous wall bench which ranges

around the circumference of the entire eastern half of the

hall (sedes in circuitu) and also serves the abbot's table. The

combined seating capacity of the upper portion of the hall

is sixty: twenty-eight at the abbot's table, sixteen at the

southern wall table, and sixteen at the northern wall table.

The seating arrangement in the western or lower half of

the hall is different. It consists of a straight center table

(mensa) with benches on either side (sedile, aliud) 27½ feet

long, permitting sitting space for twenty-two persons, and

two L-shaped wall tables along the southern and northern

walls of the hall, identical with the corresponding tables in

the upper end of the hall, each seating nineteen persons.

The total seating space at the lower end of the hall, despite

the different layout, is the same as that in the upper half,

viz., twenty-two at the center table, nineteen at the southern

wall table, and nineteen at the northern wall table,

equaling sixty. The grand total for the entire hall is 120,

not counting the table for the visiting monks (ad sedendū cū

hospitibus), which provides six additional seats, corresponding

exactly to the number of beds available in the

lodging for the visiting monks.[100]

The table for the visiting

monks stands in front of the reader's pulpit.

READER'S PULPIT

The reader's pulpit (analogium) is marked by a square

with a circle inside and appears to be raised on a platform.

In later times the reader's pulpit generally consisted of a

semicircular balcony with lectern corbelled out from the

wall and accessible by a stairway built into the wall. A good

example is the reader's pulpit in the refectory of the

Cistercian monastery of Poblet, Catalonia (fig. 212).[101]

In

even better states of preservation are the pulpits of the

refectories of the priory of St.-Martin-des-Champs at

Paris,[102]

the cathedral of Chester (Cheshire),[103]

and the

Abbey of Beaulieu (Hampshire).[104]

Traces of others are

found in many ruined abbeys, such as Tintern and

Fountains.[105]

The pulpit of the Refectory of the Plan of St.

Gall, however, is square, not semicircular or polygonal like

the later examples. Moreover, the layout of the wall

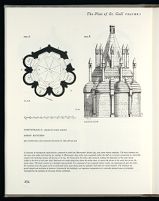

217. PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' KITCHEN

Interpretation by Völckers

[after Völckers, 1949, 27]

218. WOODCUT FROM KUCHEMAISTREY, AUGSBURG,

1507

[after Schiedlausky, 1956, 22]

Kitchen with cook and maid. Völckers' reconstruction is handsome,

but incompatible with the inscription FORNAX SUPER ARCUS, "a

stove supported by arches." Square stoves on arches with firing

chambers and cooking wells must have been common in Antiquity as

well as in the Middle Ages, as figs. 218-221 show.

not allow access to a stairway built into the wall itself. I am

inclined to think that the pulpit was reached by an open

stairway.

The reader's pulpit faces the entrance to the Refectory,

which lies in the middle of the southern cloister walk. The

symbol used for this entrance differs from that of any other

door on the Plan. It suggests a double door arrangement

with entrance and exit separated by a median wall partition,

such as are used as standard passageways even today in

countless churches, in England as well as on the continent.

CUPBOARDS

The only other piece of furniture found in the Refectory

of the Plan of St. Gall is a double square referred to as

toregma. Square symbols designated by this term are found

in two other places on the Plan, in each case within a dining

area, in the Abbot's House, and in the House for Distinguished

Guests (figs. 251 and 396). Keller interpreted these

storing vessels" (Refectory),[108] "a vessel for washing hands"

(Abbot's House),[109] and "chairs or cushioned seats" (House

for Distinguished Guests).[110] Willis interpreted them as

"presses,"[111] Stephani as "cupboards,"[112] and Lesne as

"waterfountains."[113]

The confusion stems from the spelling of the term

toregma (plural, toregmata) which is otherwise unattested,

and must be equated with the common word toreuma,

which denotes either embossed metal objects (including

statuary) or turned wooden objects, or the products in

general of the woodworkers' craft (again extending to

statuary). Du Cange under the word tornarius, i.e.,

"turner," states that a tornarius or tornator made toreumata.

Since most of the plates and bowls from which the

monks ate and in which their food was served were

wrought on the turner's lath,[114]

I am inclined to think that

toregma or toregmata relates to the bowls and vessels used

219. GEORGIUS AGRICOLA. DE RE METALLICA, LIBRI XII, BOOK X, BASEL, 1556

SEPARATION OF GOLD AND SILVER WITH AQUA VALENS

[after H. C. and L. H. Hoover, trans., London, 1912, 446]

Agricola's woodcut portrays a furnace of the same construction type as the stove in the Monks' Kitchen, except in size. It is described in the

text:

"The furnace is built of bricks, rectangular, two feet long and wide and as many feet high and a half besides. It is covered with iron plates . . .

which have in the center a round hole and on each side of the center hole two small round air holes. The lower part of the furnace, in order to

hold the burning charcoal, has iron plates at the height of a palm . . . In the middle of the front there is the mouth, made for the purpose of

putting fire into the furnace; this mouth is half a foot high and wide, and rounded at the top, and under it is the draught opening."

