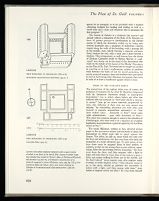

LAYOUT OF THE BEDS

The layout of the beds in the Monks' Dormitory is complex

and ingenious. We have already discussed the manner

in which it was designed in our analysis of the scale and

construction methods used in designing the Plan.[43]

The

number 77 is not likely to be an accident.[44]

Yet I have been

able to find only one instance where the number of monks

was confined to this figure.[45]

The Monk's Dormitory, like the two other principal

buildings of the cloister, the Refectory and the Cellar, has

no internal architectural wall partitions whatsoever, and for

that reason must be thought of as a unitary space, open from

end to end. This should not be interpreted to mean, however,

that the beds were in full and open view of everyone

throughout the entire length and width of the building.

They must have been separated from one another by

wooden panels sufficiently high and long to protect the

monks from interfering with one another. The Custom of

Subiaco stipulates "that there be wooden partitions between

bed and bed, so that the brothers may not see each

other when they rest or read in their beds, and overhead

they must be covered [with canopies] because of the dust

and the cold." The same custom also requires "that these

spaces be so arranged, as to be provided with a window

admitting daylight for reading and writing as well as a

small table and a chair and whatever else is necessary for

that purpose."

[46]

The Custom of Subiaco is a relatively late source[47]

and

already reflects a relaxation of the Rule of St. Benedict in

favor of greater privacy—a development in the further

course of which the dormitory ended up by being subdivided

internally into a sequence of individual cubicles

ranged along the walls of the building, with a passage left

in the middle, each cubicle forming a separate enclosure

fitted, besides the bed, with a chair and a desk beneath a

window. This arrangement, so well known from the dorter

of Durham Cathedral (built by Bishop Skirlaw in 13981404)[48]

was clearly not in the mind of the churchmen who

ruled on the details of the layout of the Monks' Dormitory

on the Plan of St. Gall. Yet even here we might be justified

in counting on at least a rudimentary system of partition

walls between the beds—if not for moral protection, for

purely practical reasons: since the brothers were permitted

to read in bed during their afternoon rest period, they were

in need of at least a headboard against which to lean.