The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. | III.1.5 |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III. 3. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

III.1.5

DORMITORY AND WARMING ROOM

On the Plan of St. Gall the building that contains the

Dormitory of the Monks bounds the cloister to the east and

lies in direct axial prolongation of the transept of the

church (fig. 208). It is a double-storied structure, 40 feet

wide and 85 feet long. The ground floor serves as the warming

room, the upper floor is the dormitory (subtus calefactoria

dom', supra dormitorium). A hexameter inscribed into

the adjacent cloister walk informs us that this building can

be heated:

Porticus ante domun st& haec fornace calentem.

Let this porch stand before the hall which is heated by

a furnace.

The plan of this building comprises elements of both the

lower and the upper story. The seventy-seven beds of the

monks (lecti, similt) as well as the doors that open from

this building to the transept of the church, to the cloister,

and to the monks' privy are obviously related to the

dormitory. The "exit from the warming room" (egressus

de pisale), which leads to the monks' bath house, on the

other hand, and the large "firing chamber" (caminus ad

calefaciendū) as well as the "smoke stack" (euaporatio

fumi) which are attached to the eastern wall of the building,

relate to the calefactory on the ground floor.

Dormitory

HOW THE MONKS ARE TO SLEEP

How the monks are to sleep is set forth in chapters 22 and

55 of the Rules of St. Benedict. According to these, each

monk must have his separate bed, assigned to him in

accordance with the date of his conversion. If possible, all

of the brethren should sleep in one room; but if their

number does not allow this, in groups of ten and twenty,

with seniors to supervise them. The young monks may not

sleep in a group among themselves, but interspersed with

their elders. A light must burn in the dormitory throughout

the night and the monks must sleep "clothed and girt with

girdles or cords," so that they can rise without delay when

the signal calls them to the work of God. They must not

sleep "with their knives at their sides lest they hurt themselves."

"When they rise for the work of God," St. Benedict

advises, "let them gently encourage one another, on account

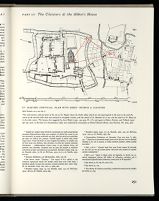

196. ST. RIQUIER (CENTULA)

ANGILBERT'S CHURCH AND CLOISTER (790-799)

[after Effman, 1912, fig. 1]

The original manuscript of Hariulf's Chronicon Centulense,

written before 1088, (ed. Lot, 1894) perished in fire in 1719. It

contained Hariulf's drawing of the Carolingian abbey church and

cloister still in their original condition. His drawing is known through

two copies. The earliest and most authentic (above) was made in

1612 and published in Petau's De Nithardo Caroli magni

nepote, Paris, 1913. Our knowledge of the exterior of the

Carolingian church is derived from it. The interior layout was

reconstructed independently, with virtually the same results, by

Georges Durand (1911) and Wilhelm Effmann (1912) through

analysis of the description of religious services and liturgical

processions in Hariulf's chronicle. The best plan, because it takes into

account irregularities in the Gothic church reflecting conditions of its

Carolingian predecessor, is that of Irmingard Achter, 1956 (figs. 135

and 168).

In waking each other, as Hildemar informs us in more

detail, "the wise and older monk will arouse the brother

who sleeps next to him . . . but no junior monk should ever

arouse another junior, because of the temptation this may

offer for sin (propter occasionem peccati); rather one or two

seniors, after having lit a candle, will walk through the

dormitory to wake the sleepy brothers; yet, in performing

this duty will never touch the brother but only a board of

his bed or something similar."[36]

For bedding they are allowed: a mattress (matta), a

blanket (sagum), a coverlet (lena), and a pillow (capitale).