Georgius Agricola (baptised Georg Bauer, 1494-1555) was a German expert in mining methods and metallurgical processes who wrote the first

systematic treatise on these subjects. His informative and richly illustrated De re metallica, published in Basel in 1556, remained until the

18th century the authoritative handbook on mining. It owed its spectacular success to the author's broad knowledge of classical learning, acute

power of empirical observation, and thorough acquaintance with technical installations used in the operation of mines.

which this ware was stored. A twelfth-century manuscript

in the British Museum, the Psalter of Henry of Blois,

gives us a good idea how such a piece of furniture may have

looked (fig. 213),[115] and a handsome woodcut by Michael

Wohlgemut in the Schatzbehalter of Nuremberg (1491)

shows such a cupboard in its setting, on a page that depicts

a royal banquet (fig. 214).[116] A beautiful Tyrolian cupboard

of the same variety, dating from the thirteenth or fourteenth

century, exists in Burg Kreuzenstein (fig. 215).[117]

Others, no less impressive, dating from the thirteenth to

the sixteenth centuries, may be found in Our Lady's

Church in Halberstadt (fig. 216),[118] the Church of Schulpforta,[119]

and the Museum of Wernigerode,[120] the Cathedral

of Halberstadt,[121] and the Museum of Lübeck.[122] The most

monumental of all is a great thirteenth-century ambry in

the Cathedral of Chester.[123]

Niermeyer (Med. Lat. lex. min., fasc. 11, 1964, 1032) glosses

toreuma as "couch," "curtain" and "cupboard" with sources for all of

these meanings. "Curtain" I find a little puzzling. But "couch" makes

perfect sense, since the majority of the component parts of such a piece

of furniture (like that of the church bench, shown above p. 152, fig. 100)

were made of pieces of wood turned on the lathe.

The author cited as source for "cupboard" is Ruodlieb, a writer who

had "more than a casual knowledge of Greek", and the passage, in his

courtly eleventh century novel, referred to by Niermeyer is of impeccable

non-ambiguity:

Mensa sublata properat sustollere uasa

Ne mingat catta catulusque coinquinet illa,

sedulus ac lauit, post in toreuma reponit.

which Zeydel translates:

"When the table had been removed, he hurries to clear away the

dishes,

lest the cat urinate on them or the dog soil them.

With care he washes them and then puts them in the closet."

(Ruodlieb, VI, 45-48, ed. Zeydel, 1959, 82-85; on Ruodlieb's proficiency

in Greek, ibid., 23.)

To "be turned" or serve as a container for objects produced on the

turner's lathe appears to be the common denominator for the majority

of the multiple meanings of the term toreuma. But the term was subjected

to considerable strain by its medieval users. Charles Jones draws my

attention to a passage in Einsiedeln Ms. 172, saec. X, a Commentary on

Donatus (ed. Hermann Hagen in Keil, Grammatici Latini, VIII, 1870

(1961), 239, but repunctuated), wherein everything after balteus puerilis

is a marginal addition: "τορεύω Graece torno, inde toreuma dicitur tornatura

uel balteus puerilis—siue id quod eicitur de tornatura uel bullae quae in

stillicidio apparent plauiali tempore. (Ad quorum similitudine calceoli

fiebant nobilium puerorum, per quod designabatur quod, quamdiu his

utebantur, alterius consilio indigebant; nam βουλή Graece consilium, inde

βουλετής consiliarius.) Aliter hami loricarum ita uocantur." Jones translates:

"τορεύω in Greek means `torno.' From this toreuma comes to mean

`turner's ware' [uide Irminonis polypt. i, 34], or `a boy's belt' [balteus

comes also to mean `palisade' (Niermeyer)]—or whatever is derived

from turner's ware, or little balls (bullae) such as the hail that appears in

a downpour during the rainy season. (They fabricate the sabots of

noble boys out of bulbous discs shaped like that; and as long as the

boys wear that kind of sabot, it shows that they still need supervision of

someone else, for βουλή in Greek means `counselling,' hence βουλετής

means `counsellor.') Elsewhere, the studs on breastplates are called

toreuma."

LACK OF FACILITIES FOR HEATING

As one analyzes the layout of the Monks' Refectory one is BEGINNING OF 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. [after Parrot, 1958, fig. 21] Five kitchen stoves forming a single range constructed of unfired

struck by the observation that this large hall has no

facilities for heating. It is provided neither with a hypocaust,

nor with the kind of open fireplace that forms the

central source of warmth in the guest and service buildings,

nor with any corner fireplaces such as are provided to warm

the bedrooms of the higher ranking officials of the monastery,

and those of the distinguished guests.[124]

It is impossible

to look upon this omission as an oversight. The Refectory

obviously was not meant to be heated. The only source of

warmth available to this hall was the body heat of the people

who assembled there during the meal hours which in the

cold of the transalpine winters must often have been passed

in an uncomfortable chill. This willful rejection of physical

comfort surely can only be interpreted as a retention in

ceonobitic medieval monachism of the ascetic attitudes of

220. MESOPOTAMIA. PALACE OF MARI

bricks, with cooking wells and firing chambers all still containing

charcoal, were found when this kitchen was excavated in 1935-1938.

The entire range was so well preserved that it could have been put

into operation without repair.

