The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

METHOD OF HEATING |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

METHOD OF HEATING

The heating system of the Monks' Warming Room raises

interesting historical and technological questions. It consists,

as already pointed out, of an external firing chamber

(caminus ad calefaciendū) that transmits its heat to the

building through heat ducts (not shown on the Plan), the

necessary draft for which is generated by an external smoke

stack (euaporatio fumi).

Identical heating units appear in two other places on the

Plan, the "warming room" (pisale) of the Novitiate and

the "warming room" (pisale) of the Infirmary.[58]

Keller's[59]

attempt to interpret these devices as simple fireplaces is

untenable and was convincingly repudiated by Willis.[60]

They are clearly descendants of the Roman hypocaust

system. The existence of such heating systems in the

Middle Ages is well attested both by literary and archeological

sources. A hypocausterium almost contemporary with

those of the Plan of St. Gall was built by Abbot Ewerardus

at the monastery of Freckenhorst.[61]

An excavation conducted

in 1939 at Pfalz Werla, one of the fortified places of

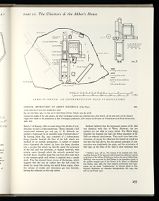

201. LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804). ISOMETRIC RECONSTRUCTION

[after Selzer, 1965, 148]

The abbey grounds, of irregular ovoid shape, were surrounded by a masonry wall. Entering the monastery from the west the visitor stepped into

a large rectangular atrium where he had to pass through what can only be called the Carolingian equivalent of a Roman triumphal arch

accommodating over its passages a small royal hall (a jewel of Carolingian architecture, built 768-774, the earliest wholly preserved building of

post-Roman times on German soil). At the end of this atrium the visitor faced two massive towers flanking a gate that gave access to a second,

considerably smaller atrium lying before the monumental westwork of the church of St. Nazarius, an aisled basilica with low transept and

probably a rectangular choir, built between 767-774, and enlarged eastward in 876 by a crypt for royalty. The component building masses of

this architectural complex rose in dramatic ascent on successively higher levels of the gently rising slope of a natural sand dune; the west gate at

the bottom, the choir of the church at the top, the late Carolingian crypt eight meters below the level of the church on the steeply descending

east slope of the dune.

The walls of the monastery enclosed an area of roughly 25,000 square meters. Forming a veritable VIA SACRA, from gate to altar the route of

passage was nearly 260m. long.

LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804).

200.X

200.

12TH-CENTURY PLAN AND ISOMETRIC VIEW

Fig. 200: after Behn, 1964, 117; Fig. 200.X: after Hubert, Porcher, Volbach, 1970, fig. 377.B]

Toward the middle of the 12th century, the inner Carolingian atrium was converted into a fore church. At the same time, all the claustral

ranges were rebuilt on the foundations of their Carolingian predecessors. (For remains of the latter see Vorromanische Kirchenbauten,

1966, 180).

of such a hypocausterium. There, beneath a hall

constructed between 920 and 930, C. H. Seebach unearthed

a hypocaust in an excellent state of preservation.[62]

Its heating plant (fig. 209) consisted of a subterranean

firing chamber beneath the floor of the hall, which was

reached by an outside passageway. A system of radiant

ducts channeled the heated air from the firing chamber

into a circular flue which lay directly under the pavement

of the hall and was provided, at regular intervals, with

tubular vents through which the warmth ascended into

the hall above. Another large flue ran from this main duct

to the western gable wall where it emptied into a smoke

stack. This flue showed heavy traces of blackening, which

suggests that the hot air outlets into the hall could be

closed by stone lids during the initial firing stages, when

the volume of smoke and obnoxious gas was heaviest,

leaving the chimney as the only outlet.

Seebach believes that the hypocaust system of St. Gall

was identical with that of Werla. However, the two

systems are not alike in every detail. The Werla firing

chamber lay beneath the hall; the firing chambers of St.