The possession of any personal property other than that

which is issued to all of the brothers[37]

is severely prohibited,

and in order to guard against infractions of this regulation

the beds are frequently inspected by the abbot.[38]

We must assume that the beds were provided with some

locker or storage space, in which the monks could keep the

duplicate set of clothing which the Rule permitted them

"to allow for a change at night and for the washing of these

garments."[39]

During the hours which are set aside for sleeping,

whether in the day or at night, silence is vigorously enforced

in the dormitory;[40]

but on certain specified periods

of the daily cycle, such as when the monks return from

their chapter readings, they may engage in conversation, in

groups of two or three or more.[41]

Even during the midday

rest in the summer, conversation is permitted, provided

that it does not "injure the peace of those who sit and read

in bed." Should there be any need for sustained talk, the

monks must go outside (i.e., to the cloister walk) and

conduct their business there.[42]

Singuli per singula lecta dormiant; lectisternia pro modo conuersationis

secundum dispensationem abbae suae accipiant. Si potest fieri, omnes in uno

loco dormiant; sin autem multitudo non sinit, deni aut uiceni cum senioribus,

qui super eos solliciti sint, pausent. Candela iugiter in eadem cella ardeat

usque mane. Uestiti dormiant et cincti cingulis aut funibus, ut cultellos suos

ad latus suum non habeant, dum dormiunt, ne forte per somnum uulnerent

dormientem . . . Adulescentiores fratres iuxta se non habeant lectos, sed

permixti cum senioribus. Surgentes uero ad opus Dei inuicem se moderare

cohortentur propter somnulentorum excusationes. Benedicti regula, chap. 22;

ed. Hanslik, 1960, 77-78; ed. McCann, 1952, 70-71; ed. Steidle, 1952,

200-201.

See below under "Vestiary." The synod of 817 added to the

standard equipment which the monks could keep near their beds, a

specified supply of soap and unction; Synodi secundae decr. auth. chap.

38; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 480.

Benedicti regula, chap. 55; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 130; ed. McCann,

1952, 126-27; ed. Steidle, 1952, 269.

Benedicti regula, chap. 55; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 129; ed. McCann,

1952, 124-25; ed. Steidle, 1952, 269.

Consuetudines Corbeienses; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963,

417: "Quando uero dormiendi tempus fuerit siue in die siue in nocte silentium

funditus in ore, ita in incessu, ut nullus iniuriam patiatur, summa cautela

esse debet."

Ibid., 416-17: "Quando loqui licet, quia locutio semper ibi seruanda

est siue duo seu tres seu aetiam plures sicuti fieri solet quando de capitulo

surgunt coniungantur."

Ibid., 417: "Quod si aliquis etiam ad legendum in lectulo suo resederit,

nequaquam alterum sibi ibidem ad colloquium coniungat, sed si

necessitatem loquendi diutius habuerint, exeant foras et ibi loquantur."

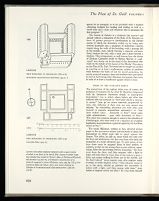

LAYOUT OF THE BEDS

The layout of the beds in the Monks' Dormitory is complex

and ingenious. We have already discussed the manner

in which it was designed in our analysis of the scale and

construction methods used in designing the Plan.[43]

The

number 77 is not likely to be an accident.[44]

Yet I have been

able to find only one instance where the number of monks

was confined to this figure.[45]

The Monk's Dormitory, like the two other principal

buildings of the cloister, the Refectory and the Cellar, has

no internal architectural wall partitions whatsoever, and for

that reason must be thought of as a unitary space, open from

end to end. This should not be interpreted to mean, however,

that the beds were in full and open view of everyone

throughout the entire length and width of the building.

They must have been separated from one another by

wooden panels sufficiently high and long to protect the

monks from interfering with one another. The Custom of

Subiaco stipulates "that there be wooden partitions between

bed and bed, so that the brothers may not see each

other when they rest or read in their beds, and overhead

they must be covered [with canopies] because of the dust

and the cold." The same custom also requires "that these

197. ST. RIQUIER (CENTULA). PLAN WITH ABBEY CHURCH & CLOISTER

[after Durand, 1911, 241, fig. 5]

This 19th-century cadastral plan of the city of St. Riquier shows the Gothic abbey church (1) and superimposed in the area to the south the

course of the covered walks that once enclosed its triangular cloister, with the church of St. Benedict (2) in one, and the church of St. Mary (3)

in the other corner. This layout, first suggested by Jean Hubert (1957, 293-309, Pl. 1.C), and again in Hubert, Porcher, and Volbach (1970,

297, fig. 341), on the basis of a documentary study, was confirmed by excavations of Honoré Bernard (Karl der Grosse, III, 1965, 370).