221. POMPEII. HOUSE OF THE VETII

[after Mau, 1908, 274]

This hearth is in essence merely a large square base, on the top of

which meals are cooked with the aid of charcoal braziers. A rim

around the edges of the cooking surface prevents cinders or ashes

from falling on the floor. The hole at the bottom of the hearth is for

storing of firing materials. But a hearth of identical construction

with a corresponding opening serving as firing chamber is represented

on a 2nd-century Roman relief at Igel near Trier (see Singer et

al, II, 1956, 119, fig. 89).

even contemptible activity, gluttony no less than a venal

sin. Again it was St. Benedict who reinstituted the meal as

a normal function of life. One eats in order to live. Yet in

furnishing the body with what is needed for its sustenance,

one should not take more than is required for that purpose.

Under no circumstances should one allow the meal or the

refectory to become a preoccupation of the mind or the

senses, or allow oneself to indulge in any form of excess.

St. Benedict expresses himself in unequivocal terms on this

point: "Above all things, gluttony must be avoided"

(remota prae omnibus crapula).[125] Rendering the refectory

chilly and uncomfortable would reduce the temptation to

linger over one's food unduly, and would prevent in large

measure untoward enjoyment of what was served. To impose

silence on those who congregated at the table, and

direct their attention to the lessons of the Reader, were

further means to forestall any unwarranted engrossment

with the physical pleasures of eating.

A full account of the heating devices used in the various installations

shown on the Plan of St. Gall can be found in II, 117ff.

Benedicti regula, chap. 39; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 100; ed. McCann

1952, 94-95; ed. Steidle, 1952, 235.

LAYOUT OF TABLES AND BENCHES IN

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

By contrast to this conspicuous disregard for comfortable

standards in heating, the physical layout of the tables and

benches in the Monks' Refectory is sophisticated and most

carefully planned. The designing architect must not only

have had accurate instructions concerning the number of

people the Refectory was to accommodate in a single

sitting, but also must have been fully aware of the precise

needs in linear length of the tables and benches required to

meet this condition.[126]

He solved his problem, as we have

seen, by placing two tables in the center, and four along

the walls of the room. The details of this concept pose

fascinating, if unanswerable historical questions, into a

discussion of which I enter in full awareness of its highly

tentative and speculative nature.

The desert monks thought so little of eating (or so much

of its dangers!)[127]

that many of them preferred to ingest

their food while standing or walking around. Of Father

Sisoës it is said that he frequently did not know whether or

not he had already taken his meal.[128]

Tables on which to

spread one's food, or chairs to sit upon while taking a meal,

were incompatible with this concept and even the comfort

offered by a simple stone or the crude stump of a tree, in

this mode of thinking, was looked upon as a source of

sensuous self indulgence. But when St. Pachomius took the

epochal step of renouncing his hermitic past and founding,

in a desolate place called Tabenissi, on the river Nile the

first systematically organized community for monks, he

furnished this monastery with a refectory where the monks

took their meals seated at tables. They had to do this in

rigid silence, their heads covered by their cowls, so that

their eyes would only see the bowls from which they ate,

and could not stray aside to look at any of the other monks.

Yet no one was forced to come to the table and St. Pachomius,

in fact considered it to be a higher form of religious

attainment if a monk chose to dispense with the regular

food either through fasting or relying on only the slimmest

diet of bread, water, and salt which his superior, upon

request, could allow him to take to his cell.[129]

While many may have chosen these individual forms of

dietary ascetism as the more desirable path in their search

for salvation, in a community whose population reached at

its peak the staggering figure of 2,500 monks, the number

of those who attended the common meal must still have

been sufficiently large to call for a substantial and carefully

planned arrangement of tables and benches. The only

other sphere of life where men in comparable numbers

assembled for a common meal must have been the eating

halls of permanent Roman military camps, with the layout

of which St. Pachomius must have been well acquainted

from the days when he served in the Roman army.[130]

It is

MARMOUTIER, INDRE-ET-LOIRE, FRANCE. KITCHEN

222.A

222.B

PLAN

[after Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire Raisonné, IV, 1858, 462 and 463]

Like the Kitchen shown in fig. 223, this one is a masterpiece of functional construction. A natural fire hazard, this type of kitchen (whether

monastic or secular) is invariably built as a separate entity a short distance from the eating hall, precisely as shown on the Plan of St. Gall

(fig. 122). From the 12th century onward they were generally built in masonry, often in the shape of an inverted funnel and ventilated by a

multitude of chimneys. The kitchen of Marmoutier has an external diameter of roughly 12m. It had five hearths installed in five niches, each

with one central (A) and two lateral (B) chimneys. Three further chimneys emerge from the shell higher up in the vault, which terminates in a

large central chimney (K) forming the top of the building. The stereotomy in structures of this type is almost beyond belief, and in an exterior

view appears to defy gravity. Six arches of the Marmoutier interior support six squinches which, in turn, support a second set of six squinches.

On these, the inverted masonry funnel rides magically on a circle of incredible shear stress.

monachism also probably owed the concept of its wall

enclosure,[131] —that we may have to look for the ultimate

source for both the layout of the Pachomian refectory and

its Roman prototypes and Carolingian derivatives.