Gall are external attachments. They must have been subterranean,

of course, for otherwise the heated air could not

rise into the hall above, but the general principle of construction

was doubtlessly the same, and the occurrence of

this type on the Plan of St. Gall is clear testimony that

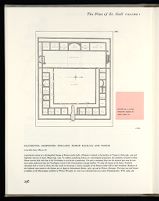

202. SILCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND, ROMAN BASILICA AND FORUM

PLAN (after Joyce, 1887, pl. 16)

A provincial variant of a distinguished lineage of Roman market halls, Silchester is related to the basilicas of Trajan in Rome (fig. 239) and

Septimius Severus in Lepcis Magna (fig. 159). To students considering history as a chronological progression, the similarity of layout of these

Roman market halls with that of the Carolingian CLAUSTRUM is perplexing. Yet such a conceptual leap into the classical past may be even

more easily understood than the Carolingian revival of the Constantinian transept basilica. To study the layout of the latter, Frankish

churchmen had to travel to Rome, but they could see surviving or ruinous examples of the Roman market hall in their homeland. Basilicas of

the Silchester type existed in the Roman city of Augst in Switzerland (Reinle, 1965, 34) and in Worms, Germany. The latter was well known

to builders of the Merovingian cathedral of Worms (Fuhrer zu vor-und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, XIII, 1969, 36).

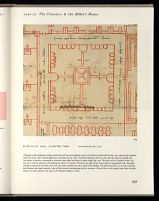

203. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CLOISTER YARD

Although in plan displaying striking similarities with the great galleried courts of the Roman market halls (cf. figs. 202, 239) the four-cornered

medieval cloister shows marked differences in elevation (cf. fig. 192). The Roman basilican courts are vast areas for open-air assembly and

the conduct of business, surrounded by relatively small offices and shops of modest height (fig. 202). The open yard of a medieval cloister, by

contrast is small in relation to the buildings by which it is enclosed. The latter rise high and are surmounted by steep-pitched roofs. Internally,

although composed of two levels, they form open halls extending the entire length of the building. The galleried porches are the only connecting

links between these huge structures, none of which possess interconnecting doors or entrances. The tint block on the opposite page shows the above

cloister (100 feet square) at the scale of the Silchester basilica (1:600).

204. DIOSCURIDES. MATERIA MEDICA

Vienna, National Library, CODEX VINDOBONENSIS, fol. 48v

SAVIN PLANT (JUNIPERUS SABINA)

[by courtesy of the National Library of Vienna]

Pedanios Dioscurides of Anazarbos, a physician of Greek descent

who served in the army of Nero, wrote his Materia Medica around

50 A.D. It details the properties of about 600 medicinal plants and

describes animal products of dietetic and medicinal value. The writing

of Dioscurides was well known and widely read in the Middle Ages

and served as a standard text for learning in all medical schools.

The illustration shown above is from a richly (in places even

brilliantly and very realistically) illuminated copy of this treatise

executed by a Byzantine artist in 512, and now available in a

magnificent facsimile edition.

ducts, and a chimney stack for draft and evacuation of

obnoxious gas were, at the time of Louis the Pious, a

standard system used in the construction of monastic

warming rooms. Whether or not the heat produced by this

system could also be conducted into the Dormitory above

remains a moot question.

Nec ab incoepto destitit donec in circuitu oratorii refectorium hiemale et

aestivale, hypocaustorium, cellarium, domum areatum, coquinam, granarium et

dormitorum, et omnia necessaria habitacula aedificavit." (Vita S. Thiadildis

abbatissae Freckenhorsti; see Schlosser, 1896, 86, No. 283). For previous

discussions of the hypocausts of St. Gall see Keller, 1844, 21; Willis,

1848, 91; Stephani II, 1903, 77-83; Oelmann, 1923/24, 216.

Seebach, 1941, 256-73. The remains of the channels and a freestanding

chimney of the hypocaust which heated the calefactory and the

scriptorium of the Abbey of Reichenau, built at the time of Abbot Haito

(806-823), were excavated by Emil Reisser in the immediate vicinity of

the nothern transept arm of the Church of St. Mary's at Mittelzell

(see Reisser, 1960, 38ff). For other medieval calefactories with hypocausts,

see the article "Calefactorium" by Konrad Hecht in Otto

Schmidt, Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, III, 1954, cols.

308-12; and Fusch, 1910.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||