199. LORSCH

FIRST MONASTERY OF CHRODEGANG (760-774)

AXONOMETRIC RECONSTRUCTION [after Behn, 1949, pl. 1]

198. LORSCH

FIRST MONASTERY OF CHRODEGANG (760-774)

PLAN [after Selzer, 1955, 14]

Lorsch is the earliest medieval monastery with a square cloister

attached to one flank of the church. But a layout of similar shape

may already have existed in Pirmin's abbey of Reichenau-Mittelzell,

built between 724 and 750, if Erdmann's reconstruction of its

claustral compound is correct (Erdmann, 1974, 499, fig. TA 4). For

Lorsch see Behn and Selzer, and a more recent summary by

Schaefer in Vorromanische Kirchenbauten, 1966-68,

179-82.

admitting daylight for reading and writing as well as a

small table and a chair and whatever else is necessary for

that purpose."[46]

The Custom of Subiaco is a relatively late source[47]

and

already reflects a relaxation of the Rule of St. Benedict in

favor of greater privacy—a development in the further

course of which the dormitory ended up by being subdivided

internally into a sequence of individual cubicles

ranged along the walls of the building, with a passage left

in the middle, each cubicle forming a separate enclosure

fitted, besides the bed, with a chair and a desk beneath a

window. This arrangement, so well known from the dorter

of Durham Cathedral (built by Bishop Skirlaw in 13981404)[48]

was clearly not in the mind of the churchmen who

ruled on the details of the layout of the Monks' Dormitory

on the Plan of St. Gall. Yet even here we might be justified

in counting on at least a rudimentary system of partition

walls between the beds—if not for moral protection, for

purely practical reasons: since the brothers were permitted

to read in bed during their afternoon rest period, they were

in need of at least a headboard against which to lean.

Sit tamen inter lectum et lectum intersticium tabularum, quod prohibeat

mutuam visionem fratrum in lectis jacencium vel legencium; sintque desuper

cooperti propter pulveres et frigus. Loca eciam sic sint ordinata, ut quilibet

habeat fenestram pro lumine diei ad legendum et scribendum et mensulam

ibidem collacatam atque sedem et hujusmodi que necessaria sunt pro talibus.

(Conseutudines Sublacenses, chap. 3, ed. Albers. Cons. Mon., II, 1905,

125-26.)

The oldest preserved manuscripts of the Consuetudines Sublacenes

(St. Gall Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Lat. 928 and 932) date from around 1436.

See Albers, 1902, 201ff.

FEARS OF THE VIGILANT ABBOT

The eternal fear of the vigilant abbot was, of course, the

pollution of monastic life by what St. Benedict designated

with his distinctive discretion simply as impropriety

(improbitas),[49]

but to which others before and after him

referred with less restraint as "that habit which is contrary

to nature" (usus qui est contra naturam) perpetrated by

men, who oblivious of their own sex turn nature into

iniquity "by committing shameless acts with other men

(masculi in masculos turpitudinem operantes),[50]

or "that

most wicked crime . . . detestable to God" (istud scelus

valde nefandissimum . . . quae valde detestabile est Deo).[51]

The crime was common enough to come to the attention of

Charlemagne, who dealt with it in a vigorous act of public

legislation, incorporated in a general capitulary for his Missi

issued in 802.[52]

The monk Hildemar, writing in 845, devoted several

pages to this precarious subject and discussed in detail the

precautions an abbot must take to guard against this

danger. The abbot, he tells us, must watch not only over

the boys and adolescents, but also over those who enter the

monastery at a more advanced age. To each group of ten

boys there must be assigned three or four seniors, or

masters, so that no one among them is ever without supervision.

After the late evening service, Compline, "the boys

must leave the choir, and their masters, with a light in

hand, will take them to every altar of the oratory to pray a

little, one master walking in front, one in the middle, and

the third behind" (unus magister ante, alter magister vadat

in medio, et tertius magister retro); "then whoever wants to

go to the privy, should go perform the necessities of

nature with a light, and their master with them" (cum

lumine et magister eorum cum illis).[53]

If a boy finds himself

must waken his master, who will light a lamp and take him

to the privy, and with the light burning, bring him back

to bed."[54] Even the dreamlife of the monks and its sexual

connotations are subject to supervision. Depending on the

varying degree of sleep or consciousness, the employment

of the senses of touch and vision, or the extent of deliberate

procrastination, the offense must be atoned for by the

recitation of psalms, five, ten, or fifteen respectively, and

if the indulgence was committed with no restraint, by the

reading of the entire psalter.[55]

Benedicti regula, chap. 2 and 23; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 24, 79; ed.