When monachism spread to the north, however, the

monastic refectory may have been exposed to another

secular influence, namely the large and festive banqueting

halls that played such an important role in the life of the

Germanic kings and chieftains. In the traditional Germanic

FONTEVRAULT, MAINE-ET-LOIRE, FRANCE

223.A

223.B

ABBEY KITCHEN

[after Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire Raisonné, IV, 1858, 468 and 470]

A structure of unsurpassed sophistication, compared to which the Marmoutier kitchen (fig. 222) seems almost simplistic. The basic elements are

the same: five niches with hearths for cooking. In Marmoutier these niches were contained within the shell of a structure presenting an externally

smooth and continuous surface all the way to its top. At Fontevrault the niches sally outward, making the disposition of the inner spaces

visible in the form of the outer shell. Buttresses are raised along lines where the niches meet, to receive the thrust of the vault that covers the

center space. The latter consists of a daringly steep pyramid. It is composed of two octagonal cloister vaults, one superimposed upon the other,

the transition from the square of the arch-framed center space being made by squinches with holes for smoke emission. The chimneys are

pencil-shaped and terminate in lanterns. Structurally this building is an ingenious transposition to a centrally planned space of principles

developed by the architects of the great Gothic cathedrals.

such as that of Hall Heorot in the Beowulf poem[132]

(eighth century; but reflecting a tradition that reaches considerably

farther back) and the realistic accounts of

banquets in the Nordic sagas (ninth to twelfth centuries)[133]

—the retainers sat at tables and benches ranged along the

walls of the house throughout the entire length of the

building. The host sat on a high seat in the middle of one

of the two aisles of the hall, his guest of honor on a corresponding

seat in the middle of the opposite aisle. A cross

bench at the inner end of the room was taken up by women.

The fire burned in the middle of the center floor, from which

the food and the drinks were served. Only on very rare

occasions, i.e., when the number of guests was so large that

not all of them could be accommodated in the aisles of the

house, was the center floor taken up by an additional row

of tables and benches.[134] On such occasions the physical

layout of the Germanic banqueting hall, indeed, bore close

resemblance to that found in monastic refectories, although

there still remained an important difference: in the monastic

refectories, the highest ranking person, the abbot, sat on

the cross bench at the upper or eastern end of the hall; the

entrance was in the middle of the long wall facing the

cloister. This arrangement is more closely related to that

of the later feudal halls (especially well known in England)

where the lord dined on an elevated platform (dais) in the

uppermost bay of the building, at a table placed crosswise

to the long tables, while his retainers sat at tables ranging

lengthwise down the aisles of the hall.[135] The location of

the table for the abbot, "the representative of Christ in the

monastery,"[136] at the eastern head of the refectory unquestionably

has its origins in the Christian ritual, which in

turn was deeply influenced by the ceremonial of the Roman

imperial court. The latter was also the ultimate source of

the exalted position of the table of the medieval feudal lord,

to whom I presume, this concept was transmitted by their

royal overlords, after they assumed the successorship of the

emperors of Rome.

Cf. our remarks on the architect's awareness of precise scale

relationships, see above, pp. 77ff.

On the refectory and the rules which govern eating in the Pachomian

monasteries, see Grützmacher, 1896, 120-21; paragraph 5 of

Jerome's preface to his translation of the Rule of St. Pachomius (Boon,

1932, 7) and chaps. 29-36 of the Rule (Boon, 1932, 20-22). For the

occurrence of the terms mensa and sedere, see index of Boon's edition.

The earliest monastic Refectory table known to me, if Sawyer's date

of this building is correct (ca. A.D. 350), is that of the communal eating

hall of the Coptic monastery Dair Baramus. See Sawyer, 1930, 324-25

and Pl. VIII, facing 321.

On the table and table customs in ancient Rome see the article

mensa in Pauly-Wissowa's Real-Encyclopädie, VI:1, 1931, cols. 937-948.

But little, if anything, seems to be known about the seating arrangement

in the mess halls of Roman military camps (see fig. 211).

On the walls enclosing the Pachomian monasteries of Egypt, see

above, p. 71; on other architectural and organizational features, below

p. 327 n2.

On the arrangement of the tables and benches in the banqueting

halls of North Germanic chieftains of the Saga period, see II, 23 on the

setting up of special tables and benches in the nave of the hall, ibid., II,

24.

On the layout of tables and benches in medieval feudal halls see

II, figs. 339 and 346D; Horn, 1958, 9.

Benedicti regula, chap. 2; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 19; ed. McCann 1952,

17; ed. Steidle, 1952, 79. Cf. below, p. 323.

NUMBER AND HOURS OF MEALS OF THE MONKS

The number and hours of the meals of the monks are

regulated in Chapter 41 of the Rules of St. Benedict.[137]

The schedule set forth there is, as Dom David Knowles has

put it, "so foreign to anything in modern life, even among

religious orders . . . that it is difficult, when reconstructing

it in the imagination, to appreciate where its physical

handicaps lay and where use had become second nature.[138]

During the winter, beginning with the thirteenth of

September and ending with Ash Wednesday, the monks

were allowed a single full meal per day which was eaten

about two o'clock in the afternoon. The same schedule

prevailed for the time of Lent, but in this period the meal

was served after Vespers, i.e., about half past five or six.

During the summer months, and on all Sundays and Feast

Days, the monks ate two meals, one at midday, the other

about six o'clock in the evening. This schedule made

allowance for a rest after the midday meal.

The most perplexing aspect of this schedule of meals, in

the eyes of a modern observer, "is the assignment of the

first meal to a time never less than ten, and throughout the

winter of about twelve hours after rising."[139]

The change

from a winter schedule of one meal to a summer schedule

of two, providing for a midday rest, is of course the product

of the Mediterranean climate, in which monachism

originated. There "the heat of the summer makes a siesta

after the midday meal all but a physical necessity."[140]

North of the Alps this routine was senseless, yet the force

of tradition was so strong that it remained unmodified by

any difference of climate or latitude throughout the entire

Middle Ages.

Benedicti regula, chap. 41; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 102-104; ed. McCann,

1952, 98-99; ed. Steidle, 1952, 238-39.

Knowles, 1950, 449, whom I am following closely, at times verbatim,

in the following paragraphs.

THE MONKS' DIET

St. Benedict prescribes that every meal of the monks

"should have two cooked dishes, on account of individual

infirmities, so that he who perchance cannot eat of the one,

may make his meal of the other . . . and if any fruit or

young vegetables are available, let a third be added.

(Sufficere credimus ad refectionem cotidianam tam sextae quam

nonae omnibus mensis cocta duo pulmentaria propter diuersorum

infirmitatibus, ut forte, qui ex illo non potuerit edere,

ex alio reficiatur . . . et si fuerit, unde poma aut nascentia

leguminum, addatur et tertium).[141]

Hildemar, in commenting

on this chapter, points out that in contrast to the biblical

tradition where the term pulmentum is used for a considerably

broader range of dishes (including meals made of

venison), it is applied by St. Benedict exclusively to cooked

dishes made "of vegetables, of cheese and eggs, and of

flour" (de oleribus, de caseo et ovis et de farina). He adds to

this that if the term is used without the qualifying adjective

coctum it refers to uncooked dishes, "in which something is

added to bread to make it better eating such as cheese, the

leaves of leek [greens in general?] or egg, or other similar

things" (quidquid pani adijicitur, ut melius ipse panis

comedatur, sicuti est caseum et folia porrorum et ovum et

CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND. KITCHEN, BISHOP'S PALACE

224.A

224.B

224.C

RECORDED BY THE AUTHORS, 1960

With its simple square form and timbered roof, the kitchen of the bishop's palace at Chichester reflects the tradition of the Monks' Kitchen of

the Plan of St. Gall (fig. 211) more closely than the elaborate structures of Fontevrault and Marmoutier (figs. 222-223), with their

sophisticated masonry skills in arching and vaulting that one would scarcely expect to antedate the Romanesque and Gothic periods.

The roof frame of Chichester, despite its primitive appearance, is nevertheless a highly evolved form of early English hammerbeam construction

that apparently did not emerge before the end of the 13th century, and which became very fashionable shortly thereafter. It is formed of four

trusses springing from trussed brackets suspended in the masonry walls, and was surmounted at its apex by an open lantern, now concealed by a

modern ceiling added early in the 20th century. Certain constructional similarities of the scantling of the bishop's palace with that of St. Mary's

Hospital in Chichester (figs. 341-343) suggest a late 13th- or early 14th-century date.

bread per day—St. Benedict calls it a "weighed pound"

(panis libra una propensa), i.e., a quantity of bread whose

mass was controlled by weighing it on the scales rather

than by the estimate of the baker or servers.[142] On days on

which two meals were served, one third of this allowance of

bread was to be put aside for the evening meal.

"Except the sick who are very weak, let all abstain

entirely from the flesh of four-footed animals" (Carnium

uero quadripedum omnimodo ab omnibus abstineatur comestio

praeter omnino deuiles egrotos). St. Benedict states his views

about the inadmissibility of meat from quadrupeds clearly

enough, but frustrates his modern readers by not giving any

reasons for this injunction. His ninth-century commentator

Hildemar fortunately comes to aid in this matter: "It is on

account of its pleasurable taste, not because of the number

of feet that monks are known to abstain from the meat of

four-footed animals" (et ideo propter suavitatem gustus, non

propter numerum pedem abstinentes et poenitentes a carnibus

abstinere noscuntur) . . . "For the desires of the flesh are

more easily aroused where greater delight and pleasure is

encountered in the food (eo quod stimuli carnis magis solent

insurgere ubi major dulcedo et major suavitas gustus in cibum

percipitur). He points to the example set by Christ and by

the apostles, as well as by leading monastic authorities "of

none of whom we read in scripture or in Church history

that they ate any meat other than fish"; and concludes his

argument with a quotation from the fifth book of the

institutae patrum, where it is said that "the food of the

monks must be such as to contribute to the sustenance of

life, but not such as to arouse the desires of flesh and to

subminister to vice" (ut ille cibus debeat esse monachorum,

qui sustentationem tribuat vitae, non ille, qui occasionem

concupiscentiis et vitiis subministrat).[143]

The consumption of fowl was a controversial matter on

which St. Benedict had failed to express himself. This was

interpreted by many to mean that he condoned it. The

reform movement of Benedict of Aniane attempted to

eliminate the uncertainties that arose from this lack of

specific legislation, but the directives issued at Aachen

contradict, even annul, each other. The synod of 816 barred

the consumption of poultry, except in case of sickness (Ut

uolatilia intus forisue nisi pro infirmitate nullo tempore

comedant).[144]

The council of 817 admitted it for the great

feasts of Christmas and Easter for a period of eight days

each (Ut uolatilia in Natiuitate Domini et Pascha tantum

octo diebus si fuerit unde aut qui uoluerit comedant).[145]

A later

capitulary reduced this span to four days.[146]