McCann, 1952, 20-22, 72-73; ed. Steidle, 1952, 82-83, 200-201.

"For a most pernicious rumor has come to our ears that many in

our monasteries have already been detected in fornication and in abomination

and uncleanness. It especially saddens and disturbs us that it can

be said, without a great mistake, that some of the monks are understood

to be sodomites, so that whereas the greatest hope of salvation to All

Christians is believed to arise from the life and chastity of the monks,

damage has been incurred instead. Therefore, we also ask and urge that

henceforth all shall most earnestly strive with all diligence to preserve

themselves from these evils, so that never again such a report shall be

brought to our ears. And let this be known to all, that we in no way dare

to consent to those evils in any other place in our whole kingdom; so

much the less, indeed, in the persons of those whom we desire to be

examples of chastity and moral purity. Certainly, if any such report

shall have come to our ears in the future, we shall inflict such a penalty,

not only on the guilty but also on those who have consented to such

deeds, that no Christian who shall have heard of it will ever dare in the

future to perpetrate such acts." (Here quoted after translations and

Reprints, VI, Laws of Charles the Great, ed. D. C. Monro, n.d., 21.

For the original text see Capitulare Missorum Generale, AD 802, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Legum II, Capit. I, 1883, 94.)

ABSENCE OF STAIRS

The author of the Plan of St. Gall did not consider it a

matter of vital importance to express himself in great detail

about the stairs which connected the Dormitory with the

Church, the cloister, and the privy. He made it absolutely

clear, however, where such connections should be established.

There is no doubt that the door that leads from the

Dormitory to the southern transept arm of the Church

must have opened onto a flight of stairs by which the

monks descended into the Church for their nocturnal services.

A direct ascent to the dormitory a parte ecclesiae in

the Abbey of St. Gall is mentioned in Ekkehart's Casus

sancti Galli.[56]

Flights of night stairs of precisely this type

survive in an excellent state of preservation in the transepts

of the Cistercian abbey churches of Fontenay and Silvacane,

both from about 1150, and the Benedictine abbey

church of Hexham (fig. 101), from about 1200-1225.[57]

The

area in the middle of the Dormitory left unobstructed by

beds might have been meant to serve as landing for an inner

stair connecting Dormitory with Warming Room. This

same stair could also have been used for daytime access

from ground level to Privy, which to judge by numerous

later parallels must have been level with the Dormitory.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 91; ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 322ff; ed. Helbling, 1958, 164ff. Cf. II, 327.

For night stairs in general see Aubert, I, 1957, 304-305. For

Fontenay, see Ségogne-Maillé, 1946, fig. 5; for Silvacane: Pontus, 1966,

38; for Hexham: Cook, 1961, pl. VII and Cook-Smith, 1960, pl. 39.

A night stair survives in the north transept of Tintern Abbey. Others in

varying degrees of preservation are found in many other medieval

churches (Beaulieu Abbey; St. Augustine, Bristol; Hayles Abbey, and

others). The remains of the earliest medieval flight of dormitory night

stairs known to me are those which have been excavated by Otto Doppelfeld

in the northern transept arm of Cologne Cathedral. They are virtually

coeval with the Plan of St. Gall. See Weyres, 1965, 395ff and 417,

fig. 5.

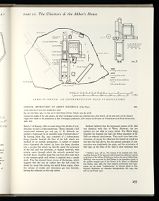

Warming room

METHOD OF HEATING

The heating system of the Monks' Warming Room raises

interesting historical and technological questions. It consists,

as already pointed out, of an external firing chamber

(caminus ad calefaciendū) that transmits its heat to the

building through heat ducts (not shown on the Plan), the

necessary draft for which is generated by an external smoke

stack (euaporatio fumi).