A second controversial issue taken up at Aachen concerned

the question whether St. Benedict, in barring the

flesh of quadrupeds from the monks' table, also eliminated

the use of fats extracted from these creatures. Since his own

monastery, Monte Cassino, lay in one of the richest olive-producing

regions of Italy, it is probable, as Semmler has

pointed out,[147]

that this question did not even enter his

mind. North of the Alps, where olive oil was not available

in sufficient quantity to satisfy the needs of the monks'

kitchen, animal fats became a basic necessity.[148]

Benedict

of Aniane, after initially barring its use in the kitchen of his

own monastery, eventually felt himself constrained to

rescind this order.[149]

The synod of 816 adopted this more

moderate view and formally permitted the use of animal

fats for cooking, except on Fridays, the twenty days before

Christmas, and the period between Sunday Quinquagesima

and the feast of Easter.[150]

This custom was universally

adopted, with the exception of Adalhard of Corbie,

who retained the position that fat from quadrupeds was

meat and therefore subject to St. Benedict's injunction.[151]

The Rule permitted each monk a hemina of wine per day,

and the synod of 816 expanded this allowance, so when

wine was not available in sufficient quantity, it could be

replaced by twice its measure in beer.[152]

The diet of the monk thus consisted of bread, a variety of

dishes made of pulse, fresh vegetables and fruit when in

season, a good measure of wine or beer, poultry at certain

periods of the year, every variety of fish, and of course the

entire gamut of dairy and poultry products such as milk,

cheeses, and eggs. The Consuetudines Sublacenses contains

a paragraph from which we may learn what, at the time of

its writing, was considered a typical monastic menu:

But today in the monastery of Subiaco this custom is followed:

when there are two meals a day, namely on Sunday, Tuesday, and

Thursday, at the midday meal a course (ferculum) of chickpeas (de

ciceribus) and of earth products (tellerinis) as well as a custard (subtestum)

of eggs, cheese, and milk, and also fruits which are in season

are put on the table. And on the same days, for the evening meal, a

fried dish (una frictura) of eggs, or two fresh eggs prepared some

225. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CELLAR AND LARDER

SAME SIZE AS ORIGINAL (1:192)

The monastery's supply of wine and beer is stored on the ground floor of a building 40 by 87½ feet, the upper story of which serves as Larder.

The Cellar accommodates five large and nine small barrels, with a storage capacity so calculated as to insure that each member of a community

of approximately 300 men, could be issued one HEMINA of wine per day.

The cultural history of wine and its containers is fascinating. The prehistoric homeland of the grapevine (VITIS VINIFERA) were the wooded

regions extending from the Caucasus to the mountains of Thrace. At the beginning of historic times viticulture was already so widely diffused in

the Near East as to make it impossible to ascribe its inception to any particular country (Lutz, 1922, 1ff). In pre-dynastic Egypt vineyards

were planted to produce as a royal luxury funerary wines for its rulers. The liquid was stored in earthenware jars smeared inside with resin or

bitumen for better preservation and also to improve its taste. These jars, almost identical in shape with those later used by the Greeks and

Romans (fig. 226), had pointed bottoms and either rested in the ground or were set into wooden stands or stone rings. To store larger quantities,

the Hittites and the Romans increased the jar size to impressive dimensions (figs. 227-228).

Certain Greek authors were convinced that the culture of vines came to Greece from Asia Minor, together with Dionysios, a deity of Asiatic

descent. The grapevine may first have been introduced to the Romans by the Etruscans who came to Italy from Central Anatolia around 900

B.C. (Forbes, 1956, 128).

Greek colonists, after founding Marseille around 600 B.C., imported wine into the territory of the Celts, who made a major contribution to

viticulture through invention of the wooden barrel (figs. 229-234). Propagated by the Gallic Celts, and by the Romans after the conquest of

Gaul, viticulture penetrated north along the Rhône and the Saöne Rivers and through the Belfort Gap into the Moselle and Rhine valleys

(Forbes, 1956, LOC. CIT.). The use of wine in the sacraments, as well as the solemn homage paid it by Christ himself, conferred upon wine a

prestige that in the Middle Ages led to an extraordinary proliferation of vine growing north of the Alps. St. Benedict's allowance of one

HEMINA of wine per day lent impetus and authority to the planting of vineyards and production of wine in monastic life.

On the layout of the Cellar by modular grid, see fig. 70, p. 102; on the storage capacity of the Cellar and wine consumption, see fig. 235, p. 186

should be prepared, for example, a course of beans (fabae) or peas

(pisellae) or cabbages (caulae) and so forth and afterward fresh

cheese with leftovers (recocta) or fishes with fruits in season. For

dinner a cooked course with cheese and fruits. . . .[153]

Apples, or any other fruit that is eaten raw, were divided

equally among the brothers by the cellarer and laid out on

the tables before the monks were seated.[154]

Outside the

regular mealtime the eating of fruit or any other sort of

fresh vegetables was forbidden.[155]

Benedicti regula, chap. 39; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 99-100; ed. McCann,

1952, 94-97; ed. Steidle, 1952, 234-35.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 441-42, commenting

on chapter 39 of the Rule of St. Benedict, Hanslik, McCann and Steidle,

loc. cit.