Identical heating units appear in two other places on the

Plan, the "warming room" (pisale) of the Novitiate and

the "warming room" (pisale) of the Infirmary.[58]

Keller's[59]

attempt to interpret these devices as simple fireplaces is

untenable and was convincingly repudiated by Willis.[60]

They are clearly descendants of the Roman hypocaust

system. The existence of such heating systems in the

Middle Ages is well attested both by literary and archeological

sources. A hypocausterium almost contemporary with

those of the Plan of St. Gall was built by Abbot Ewerardus

at the monastery of Freckenhorst.[61]

An excavation conducted

in 1939 at Pfalz Werla, one of the fortified places of

201. LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804). ISOMETRIC RECONSTRUCTION

[after Selzer, 1965, 148]

The abbey grounds, of irregular ovoid shape, were surrounded by a masonry wall. Entering the monastery from the west the visitor stepped into

a large rectangular atrium where he had to pass through what can only be called the Carolingian equivalent of a Roman triumphal arch

accommodating over its passages a small royal hall (a jewel of Carolingian architecture, built 768-774, the earliest wholly preserved building of

post-Roman times on German soil). At the end of this atrium the visitor faced two massive towers flanking a gate that gave access to a second,

considerably smaller atrium lying before the monumental westwork of the church of St. Nazarius, an aisled basilica with low transept and

probably a rectangular choir, built between 767-774, and enlarged eastward in 876 by a crypt for royalty. The component building masses of

this architectural complex rose in dramatic ascent on successively higher levels of the gently rising slope of a natural sand dune; the west gate at

the bottom, the choir of the church at the top, the late Carolingian crypt eight meters below the level of the church on the steeply descending

east slope of the dune.

The walls of the monastery enclosed an area of roughly 25,000 square meters. Forming a veritable VIA SACRA, from gate to altar the route of

passage was nearly 260m. long.

LORSCH, MONASTERY OF ABBOT RICHBOLD (784-804).

200.X

200.

12TH-CENTURY PLAN AND ISOMETRIC VIEW

Fig. 200: after Behn, 1964, 117; Fig. 200.X: after Hubert, Porcher, Volbach, 1970, fig. 377.B]

Toward the middle of the 12th century, the inner Carolingian atrium was converted into a fore church. At the same time, all the claustral

ranges were rebuilt on the foundations of their Carolingian predecessors. (For remains of the latter see Vorromanische Kirchenbauten,

1966, 180).

of such a hypocausterium. There, beneath a hall

constructed between 920 and 930, C. H. Seebach unearthed

a hypocaust in an excellent state of preservation.[62]

Its heating plant (fig. 209) consisted of a subterranean

firing chamber beneath the floor of the hall, which was

reached by an outside passageway. A system of radiant

ducts channeled the heated air from the firing chamber

into a circular flue which lay directly under the pavement

of the hall and was provided, at regular intervals, with

tubular vents through which the warmth ascended into

the hall above. Another large flue ran from this main duct

to the western gable wall where it emptied into a smoke

stack. This flue showed heavy traces of blackening, which

suggests that the hot air outlets into the hall could be

closed by stone lids during the initial firing stages, when

the volume of smoke and obnoxious gas was heaviest,

leaving the chimney as the only outlet.

Seebach believes that the hypocaust system of St. Gall

was identical with that of Werla. However, the two

systems are not alike in every detail. The Werla firing

chamber lay beneath the hall; the firing chambers of St.

Gall are external attachments. They must have been subterranean,

of course, for otherwise the heated air could not

rise into the hall above, but the general principle of construction

was doubtlessly the same, and the occurrence of

this type on the Plan of St. Gall is clear testimony that

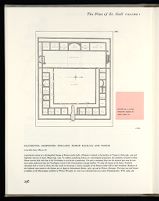

202. SILCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND, ROMAN BASILICA AND FORUM

PLAN (after Joyce, 1887, pl. 16)

A provincial variant of a distinguished lineage of Roman market halls, Silchester is related to the basilicas of Trajan in Rome (fig. 239) and

Septimius Severus in Lepcis Magna (fig. 159). To students considering history as a chronological progression, the similarity of layout of these

Roman market halls with that of the Carolingian CLAUSTRUM is perplexing. Yet such a conceptual leap into the classical past may be even

more easily understood than the Carolingian revival of the Constantinian transept basilica. To study the layout of the latter, Frankish

churchmen had to travel to Rome, but they could see surviving or ruinous examples of the Roman market hall in their homeland. Basilicas of

the Silchester type existed in the Roman city of Augst in Switzerland (Reinle, 1965, 34) and in Worms, Germany. The latter was well known

to builders of the Merovingian cathedral of Worms (Fuhrer zu vor-und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, XIII, 1969, 36).

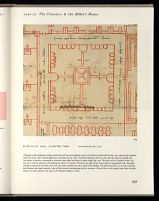

203. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CLOISTER YARD

Although in plan displaying striking similarities with the great galleried courts of the Roman market halls (cf. figs. 202, 239) the four-cornered

medieval cloister shows marked differences in elevation (cf. fig. 192). The Roman basilican courts are vast areas for open-air assembly and

the conduct of business, surrounded by relatively small offices and shops of modest height (fig. 202). The open yard of a medieval cloister, by

contrast is small in relation to the buildings by which it is enclosed. The latter rise high and are surmounted by steep-pitched roofs. Internally,

although composed of two levels, they form open halls extending the entire length of the building. The galleried porches are the only connecting

links between these huge structures, none of which possess interconnecting doors or entrances. The tint block on the opposite page shows the above

cloister (100 feet square) at the scale of the Silchester basilica (1:600).

204. DIOSCURIDES. MATERIA MEDICA

Vienna, National Library, CODEX VINDOBONENSIS, fol. 48v

SAVIN PLANT (JUNIPERUS SABINA)

[by courtesy of the National Library of Vienna]

Pedanios Dioscurides of Anazarbos, a physician of Greek descent

who served in the army of Nero, wrote his Materia Medica around

50 A.D. It details the properties of about 600 medicinal plants and

describes animal products of dietetic and medicinal value. The writing

of Dioscurides was well known and widely read in the Middle Ages

and served as a standard text for learning in all medical schools.

The illustration shown above is from a richly (in places even

brilliantly and very realistically) illuminated copy of this treatise

executed by a Byzantine artist in 512, and now available in a

magnificent facsimile edition.

ducts, and a chimney stack for draft and evacuation of

obnoxious gas were, at the time of Louis the Pious, a

standard system used in the construction of monastic

warming rooms. Whether or not the heat produced by this

system could also be conducted into the Dormitory above

remains a moot question.

Nec ab incoepto destitit donec in circuitu oratorii refectorium hiemale et

aestivale, hypocaustorium, cellarium, domum areatum, coquinam, granarium et

dormitorum, et omnia necessaria habitacula aedificavit." (Vita S. Thiadildis

abbatissae Freckenhorsti; see Schlosser, 1896, 86, No. 283). For previous

discussions of the hypocausts of St. Gall see Keller, 1844, 21; Willis,

1848, 91; Stephani II, 1903, 77-83; Oelmann, 1923/24, 216.

Seebach, 1941, 256-73. The remains of the channels and a freestanding

chimney of the hypocaust which heated the calefactory and the

scriptorium of the Abbey of Reichenau, built at the time of Abbot Haito

(806-823), were excavated by Emil Reisser in the immediate vicinity of

the nothern transept arm of the Church of St. Mary's at Mittelzell

(see Reisser, 1960, 38ff). For other medieval calefactories with hypocausts,

see the article "Calefactorium" by Konrad Hecht in Otto

Schmidt, Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, III, 1954, cols.

308-12; and Fusch, 1910.