Verhulst and Semmler, 1963, 54. Scruples and doubts about the

justifiability of this legislation continued to persist, as witnessed by

Hildemar, who writes "the meat of fowl has an even more enticing

flavor than that of four-footed animals, as the learned men point out,

and as is confirmed by practice, in that kings and princes in their festive

gatherings insist that because of its sweeter and more delightful flavor,

after the meat from quadrupeds, the meat of fowl be served" (plus

dulces carnes habere volatilia, quam quadrupedia, sicut doctores dicunt et

usus comprobat in eo, quod reges et principes propter majorem dulcitudinem

et suavitatem gustus post carnes quadrupedum in suis conviviis carnes

volatilium praecipiunt sibi praeparari). Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller,

1880, 441.

See "Vita Benedicti abbatis Anianensis," chap. 21; ed. Waitz,

Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. XV:1, 1887, 209.

Cf. Semmler, 1963, and notes to chap. 20 of the decreta authentica

of the first synod, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 463.

MONKS' BEHAVIOR DURING THE MEAL

The monks' behavior at mealtime is described in a compilation

of monastic customs which was written toward the end

of the eighth century, and appears to have been held in such

esteem by Benedict of Aniane that he proposed to promulgate

it by attaching it to the capitulary of 817.[156]

As the hour of the meal approaches, upon completion of

the divine service, the monks wait in the choir, softly singing

psalms. At the first sound of the bell, they walk to the

refectory in order and, after having washed their hands,

salute the cross with their faces turned east. When the bell

rings again they kneel, say a verse, and recite the Lord's

Prayer. Then the prior blesses the monks, the brothers

take their seats at the table, each at his proper place, and

thereafter they remain in complete silence.

The boys are not seated separately, but are intermixed

with their elders, two at each table.[157]

In Corbie the boys

took their meals standing opposite their teachers.[158]

"If

anyone does not arrive before the verse, so that all may say

the verse and the prayers together and all at the same time

go to the table . . . he shall be corrected once and a second

time for this. If he still do not amend, he shall not be

allowed to share the common meal; but let him be separated

from the company of the brethren and take his meal alone,

and be deprived of his allowance of wine, until he do penance

and amend."[159]

The food is served from the kitchen, beginning at the

lower end of the refectory, near the kitchen, where the

most recently admitted monks are seated and ending with

the abbot at the upper, eastern end of the hall. When the

bell rings a third time, the abbot blesses the bread and

breaks it, and the brothers, after blessing each other in

turn, begin to partake of their food. The lector ascends the

pulpit and commences his reading.

When the time comes to serve the wine, the cellarer

motions to the server, and immediately upon this signal the

junior brothers rise from their seats and fill the cups for

the monks.[160]

In carrying out this task they lower their

heads, first to the Cross, then to the abbot, and finally in

a circle to all of the brothers, whereafter they return to

their seats.

If there is anything the brothers need as they eat and

drink they must supply it to one another, so that no one

shall have to ask for anything. Should need arise, nevertheless,

that something must be requested, it must be done

by a sign rather than by speech.[161]

When all the food is

eaten, the reader stops his recitation, the brothers say a

verse, rise from the table—the left-hand choir first, the

right-hand choir next, and the abbot last—singing the

fiftieth psalm. They enter the church in this manner, "bow

to the Gloria," say the Lord's Prayer, and then proceed to

the chapter "silently, as befits the time."[162]

Memoriale Qualiter; ed. Morgand, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 177282;

see chap. 5, De Refectione, ibid., 254-58.

Benedicti regula, chap. 43; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 108-110; ed. McCann,

1952, 103-5; ed. Steidle, 1952, 242-43.

According to the Capitula in Auuam directa (806-822), chap. 7 (ed.

Frank, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 335) this task was performed by "8 to

10 monks."

Benedicti regula, chap. 38; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 98-99; ed. McCann,

1952, 92-95; ed. Steidle, 1952, 233-34.

THE READER

The reader is appointed for the entire week and enters

upon his office on Sunday, after having received the blessing

of his brothers in the preceding service. Before he

ascends the pulpit he is given some bread and wine, and he

takes his full meal only after the monks have eaten, together

with the servers and kitcheners.[163]

A chapter of the first

synod of Aachen amplifies this tradition by stipulating that

he should not receive anything else beyond what is granted

to him by the Rule.[164]

The lector's reading is supervised by the corrector, who

sits beside him on the pulpit. If need be, the latter rises,

looks into the book and corrects the Reader "gently"

(leniter).[165]

Benedicti regula, chap. 38; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 99; ed. McCann,

1952, 94-95; ed. Steidle, 1952, 234.

THE SERVERS

The Rule prescribes that no one be excused from service

in the kitchen and in the refectory unless he be engaged in

some more important task or is prevented by sickness.

However, if the community is large, the cellarer may be

relieved from this duty altogether.[166]

In entering upon their

weekly duty on Sundays, immediately after Lauds, the

incoming servers, together with those whom they relieve,

226. POMPEII [after Billiard, 1931, 184. fig. 70]

Tavern sign of burnt clay showing the common Roman amphora used for

transport and storage of standardized quantities of wine.

227. NÎMES, MAISON CARRÉE. ROMAN DOLIUM

The largest extant Roman DOLIUM, displayed on the podium of the

Maison Carrée in Nîmes, near the Cella entrance. The height of the

person standing to the right is 74 inches, ca. 1.88m. (photo: Horn).

ask for their prayers. An hour before the meal, all are

given, over and above their regular allowance, a drink and

some bread, "in order that at the meal time they may serve

their brethren without murmuring and undue hardship."[167]

The servers set the tables, bring in the food and take away

what is left. In cleaning the tables after the meal they brush

the crumbs into a canister with a broom made for that

purpose.[168]

As they serve the food they must see to it that

those who eat are not in want of any food or drink, that the

brothers are not given less than the abbot, the juniors not

less than the seniors, except for the boys who receive a

smaller portion.[169]

If they distribute more or less than is

right, or perform their tasks noisily, or if they neglect,

lose, spill, or break something, or create damage in any

other way, they must immediately ask for indulgence by

throwing themselves on the ground before the prior, holding

in their hand that which they have damaged, and telling

what has happened.[170]

After the monks have eaten, the

servers take their own meal "not at one table but each in

his proper place," and while they eat "the same texts that

were recited to the others, will be recited to them."[171]

At the end of their weekly term the outgoing servers

wash the towels the brethren use for drying their hands and

restore the vessels to the cellarer "clean and sound." Then

the cellarer delivers them to the monk whom he has placed

in charge of the incoming servers "in order that he may

know what he is giving out and what receiving back."[172]

Then together the outgoing and the incoming servers wash

the feet of the whole community.[173]

Benedicti regula, chap. 35, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 92-95; ed. McCann,

1952, 86-89; ed. Steidle, 1952, 226-28.

Letter addressed to Abbot Haito of Reichenau by two of his monks

after the synod of 817; see Capitula in Auuam directa, chap. 7; ed. Frank,

Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 335.

Capitula in Auuam directa, loc. cit.; and Memoriale Qualiter, chap. 4;

ed. Morgand, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 245.

For a detailed description of this, see Consuetudines Sublacenses,

chap. 23, ed. Albers, Cons. mon., II, 1905, 164.

WHO IS ADMITTED BESIDE THE MONKS

The question of who was to be admitted to the refectory

was never settled to everybody's satisfaction. In order to

protect the life of the monks from being contaminated

by association with visitors from the outside world, St.

Benedict provided the abbot with his own kitchen, "so

that the brethren may not be disturbed when guests—

who are never lacking in a monastery—arrive at irregular

hours."[174]

This rule had always been a source of annoyance

to reform-eager souls, and the resulting uncertainties are

reflected in conflicting legislation. Chapter 14 of the synod

of 817 rules "that layman should not be conducted into the

refectory for the sake of eating and drinking" (Ut laici in

refectorium causa manducandi uel bibendi non ducantur),[175]

but a directive which appears to have been issued not before

818-819 eased this directive by admitting ecclesiastics

of superior rank, and noblemen.[176]

Some abbots, such as

Adalhard of Corbie, went even further by making this

privilege available to paupers and secular canons of lower

ranks.[177]

Other monasteries retained the more restrictive

customs of earlier periods, as is suggested by a passage in

Ekkehard's Casus sancti Galli, which reads:

The monastery of St. Gall, as I come to speak about this place, has

always been held in such high veneration from the oldest memory

of our fathers, that no one, not even the most powerful canon or

227.X BOǦAZKÖY, ANKARA, TURKEY, TEMPLE 1

This large pithos lies in the ground of a storeroom of the great Hittite temple built

between 1275 and 1220 B.C. by the kings Hattusli III and Tudhalya IV [photo: Horn]

228. BOSCOREALE, CAMPAGNA, ITALY

[after Billiard, 1931, 476, fig. 163]

Cave of a Roman wine merchant with large DOLIA buried in sand, a method used by

the Hittites as early as the mid-second millennium B.C.

229.B MAINZ. MITTELRHEINISCHES LANDESMUSEUM

Remains of a Roman barrel found in a bog, filled with the remains of fillets of fish

[photo courtesy Mittelrheinisches Landesmuseum].

229.A HAITHABU. SCHLESWIG-HOLLSTEIN, GERMANY

Wine barrel re-used in an upright position as a well lining [photo courtesy

Schleswig-Hollsteinisches Landesmuseum für Vor-und Frühgeschichte].

enclosure or even to glance into it.[178]

Infractions of this rule are carefully recorded by Ekkehard,

such as the time when King Conrad I surprised the monks

of St. Gall, on December 26 of the year 911, by entering

the refectory in the company of two bishops, with the word

"With us you shall have to share your meal whether you

wish or not!" and at the same time instructing Abbot

Salomon not to join the party in the refectory but to

preside over the table of the king's retainers in the House

for Distinguished Guests—a complete reversal of the roles

of abbot and emperor.

The entry of laymen into the refectory could be legalized,

however, by the act of confraternization, often performed

on such occasions, and on the day after Conrad's first unauthorized

entry into the refectory at St. Gall he petitioned

to be voted in confraternity by the monks. This was granted

him, and at the noon meal of the same day he again shared

their company, during which the monks were treated to

delicacies not permitted on their regular diet. "No one

complained that this or that was contrary to custom,"

concludes Ekkehard's account of this unusual event, "although

nothing like this had ever been heard or seen before,

or even experienced by a monk in this house."[179]

Benedicti regula, chap. 53; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 123-26; ed. McCann,

1952, 120-23; ed. Steidle, 1952, 257-61; for further details, see below,

pp. 321ff and above, p. 22.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||