PURPOSE

The primary function of the calefactory, we learn from

Adalhard, was to give the monks an opportunity to warm

themselves in wintertime in the intervals between the

divine services,[63]

to hang up their clothes for drying,[64]

and

to meet at certain hours for conversation.[65]

This was also

the place, he cannot resist adding, "where the monks on

occasion succumb to drowsiness and neglect their reading

because of the pleasant warmth."[66]

It is possible, as Hafner has pointed out,[67]

that the calefactory

was also used as a general work room, where the

monks did their sewing and mending, or other domestic

chores, when the weather was not mild enough to permit

them to do this in the cloister. The calefactory may also,

during the winter or on days of inclement weather, have

been the place for the weekly washing of the feet of the

monks.[68]

To provide the wood for the hypocaust was the

responsibility of the chamberlain.[69]

Consuetudines Corbeienses; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963,

416: "Si autem hyemps fuerit et calefatiendi necessitas ingruerit, prout ei

qui praeest uisum fuerit siue ante seu post peractum officium aliquod interuallum

fiat, quando se calefacere possint." See Jones, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Et si forte quaedam ad eandem domum spetialiter pertinent

ut est de pannis infusis qui suspenduntur," and translated, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Cum . . . tam colloquendi quam coniugendi tempus licitum

aduenerit," and translated, III, 123.

Ibid., 418: "Et somnolentis et propter caloris suauitatem minus adtente

legentibus," and translated, III, 123.

See below, p. 307. According to the Usus ordinis Cistercensis the

calefactory is the place "where the brothers warm themselves, grease

their boots, and are bled; where the cantor and the scribes mix ink

and dry their parchment, and where the sacrist fetches light and glowing

cinders." See Migne, Patr. Lat., CLXVI, cols. 1387B, 1447A-C,

1466D, 1497C; and Mettler, 1909, 151.

"Ligna recipiet camerarius conventus et de illis procurabit ignemcopiosum

fratribus" (see under "camerarius" in Du Cange, Glossarium).

RECONSTRUCTION

The reconstruction of the building containing the Calefactory

and the Dormitory poses no major problems (figs.

108 and 111.B). Although no Carolingian dormitory of significance

is preserved, as far as I know, we are fairly well

informed about the materials used in their construction by

contemporary chronicles. The dormitory of Fontanella

(St.-Wandrille), completely reconstructed under Abbot

Ansegis (823-833), is a good example. The Gesta Abbatum

Fontanellensium[70]

tells us that its "walls were built in well-dressed

stone with joints or mortar made of lime and sand"

and that it received its light through "glass windows."

Apart from the walls the entire structure was built with

wood from the heart of oak, and roofed by tiles held in

place with iron nails.[71]

The layout of this dormitory

differed distinctly from the one shown on the Plan of St.

Gall, but like the dormitory of St.-Wandrille, the building

that houses the Dormitory on the Plan of St. Gall was a

masonry structure. This can be inferred from the fact that

the cloister walk with its arched openings attached to it was

unquestionably built in masonry. With its span of 40 feet

from wall to wall, this building required a roof structure

comparable to that of the adjacent church. In the latter the

tie beams of the roof must have crossed the nave in a single

span; in the dormitory—with its live load of seventy-seven

monks on the top floor—the girders that supported the

joists of the dormitory floor are likely to have found

additional support in one or two rows of free-standing

posts.[72]

SAVIN PLANT (JUNIPERUS SABINA)

205.

206.

207.

IBIZA, SPAIN

205. Erect form, sheltered habitat, 300-400 yards inland, Bay of Santa Eulalia.

This globular, symmetrical specimen reaches h. 17 feet, dia. 12-14 feet.

206. Prostrate form, exposed habitat, cliffs near Santa Eulalia. This specimen

has dia. of ca. 15 feet, h. 3-4 feet.

207. Erect specimen, umbrella-shaped crown, beach near Santa Eulalia. H. ca.

15 feet, crown dia. ca. 22 feet.

Gesta SS. Patr. Font. Coen., chap. 13(5), ed. Lohier and Laporte,

1936, 104-105: "Dormitorium fratrum . . . cuius muri de calce fortissimo

ac uiscoso arenaque rufa et fossili lapideque tofoso ac probato constructi

sunt . . . continentur in ipsa domo desuper fenestrae uitreae, cunctaque eius

fabrica, excepta maceria de materie quercuum durabilium condita est,

tegulaeque ipsius uniuersae clauis ferreis desuper affixae." See Schlosser,

1889, 30-31; Schlosser, 1896, 289, and Gesta abbatum Fontanellensium,

chap. 17; ed. Loewenfeld, Script. rer. Germ, XX, 1886, 54.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||